Last Stands, Custer, General Gordon, and Being a Christian Warrior

What distinguishes a Christian warrior from any other kind? Is there in fact a distinctly Christian way to fight a war? Or are all war fighters basically alike? And how does the concept of being a Christian warrior affect how we read a book like Last Stands by Michael Walsh? How did the Victorian General Charles Gordon provide an example of a distinctly Christian type of warrior?

Before I answer the questions above, please allow me to indulge in mentioning that I’ve had a long career in the US Army Reserve, which has taken me to three wars (Gulf War, Iraq, Afghanistan) and plenty of non-combat military work as well, serving in Belize, Guatemala, Djibouti, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Germany, among other places. Not only do I have my own wartime and peacetime military experiences, I have met many modern warriors from a spectrum of nations and have heard in person dozens, maybe hundreds, of firsthand accounts of war. I’m also a student of history with a Masters in the subject, who has spent some time in specialized study of warfare (including here on Speculative Faith). So I feel I have some authority to talk about the nature of war, though of course people exist with even more personal experience and more personalized study than me.

Last Stands and Masculinity Defining Warriors

I recently spent a month in a training exercise at the “National Training Center” in the Mojave Desert of Fort Irwin, California. The exercise focuses on armored combat–something I’ve never done in person (I had a medical specialty during the Gulf War). Though my job as a Civil Affairs officer was to deal with role players pretending to be civilians in the battle space, we did work and move with mechanized infantry and armored formations, which again, was a new experience for me. Though the exercise kept us busy most of the time, we did have some down time, during which I read the book Last Stands by Michael Walsh.

Me “enjoying” the triple digit temps of the desert at Fort Irwin in a patch of shade under a truck.

It turns out Walsh’s book has been praised by some in politically conservative media–Walsh himself wrote an article for The American Mind–and the Epoch Times likewise sang the praises of Walsh’s book. That’s in fact why my mother bought a copy of Last Stands and sent it to me (she’s a big fan of conservative media).

Walsh looked at a number of times soldiers fought to the last man, mostly but not exclusively in Western culture, starting with the Spartans at Thermopylae and ending with US Marines in the Korean War (where Walsh’s father fought). He traced a number of common elements among these last stands. While he did mention that men fought for duty, honor, and country, to help and support one another, and at times brought up religious attitudes that under-girded decisions to fight to the last man, on multiple occasions he summarized the reasons men fight much more simply, in one word: masculinity.

War is the normal state of humankind, Walsh said. And men fight because they are men–they fight to protect their families, countries, and honor. Because, being a protector and a man of honor Walsh sees as inherently masculine things. Without such masculine virtues, civilizations are in danger of collapse, Walsh said, and so the book Last Stands is a de facto long laudatory look at the virtues of masculinity. Every battle he showcased, Walsh saw as essentially the same, though he did acknowledge some particular historical differences, basically he saw them asides to his main point. Masculinity!

Custer and His Unplanned Last Stand

Funny thing perhaps is the battles Walsh strung together I don’t see in the same light at all. For example, Custer’s Last Stand is listed among the battles, but Custer never chose to stand and fight to the last man, not really. What he chose was to move in advance of columns led by Crook, Gibbons, and Terry, to refuse Gatling guns offered by Terry, because he wanted to be highly mobile and was afraid the Sioux and Cheyenne would escape him, and also oh yes was a glory hound and didn’t want anyone else but himself to get credit for the victory he anticipated. He employed rather a rather standard attack but underestimated the numbers and determination and even the armaments of his enemies (many Indians at the Little Bighorn Battlefield had multiple-shot lever-action Winchester rifles, while the cavalrymen had single-shot rifles). He got overwhelmed and was never offered any chance to surrender. Some men under his direct command seem to have tried to escape (from where their bodies were found) but didn’t make it. 212 men dead, the end.

In other words, while Custer was not in fact a complete moron as he is sometimes portrayed, the bottom line was he made some bad decisions, employing a reasonably good tactic at most definitely the wrong place and time. He and the men under his direct command never chose to make a last stand–that’s just what happened.

I imagine a modern feminist might happily agree with Walsh that Custer was a prime specimen of masculinity, though she would probably tack on the adjective “toxic” to that description. She probably would also heartily agree with me that Custer died mostly because he made several serious tactical errors during the battle. That is, he screwed up. Because, she might say, such is the nature of toxic masculinity.

Love of Warriors: a Knee-Jerk Reaction to Feminism?

Why are political conservatives like Walsh celebrating errors like Custer’s or the Roman Varus stupidly walking into a trap at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest? Putting these failures alongside principled stands like the Spartans at Thermopylae or General Gordon’s death at Khartoum in 1885? Why?

It seems it’s a knee-jerk reaction to feminism. And other modern -isms.

Maybe with many feminists shooting rather broadly at anything even close to traditional ideas of masculinity as “toxic,” while at the same time railing against almost any version of male leadership as “patriarchy,” coupled with a sense that traditional ideas of gender are under attack via the transgender movement, it seems at least some conservatives have swallowed whole the opposite view, that all forms of masculinity were and are good. Even though some things Walsh praised were actually thick-headedness dressed up in a uniform.

Like, do we conservatives love all warriors now, as a reaction against feminists et al? Whether they were smart or dumb? Moral or immoral? Christian or not?

Um, I personally am not on board with that.

So What Kind of Warrior Isn’t Specifically Christian?

Let’s return to Custer for a minute–it’s well-established among historians that Custer planned to run for US president, probably in the year of his death (1876). As a pro-South Democrat by the way, even though he fought for the Union during the Civil War. A victory at the Little Bighorn River would have helped propel him along the way. So part of why Custer fought was his own personal ambition.

Custer also fought for his own family–a number of his family members rode with him the day he died, four brothers and a nephew. His purpose of course wasn’t to get them killed but rather to see to their advancement and personally ensure that his family members prospered.

Public Domain image of Custer

In addition, Custer wrote My Life on the Plains, a serialized set of magazine articles during his last years. The articles not only made Custer immensely popular, they earned him some good extra pay on the side. So money also motivated Custer.

