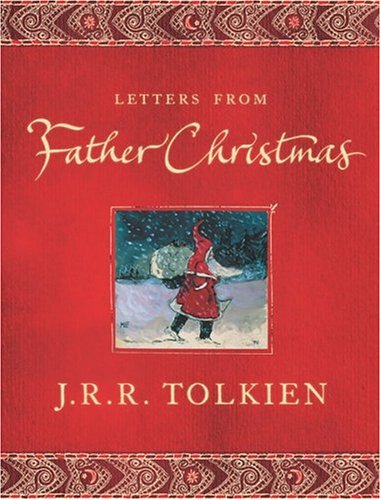

On Tolkien’s ‘Letters From Father Christmas’

Even those naughty families who’ve been very, very bad this year — by implying or telling their children Santa Claus truly exists — have surprising company in the form of a Christian classic author.

Yes, I speak of very myth-maker behind the Biblically derived concepts of myth-become-fact and “eucatastrophe,” and the classic fantasies The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. J.R.R. Tolkien didn’t shy from Santa, or make historical appeals to St. Nicholas, or vaguely reference the fantasy icon of Santa, or “allow” Santa with default suspicion because Christmas is truly Jesus’s birthday.

Tolkien instead pulled off an elaborate deception. Year after year, Christmas after Christmas, he went beyond the cliched — but I recall highly effective — partly eaten cookies and milk and carrots for the reindeer.

Instead, Tolkien being Tolkien, he wrote letters “from” Santa. In his own hand. With drawings. Color drawings. And custom “Arktik” runes. Along with a mini-mythology of Santa, the North Pole, and at least one comically clumsy polar bear who should not attempt DIY projects. Then Tolkien sent these letters to little John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla Tolkien. Yes, I am afraid this patron saint of myth-in-perspective outright lied to his own children.

Cliff House

Top of the World

Near the North PoleXmas 1925

My dear boys,

I am dreadfully busy this year — it makes my hand more shaky than ever when I think of it — and not very rich. In fact, awful things have been happening, and some of the presents have got spoilt and I haven’t got the North Polar Bear to help me and I have had to move house just before Christmas, so you can imagine what a state everything is in, and you will see why I have a new address, and why I can only write one letter between you both. It all happened like this: one very windy day last November my hood blew off and went and stuck on the top of the North Pole. I told him not to, but the N.P.Bear climbed up to the thin top to get it down — and he did. The pole broke in the middle and fell on the roof of my house, and the N.P.Bear fell through the hole it made into the dining room with my hood over his nose, and all the snow fell off the roof into the house and melted and put out all the fires and ran down into the cellars where I was collecting this year’s presents, and the N.P.Bear’s leg got broken. He is well again now, but I was so cross with him that he says he won’t try to help me again. I expect his temper is hurt, and will be mended by next Christmas. I send you a picture of the accident, and of my new house on the cliffs above the N.P. (with beautiful cellars in the cliffs). If John can’t read my old shaky writing (1925 years old) he must get his father to. When is Michael going to learn to read, and write his own letters to me? Lots of love to you both and Christopher, whose name is rather like mine.

That’s all. Goodbye.

Father Christmas

Was Tolkien sinning?

Did his children as a result of his “lies” inevitably fall into wickedness and atheistic hatred of Christians?

Even if they did, why exactly would Christians care about listening to atheists reasons/excuses for rejecting Christ? Won’t such skeptics also tell you that they never ever met a Christian who wasn’t a hypocrite or that the Church only leads to worldwide evil?

How did you grow up thinking about Santa? How does this — for it inevitably will — color your view of the Santa fantasy now?

We have plenty more to help you explore the Santa subject, in previous years and in this year’s Don’t Ditch Santa series.

My family never did Santa. I suspect Dad had some reason about the secularization or the distraction from Jesus, but Dad is one of those types who doesn’t see the point of fiction in the first place. I’m sure Mom didn’t care one way or another, and not doing Santa is easier than the cookies and milk and letters and whatever other rituals parents do.

