What distinguishes a Christian warrior from any other kind? Is there in fact a distinctly Christian way to fight a war? Or are all war fighters basically alike? And how does the concept of being a Christian warrior affect how we read a book like Last Stands by Michael Walsh? How did the Victorian General Charles Gordon provide an example of a distinctly Christian type of warrior?

Before I answer the questions above, please allow me to indulge in mentioning that I’ve had a long career in the US Army Reserve, which has taken me to three wars (Gulf War, Iraq, Afghanistan) and plenty of non-combat military work as well, serving in Belize, Guatemala, Djibouti, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Germany, among other places. Not only do I have my own wartime and peacetime military experiences, I have met many modern warriors from a spectrum of nations and have heard in person dozens, maybe hundreds, of firsthand accounts of war. I’m also a student of history with a Masters in the subject, who has spent some time in specialized study of warfare (including here on Speculative Faith). So I feel I have some authority to talk about the nature of war, though of course people exist with even more personal experience and more personalized study than me.

Last Stands and Masculinity Defining Warriors

I recently spent a month in a training exercise at the “National Training Center” in the Mojave Desert of Fort Irwin, California. The exercise focuses on armored combat–something I’ve never done in person (I had a medical specialty during the Gulf War). Though my job as a Civil Affairs officer was to deal with role players pretending to be civilians in the battle space, we did work and move with mechanized infantry and armored formations, which again, was a new experience for me. Though the exercise kept us busy most of the time, we did have some down time, during which I read the book Last Stands by Michael Walsh.

Me “enjoying” the triple digit temps of the desert at Fort Irwin in a patch of shade under a truck.

It turns out Walsh’s book has been praised by some in politically conservative media–Walsh himself wrote an article for The American Mind–and the Epoch Times likewise sang the praises of Walsh’s book. That’s in fact why my mother bought a copy of Last Stands and sent it to me (she’s a big fan of conservative media).

Walsh looked at a number of times soldiers fought to the last man, mostly but not exclusively in Western culture, starting with the Spartans at Thermopylae and ending with US Marines in the Korean War (where Walsh’s father fought). He traced a number of common elements among these last stands. While he did mention that men fought for duty, honor, and country, to help and support one another, and at times brought up religious attitudes that under-girded decisions to fight to the last man, on multiple occasions he summarized the reasons men fight much more simply, in one word: masculinity.

War is the normal state of humankind, Walsh said. And men fight because they are men–they fight to protect their families, countries, and honor. Because, being a protector and a man of honor Walsh sees as inherently masculine things. Without such masculine virtues, civilizations are in danger of collapse, Walsh said, and so the book Last Stands is a de facto long laudatory look at the virtues of masculinity. Every battle he showcased, Walsh saw as essentially the same, though he did acknowledge some particular historical differences, basically he saw them asides to his main point. Masculinity!

Custer and His Unplanned Last Stand

Funny thing perhaps is the battles Walsh strung together I don’t see in the same light at all. For example, Custer’s Last Stand is listed among the battles, but Custer never chose to stand and fight to the last man, not really. What he chose was to move in advance of columns led by Crook, Gibbons, and Terry, to refuse Gatling guns offered by Terry, because he wanted to be highly mobile and was afraid the Sioux and Cheyenne would escape him, and also oh yes was a glory hound and didn’t want anyone else but himself to get credit for the victory he anticipated. He employed rather a rather standard attack but underestimated the numbers and determination and even the armaments of his enemies (many Indians at the Little Bighorn Battlefield had multiple-shot lever-action Winchester rifles, while the cavalrymen had single-shot rifles). He got overwhelmed and was never offered any chance to surrender. Some men under his direct command seem to have tried to escape (from where their bodies were found) but didn’t make it. 212 men dead, the end.

In other words, while Custer was not in fact a complete moron as he is sometimes portrayed, the bottom line was he made some bad decisions, employing a reasonably good tactic at most definitely the wrong place and time. He and the men under his direct command never chose to make a last stand–that’s just what happened.