We should also note Custer fought to advance the economic and political interests of the United States against Indians of the Great Plains who as a general rule were outnumbered and outgunned by the United States Army (Little Bighorn proved to be an exception to that rule). So Custer fought for his own ethnicity–his tribe as it were–against other tribes, the promotion of his people against other peoples, whether his people were right or wrong.

And even though Custer fought American Indians, most historians believe Custer kept at least one Indian woman as a personal concubine, if not more. Whether he had children by them is debated, but while Custer was fighting, he used his position as an opportunity to please himself–and maybe to increase his potential number of personal offspring.

Wait a minute, am I saying there’s anything wrong with getting paid for your work? Or with taking care of your family? Or making sure you get recognized for a good job? Because I listed those things with having concubines, which I clearly don’t approve of, so I must think these are completely bad things when talking about Custer, right?

Not exactly. Hold that thought, though.

The Selfish Gene and Being a Warrior

Infamous atheist Richard Dawkins wrote what may be his most influential book in 1976, The Selfish Gene. The book looks at human behavior from the point of view of what would genes want people to do if they had willpower. Genes of course would want to propagate themselves, so would want to have large families and as many offspring as possible.

Applied to warfare, Genghis Khan might be the ultimate model of “selfishness” as Dawkins described it. Khan conquered many nations and took as many wives and concubines among conquered peoples as he could. He had something like 40 sons, who were also prolific, to the degree that something like 16 million men today carry Genghis Khan’s Y chromosome. In terms of propagating his genes, warfare clearly worked for Khan.

If we look honestly at history, many warriors to a lesser degree than Genghis Khan were all about promoting their own personal offspring or extended network of relatives or at least their own ethnic group or tribe. Human beings really do instinctively promote their own genes by fighting for people related to them over people not related to them. Dawkins stated this sort of thing is what our genes compel us to do and is not actually virtuous, though it has historically been seen as virtue to fight for family over self.

Is that fair though? Is it inherently selfish to fight for your own family and tribe?

Modern Selfishness and Fighting For No One

The idea that taking care of your own is generally selfish isn’t just an idea from Dawkins. Jesus said that there’s no reward in heaven for loving people who already love you or greeting your own people but not others (Matthew 5:46-47). That’s not to say it’s evil to love your own family or take care of your own people. But what’s distinctive is loving people who do not already love you and greeting (and providing for) people who are not already your people. Loving your own family or people isn’t evil, but it isn’t especially good, either–everyone does that.

Except, of course, when they don’t.

Dawkins words in The Selfish Gene can be used to say people should not have families at all–doing so is inherently selfish. And people should not fight for their own people at all–again, that’s seen as indirectly selfish because your ethnic group is indirectly related to you and so helping them is to a degree helping yourself.

So wait a minute, keeping yourself provided for and no one else is not selfish?

Clearly Dawkins’s definition of selfishness is flawed. Propagation of your own genes and genes of people related to you (even if distantly) clearly isn’t the only way to be selfish. It’s also selfish in a more immediately destructive way to not provide for future generations at all and to fight for nobody.

In the name of exposing past selfishness as propagation of genes, Dawkins de facto promoted a modern kind of selfishness, where a person fights for no one except maybe self if in a dire emergency and provides for no one other than self, except maybe a non-reproductive sexual partner, if that’s not too inconvenient.

Yeah, clearly in my mind modern self-pleasure-first-selfishness exceeds the selfishness of promotion of family and tribe.

Selfish Warriors?

It bears noting that I personally have offspring and am loyal to my country and have received pay for my work and do at least of bit of making it known what kind of work I have done. Things that have motivated warriors and soldiers since the first warriors came around. I also eat when I am hungry and drink when I’m thirsty and seek shelter when I need it.

Generally taking care of yourself and others around you I would say is a normal thing to do and is good even, even if not distinctively good (the Bible makes the plain statement that not providing for your own is bad, I Timothy 5:8, in addition to commanding to care for strangers, Hebrews 13:2). It only becomes bad to provide for your own if you steal from others or hurt others to take care of yourself and your kin.

So was Custer bad? In some things he was simply a normal warrior, neither distinctively good nor bad–though he did do some bad things. He did ride out against people he believed were unable to defend themselves and took from among them those he wanted to physically please himself, literally taking for himself at least one woman who would have been the wife of another man. And he used his fame stemming from fighting Indians to promote himself at the expense of other people (he was against efforts of the Grant Administration to help black people in the South). So no, not really a good guy. Self-interested at the expense of others. Though that has been very common in the history of the world and among the long list of famous people in history, there have been many worse than Custer.

Self-Sacrifice: What Should Make Christian Warriors Distinctive

Christ’s example of self-sacrifice contrasts with Custer and many other examples of warriors serving themselves. Jesus not only washed the disciple’s feet, abandoning his rights to be served by them as their teacher, but at a more visceral level, he died on a cross for them. That abandonment of self-interest, that self-sacrifice, is what should define a Christian.

It’s of course impossible to be completely selfless. If you gave all the food you could eat to everyone who was hungry in the world, you’d die and not be able to help anyone else. That’s why the Bible standard is to love your neighbor as yourself–the presumption is that you will continue to take care of yourself, though the actual command focuses on caring for others.

That is, it isn’t wrong–it’s entirely normal–to care for yourself, but what should distinguish a Christian is not self-care but care for others. The situation where a man throws himself on a grenade to save his fellow soldier next to him–that’s the kind of behavior we should expect from warriors who march in the name of Christ.

The virtue of self-sacrifice isn’t limited to Christians, of course. The Spartans at Thermopylae believed they would die, chose to die, and did so in the defense of the rest of Greece. Not all of the virtue God put in people has been extinguished–even though a lot of it has. (Self-sacrifice on the behalf of others is rare.)

Thermopylae is opposed to Custer leading 212 soldiers to their death because of bad planning and a burning desire to be president of the United States–rather the opposite of self-sacrifice…

Killing for the Sake of Righteousness

Wait a minute–if self-sacrifice is the ultimate Christian virtue, wouldn’t it be good to refuse to fight others at all, so as to not make other people suffer? Wouldn’t that be truly selfless and self-sacrificing, even if it perhaps cost the lives of your own family, friends, tribe, and nation? Of course, this is the position of Christian pacifism. (As opposed to Utopian pacifism that believes if everyone would abandon war there would be no reason to fight and that fighting is inherently stupid–which rather unfortunately misunderstands human nature.)

