The Messages of Black Horror Films

In past horror films, people of color and other ethnicities were often expendable, compared with the storyâs mainstream white character. Everyone knew the black guy would die first.

The 1970s: Blacksploitation and beyond

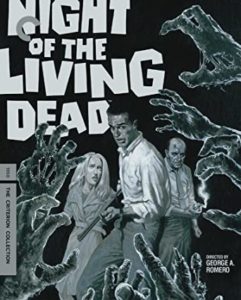

In the classic zombie film that spawned all others, Night of the Living Dead (1968), it was surprising to see the black guy survive the night fighting off our slow-moving zombies, only to get mistaken for one, killed, and burned up. I hated that ending because, on a social level, it spoke to the futility of the black fight.

In the classic zombie film that spawned all others, Night of the Living Dead (1968), it was surprising to see the black guy survive the night fighting off our slow-moving zombies, only to get mistaken for one, killed, and burned up. I hated that ending because, on a social level, it spoke to the futility of the black fight.

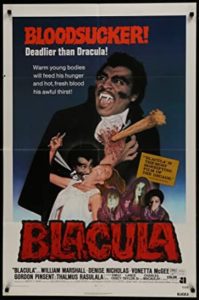

Who can forget the campy Blacula, a tale in which an African prince gets bit by Dracula himself and wakes up in 1970s L. A.?

The era of the seventies is known for its Blaxploitation1 With the advent of horror in the â70s, the black character takes something other than a subservient role to the white mainstream character. He becomes the villain to be feared but is also the anti-hero. A film of the era I remember is a movie called The Spook Who Sat by the Door. In that film, the U.S. government trains this black guy in espionage, and he uses that knowledge to fight against the government that oppresses the people.

From the 1990sâ2010s: deeper themes

In the 1990s, the anthology film, Tales from the Hood, directed by Spike Lee, had an underlying message about black-on-black crime and discrimination. Spike Lee rarely produces a movie that doesnât have a message within it. In one memorable scene, Lee uses the comparison of gangs wearing bandanas and masks with the white sheetâwearing members of the Ku Klux Klan (the KKK at the time).

An honorable mention is the movie, Bones (2001), starring hip-hop superstar Snoop Dogg. When people heard Snoop Dogg was playing this type of character, anticipation rippled among moviegoers. Plus, the outfit! I mean, if revenge looked like Snoop Dogg, then it was sweet!

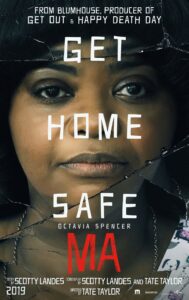

More recently, Octavia Spencer, who plays the titular character in the film Ma (2019), said she wanted to play a role that was non-traditional. In this film, however, Spencer is actually playing the traditional character. Sheâs a full-figured black woman, with a kindly exterior, taking in a bunch of kids so they can have funâbut they donât know that she has plans of revenge because what their parents did to her in high school.

I didnât enjoy the film Sweetheart that aired on Netflix. Which was a shame because the movieâs atmosphere showed a perfect blend of chilling suspense and beautiful scenery. The whole idea is perfect: youâre trapped on a deserted island, surrounded by the ocean, and plagued by a monster. But the monster concept ruined the filmâs execution. All this buildupâending with an amphibian Big Bird. Yeah. Terrifying. As Mushu says in Mulan, âI think my bunny slippers just ran for cover.”

Author Carole McDonnell pointed out to me that beneath the movieâs surface lay the message that black women often suffer in silence. We see this in the filmâs execution. For much of the movie, our main character is silent. Sheâs trying to survive with no help at all. She looks for food the best way she can. She fights the monster with what little tools she has. In the middle of the film, others from her shipwrecked party show up, including her boyfriend. They downplay her warnings about the monster and flat-out donât believe her. Even the filmâs name, Sweetheart, shows this dynamic. When sheâs trying to warn them about the monster, her boyfriend dismissively calls her âsweetheartââbefore he gets eaten.