I imagine a modern feminist might happily agree with Walsh that Custer was a prime specimen of masculinity, though she would probably tack on the adjective “toxic” to that description. She probably would also heartily agree with me that Custer died mostly because he made several serious tactical errors during the battle. That is, he screwed up. Because, she might say, such is the nature of toxic masculinity.

Love of Warriors: a Knee-Jerk Reaction to Feminism?

Why are political conservatives like Walsh celebrating errors like Custer’s or the Roman Varus stupidly walking into a trap at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest? Putting these failures alongside principled stands like the Spartans at Thermopylae or General Gordon’s death at Khartoum in 1885? Why?

It seems it’s a knee-jerk reaction to feminism. And other modern -isms.

Maybe with many feminists shooting rather broadly at anything even close to traditional ideas of masculinity as “toxic,” while at the same time railing against almost any version of male leadership as “patriarchy,” coupled with a sense that traditional ideas of gender are under attack via the transgender movement, it seems at least some conservatives have swallowed whole the opposite view, that all forms of masculinity were and are good. Even though some things Walsh praised were actually thick-headedness dressed up in a uniform.

Like, do we conservatives love all warriors now, as a reaction against feminists et al? Whether they were smart or dumb? Moral or immoral? Christian or not?

Um, I personally am not on board with that.

So What Kind of Warrior Isn’t Specifically Christian?

Let’s return to Custer for a minute–it’s well-established among historians that Custer planned to run for US president, probably in the year of his death (1876). As a pro-South Democrat by the way, even though he fought for the Union during the Civil War. A victory at the Little Bighorn River would have helped propel him along the way. So part of why Custer fought was his own personal ambition.

Custer also fought for his own family–a number of his family members rode with him the day he died, four brothers and a nephew. His purpose of course wasn’t to get them killed but rather to see to their advancement and personally ensure that his family members prospered.

Public Domain image of Custer

In addition, Custer wrote My Life on the Plains, a serialized set of magazine articles during his last years. The articles not only made Custer immensely popular, they earned him some good extra pay on the side. So money also motivated Custer.

We should also note Custer fought to advance the economic and political interests of the United States against Indians of the Great Plains who as a general rule were outnumbered and outgunned by the United States Army (Little Bighorn proved to be an exception to that rule). So Custer fought for his own ethnicity–his tribe as it were–against other tribes, the promotion of his people against other peoples, whether his people were right or wrong.

And even though Custer fought American Indians, most historians believe Custer kept at least one Indian woman as a personal concubine, if not more. Whether he had children by them is debated, but while Custer was fighting, he used his position as an opportunity to please himself–and maybe to increase his potential number of personal offspring.

Wait a minute, am I saying there’s anything wrong with getting paid for your work? Or with taking care of your family? Or making sure you get recognized for a good job? Because I listed those things with having concubines, which I clearly don’t approve of, so I must think these are completely bad things when talking about Custer, right?

Not exactly. Hold that thought, though.

The Selfish Gene and Being a Warrior

Infamous atheist Richard Dawkins wrote what may be his most influential book in 1976, The Selfish Gene. The book looks at human behavior from the point of view of what would genes want people to do if they had willpower. Genes of course would want to propagate themselves, so would want to have large families and as many offspring as possible.

Applied to warfare, Genghis Khan might be the ultimate model of “selfishness” as Dawkins described it. Khan conquered many nations and took as many wives and concubines among conquered peoples as he could. He had something like 40 sons, who were also prolific, to the degree that something like 16 million men today carry Genghis Khan’s Y chromosome. In terms of propagating his genes, warfare clearly worked for Khan.

If we look honestly at history, many warriors to a lesser degree than Genghis Khan were all about promoting their own personal offspring or extended network of relatives or at least their own ethnic group or tribe. Human beings really do instinctively promote their own genes by fighting for people related to them over people not related to them. Dawkins stated this sort of thing is what our genes compel us to do and is not actually virtuous, though it has historically been seen as virtue to fight for family over self.