As much as I admire Christian pacifism, in fact the fundamental reason to fight as a Christian warrior is not to protect self, family, friends, nation, or tribe. Although those things are very important.

The fundamental reason to fight is the one seen, though often misunderstood, in Old Testament Scripture. Joshua did not seize the Promised Land by right of might in Scripture, but by the power of God. Instead of killing every man and taking every woman and all booty for their own self-interests, at times (such as at Jericho) Israel under Joshua’s command took no treasure and no prisoners as a sign of God’s judgment on the land (a judgment prophetically foretold to Abraham in Genesis 15:16). That was very unusual in ancient warfare, taking nothing for self, killing everyone–and was also unlike the “selfishness” of battling to propagate self or similar genes as described by Richard Dawkins.

In modern times the idea that certain acts merit punishment is falling out of favor. Instead of a model of guilt and innocence, modern people tend to think of illness and wellness, seeking treatment for behavior that a modern person might prefer to call “aberrant” rather than “wrong.”

In fact, the New Testament give partial precedence for the modern view, likewise offering a cure for sin and a chance at a sort of rehabilitation–mercy over punishment. However, nowhere does the Bible step back from the idea that certain acts, such as murder of innocent people, are fundamentally wrong and deserve punishment. It simply commits to God the right to punish them (“vengeance is mine says the Lord,” Romans 12:19). Though it also admits that government may punish wrongdoing in the here-and-now (Romans 13).

There’s been a long-standing debate among Christians if we have the right to join the government in punishing evil, or for certain things we must wait divine judgment to manifest itself. Clearly I believe Christians may join the government and fight–though I nonetheless respect Christian pacifism.

Note though it’s contrary to historic Christianity to believe humanity has no evil to be punished–that God cannot and should not wage war on the evil of this world. As seen in the book of Revelation.

The Dangers of a Self-Styled Righteous Warrior, Checked by Just War Theory

So since the Christians who fight as warriors primarily fight for righteousness and not to protect–though protecting is itself righteous–what is to keep a Christian warrior from overstating what is “righteous” and going to war for any reason at all? Or to go to war for all the ancient reasons of self-gain, including spreading genetic material, but publicly and hypocritically proclaim that all was done for the sake of righteousness?

That’s almost a rhetorical question. It’s happened many times that the role of “righteous warrior” has been abused. Hernan Cortes justified destroying the Aztecs–and seizing land for himself and native mistresses in the name of righteousness. Tomás de Torquemada lead the Spanish Inquisition at one point and seems to have believed he was fighting for righteousness–and he did horrific things in defense of Spanish Catholicism, killing many innocent people. Clearly it isn’t enough for a warrior or other government agent to fight for whatever cause he or she thinks is good. Going to war or engaging in an attack has to be justified by some sort of principles that assure the war is just, principles that go beyond what an individual intuits is true.

Just war theory could well be it’s own article–but in short, war is not considered viable unless performed under the auspices of legitimate authority for the purposes reducing overall suffering. A nation defending itself is the primary reason for war, but even as a war is fought, it must focus on those responsible for aggression. War should not destroy the lives of bystanders and innocent people, even though sometimes that cannot be completely avoided.

War is only righteous if done the right way, for the right reasons, protecting the innocent as much as possible, conducted not for the sake of ambition or gain, but to reduce human suffering. That’s how Christian warriors I admire have thought, checking their own ambition, fighting for the sake of others and for high ideals.

Why Was General Gordon So Great?

I wish space permitted me to discuss every aspect of Charles George Gordon’s life. He of course was in the end human, and not a perfect model in every way. But he distinguished himself as a warrior who cared about righteousness, who fought for what he believed was true, who did not ruthlessly persecute people for being different from him. In fact, he repeatedly submitted himself to people who are not from his nation or ethnicity and fought for the defense of people based on the idea it was right and just to do so–not because of personal gain, not even for gain of his nation or ethnicity.

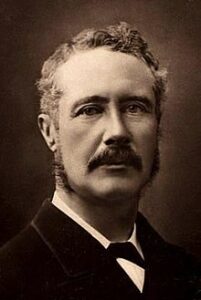

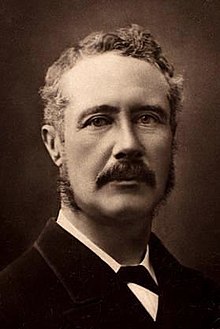

Major General Charles Gordon. Image: Wikipedia Commons

To summarize some key aspects of Godon’s life: He was a Royal Engineer whose training included making and breaking defensive positions. He gained notoriety in the Crimean War against Russian troops for his always being willing to risk his own life in pursuit of any mission while caring for the lives of his men. At times Gordon’s superiors didn’t like him, but his subordinates followed him with great devotion, knowing his devotion to them.

Gordon became famous after he volunteered to go to China for the Second Opium War, which was over by the time he arrived. One aspect of Gordon’t life was similar to Custer–well, more than one aspect, but mainly neither of the two men liked garrison duty and enjoyed being in danger. (Which is a joy I’ve experienced myself, but can live without.)

While Gordon was in China, the Taiping Rebellion began, led by a Chinese society that halfway adopted Christianity, with a leader who claimed to be Jesus Christ’s brother and who led rebels against the Chinese government supposedly for the sake of Christ.

A man of devout though a bit eccentric Evangelical beliefs, Gordon at first empathized with the Taiping Rebellion. But when he heard of their murder of civilians, rapes, and other atrocities, his sympathies turned against them. Among a handful of European officers assigned to help the Chinese government fight the rebellion, Gordon wound up in command of a Chinese army.

He trained his troops so well that they never lost any battles, proving to be key in defeating the Taiping Rebellion. Gordon never hesitated to respect Chinese customs and wore Chinese clothing (though he never mastered speaking Chinese) but at the same time honestly clashed with both Chinese and European superiors when he felt they were making mistakes. He never seemed racist and the Mandarins appreciated that about him, even though at times he offended them, as in one incident he looked up the word “imbecile” in a Chinese dictionary to let leaders know what he thought of their strategy at the time.