Though they did take me down the Lions Club to see Santa when I was three or four, and of course I cried. Why do parents insist on doing that to their children? For the lulz?

Fascinating, thanks!

Tolkien personalized the myth specifically for his own children, and I think that is awesome. Tolkien’s method seems better than the parents’ half-hearted attempts to create an illusion with milk and cookies and different wrapping paper. It has less potential to cross into uncomfortable territory, because even though Father Christmas might not have literally written those letters to the children, their own father did. In essence, Tolkien became Father Christmas for his children.

This also makes me wish that I still knew how to have fun. This year, I didn’t get “into” the “spirit” of the holiday, and I decided that it’s okay not to get excited about Christmas. All days are alike to God, and we can honor Him whether or not we choose to celebrate or to make merry on any particular day. For the same reason, I don’t think Christian parents who choose not to create a Santa fantasy for their children are sinning. They wouldn’t necessarily be sinning even if they didn’t celebrate at all, although their reasons for not celebrating would likely be very warped.

But when you can experience that kind of pure wonder without bothering to ask whether or not the source of the wonder is “true,” then that is something truly special that should be cherished.

(Edited to add)

I did grow up with Santa, and for the earliest years that I can remember my parents did put a fair amount of effort into the illusion. I think I caught on that it wasn’t real fairly quickly.

The way fiction haters’ “minds” work both fascinates and astonishes me. So much of this is based on personality, after all. Some people — including Christians — just simply do not possess a creative temperament, do not understand the need for creative people just to create, and furthermore, see no meaningful purpose in it. Fiction haters — and Santa haters, I must say — fall into this category, and Christians who do this forget, as always, God’s wisdom expressed in Romans 14, the Forbidden Chapter, since evangelical Christianity in this country craves conformity in Christian practice and condemns those Christians who fail to comply. Whether “to Santa” or “not to Santa” is not the question to ask. It is like eating or not eating meat offered to idols. God has room for both practices, as long as the HEART (caps for emphasis and perhaps a bit of yelling) is right, i.e., we do what we do or refrain from what we refrain to His honor and glory. My family when I was a kid growing up “did Santa,” but when our own children were small we did not. I instead told them the stories of the real St. Nicholas and how the Santa Claus mythology came into being. That was our choice, “not eating meat.” For those who do indeed “eat meat,” i.e., “do Santa,” it’s not my place to judge. Who am I to judge another? By his or her own master he or she stands or falls. Whatever we do, or do not do, let us always ensure we glorify God and serve Him with an honest, open and loving heart. Romans 14.

Did Tolkien deliberately lie to his children? Yes. Is it a sin to deliberately lie when there are other feasible options available? Yes. Does A=C if A=B and B=C? Yes.

I honestly don’t see what’s so complicated and nuanced about this. So what if Tolkien lied in order to inflame his children’s anticipatory imaginations? Aren’t there other means by which he could have done so? Of course there are! That’s what the entire Season of Advent was invented to do!

Is it possible for me, a relatively enlightened, mature reader, to appreciate Tolkien’s Father Christmas letters for the fiction that they are, and to perhaps glean truthful themes therefrom? Surely. But I have the advantage of having peeked behind the curtain. I can afford to stand firmly atop my adult understanding and wax eloquent about what the letters represent, what they allude to, and what they’re intended to accomplish. And perhaps, were I to do so, I’d even be correct. Perhaps the letters achieved their aim in their target audience. Perhaps they inflamed little imaginations without simultaneously setting those imaginations up to crash and burn when the cold hard truth was at last unveiled.

If so, does that signify that the end justifies the means? Does A not equal C when A=B and B=C?

In a universe where mathematical logic governed all truth, that would be a valid criticism. But I think we should leave that kind of overly objective rationalism to the atheists.

