Our second stop in our solar system tour lands on Venus, a planet long considered to be much like Earth (though wetter and warmer), then recognized as nightmarish hellhole (with every single day hotter than Mercury at its worst), but after that seen as having some prospects for colonies anyway. Venus was never as popular in old science fiction as Mars, but nonetheless many kinds of speculative tales set themselves on Venus, probably second in fictional prospects for settlement in our Solar System only to Mars. Far more popular than Mercury.

What’s Venus Got For Survival?

For an overview of human survival needs that applies to any planet, please reference last week’s post on Mercury, which covered that.

What Venus Is Like (Hellhole, Anyone?)

Venus is nearly the same size as Planet Earth, meaning the gravity humans need to avoid atrophy and to allow for embryo development is likely to be enough on Venus, which has 90 percent of Earth’s surface gravity. Venus’s gravity is enough to contain a substantial atmosphere–in fact, its atmosphere is 92 times denser than Earth’s.

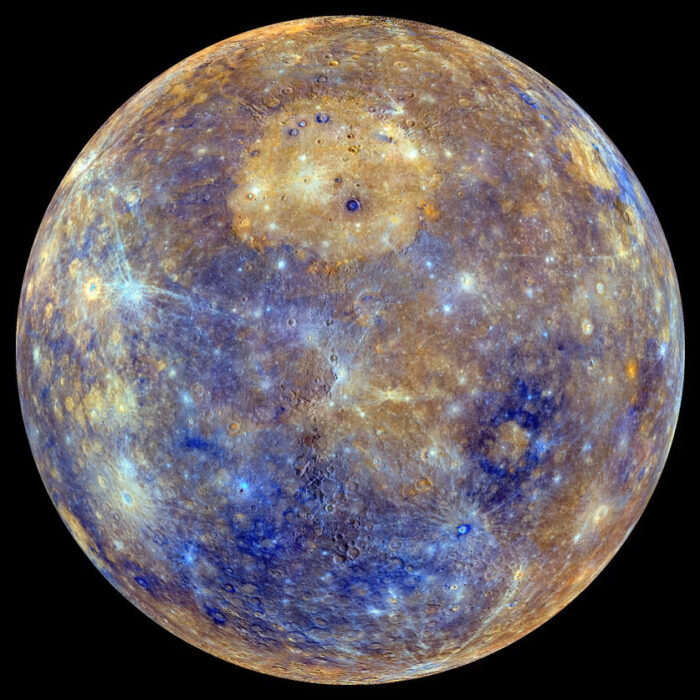

Venus, with color enhanced. Credit: NASA.

Which is the cause of Venus-is-a-hellhole thing. The atmospheric pressure on the surface is equivalent to about 900 meters (3,000 feet) under the ocean on Earth–a pressure humans can actually survive given time to build up to it (breathing a mixture of helium and oxygen), but which is dangerous and would instantly crush an unprepared person. The atmosphere of Venus is also devoid of oxygen, consisting mostly of carbon dioxide with traces of nitrogen, argon, and other gasses.

Venus is entirely cloud-covered, but those clouds aren’t made of water vapor like clouds on Earth. They’re made of sulfuric acid, which can dissolve a human being and most things we build in short order.

Oh, and did I forget to mention the temperature? The average surface temperature is 737 K (464 °C; 867 °F) on the surface, heat driven by a greenhouse effect gone wild. By the way, that’s hotter that the hottest spot on Mercury when Mercury is directly facing the sun over its long, slow day. And the peachy thing is the thick atmosphere of Venus makes it so that the incredible heat of the planet is pretty much spread around everywhere, both night and day, poles and equator.

For what it’s worth, Venus also has a strange rotation, the opposite direction of every other planet in the Solar System, so that the sun would rise in the west and set in the east. It also has the slowest rotation at 243 Earth days–which is longer than the 224 Earth days of its year. (Venus is the only planet in the Solar System with a day longer than its year.) However, because of the retrograde rotation, the length of a solar day on Venus (the time it would take an observer on Venus to see the sun cross the sky) is significantly shorter than the sidereal (actual) day, at 116.75 Earth days. Not that you would be able to see the sun through the thick clouds and dense atmosphere, not from the surface anyway.

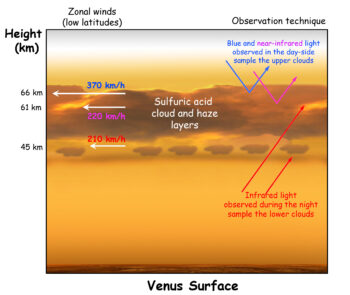

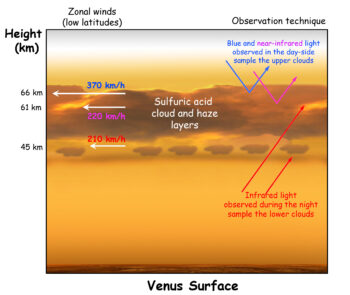

Winds on Venus, image copyright Universe Today. Note 370 kph is 222 mph and 220 kph is 132 mph.