Is that fair though? Is it inherently selfish to fight for your own family and tribe?

Modern Selfishness and Fighting For No One

The idea that taking care of your own is generally selfish isn’t just an idea from Dawkins. Jesus said that there’s no reward in heaven for loving people who already love you or greeting your own people but not others (Matthew 5:46-47). That’s not to say it’s evil to love your own family or take care of your own people. But what’s distinctive is loving people who do not already love you and greeting (and providing for) people who are not already your people. Loving your own family or people isn’t evil, but it isn’t especially good, either–everyone does that.

Except, of course, when they don’t.

Dawkins words in The Selfish Gene can be used to say people should not have families at all–doing so is inherently selfish. And people should not fight for their own people at all–again, that’s seen as indirectly selfish because your ethnic group is indirectly related to you and so helping them is to a degree helping yourself.

So wait a minute, keeping yourself provided for and no one else is not selfish?

Clearly Dawkins’s definition of selfishness is flawed. Propagation of your own genes and genes of people related to you (even if distantly) clearly isn’t the only way to be selfish. It’s also selfish in a more immediately destructive way to not provide for future generations at all and to fight for nobody.

In the name of exposing past selfishness as propagation of genes, Dawkins de facto promoted a modern kind of selfishness, where a person fights for no one except maybe self if in a dire emergency and provides for no one other than self, except maybe a non-reproductive sexual partner, if that’s not too inconvenient.

Yeah, clearly in my mind modern self-pleasure-first-selfishness exceeds the selfishness of promotion of family and tribe.

Selfish Warriors?

It bears noting that I personally have offspring and am loyal to my country and have received pay for my work and do at least of bit of making it known what kind of work I have done. Things that have motivated warriors and soldiers since the first warriors came around. I also eat when I am hungry and drink when I’m thirsty and seek shelter when I need it.

Generally taking care of yourself and others around you I would say is a normal thing to do and is good even, even if not distinctively good (the Bible makes the plain statement that not providing for your own is bad, I Timothy 5:8, in addition to commanding to care for strangers, Hebrews 13:2). It only becomes bad to provide for your own if you steal from others or hurt others to take care of yourself and your kin.

So was Custer bad? In some things he was simply a normal warrior, neither distinctively good nor bad–though he did do some bad things. He did ride out against people he believed were unable to defend themselves and took from among them those he wanted to physically please himself, literally taking for himself at least one woman who would have been the wife of another man. And he used his fame stemming from fighting Indians to promote himself at the expense of other people (he was against efforts of the Grant Administration to help black people in the South). So no, not really a good guy. Self-interested at the expense of others. Though that has been very common in the history of the world and among the long list of famous people in history, there have been many worse than Custer.

Self-Sacrifice: What Should Make Christian Warriors Distinctive

Christ’s example of self-sacrifice contrasts with Custer and many other examples of warriors serving themselves. Jesus not only washed the disciple’s feet, abandoning his rights to be served by them as their teacher, but at a more visceral level, he died on a cross for them. That abandonment of self-interest, that self-sacrifice, is what should define a Christian.

It’s of course impossible to be completely selfless. If you gave all the food you could eat to everyone who was hungry in the world, you’d die and not be able to help anyone else. That’s why the Bible standard is to love your neighbor as yourself–the presumption is that you will continue to take care of yourself, though the actual command focuses on caring for others.

That is, it isn’t wrong–it’s entirely normal–to care for yourself, but what should distinguish a Christian is not self-care but care for others. The situation where a man throws himself on a grenade to save his fellow soldier next to him–that’s the kind of behavior we should expect from warriors who march in the name of Christ.

The virtue of self-sacrifice isn’t limited to Christians, of course. The Spartans at Thermopylae believed they would die, chose to die, and did so in the defense of the rest of Greece. Not all of the virtue God put in people has been extinguished–even though a lot of it has. (Self-sacrifice on the behalf of others is rare.)