Near the movieâs end, she decides she must take down this monster herself. She writes a note to whomever will find her record, telling them her history of not being believed. This is a nod to black women who struggle with society believing their stories.

In highlighting some of these films, I hope Iâve shown their dual purpose.

I must also mention two of my favorite vampire films that I adored watching as a child: A Vampire in Brooklyn and Blade. I loved these two films because they simply told stories about fighting evil.

In A Vampire in Brooklyn, Eddie Murphy plays a vampireâhe stepped out of his traditional roles as a comedian and became a villain. I found it odd to see him in that light, but looking back, that film showed me he wanted to take on a different role.

In Blade, Wesley Snipes plays a vampire slayer who kicks vampire tail. Thatâs all the movie was about.

What a concept! A horror movie that simply tells a story.

Horror films can explore evils worse than injustice.

I hope that in the future, we wonât need distinctions between black horror and mainstream horror because weâd all realize thereâs a greater horror out there than injustice.

See, the worst horror story isnât the one told in books or movies. Itâs the story weâre living in nowâa reality of monstrous proportions. That story has an immortal and powerful Enemy that stalks the Earth. This Enemy will use any means to destroy us. Like a violinist uses a violin, this Enemy uses the human condition as the basis for his instrument. It takes all our vices, both internal and external, and plucks them. This Enemy does not care about you. He will use anythingâlet me repeat: anythingâas a weapon to destroy us.

This horror lies inside all of us: sin.

Hereâs another reality: we can do nothing to save ourselves from him. Our pleasures, pains, hopes and dreams as  well as our good and bad intentions can all be corrupted by the Enemy. Even if you think evil doesnât exist, he uses that. Even if you think that good and evil arenât real, he uses that. Even if you think you arenât real, he uses that. Every idea, every thought, and every part of the human condition can be used by the Enemy to destroy you.

well as our good and bad intentions can all be corrupted by the Enemy. Even if you think evil doesnât exist, he uses that. Even if you think that good and evil arenât real, he uses that. Even if you think you arenât real, he uses that. Every idea, every thought, and every part of the human condition can be used by the Enemy to destroy you.

How can we resist this enemy? Iâm reminded of another horror movie, Birdbox, in which Sandra Bullock plays a woman trying to escapeâsome invisible creatures, or spirits? (I donât know, I hated that movie too.) She must row down a river blindfolded. I will spoil the movie for you because at the end, when she arrives at the place of refuge, the entities are not destroyed; theyâre only held at bay.

In our reality, this is all we can do by ourselves to resist our Enemy: hold him at bay. But eventually he will gain a foothold on us because we are too weak to fight against him by ourselves.

Black horror films can sometimes end on a dismal note. Their prevailing assumption is that the struggle will continue because the system wonât allow it to end. They present this struggle as part of the system. We can only hold it at bay.

How much more then do we fail to overcome our worst enemy with our own merits and strengths? We will fail. This Enemy, Satan, is determined that you live in separation from God.

If reality stayed that way, we would truly be living in a horror film with an enemy that no one can escape or defeat.

Thanks be to God that the horror story doesnât end on that note. Instead, Jesus Christ breaks through all the darkness with His light. He shatters the encroaching walls with the truth, slays the adversary and his minions with his sword, and ends the horror story. As Isaiah 9:2 says, âThe people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined.â

Horror films often show one person who lives to tell the tale.

In our reality, where this current horror story takes place, will that survivor be you?

What are some other black horror films I neglected to mention? What do you think about horror used as a conduit to explore social issues? How can Christians capitalize on horror as effective storytelling? Share your thoughts!

- From Wikipedia: âBlaxploitation or blacksploitation is an ethnic subgenre of the exploitation film that emerged in the United States during the early 1970s. The films, while popular, suffered backlash for disproportionate numbers of stereotypical film characters showing bad or questionable motives, including most roles as criminals resisting arrest. However, the genre does rank among the first in which black characters and communities are the heroes and subjects of film and television, rather than sidekicks, villains, or victims of brutality. The genreâs inception coincides with the rethinking of race relations in the 1970s.â ↩