Tolkien’s children really did receive letters from Father Christmas, only “Father Christmas” to those children was Tolkien himself. When the children got older, they would have realized that the story of the mythical Father Christmas merely told the truth of their earthly father’s love for them. Perhaps they might have also made the connection to the love of their heavenly Father.

Not that I don’t feel conflicted about the notion of telling children that the tangible presents that they actually touch and open on Christmas morning were literally brought to them by Santa. I do. But Tolkien’s letter writing seems different to me. It seems like a form of imaginative roleplaying.

I understand what you’re trying to say, but Tolkien’s well-intentioned deception would’ve only counted as ‘imaginative roleplaying’ if both parties had known his letters were fictional. As it was, however, one party (Tolkien) was in the know while the other party (his children) were in the dark and at the mercy of his definition of reality. Yes, the children turned out fine, at least as far as we know. But ends by themselves never justify means. And I have yet to see a justification for the Santa Deception Tradition which can overcome the fact that it’s simply not true.

And yes, truth is ‘mathematical,’ if that’s the word you want to use. A thing is either true, or false. And if it’s partially true, then it can be further reduced to elements which fall into those binary categorizations. I realize that it may have become unpopular to speak in absolute terms on a site dedicated to God-glorifying speculative fiction — i.e. “lies which reflect truth” — but that doesn’t change the fact that if any given truth is relative, then it’s no truth at all. We Christians believe in consistent morality because we believe that God is unchanging, and that all true morality is but a reflection of His innate nature. And it’s not in God’s nature to lie (Tit. 1:2; Heb. 6:18; etc.). Yes, visions sent via the Holy Spirit typically read as fantasy. Yes, Jesus taught in parables. But those means of communication were and are obviously unintended for literal interpretation, for the same reason that no modern fantasy author intends his readers to walk away from a book believing that literal dragons exist in the real world. Tolkien’s Father Christmas letters never made such a distinction. They appropriated the guise of fact in order to deceive those unable to tell the difference.

God is a real God. We don’t need to wonder whether what He’s revealed is true. When we die, we won’t suddenly find out that the story of Jesus was all just a big hoax, but that it was all okay because the idea of Jesus sparked our imaginations, comforted us in our loneliness, and inspired us to shake off sin and strive toward perfection. Heck no! As Christians, we don’t need to lie to our children about some fat, bearded, magical toymaker (or even about a loving, powerful, fatherly saint) in order to sweep them off their feet with tales of comfort and joy. Our tales of Christ are true! Why on earth would we want to undercut our witness to the eternal truth of the Incarnation of God by perpetuating the falsity that an ermine-clad philanthropist squeezes a bulging sack down the chimney at midnight? The former truth is vastly more wondrous, more magical, more starkly awesome than the latter falsehood, and, if it doesn’t seem so, then I say one needs to refresh one’s view of reality.

*clambers off soapbox, deliberately decelerates breathing*

But I doubt that Tolkien intended to deceive his children. Tolkien was obviously a learned man who knew how to face the real world, and I’m sure he didn’t want his children to grow up thinking that flying by reindeer was a legitimate mode of transportation.

I wonder how much Tolkien actually cared that his children literally “believed” in his Father Christmas letters. I doubt that his point was to make them think that the letters were literally true. Maybe some parents in our shallow culture might be mislead by the cultural pressure into thinking that their children are missing out on something if they don’t literally believe in Santa. However, I’m willing to bet that most parents aren’t trying to convince their children that Santa is literally true. They certainly don’t expect or desire their children to believe that Santa is literally true forever. Rather, they want their children’s belief in Santa to mature into wisdom and creativity and a better understanding of non-literal truth.

I’ll outsource my initial reaction to the potoo bird, if this comments section is up to posting pics:

<a href=”http://s1308.photobucket.com/user/kyndrian/media/potoobirdwat_zps59839b54.jpg.html” target=”_blank”><img src=”http://i1308.photobucket.com/albums/s612/kyndrian/potoobirdwat_zps59839b54.jpg” border=”0″ alt=” photo potoobirdwat_zps59839b54.jpg”/></a>

That is some unwieldy black-and-white thinking there. Would you say that parents are lying to their children when they read fairy tales without a three-point lecture about how fairies aren’t real?