Chinese Mandarins of the period often engaged in corruption for their own personal profit, a practice even Europeans in China followed as well–except Gordon, who returned money sent to him in excess of his minimal needs. In spite of clashing with Chinese authorities at times, they found Gordon to be a thoroughly honest and decent man. When his time of service in China was over, the Mandarins offered to hire him to keep them in their service.

Gordon, after a brief return to England where he contributed to local charities, next served in Africa, at the time when the British were in cooperation with the Ottoman Empire. He received the title “Pasha” or “ruler” and wore Ottoman clothes and communicated in broken Arabic and showed himself in many ways free from the racism common in his day. Posted in Sudan, he fought for the elimination of the African slave trade in his region.

He again proved personally incorruptible but found himself surrounded by people taking bribes who undermined his efforts to suppress the slave trade in Sudan. So he produced little long-term effect. Gordon suffered a breakdown in morale after this realization and returned to England.

Gordon received many offers to serve with many countries in colonial ventures in Africa. He was quite well-known and admired for his ability to work with foreigners, though he felt discouraged about his own efforts to stamp out the slave trade in Sudan.

A messianic figure arose among the Arabs in Sudan, a man who claimed to be the Mahdi, in effect the second coming of Muhammad. This man, Muhammad Ahmad, intended to ride to the destruction of all of British Africa if he could. Gordon managed to get himself posted back in Khartoum, capital of Sudan. His superiors believed he was going to rescue a key group of officials, but Gordon decided to defend the black African Sudanese against the Arab Muslims who wanted to kill them (a conflict that would re-appear in the split between Sudan and South Sudan in the 21st Century).

Gordon fortified the city against the attackers threatening them and promised to hold out until the British sent a relief force.

The frank expression of opinions Gordon engaged in with the press infuriated the British government. Gordon also seemed unstable to many people and while he had admirers, he also had political enemies. So while the government did sent a relief force, they sent a small one, moving slowly.

Khartoum under Gordon’s command held out against Muhammad Ahmad’s army for a year before falling to an attack. Gordon died firing his revolver at enemies.

While it’s true Gordon hoped the British government would rescue him and the people under his command, he declared multiple times he would rather die defending the people of Sudan than surrender. The vanguard of the British relief force arrived two days after his death.

Criticism of Gordon

The report of Gordon’s death shocked the British public in a way similar to how Americans reacted to Custer’s death. Eventually the British response defeated those responsible for killing Gordon, though in fact the problems in Sudan persist until this day. However, unlike Custer who was not criticized until the 1930s, some people immediately criticized Gordon. Including his own government.

One critic from his own time claimed Gordon was frequently drunk–something no one else ever corroborated. Likewise a Twentieth Century writer claimed Gordon was a homosexual. Well, he never married and had no children, but in the Victorian Era that wasn’t considered as unusual as now. There is also a journal entry from when he was 14 and in boarding school stating that he wished he were a eunuch–which someone has conflated to him having some sort of homosexual experience. It could just as well have been he was ashamed of heterosexual desire or masturbation–the evidence he was gay is paper-thin. And no one has ever corroborated that Gordon ever had sex with anyone, ever, let alone gay sex. If he was homosexual, it seems he was utterly celibate.

From a modern point of view someone who never had sex seems a bizarre creature indeed. Certainly I don’t believe that not having sex is in itself a virtue. Still, I would not criticize Gordon for that. It was his legitimate choice to make (Matthew 19:12, I Cor 7:8).

Many modern critics speak of Gordon’s death wish or his extreme religiosity as a handicap. He probably would also be criticized for having a “white savior” complex. But Gordon was tolerant of other Christian denominations, including Catholics, in a period when such tolerance was uncommon. He worked with ethnic groups other than his own without pandering to them or selling them out. He also fought against both a fanatical version of Christianity and Islamic fanaticism, without ever justifying in his own mind any need to the commit atrocities they did.

Conclusion

In a world where warriors of every nation fight for their own family and tribe, where assuring personal prosperity and advancement is common, when waging war to take what others have and cannot defend is common, where spreading one’s own genetic inheritance as much as possible in the wake of war has happened often enough, the Christian idea of warfare is uncommon. Warriors who live the Christian ideal are rarer still.

Charles Gordon was in many ways eccentric and could have used some greater wisdom in some of the things he said that may have angered superiors for no good reason. Perhaps he did have a sort of death wish and his greatest tragedy was his closest followers in Khartoum, who had believed in him, were slaughtered after his death.

But he fought for righteousness, against evil, never for pride as far as what history records of him, for people he had no reason to help other than he believed it was the right thing to do. He was always honest (maybe too blunt at times), always incorruptible, courageous, and faithful to end, choosing to die for the sake of self-sacrifice. Not stumbling into his death foolishly, like Custer.

Was Gordon a symbol of masculinity? For Michael Walsh that’s an important question. For me, it’s not. Gordon was a Christian warrior, the closest to true to type as we are likely to ever see. It would be good to see more people like him–in both fact and fiction.

Welp, you mentioned the concept of toxic masculinity, so I won’t feel obligated to hash it out, unless someone wants to go at the particular angle of why violence would be a masculine “virtue,” if we deconstructed what was meant by “virtue.”

But as counterpoint to Dawkins, a lot of the more current anthropological/sociological interest is in cooperation (maybe with some points of selfishness as compare-contrast). Because humans are pretty weak and horribly slow. All the apes could tear our faces off, and most four-footed animals can absolutely outrun us (tho we apparently have bonkers crazy stamina and can run down our prey to exhaustion).

As a species we dumped the majority of our stat points into cooperation. It could be that we developed our bigger brains and greater intelligence in order to better manage our relationships within our tribes, and thus leverage more cooperative benefits. Even tool-making, if you want to get more complicated than maybe a hammer-stone, requires a lot of teaching — which is a cooperative activity.