What would be a tremendous heat differential between the day and night side has spawned massive winds to even out temperatures at the level of the clouds that circle Venus approximately every six Earth days, blowing hundreds of miles per hour. It seems the atmospheric motion causes lightning strikes on the surface, though instruments on space probes to Venus have given contradictory data on whether the surface gets hit by lightning or not.

Oh and the surface also seems to have some active volcanoes, with plenty of evidence of lots of past volcanic activity. So if the crushing pressure, furnace-level heat, darkness, and lightning strikes were not enough, there’s also volcanoes! (Hence my use of the word “hellhole.”)

What Could Possibly Be Good About Venus?

Well, as already mentioned, Venus has enough gravity to make worries about bone loss over time unlikely. Venus’s thick atmosphere would also provide radiation shielding. Copious carbon dioxide can be processed to separate out carbon, which is a pretty good building material, and oxygen, a human basic (or “nutritional”) survival need. Sulfuric acid contains hydrogen, which can be separated out and added to oxygen, meaning it’s possible to generate water on Venus. (In fact, all the chemical elements life needs to survive are available in Venus’s atmosphere.)

Wind motion, probable lightning, and solar energy (if high enough in the atmosphere), provide plenty of power for cooling and for growing plants. Which of course doesn’t matter at all if you are going to be burned/crushed and struck by lightning/covered in lava. However, the surface of Venus isn’t the only option available.

A concept of high-atmosphere living on Venus. Image by NASA.

What if human beings were to build a cloud city on Venus, parallel to what was imagined to exist on Bespin in Star Wars? What if we were to fill airships with lifting gasses and create habitats in the clouds?

The fact is that carbon dioxide is denser than the mixture of oxygen and nitrogen that human beings normally breathe. That means you wouldn’t have to do anything special to get breathable air to float in Venus’s atmosphere. Just fill a balloon at a pressure comfortable to humans and it will naturally rise to about 50 kilometers above the surface of Venus.

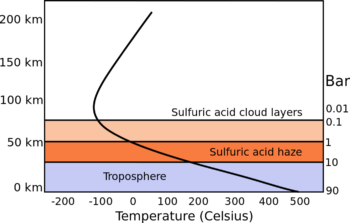

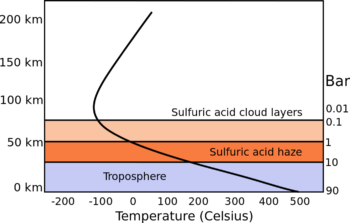

Since the atmosphere of Venus gets both colder and thinner at higher elevations (just like the atmosphere on Earth), the level at which a balloon full of regular air would naturally stop rising would be a place where temperatures and pressures would be much more survivable than the surface. In fact, the level of 1 atmosphere on Venus (at 50 km) is bit on the cold side for humans, close to freezing, but just a bit lower gets into atmospheric pressures humans can adapt to at comfortable temperatures.

A chart of temps and pressure on Venus. Credit: spacestack.

Note that a city in the clouds would never have to touch down on the surface of Venus. It could generate new building materials from atmospheric carbon and other elements floating around and also generate the oxygen and water and minerals for plants, all from high in the sky, without ever touching down on the surface of Venus.

However, I should mention that the artistic image by NASA of living above the clouds isn’t how things would actually be. Well, not if living in the best place for survival. First, the clouds provide important protection against solar radiation. Second, the optimum pressures and temperatures are within the cloud layer, not above it or below it…yeah, that’s right, within clouds of sulfuric acid…ahem…(though of course it’s possible to make materials that will shrug off sulfuric acid).

How Has Science Fiction Seen Venus?

Now that we’ve looked at what Venus is actually like, what did science fiction speculate about Venus? Was anyone in the past thinking of cloud cities? (On Venus, mostly no.)

Cloud-Covered Venus: Ocean or Swamp?

But early astronomers couldn’t help but notice that Venus is always covered in clouds. They wondered why that would be. Having limited knowledge of Earth–that is, they had no way of knowing that no part of Earth is always covered in clouds–they imagined Venus might be covered in oceans, where the clouds on Earth originate–and that would be sufficient to explain the continuous clouds. Or maybe swamps would do, which are often foggy. (In fact, the Star Wars concept of Dagobah, Yoda’s home planet, is probably influenced by earlier science fiction stories of Venus-as-a-swamp.)