It’s subjects like this when I think the pragmatic test has some merit. Did Tolkien’s children come to any harm, mentally or emotionally? I have seen no evidence to support that, so until I come upon evidence to the contrary, I feel safe in assuming that Tolkien handled it well and the children didn’t come to any harm. Do we have to do exactly what Tolkien did? No. I’d say it mostly depends on the child. Are we dealing with a literal-minded kid (like my Dad probably was) or a kid who is comfortable with make-believe?

Okay, the link didn’t work. Let’s try again, because I’m cheaply amused by this pic: http://i1308.photobucket.com/albums/s612/kyndrian/potoobirdwat_zps59839b54.jpg

The Santa Deception Tradition doesn’t count as a make-believe game or fairy tale. Make-believe games are pretend play, and fairy tales happen long ago and far away. With Santa, however, parents engage in a concerted and comprehensive campaign to convince their children that yes, Santa is real, to the point of writing complex correspondence on his behalf as Tolkien did, with tongue firmly not planted in cheek. The deception is elaborate — from the Santa-saturated pop culture of Christmas, to the empty cookie plates and exclamations of fake surprise at the presents on Christmas morning. All to perpetuate an illusion when the real Reason for the Season (my apologies for the use of such a clichéd phrase) is imbued with far deeper magic than Santa could ever hope to mimic.

I understand your point in regard to pragmatism, notleia, but I think it speaks to a deeper problem with the pro-Santa Deception Tradition argument, at least inasmuch as I’ve encountered it. The problem I speak of is the tendency of Santa advocates to defend the Deception Tradition by challenging all comers to tell them what’s wrong with it. But that argument is insufficient. I can tell you easily what’s wrong with it: it’s a lie, by any definition of the word. What I’m more concerned with is what’s right with it. What’s so important, so valuable, so indispensable about the Santa Deception Tradition that we all have to ignore the fact that it requires parents to deliberately lie to their children?

You were one of those literal-minded kids, weren’t you.

I was one of those literal-minded kids, and I was also a natural skeptic. My grandmother tried to get us kids to believe in Santa while my mom, who wanted to be truthful, downplayed it though she never actually contradicted my grandmother. Finally, when I was about 4 yrs old, I took a hard look at the issue and asked Mom if all these Santa stories were true. My stumbling block: how could anyone could possibly come down everyone’s chimney all over the world simultaneously at midnight? When I asked Mom about it one night when she was putting me to bed, she gave me the old “Santa is the spirit of Christmas” non-answer. “Okay,” I said after trying but failing to make reconcile her explanation with the stories, “he’s not real. That’s what I thought, but I just wanted to make sure.”

I’m not a fiction-hater, but I definitely do believe it’s wrong to deliberately lie to our children about Santa or anything else. I don’t know if Tolkien’s kids knew all that was fabrication and played along with it to humor old Dad, or if they were truly deceived. If the deception was real, then I believe he was in error. If everyone was in on it, then it was just good plain fun, and I’m all for that.

You betcha I was and am a literal-minded kid. Didn’t stop me from becoming a fiction lover or from reading The Lord of the Rings nine times before I was fourteen. Didn’t stop me from drawing Christmas cards which featured Legolas standing guard by the sleigh while Santa cleared the chimney. Didn’t stop me from absorbing formative conceptions of “festive comfort” from lavishly-illustrated coffee-table explorations of Santa’s North Pole HQ. Doesn’t stop me from imagining Elrond’s Last Homely House after that selfsame pattern. Doesn’t stop the chills from sliding down my spine whenever I watch the titular character advance into those silent woods on top of the world in The Snowman. Doesn’t stop me from enjoying Santa Claus, the fictional character, as a figure who embodies everything that makes the Christmas season feel so merry and bright.