That’s a theory why humans are one of the few species who go through menopause — that helping to raise grandchildren increases the overall survival odds rather than birthing more children to compete for resources with your grandchildren. It’s actually pretty unusual for a single nuclear family to raise its children alone: the whole “takes a village” trope was the norm for centuries and millennia. And communal child-raising seems to correlate with better survival odds. Meerkats apparently synchronize their births and all the mothers nurse whichever pups need nursing. Communal kitten-raising is pretty normal for colonies of related female cats.

But getting back to the whole war thing — and obviously I’m simplifying everything for convenience’s sake — it could be argued that no one in America has fought an actual war for country and family since maybe 1812, with an exception for the Pacific Theater in WWII. And I’m kinda on the fence in general about WWI and the rest of WWII — we were doing cooperative stuff with our allies, but it was hardly disinterested. This is where I wax on about the difference between individual versus systemic stuff. All the Indian wars were straight-up colonialism and exploitation, seeing as how we broke pretty much every treaty we made. Even with incompatible ideas and cultures about warfare between the whites and the natives, who knows how much war and death could have been minimized if white people had just stayed in their lanes.

Tho that was one of the reasons the colonists fought for independence from Britain, because Britain was intending to honor their treaties (at the moment, at least) with the natives and not allow white expansion into/past the Appalachians, which pissed off the colonists who wanted more land and resources to exploit. (Granted, I’m using a very broad definition of “exploitation” that pretty much includes all industrialization, because give me a reason why it’s not.)

Travis, I would argue most of your tours were more about maintaining America’s system of exploiting the oilfields of the Middle East (however indirect they are, through the Saudis and whatnot) and whatever weird, backhanded colonialism we have been/are still doing in Afghanistan. If it makes you feel better, America’s not the only one at fault (coughRussiacough, but they are doing much the same thing for much the same reasons). (grumblegrumble Afghanistan was doing just fine in the sixties grumble)

Likewise, Gordon, no matter how good/okay he was as a person (there seems to be enough evidence to conclude he was at least asexual, which would have been iffy enough in Victorian culture, but I don’t see there being sufficient reason to exclude homosexuality yet), was also working for the systemic British exploitation of China and the Middle East-North Africa, though maybe not Crimea, but I would actually have to find out what the heck the Crimean war was about since the top paragraph of the Wiki page doesn’t help.

TL;DR: I can find the idea of violence in defense of people okay, sure, but I don’t actually think most wars past 1700 or so — besides civil wars and some exceptions like some sections of WWI or WWII — were actually about defending any people or families or ways of life, but about empiric power-grabs and economic bullhonk. And there was plenty of empiric bullhonk before 1700, too.

As far as what the very latest views of human nature are via science, I am not completely current on this debate. I know Dawkins’s ideas remain popular. I know that the debate about the nature of warfare and when it began runs deep. I think the idea that humans were basically cooperative and developed warfare after the invention of agriculture is a feminist darling that in fact isn’t held by most anthropologists. The evidence for humans killing humans is very ancient. However, I’m a (low-level) historian and not an anthropologist–maybe the “humans are cooperative” mode of thought is currently ascendant. I’m not sure.

I also know a single human with a spear can kill one of the most fearsome predators around–the Massai of East Africa have a coming-to-manhood ritual in which a teenage male must kill a male lion by himself with a spear. I met a Massai tribesman only once, one of the times I was in Tanzania. He as a nice guy–also a born-again Christian–who had no kidding killed a lion with a spear. So, with tools, a human trained in warfare is a much more fearsome creature than you estimate…not that this is a very important point.

My own view of warfare–and I feel confident it’s the correct one–is that God created humans to be cooperative, but because of sin we frequently fail to be, or are cooperative only with our own perceived in-group and are willing to kill everyone in out-groups (though sometimes we kill people in in-groups as well). Sin has been with us from the beginning of the human race, so I would expect war to be very ancient. To say war is a product of sin is of course not saying going to war is always a sin–motives matter and once war exists, at least some warriors will fight to mute the horrifying effects of the way others use warfare. Like how Gordon faced off against quasi-Christian cultists murdering people in the Taiping Rebellion and against the “Mahdi” in Sudan.

As far as the British Empire’s reasons to send Gordon, of course they had reasons that included territorial gain. Though in that period the British public was very much against slavery and the UK military had already shut down the European slave trade. Gordon was fighting the Islamic slave trade, which was centuries older than the European, fighting it with a certain measure of morally-righteous-British-public support, but finding that his superiors in the military and government actually didn’t care about doing the right thing so much. They cared about what was expedient and what built the empire. Their motives though did not change Gordon’s motives. He fought for what he believed in a way that he believed was just. That’s why I see him as a model of a righteous warrior. (Oh and in China the British found it expedient for him to be there to be sure–but the native Chinese loved him more than the British military ever did. A sign Gordon had hit a high level of morality in his actions.)

Ironically, you express doubt about Gordon serving imperial purposes in the Crimean War and that was rather clearly about balance of power between the French, British, and Ottomans on one side and the Russians on the other. Yeah, the Russians were seizing territory the Ottomans once had, but the British and French had no rights to it. They simply didn’t want to have to fight the Russians in the Mediterranean later. Very much a matter of self-interest and protecting their spheres of influence. Gordon’s later battles in China and Africa were in fact much more altruistic and much less along the main lines of what the British government really cared about. So I very much disagree with your historical assessment here.

As for my wars, the Gulf War rather parallels the Crimean War–Iraq was a local power that not only defeated Kuwait in battle, but could have defeated Saudi Arabia and all the oil-producing states in the Gulf. The United States saw this as an economic threat–and a threat to our sphere of influence. So in rather blatant self-interest, we invaded. My personal motives were straightforward–I was a medic in a hospital unit; my job was to save lives, all lives. I did in fact help provide medical treatment for civilians in the United Arab Emirates as well as US military members stationed there…

In Iraq, I advised the Iraqi Military on training. It’s been established historically that the USA did not know Iraq didn’t have WMD (I can explain in detail why) but most of the American public are unaware of the facts. For me personally, I felt the fact Saddam Hussein had used chemical weapons against his own populace justified the war, for the sake of sparing Iraqi civilians. Though in fact the conduct of the war in Iraqi was bungled horribly and put far more Iraqi civilians at risk than Saddam did–however, that was not an inevitable consequence of that war–it was a product of how the war was mismanaged, with many mistakes made. I personally helped the Iraqi military take charge of their training, but we very much knew Iraq needed at least 5 years and more like 20 years before its military would be running well again (in 2008). I felt the Obama Administration was being irresponsible to withdraw from Iraq in 2011–and the subsequent rise of ISIS sadly justified my opinion.