Thermopylae is opposed to Custer leading 212 soldiers to their death because of bad planning and a burning desire to be president of the United States–rather the opposite of self-sacrifice…

Killing for the Sake of Righteousness

Wait a minute–if self-sacrifice is the ultimate Christian virtue, wouldn’t it be good to refuse to fight others at all, so as to not make other people suffer? Wouldn’t that be truly selfless and self-sacrificing, even if it perhaps cost the lives of your own family, friends, tribe, and nation? Of course, this is the position of Christian pacifism. (As opposed to Utopian pacifism that believes if everyone would abandon war there would be no reason to fight and that fighting is inherently stupid–which rather unfortunately misunderstands human nature.)

As much as I admire Christian pacifism, in fact the fundamental reason to fight as a Christian warrior is not to protect self, family, friends, nation, or tribe. Although those things are very important.

The fundamental reason to fight is the one seen, though often misunderstood, in Old Testament Scripture. Joshua did not seize the Promised Land by right of might in Scripture, but by the power of God. Instead of killing every man and taking every woman and all booty for their own self-interests, at times (such as at Jericho) Israel under Joshua’s command took no treasure and no prisoners as a sign of God’s judgment on the land (a judgment prophetically foretold to Abraham in Genesis 15:16). That was very unusual in ancient warfare, taking nothing for self, killing everyone–and was also unlike the “selfishness” of battling to propagate self or similar genes as described by Richard Dawkins.

In modern times the idea that certain acts merit punishment is falling out of favor. Instead of a model of guilt and innocence, modern people tend to think of illness and wellness, seeking treatment for behavior that a modern person might prefer to call “aberrant” rather than “wrong.”

In fact, the New Testament give partial precedence for the modern view, likewise offering a cure for sin and a chance at a sort of rehabilitation–mercy over punishment. However, nowhere does the Bible step back from the idea that certain acts, such as murder of innocent people, are fundamentally wrong and deserve punishment. It simply commits to God the right to punish them (“vengeance is mine says the Lord,” Romans 12:19). Though it also admits that government may punish wrongdoing in the here-and-now (Romans 13).

There’s been a long-standing debate among Christians if we have the right to join the government in punishing evil, or for certain things we must wait divine judgment to manifest itself. Clearly I believe Christians may join the government and fight–though I nonetheless respect Christian pacifism.

Note though it’s contrary to historic Christianity to believe humanity has no evil to be punished–that God cannot and should not wage war on the evil of this world. As seen in the book of Revelation.

The Dangers of a Self-Styled Righteous Warrior, Checked by Just War Theory

So since the Christians who fight as warriors primarily fight for righteousness and not to protect–though protecting is itself righteous–what is to keep a Christian warrior from overstating what is “righteous” and going to war for any reason at all? Or to go to war for all the ancient reasons of self-gain, including spreading genetic material, but publicly and hypocritically proclaim that all was done for the sake of righteousness?

That’s almost a rhetorical question. It’s happened many times that the role of “righteous warrior” has been abused. Hernan Cortes justified destroying the Aztecs–and seizing land for himself and native mistresses in the name of righteousness. TomĂĄs de Torquemada lead the Spanish Inquisition at one point and seems to have believed he was fighting for righteousness–and he did horrific things in defense of Spanish Catholicism, killing many innocent people. Clearly it isn’t enough for a warrior or other government agent to fight for whatever cause he or she thinks is good. Going to war or engaging in an attack has to be justified by some sort of principles that assure the war is just, principles that go beyond what an individual intuits is true.

Just war theory could well be it’s own article–but in short, war is not considered viable unless performed under the auspices of legitimate authority for the purposes reducing overall suffering. A nation defending itself is the primary reason for war, but even as a war is fought, it must focus on those responsible for aggression. War should not destroy the lives of bystanders and innocent people, even though sometimes that cannot be completely avoided.

War is only righteous if done the right way, for the right reasons, protecting the innocent as much as possible, conducted not for the sake of ambition or gain, but to reduce human suffering. That’s how Christian warriors I admire have thought, checking their own ambition, fighting for the sake of others and for high ideals.