But I have found that it helps me see straight through a slew of deceptions whose sole basis is sentimentality.

You may have just clarified something huge for me.

See, in my story the Santa deception/legend/pretend/whatever was not merely sentimental. It was “sold” to me as much more of a “high” myth than many people treat it. That’s why my prevailing memories of the Santa story are not sentimental silliness, but God-glorifying expectation and wonder.

I think you may have misunderstood me. My point was that, while the meaning and imagery associated with Santa is about as “high myth” as it gets (hence my recitation of perceptual bonafides), the tradition of pretending that he’s a real live person seems based entirely upon sentimentality, regardless of any “What Would Tolkien Do?” justifications.

I guess I missed the context of your argument. I agree that I can’t really defend the “Santa is literally and factually true” approach when I don’t see that it really makes it any more fun than the “Santa is a fun story” approach. Still, I don’t think that it rips the fun and joy from Tolkien’s letters that they really aren’t from Father Christmas. The kids could have found out/known already that they came from Dad but didn’t mind because it was still fun.

And I totally want a Christmas card with Legolas as Santa’s helper. Somebody with better Photoshop skills than I have should make that a thing.

I want to see a Christmas card where Legolas says that what he really wants is to be a dentist.

No dentistry involved, but here:

https://www.dropbox.com/s/p49k42q7lwh41rf/santa%26legolas.jpg

To me, the reason for not lying to children is not because it might lead them to reject Christianity or hate God – but simply that you shouldn’t lie to children (or anyone else).

This, however, does not mean that I fall into any of the other options given:

Children can enjoy Santa without having to believe he’s true. I did. (I still do!)

I never thought Santa was real–not that my parents took a hard stand one way or another, but I never thought he was real. I knew perfectly well that the things in my stockings or labeled “Santa” were my parents’ way of getting around their three-presents per person rule, which was rather flexible anyway.

And as an adult, I feel that there are much more interesting stories to tell anyway. Tiny elves who make presents? Boring. Full, human-sized elves who have complicated genealogies and a tendency to in-fighting? Bring it on.

I wrote letters to Santa once, maybe twice, three times at the absolute most. My parents decided fairly early to drop the whole Santa thing. I’ve pondered the idea of incorporating Santa more in my own children’s Christmas — a purely theoretical exercise at this point — but i’ve never been able to think of a good reason to include him, at least beyond an examination into the original St. Nicholas.

I’m not afraid of them not believing in Jesus because Santa didn’t turn out to be real, and i don’t think that someone who has their kids believe in Santa is “abusing” them or anything crazy like that. I just don’t think i missed anything by not growing up believing in Santa Claus, and i don’t see what my children would gain by believing in Santa Claus.

My kids loved reading the collected Tolkien “Letters from Father Christmas..”

My children were raised to believe the truth – that he is real, and that he is St. Nicholas, a real person who is a saint and is in Heaven, close to God, and very aware and interested in what we do on earth. He has a special interest in the Feast of the Nativity because as a bishop in the Church, he began the practice of Christians giving gifts to children as a sign of charity and love for one another, and that he fed and gave alms to the poor, which we should also do. (This is a good time to tell them the story of Good King (Saint) Wenceslas.) We tell stories about “Father Christmas” or “Santa Claus,” who are based on him, and that’s who the man in the red suit in the songs and movies and the TV show about Rudolph is, or who makes an appearance in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.” That Santa Claus or Father Christmas is a figure we use to symbolize the spirit of the season. It’s fun to tell stories about him and all the things he does, but when we give or receive gifts, to family or friends or the poor, we do that because we like to honor the birth of the Christ-Child in a lot of different ways, especially by showing love and charity, as the Wise Men also did, and that we are doing that in the same spirit that St. Nicholas did. When we give gifts to the poor, we are actually giving them to Christ himself, as Jesus taught us. If other children believe that Santa brings them gifts himself, that’s fine and a fun way to celebrate the season, and you should never hurt their feelings or make them feel bad by telling them otherwise.