Afghanistan as you mention became a mess with the Soviet invasion and the USA acted in self-interest in getting the Soviets out of there–regional-power play Crimean War type stuff. However, once the weapons we sold Afghans started being used in a civil war in the post-Soviet era, I would have said the USA had some moral responsibility to try to at least broker peace in Afghanistan. But we ignored those foreigners as being beneath us–until people based there attacked us. Then we decided to in effect re-do all of Afghanistan. Again, I think there was a humanitarian reason to do so–the Taliban were horrible in Afghanistan, in particular to women. The USA tried to do good work there. I personally managed funds to build roads, clinics, schools, etc in Western Afghanistan (Farah and Ghor provinces). I had direct control over about 20 million dollars in humanitarian funds at one point. And also I was part of a planning team on how to hand over Region Command West to Afghan control. I in fact by the grace of God enjoy a very clean conscience about what I did in Afghanistan and why I did it. Except for the part where Afghans who worked with us are getting killed because the USA is engaging in a complete and unneeded full withdrawal from Afghanistan right now, de facto handing the country over to the Taliban…yeah that part bothers me…

To change topics a bit, your views on just war strike me as odd. Maybe because you link it too much to self-defense and not enough to humanitarian relief. The Nazis made WWII one of the most clearly justified wars of all time by executing civilians en masse. The only regrets the USA should feel in retrospect about our involvement in WWII was we did not join the fight sooner. Otherwise, our involvement with the effect of stopping the death camps was completely morally justified.

Well, if the Maasai need tools like spears to kill lions and tools are the result of generations of cooperation and innovation: there is not actually much of a disagreement left in there. 🙂

But for all Gordon’s attempts at fairness, it didn’t amount to much in the end. Britain subjugated China, colonized Hong Kong, and funneled the majority of the money and resources back to British hands. Maybe he made it less horrible than it could have been? Yay? And apparently he was an imperialistic cat’s paw in Crimea, too.

I’m much more nihilist about the Gulf War because whatever happy-feely reasons were had about coming to the defense of our ally Kuwait, the reason America is allies with Kuwait is to secure our access to that sweet, sweet dinosaur grease. How many tin-pot authoritarians in Latin America did the US prop up because they were willing to put US interests over everything else, even their own people’s interests? Apparently we’re propping up child-felchers in Afghanistan because the child-felchers are anti-Taliban allies: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/21/world/asia/us-soldiers-told-to-ignore-afghan-allies-abuse-of-boys.html

Yanno, you might be the weird one for associating war (and the war industry) with humanitarian aid.

Side note: I think that I didn’t make the ambiguity of my thoughts on WWII clear. It’s the closest thing the world has had to a just war in recent memory, but on the flip side, what did Germany do that any of the other imperialist country hadn’t done at some point or another? The Germans were just more efficient about it (insert German engineering joke here). Heck, the Nzis admired the Jim Crow laws America had in place. It’s just that the Nzis attacked what was perceived as in-group members like Austria, France, England, et al.

That reminds me, I need to get you to watch The Saga of Tanya the Evil as well as Legend of Galactic heroes. If I ever have the money and a sufficient enough reason to go to that armpit called Texas, I need to track you down so I can make sure a watching party happens. I’ll bring my husband so you can commiserate over the weird crap I shove in front of your faces.

Spear-making requires minimal cooperation among a small group of individuals. It is not an indicator that humans are broadly cooperative by nature–history shows sometimes we are, but warfare has been around since forever. Otzi the Iceman was found with an arrow wound, obviously deliberately given by another human. (Though interestingly bows and arrows require a lot more cooperation than spears–but look how we humans have applied cooperation…)

Of course the Gulf War was about Dino juice–but not about Iraqi petroleum, because we never, ever controlled that. It was about Kuwaiti oil–but as a side effect of self-interest, we did keep a number of Kuwaitis free from Iraqi oppression and prevented the Saudis and others from going down. In other words, ask a Kuwaiti what they think of the Gulf War…yes, this is a case in which I know exactly what I’m talking about, because I have met Kuwaitis.

Also, associating war with humanitarian relief is likewise based on knowledge. The reason to go to war in Rwanda, though we never did, was to prevent Hutus from killing Tsusis. The reason to go to war in Kosovo and Bosnia was to keep Serbs from killing Muslim civilians. We rather slowly went to war there but eventually stopped the ethnic cleansing. There were multiple reasons to go to war in Iraq and Afghanistan–and the good reasons were to help the oppressed minorities in those countries, including women, which we in fact at least halfway did. Girls attended schools built with funds I managed. And I hired local Afghan contractors to build those schools–contractors the Taliban will happily kill while they convert the schools to sheep pens. That’s a fact.

And the reason to oppose Nazi Germany, though of course there were self-interested reasons, was the death camps and slaughter of civilians. AND it is straight BS to imagine every great power essentially does what the Nazis did. Er, no–yeah major powers do bad things, but get a grip on reality, chica. The world was rightly horrified by the Nazis and Jim Crow is not the equivalent to running 11 million people through concentration camps and either working them to death or gassing them. Go ask a Holocaust survivor.

Bruh, I’m not actually denying the violent tendencies of humans. But because it seems to operate mostly on in-group/out-group principle, wouldn’t a solution be to expand the definition of the in-group?

Plus you’d need to add the numbers of Native Americans killed to Jim Crow, but IDK if failure of efficiency actually makes it less morally culpable than the Nazis, yanno?

I’m also questioning the American military as our best use and vehicle of humanitarian aid. And why does it have to be America? Surely you know more people than I do who would screech bloody murder at the idea of the UN coming in force to observe elections in Georgia, where they just passed some BS voter suppression laws? Is it only okay when America does it to “lesser” countries?