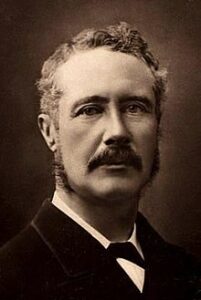

Why Was General Gordon So Great?

I wish space permitted me to discuss every aspect of Charles George Gordon’s life. He of course was in the end human, and not a perfect model in every way. But he distinguished himself as a warrior who cared about righteousness, who fought for what he believed was true, who did not ruthlessly persecute people for being different from him. In fact, he repeatedly submitted himself to people who are not from his nation or ethnicity and fought for the defense of people based on the idea it was right and just to do so–not because of personal gain, not even for gain of his nation or ethnicity.

Major General Charles Gordon. Image: Wikipedia Commons

To summarize some key aspects of Godon’s life: He was a Royal Engineer whose training included making and breaking defensive positions. He gained notoriety in the Crimean War against Russian troops for his always being willing to risk his own life in pursuit of any mission while caring for the lives of his men. At times Gordon’s superiors didn’t like him, but his subordinates followed him with great devotion, knowing his devotion to them.

Gordon became famous after he volunteered to go to China for the Second Opium War, which was over by the time he arrived. One aspect of Gordon’t life was similar to Custer–well, more than one aspect, but mainly neither of the two men liked garrison duty and enjoyed being in danger. (Which is a joy I’ve experienced myself, but can live without.)

While Gordon was in China, the Taiping Rebellion began, led by a Chinese society that halfway adopted Christianity, with a leader who claimed to be Jesus Christ’s brother and who led rebels against the Chinese government supposedly for the sake of Christ.

A man of devout though a bit eccentric Evangelical beliefs, Gordon at first empathized with the Taiping Rebellion. But when he heard of their murder of civilians, rapes, and other atrocities, his sympathies turned against them. Among a handful of European officers assigned to help the Chinese government fight the rebellion, Gordon wound up in command of a Chinese army.

He trained his troops so well that they never lost any battles, proving to be key in defeating the Taiping Rebellion. Gordon never hesitated to respect Chinese customs and wore Chinese clothing (though he never mastered speaking Chinese) but at the same time honestly clashed with both Chinese and European superiors when he felt they were making mistakes. He never seemed racist and the Mandarins appreciated that about him, even though at times he offended them, as in one incident he looked up the word “imbecile” in a Chinese dictionary to let leaders know what he thought of their strategy at the time.

Chinese Mandarins of the period often engaged in corruption for their own personal profit, a practice even Europeans in China followed as well–except Gordon, who returned money sent to him in excess of his minimal needs. In spite of clashing with Chinese authorities at times, they found Gordon to be a thoroughly honest and decent man. When his time of service in China was over, the Mandarins offered to hire him to keep them in their service.

Gordon, after a brief return to England where he contributed to local charities, next served in Africa, at the time when the British were in cooperation with the Ottoman Empire. He received the title “Pasha” or “ruler” and wore Ottoman clothes and communicated in broken Arabic and showed himself in many ways free from the racism common in his day. Posted in Sudan, he fought for the elimination of the African slave trade in his region.

He again proved personally incorruptible but found himself surrounded by people taking bribes who undermined his efforts to suppress the slave trade in Sudan. So he produced little long-term effect. Gordon suffered a breakdown in morale after this realization and returned to England.

Gordon received many offers to serve with many countries in colonial ventures in Africa. He was quite well-known and admired for his ability to work with foreigners, though he felt discouraged about his own efforts to stamp out the slave trade in Sudan.

A messianic figure arose among the Arabs in Sudan, a man who claimed to be the Mahdi, in effect the second coming of Muhammad. This man, Muhammad Ahmad, intended to ride to the destruction of all of British Africa if he could. Gordon managed to get himself posted back in Khartoum, capital of Sudan. His superiors believed he was going to rescue a key group of officials, but Gordon decided to defend the black African Sudanese against the Arab Muslims who wanted to kill them (a conflict that would re-appear in the split between Sudan and South Sudan in the 21st Century).