Another feature of early Venus stories, especially the campy ones, was to borrow from mythology and imagine Venus somehow connected to women. Since, you know, Venus was a female goddess. So the oceans and swamps of Venus tended to be filled with scantily-clad Amazon women.

The Venus in Fiction Wikipedia article details the stories which imagined Venus as an ocean world or a world of swamps, but I will take note of two particular stories. The first because it be of interest to Christian fans of speculative fiction. That is, C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra, book two of his space trilogy.

By imagining Venus as a younger world than Earth, Lewis set up the drama of the Garden of Eden happening over again, with the human characters from Planet Earth serving as the tempter and almost as an angel of light, to the equivalent of Eve…which kinda repeated the stereotype of Venus and women, but in Lewis’s case, he did so tastefully. While Lewis’s choices and his story are interesting, what he did with his space stories was imagine that Planet Earth alone was an abode of sin and it as a result was effectively quarantined from the rest of the stars and planets.

What if he had done the same thing with his fantasy? What if Lewis had imagined that Narnia was a world where people crossed over from Earth to tempt the equivalent of Eve (in an alternate time due to an alternate “dimension”), but then when the temptation was over, they would never be allowed to come back? Such a story would be an interesting one-off tale, but would discourage anyone else thinking about similar stories and close the door to any sequels…which is exactly what Lewis did in his fantasy versus his science fiction. In fantasy he left the door open, but in science fiction, he closed it. Which is why I think Perelandra versus Narnia partially explains why Christians are more interested in fantasy than science fiction. But anyway…

The second story world featuring Venus I want to mention came from the short stories science fiction pioneer Stanley G. Weinbaum set on Venus. He imagined Venus as tidally locked to the sun, so that the very center of the sun side would be a blazing desert, but the desert would be surrounded by a jungle, surrounded in turn by a ring of temperate lands, surrounded in turn by icy terrain near the dark side, melting and providing water for the light side (with no cheesy Amazon women, by the way). My reasons for mentioning this story is not only do I think it was awesome, I re-packaged Weinbaum’s planetary adventures, which made no sense around Planet Earth, and imagined them taking place around another star (with the help of Heather Elliot and Cindy Koepp). Available on my website under: Worlds of Weinbaum.

A Third Vision of Cloud-Covered Venus

In 1922 scientists tried to read the composition of the atmosphere of Venus–and found no evidence of oxygen. So, some old science fiction imagined Venus to be a windswept desert, covered in toxic dust clouds, which maybe a human might be able to live on, but barely. This was by far the least popular version of Venus in fiction, but the one closest to being true. Which goes to show that humans are not necessarily drawn to realism in fiction. (Yes, scantily-clad Amazons by a world ocean really do appeal to male readers of science fiction more than explorers barely surviving on a desert Venus. Go figure. đ )

Terraformed Venus

It wasn’t until the Soviets sent landers to Venus in the 1960s was it evident what kind of planet Venus really is. The realities of furnace-level heat, crushing pressures, acid clouds, and all the other “fun” features of Venus caused the popularity of Venus in science fiction to plummet considerably.

However, some science fiction authors switched to imagining Venus as a terraformed world, thinking that at some point in the future the terrible conditions of Venus would be made better. Kim Stanley Robinson, better known for his series about the terraforming of Mars, imagined Venus made suitable for human habitation by putting up a giant sunscreen and collecting the carbon dioxide atmosphere as it would freeze out, then seeding life and water (via comets) in the atmosphere.

The Victorian Venus anthology I supervised imagined much the same thing and included orbital shades to keep the temperatures moderate, though I never detailed the terraforming process–and I imagined much of the extra CO2 would be sent to Mars, rather than buried on Venus, as Robinson imagined (and of course I imagined Victorian culture being largely reproduced as well). But still, most of the modern stories featuring Venus imagine transforming it into a place where people can walk on its surface.

Cloud City Venus

The most realistic vision of how to live on Venus isn’t particularly popular in fiction. Geoffrey A. Landis‘s “The Sultan of the Clouds” (2010) features habitations in the clouds of the second planet of the Solar System, but my research for this article didn’t reveal any other stories set in Venus’s clouds.

Bespin. Copyright: Disney.

However, Star Wars, with its interest in unique planets dominated by one aspect such as a desert world, ice world, swamp world, urban world, naturally produced a vision of a city in the clouds featured in Empire Strikes Back. However, this Star Wars version imagines the city floating over the clouds, not buried inside them, where people would not be able to see even a hundred meters through dense obscurity. And in fact, the best place for a Venus colony would be in the clouds, not over them.

A Psychological Need to See Skies?