We could have just allowed the people in Afghanistan who wanted to immigrate to the US (running into another in-group/out-group problem with our homegrown racists) — not a perfect solution, but arguably a better one that doesn’t involve nearly so many civilian casualties. Heck, it’s why the Twin Cities has a large Hmong population.

I think that’s why I like the Japanese take on war (albeit through the medium of cartoons). They’ve been on both sides of the coin for warfare and occupation.

Bonus reading: https://noahpinion.substack.com/p/fourth-of-july-thoughts?r=elvx&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=email&utm_source=copy

Good post, and I have a lot of thoughts on the different aspects presented, but for now I’m going to hone in on a particular part. You said the idea of certain acts meriting punishment is falling out of favor in our modern society, and to a great extent I disagree. Maybe in some instances it’s falling out of favor, but most people definitely still think certain acts deserve punishment. They’re just shifting their view of what to punish and to what extent. Many people(or at least the loud ones) pushing for social change do see themselves as fighting for others or the greater good.

A lot of loud modern activists partially fit your description of a Self Styled Righteous Warrior. Many of those people do feel like they’re in the right, fighting a just war and all that. But since they’re human, they either misinterpret what’s actually right or wrong, or else have a skewed idea of how to react to wrongdoing when it occurs. And in many cases, there seems to be a trend toward demanding HARSHER reactions to those they disagree with, rather than the opposite.

You make a very good point here. What I was referring to though was punishment by law–that is, sending someone to jail, fines, capital punishment. More and more people are against formal punishment by law.

But at the same time, you are quite right, there are many people who believe in punishing people by public humiliation, shaming, and cutting off social contact. Though actually there are some people who also believe it is legit to physically attack someone under certain circumstances or destroy physical property.

So I suppose I have judged wrongly in saying people are against punishment–they are not. They are simply against punishment via the legal system and instead favor what we could consider private justice. I suppose THAT is a product of people believing their own sense of right and wrong is more just than “the system,” which can be a very dangerous way for people to think.

Your criticism about what I had to say was completely valid. Good point.

But you also have a point that there are people who do things like advocate for prison abolition. (And YOU have a point, and YOU have a point)

It’s not that they want to do nothing, it’s just that they think that overt punishment like prison does nothing to actually solve any underlying problems. (A lot of this depends on our definition of “punishment,” but prison is a convenient point of contention.) And even some people in favor of most forms of prison abolition still think it’s necessary to sequester dangerous people who would harm others. But they don’t advocate for prison for things like property crimes. (Spoilers, I think they also have a point.)

Obligatory ootube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDcwIZzaf-k&ab_channel=PhilosophyTube

I could agree with a sensible program to get rid of a lot of prison sentences. However, certain acts merit the death penalty (intentional murder, sex slavery, and a few other crimes) and if we choose not to execute people who commit these particular acts for humanitarian reasons, we should be willing to lock up these people for life. Because there are some things people do that threaten society so much a person who does them in essence forfeits his life.

That’s something worth debating, I think, whether forfeiting your freedom is equivalent to forfeiting your life. More to follow after I hash it over

Okay, if we’re gonna do something as gauche as comparing suffering, we should at least be scientific enough about it to ask some good questions.

Is a “clean” death better than suffering? Is suffering better than death if there is a possibility of change? What if there was no improvement?

To loop back to previous comments, do you consider the Holocaust worse than any other genocidal crap people and countries have pulled? Why is that?

As long as we’re being gauche, I think the Holocaust absolutely can be compared to Jim Crow/slavery or the treatment of Native Americans. The Holocaust was what, ~ten years of concentrated torture, cruelty, and terrorism? If we only count American responsibility for enslavement/Jim Crow or the American Indians as being since 1776, that’s still at least 200 years of torture, cruelty, and terrorism spread over more people and more generations.

Is it better to die cleanly/honorably (whatever “honorably” means) or to live to possibly see an improvement in future times?

There’s an evergreen topic for ya, because it can be applied to quite a range of things, from legal reform to voluntary euthanasia to veganism to infant abandonment.

Why is the Holocaust worse? The truth here is in modern times the word “genocide” gets overused. African slavery in the Americas was a horrible thing–but it was not a genocide. It was never anyone’s policy to kill all African slaves. Obviously, right? Because how are people going to work for you if you kill them all? Yeah, lots of people died, lots of abuse, yes, true, but it was not any kind of deliberate genocide.

Likewise with American Indians. While there were incidences in which white people killed defenseless people (women and children) and where individual attempts were made to wipe out a particular tribe, it was never English colonial policy nor United States policy to kill all the Native Americans. Instead, English and American law saw tribes as sovereign nations with a legal right to exist and yes sought to limit the land the tribes occupied but never denied the tribes have a right to have land and never tried to kill them all as official US policy. Even the efforts to separate Indians from their culture were not entirely systematic. So, “genocide” is an exaggeration when applied to Indians. “Partial attempted genocide” is more true–though in fact diseases that no human being could control killed more Indians than any white person ever did. Even with a handful of cases in which white people deliberately exposed Indians to smallpox were not in the same category as genocide–because smallpox was already there. The disease had already spread, in advance of direct white settlement.

This is in contrast to the Germans deciding to kill every Gypsy in Europe and every Jewish person. And then build gas chambers and set off to killing them, all of them they could find. Then putting Eastern Europeans to work in munitions plants but neglecting to feed them and crowding them into unsanitary conditions, so like 2 million ordinary Poles died–not in death camps, in labor camps.

The worst bloodbath in US history was the Civil War and the worst camps in USA history held POWs from the North and South, especially Andersonville in the South. However, we would not call the bloodbath of the Civil War “genocide,” would we? Why not? Because it was never Union policy to kill all Southerners and it was never Southern policy to kill all “Yankees.”

This like the difference between first degree murder and manslaughter. Intent matters–as does killing millions of people verses setting up a legal situation in which eventually led to Indian casinos dotting the land.

Progressives often see history through the light of “I hate USA!” goggles but what I just said is clearly true and not hard at all to substantiate.

Okay, sure, but I still disagree on some points.