Gordon fortified the city against the attackers threatening them and promised to hold out until the British sent a relief force.

The frank expression of opinions Gordon engaged in with the press infuriated the British government. Gordon also seemed unstable to many people and while he had admirers, he also had political enemies. So while the government did sent a relief force, they sent a small one, moving slowly.

Khartoum under Gordon’s command held out against Muhammad Ahmad’s army for a year before falling to an attack. Gordon died firing his revolver at enemies.

While it’s true Gordon hoped the British government would rescue him and the people under his command, he declared multiple times he would rather die defending the people of Sudan than surrender. The vanguard of the British relief force arrived two days after his death.

Criticism of Gordon

The report of Gordon’s death shocked the British public in a way similar to how Americans reacted to Custer’s death. Eventually the British response defeated those responsible for killing Gordon, though in fact the problems in Sudan persist until this day. However, unlike Custer who was not criticized until the 1930s, some people immediately criticized Gordon. Including his own government.

One critic from his own time claimed Gordon was frequently drunk–something no one else ever corroborated. Likewise a Twentieth Century writer claimed Gordon was a homosexual. Well, he never married and had no children, but in the Victorian Era that wasn’t considered as unusual as now. There is also a journal entry from when he was 14 and in boarding school stating that he wished he were a eunuch–which someone has conflated to him having some sort of homosexual experience. It could just as well have been he was ashamed of heterosexual desire or masturbation–the evidence he was gay is paper-thin. And no one has ever corroborated that Gordon ever had sex with anyone, ever, let alone gay sex. If he was homosexual, it seems he was utterly celibate.

From a modern point of view someone who never had sex seems a bizarre creature indeed. Certainly I don’t believe that not having sex is in itself a virtue. Still, I would not criticize Gordon for that. It was his legitimate choice to make (Matthew 19:12, I Cor 7:8).

Many modern critics speak of Gordon’s death wish or his extreme religiosity as a handicap. He probably would also be criticized for having a “white savior” complex. But Gordon was tolerant of other Christian denominations, including Catholics, in a period when such tolerance was uncommon. He worked with ethnic groups other than his own without pandering to them or selling them out. He also fought against both a fanatical version of Christianity and Islamic fanaticism, without ever justifying in his own mind any need to the commit atrocities they did.

Conclusion

In a world where warriors of every nation fight for their own family and tribe, where assuring personal prosperity and advancement is common, when waging war to take what others have and cannot defend is common, where spreading one’s own genetic inheritance as much as possible in the wake of war has happened often enough, the Christian idea of warfare is uncommon. Warriors who live the Christian ideal are rarer still.

Charles Gordon was in many ways eccentric and could have used some greater wisdom in some of the things he said that may have angered superiors for no good reason. Perhaps he did have a sort of death wish and his greatest tragedy was his closest followers in Khartoum, who had believed in him, were slaughtered after his death.

But he fought for righteousness, against evil, never for pride as far as what history records of him, for people he had no reason to help other than he believed it was the right thing to do. He was always honest (maybe too blunt at times), always incorruptible, courageous, and faithful to end, choosing to die for the sake of self-sacrifice. Not stumbling into his death foolishly, like Custer.

Was Gordon a symbol of masculinity? For Michael Walsh that’s an important question. For me, it’s not. Gordon was a Christian warrior, the closest to true to type as we are likely to ever see. It would be good to see more people like him–in both fact and fiction.