That worked pretty well for us.

Tolkien’s letters are charming, of course – they grow progressively more elaborate each year as the cast of characters grow, there are codes and ciphers (of course), adventures, snow men and mischievous polar bears, battles with goblins, etc. What child would NOT have enjoyed receiving such letters, from a talent like Tolkien, or being invited to enter into a fantasy world?

The issue of whether creating a fantasy for the enjoyment of others is “lying” is problematic. Christians frequently have to make decisions on whether any number of circumstances allow the telling of a falsehood.

Should the Catholic and Evangelical Lutherans who saved nearly a million Jews from the Nazis have told the truth when the Gestapo demanded to know if anyone is hiding in the basement, or whether a baptismal certificate is valid?

Should a Christian undercover police officer, CIA field officer, or FBI agent pose as someone he is not when investigating meth dealers, al-Qaeda terrorists, or on-line child molesters and pornographers?

Should pro-life Christian groups, such as the one headed by Lila Rose, pretend to be someone they are not to gather information on the practices of abortion mills?

Does a writer who writes a piece of fiction that is not clearly labelled as such commit a falsehood? Or an actor on film or stage who pretends to be a character? Is a listing of their true name in the program or credits count, or should they be required to tug off their false beard at the beginning of an act and say, “I’m not really Hamlet, I’m Ed Witherspoon!”

Do kids playing Cowboys or Soldiers lie when they pretend to be someone they aren’t?

Is telling a joke a lie – “Three men walk into a bar…” Do you have to preface this by saying “This didn’t really happen!”

If your spouse asks you if he/she is looking older, is it a lie to answer in a way that protects his/her feelings?

Is telling a parable a lie, if the preacher (or Messiah) doesn’t first say “Hey, this is just a parable – it’s not really true!” a lie?

There’s a Jewish parable about parable I’ve always liked: Truth wandered naked into a town on a cold, freezing night. Because she was naked, and cold, and stark, she frightened everyone who opened a door when Truth knocked and they refused her entrance. At last, Truth came to the door of Parable, who welcomed her in and wrapped her in her own warm, golden garment. Thus arrayed, Truth returned to the other homes in the town, and wrapped in the golden robes of Parable, Truth was welcomed into every home.

We must also question to what degree Tolkien’s children believed in the literal truth of what he was saying, and to what extent they took enormous pleasure in joining in a shared fantasy tradition he created for his children. From their responses to Fr, Christmas in the book (reading between the lines in his replies to their questions), I would say the latter.

I’m not sure to what degree even young children actually believe in the modern Santa Claus mythos. Children are able to accept elements of a fantasy world to some degree while accepting the “real” world, a capacity that seems to lessen as they grow older. I was told about Santa by my parents, but at a very young age didn’t really believe that Santa delivered gifts. I think I accepted it as a kind of shared joke that we all agreed to acknowledge, and which made the season more fun. (We didn’t have a chimney, for one thing. I couldn’t picture Santa squeezing through the heater ductwork.)

I feel my approach is probably better than teaching that Santa comes into everyone’s house, but would argue that a parent inviting his or her young child into a fantasy world about Santa Claus, as a way to teach deeper truths about love and charity and the real reason for Christmas, is acceptable and is not a lie, but rather a parabolic story. Others may differ.

I don’t think every make-believe story needs to be faced with ‘this isn’t true’. The problem is when people say ‘this is true’ – and sometimes go to elaborate lengths to ‘prove it.

Jesus told make believe stories, sure. But if he had tried to convince people they were true, maybe faked some documents to prove it…

I don’t think every make-believe story needs to be faced with ‘this isn’t true’. The problem is when people say ‘this is true’ – and sometimes go to elaborate lengths to ‘prove it.