For example: “It was never anyone’s policy to kill all African slaves. Obviously, right? Because how are people going to work for you if you kill them all? Yeah, lots of people died, lots of abuse, yes, true, but it was not any kind of deliberate genocide.”

Then vis-a-vis with this: “Then putting Eastern Europeans to work in munitions plants but neglecting to feed them and crowding them into unsanitary conditions, so like 2 million ordinary Poles died–not in death camps, in labor camps.”

The second pretty much what happened with a lot of plantations, yanno, but you’re using it as if it’s worse than plantations. But I will give you props for showing an understanding of systemic vs individual discrimination.

And I guess we disagree about the concept of cultural genocide. It seems like feeding into racist rhetoric to keep putting so much emphasis on genes, even if in the opposite direction. Because you absolutely can make culture with other people’s kids.

Also I think we need to recognize that capitalism absolutely is short-sighted enough to destroy the source of its own wealth if not kept in check.

@Travis:

Yeah, you’re right, a lot of people primarily focus on punishments based in various forms of social pressure. One caveat, though, is that the legal system tends to follow social attitudes in a lot of cases. If people feel that something is so desperately wrong that they’re willing to do nearly anything to enforce that moral standard, (even justifying/brushing off heavy attacks that damage the career, mental health, and sometimes physical safety of whoever disagrees with them), it doesn’t take much more for people to consider enforcing their moral standards through the legal system. At that point, those people are more likely to just see it as common sense — if something is extremely horrible, why WOULDN’T the law be expected to intervene?

Some places are more apt to use legal enforcement than others, though. I’ve heard that the UK has less free speech protections in some cases. I Still Find That Offensive by Claire Fox talks about that a little bit, and even cites a few cases where people faced legal punishment for speech. I haven’t read past the preview on Amazon or looked into the particular cases she’s talking about, so I can’t vouch for them. But the types of situations are at least worth thinking about. Especially as we consider that this next generation of people (in many cases raised with little capacity to cope with those that disagree with them) are eventually going to be the ones making/enforcing laws:

https://www.amazon.com/Still-Find-That-Offensive-Provocations/dp/1785904167/ref=sr_1_2?dchild=1&keywords=claire+fox&qid=1625681953&sr=8-2

That is an inspiring post, Travis.

We need to be able to see true heroes, to realize there have been some, despite their flaws, despite accusations against their persons and deconstruction of the very idea of a hero that, it seems to me, is weirdly common today, outside of fiction at least.

Why do we love to destroy “good” people, heroes and heroines alike? (I see feminist attacks against masculinity, and it bothers me. I especially dislike the treatment of Fathers, which I see a lot in movies where they are represented as either tyrants or spineless hen-pecked puppies. Not the pillars of strength they can be, though flawed. In my opinion, men and fathers are indispensable to the stability of the home, and there is a reason they are under attack. I have been blessed with a father who taught me so much about goodness and kindness and right even though at times he was tyrannical.) And flaws do not always destroy the good someone does in their life, by God’s grace.

It is interesting to me that often what feminists attack in the real world is essential to good fiction (who could be honestly romanced by a spineless man? Or a tyrant? It is usually the strong, kind, gentle man with a spine who is willing to give it all for right who is attractive to most people. The same for men (I think) they admire women who express these characteristics in their own way), and it also seems to be that kind of masculinity that draws a woman to a man in romantic relationships – which is not only his physical strength, but is a part of it.

People who try to do right, who pursue it in themselves and others, who seek goodness and believe it is found in God’s laws (not our private interpretation of them, as you clarified), who believe goodness is possible, even expected – we need people like this more than ever. To inspire us to love others with that self-sacrificial love you mentioned.

What you talk about shows us we are not simply brutes, driven by our desires to destroy, nor angelic beings walking without wrong – we are in the middle, and as a human, may choose the road to one or the other. And only by God’s grace can we escape becoming a brute, or rather a worm, as the Bible puts it.

And the warfare you speak of extends beyond just the physical aspects of warfare into the warfare of the heart. I think you could say physical warfare is usually an extension of spiritual warfare, since that is where our motives come in.

I appreciated your post on your own war experiences also. It gave me a much bigger view of some of the things that went on between countries, and how the involvement of any single one of us, if we are in the fight, is not necessarily dictated right or wrong by the beliefs, reasons, and motives of those running the war, or our superiors.

Thank God we are responsible for our actions and not those of others, beyond what we should try to change, that is.

And your comment about people seeking to be a law unto themselves is correct and frightening for the future of our land. But then I remember God is here. He is using what satan means for evil for good. And that is a truth to put heart in us for the fight, whatever may come.

Thank you for the encouraging topic, keep the good stuff coming!

Thanks so much for your comment. I’m glad you found this article inspirational.

I find Gordon inspirational. No, he wasn’t a perfect human being (not that there is any such thing short of Jesus Christ), but he believed in fighting for people in distress and did so with no sense of personal gain. He willingly sacrificed self.

Of course you are quite right that the key battle every human faces runs right down the middle of our hearts. We can surrender to our own wickednesses or fight them–and if we fight we can fight for the sake of our pride–or through the power of God and the Holy Spirit. I think the evidence is clear where Gordon drew his strength (though again, he was not a perfect person).

Yes, some people do attack all forms of genuine heroism and I’m not entirely sure why, though I have my suspicions. In this article I reacted to a counter-reaction that embraces hero-worship of all things perceived to be masculine, which would make a hero out of George Armstrong Custer, who was not devoid of courage and other admirable traits but fell far short of what I would consider a hero. So I do favor recognizing heroes–but not every warrior has been a hero, even if he’s been good at combat.

God bless you!

Thanks for your reply, Travis.

Gordon is inspiring, I agree. Partially because of where he drew his strength from, and also because of the fact that he is imperfect and yet heroic, giving us another marker of what is possible, and what God can accomplish through us. It’s wonderful!

And I do see your point that not every good warrior is a hero – a fair number of them have been despicable killers. As you say, a lot of the difference between a hero and a warrior who is not is in the motives.

Thanks for the great conversation!

And have a blessed day.

If you want to read about example of a warrior, read about Witold Pilecki. He wasn’t a Christian but one can learn a lot from him.