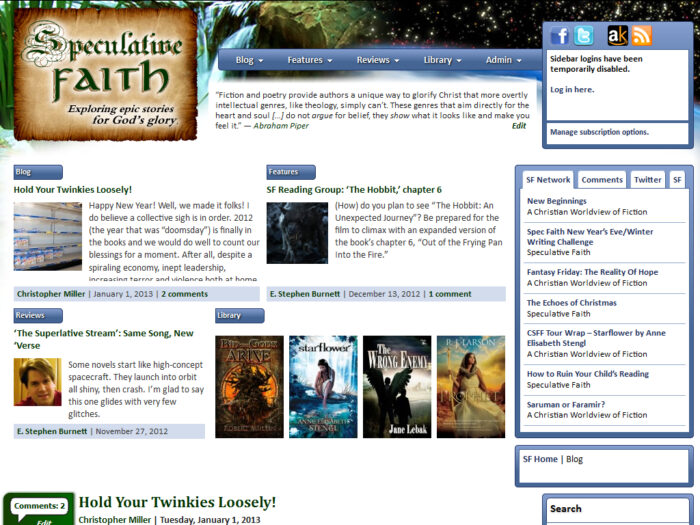

So culture changes, and with it, the stories we write, including the stories Christians write about life as or for or about Christians. Anyone reading articles archived here at Spec Faith on this topic will know that as a group we do not believe every story labeled “Christian fiction” needs to be evangelistic, with a character or two converting to Christianity. But the stories that do present the gospel, do need to reflect the truth at some level, and not error.

So culture changes, and with it, the stories we write, including the stories Christians write about life as or for or about Christians. Anyone reading articles archived here at Spec Faith on this topic will know that as a group we do not believe every story labeled “Christian fiction” needs to be evangelistic, with a character or two converting to Christianity. But the stories that do present the gospel, do need to reflect the truth at some level, and not error.

I’ve read other books with a similar concept, but I wonder now if such stories that tinker with gender roles will survive. Or how about movies like Some Like It Hot (1959 with Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, Jack Lemon) or Tootsie (1984 with Dustin Hoffman and Jessica Lange)? Are these stories destined to be banned one day, to be looked at as threatening in the same way as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has become in the arena of race?

I’ve read other books with a similar concept, but I wonder now if such stories that tinker with gender roles will survive. Or how about movies like Some Like It Hot (1959 with Marilyn Monroe, Tony Curtis, Jack Lemon) or Tootsie (1984 with Dustin Hoffman and Jessica Lange)? Are these stories destined to be banned one day, to be looked at as threatening in the same way as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has become in the arena of race?

Earthâs crust to access geothermal energy and release a crack that travels around the world. After the experiment succeeds, one scene shows all the animals running away. It made me laugh. (âStupid humans,â you could hear the animals say.) This movie obviously showed how manâs consistent need to manipulate nature points to his own self-destruction.

Earthâs crust to access geothermal energy and release a crack that travels around the world. After the experiment succeeds, one scene shows all the animals running away. It made me laugh. (âStupid humans,â you could hear the animals say.) This movie obviously showed how manâs consistent need to manipulate nature points to his own self-destruction.

separating true believers from the damned. It involves a complex aligning of geopolitical events to bring about the end in which the Rapture will occur, the reign of the Antichrist, then a global war between Satan and his demonic forces and Godâwho will ultimately win. The judgment ends by the purification of fire.

separating true believers from the damned. It involves a complex aligning of geopolitical events to bring about the end in which the Rapture will occur, the reign of the Antichrist, then a global war between Satan and his demonic forces and Godâwho will ultimately win. The judgment ends by the purification of fire.

Clearly, Hunger is the Part 2 of this two-book explanation for the existence of the world a reader will discover in the Safe Lands trilogy. For those who have not read the Part 1—Thirst—I strongly encourage you to start there. The really good news is that the book is available on Kindle for $2.99. That’s a steal. This book is fast-paced and highly entertaining. No one should worry that they will arrive at a cliffhanger ending, though it’s evident at the conclusion of Thirst that there needs to be more story. (See

Clearly, Hunger is the Part 2 of this two-book explanation for the existence of the world a reader will discover in the Safe Lands trilogy. For those who have not read the Part 1—Thirst—I strongly encourage you to start there. The really good news is that the book is available on Kindle for $2.99. That’s a steal. This book is fast-paced and highly entertaining. No one should worry that they will arrive at a cliffhanger ending, though it’s evident at the conclusion of Thirst that there needs to be more story. (See