I admit my thoughts of living buried in a cloud that you could not face for one moment without protection from acid, not being able to see more than a hazy glow of light around you, living every moment in a carbon-fiber inflated dwelling, from which you never dare fall off, lest you plummet into crushing pressure and lead-melting heat, does not appeal to me very much.

I find the idea of living on Mercury much more appealing–at least on Mercury you could walk on the surface at night, though you’d have to be in a spacesuit. And maybe vast underground chambers are available for use on Mercury, on which images of the stars could be projected, like a planetarium, and where trees and other plants could be put into the ground–yes, using artificial soil, but still, on the ground somewhere.

But the idea of living on Venus appeals to me a lot more if the cloud city were above the clouds, even though that isn’t the optimal place on Venus for survival. (In fact, even the artist working for NASA portrayed their futuristic dwellings on Venus as above the clouds, not within them).

I’m not claiming to say anything profound here–who wouldn’t rather live in a beautiful city above the clouds than within an acid cloud? Maybe a colony on Venus could in fact fly above the clouds, using shielding to deal with excess radiation and otherwise compensating for less than ideal pressure and temperature. Or perhaps the airships of Venus could rise about the clouds on a regular basis, say on holidays or vacations, but return to the practical levels of being within the clouds afterwards.

But perhaps it’s worth noting that having a view of skies, at least at times, may count as a human need as much as gravity and oxygen and warmth…

What’s Unique About Venus

Closest Neighbor

So what makes the second planet in the Solar System better for a colony than anyplace else? Well, overall, it probably isn’t the best, but it does have some strong points.

For the record, at its closest approach, Venus comes closer to Earth than any other planet. Also, the window for closest approach to Venus comes more often than the window to Mars (584 days versus 780 days, as mentioned in this Wikipedia article on the colonization of Venus). So Venus is literally the easiest planet to get a spacecraft to from Earth.

Gravity

What may be the strongest point has already beeen mentioned, that is, Venus has nearly has the same mass and density as Earth, so the pull of gravity is 90% of Earth’s. The fact is nobody knows what the minimum gravity requirement is for human beings. Over the long-term we’ve done zero gravity in the ISS and other space stations and established conclusively that microgravity isn’t enough for human long-term survival. But no long-term experiments have been done in low gravity. If 38 percent gravity is enough to allow for human embryos to develop normally, Mars and Mercury are viable. If even less gravity is enough, say 16 percent, a lot of bodies in outer space have enough gravity, such as Earth’s moon.

But if the minimum requirement for gravity for humans to develop normally proves to be say, 70% of what we find on Earth, then Mars and Mercury might possibly work if pregnant women spend nine months in a centrifuge to stimulate normal bone growth–but that’s not very realistic. In case the actual requirement for human life for gravity is high, then Venus is pretty much all there is, other than Earth. (Unless we want to discuss living in the atmosphere of a gas giant…which I in fact plan to bring up…)

Downsides

Other than the downsides already mentioned (acid clouds, crushing pressure and searing temps on the surface, lightning, volcanoes), Venus has the issue of its clouds moving around the planet as quickly as they do. The issue isn’t speed here so much as turbulence. In fact, the wind patterns seem pretty predictable, so once in the atmosphere, a settlement would move around in the wind without much getting shaken up…maybe. I don’t think the data is conclusive on this. Living in the clouds over Venus might be too dangerous, because of changing wind speeds. It could be from time to time, shifts in winds could be dangerous to human life.

The other big problem is getting away from Venus–without any ability to land on the surface, the means to leave Venus’s gravity (higher than Mercury or Mars) would have to use self-contained spacecraft which would have to be suspended on airships before takeoff. A technological hurdle–not insurmountable, but I can’t imagine leaving Venus would be easy. (“Landing” on Venus though could use plenty of air braking.)

And, if we are going to talk about physical security from attack, living in an airship that only has to be riddled with holes in order to sink to unbearable depths below may be rather less than optimal…

Conclusion

What are your thoughts, if any, about fiction set on the second planet in our Solar System? Lewis’s Perelandra, or anything else? Thoughs on Bespin? Dagobah?

Could you ever imagine yourself living on Venus? Would you be able to live in a cloud city?

Would you rather be above the clouds rather than in them, even if living in them is safer? Do you think humans would be able to adapt to living in a place where they never saw the skies?

What other thoughts do you have?

them. This may be true, and most often is.

them. This may be true, and most often is.

horror element, Alzheimerâs and its effects doesnât become the focus of the film but the plot device that brings about something more sinister to the forefront.

horror element, Alzheimerâs and its effects doesnât become the focus of the film but the plot device that brings about something more sinister to the forefront.