I agree with you. I’ve known families who went to extraordinary lengths to convince their children that Santa Claus visited their house – faked bootprints on the roof, etc. When one goes to those lengths to perpetuate a hoax, one shouldn’t be surprised that it’s hard to deprogram their son. One of my daughter’s friends still believed at age 11, which is a little long in the tooth. (Or, she had a very dry sense of humor and was just yanking her mom’s chain as payback.)

I don’t think Tolkien’s letters were the same thing, however, and as his children matured, they obviously still treasured the letters. My younger kids still like to toss out oatmeal in the back yard for Santa’s reindeer (the Mexican-American kids in the neighborhood where I grew up did the same thing with lettuce for the Magi’s camels), despite not believing in Clement Moore and Thomas Nast’s conception of Santa Claus (especially not Thomas Nast’s Santa Claus… The man was quite the anti-Irish bigot.) These kind of play customs can be a fun shared mythos (or a “High Myth,” as E. Stephen said), not a falsehood. (And the oatmeal and lettuce always gets eaten by morning, so who knows…)

Jesus told make believe stories, sure. But if he had tried to convince people they were true, maybe faked some documents to prove it…

Sure. Obviously, there are some gradations on whether we consider a story, a parable, a role, or an elaborate shared mythos as a “lie,” and not everyone will agree on where the boundaries lie. That’s as it should be. I suspect that Jesus will not judge the Santaists too harshly.

Ha ha, at first I read “Jesus will not judge the *Satanists* too harshly.”

Now think I’ll change my Facebook status to, “I didn’t grow up a Santaist, but now I find myself having fun with the idea,” and see how many concerned/angry/bewildered comments I get.

I know someone who, feeling her son is a bit old for Santa, has tried to tell him it’s not true. He’s totally unconvinced by her debunking, though!

In our house Santa comes in the skylight and down the loft ladder!

I guess I would ask why during the time of Christmas Tolkien’s thoughts were concerned with that. I mean, I know that it’s fun to make up a story to entertain kids, and that we can get lost in stories we make and build them up. But it’s not always the best time to concern ourselves with them.

Like it’s fun to read Christian science fiction, but you wonder about the person who reads it during the pastor’s sermon in church. It’s valuable to use older myths and proxies to explain the truth of Christianity, but there are times when we need to accept the reality of Christ without them. I don’t think this is all the time, but things like Christmas or church services are times where our propensity for using proxies or letting story explain truth subside and we should experience and encourage others to experience Christ directly.

Maybe I’m overreacting, but I’m not as keen on the amount of integrating we do with the default culture these days.

Oh, and I don’t really remember much of my thoughts on Santa as a child. Most of my memories of Christmas were materialistic. About the toys I had.

I’m not sure to what degree even young children actually believe in the modern Santa Claus mythos. Children are able to accept elements of a fantasy world to some degree while accepting the “real” world, a capacity that seems to lessen as they grow older.

This is where the myth works for me. Children crave fantasy and conspiracy. As the second eldest of 5 children I was instructed in myth keeping. I learned to hold another world next to my perception of the one in front of my nose and enjoy the benefits of both. Reality is always greater than the sum of its parts.

Tolkien knew. Why should children have all the fun?

Nostalgia Critic reference (he doesn’t swear in this one): http://thatguywiththeglasses.com/videolinks/thatguywiththeglasses/nostalgia-critic/41704-why-lie-to-kids-about-santa

Father Christmas is not the same as the American Santa/St Nicholas tradition. ‘Santa’ was relatively unknown in England before the 1970’s. The English Father Christmas is an anthropomorphic personification of Yule, like ‘Jack Frost’ is of icy weather. He also carries with him some Pagan remembrances of the Old English god Woden.

Santa has spread to England during the last 40 years o so mainly as a result of Americanisation and globalisation.

” He also carries with him some Pagan remembrances of the Old English god Woden.”

In what ways, Alex?