History as Fantasy: Netflix’s Barbarians Miniseries

This week’s post is a review of a miniseries on Netflix–Barbarians–what it’s about, how historic it happens to be, what I think is good and bad about it, and the significance of what it portrays beyond its supposed goal of capturing history. Generally, historical fiction is outside the realm of speculative fiction–but I think Barbarians takes history and in effect makes it into a fantasy tale, including even elements of magic.

Some spoilers of the plot of the miniseries will follow, though I will speak in generalities when possible.

Latin and German

Barbarians grabbed my attention from its opening scenes with a storytelling decision that I really enjoyed that may not matter much to most speculative fiction fans: the Romans spoke Latin, not Ecclesiastical or Church Latin, but Latin as linguists believe it was spoken 2000 years ago, with rolling Rs and Vs pronounced like the letter W in English. The series comes in dubbed versions–I’ll say more about that later on–but only the speech of the Barbarians is dubbed. All versions portray the Romans speaking Latin.

Some Latin-speakers riding in. Image copyright: Netflix.

I watched the original version, not a dubbed one, but with dialogue in subtitles (Spanish subtitles in the version I saw, actually). The miniseries was produced in Germany, though largely filmed in forests in Hungary, so the language the Barbarians speak in the original version is German. For a few minutes I had the illusion that even the German was supposed to represent a re-constructed ancient German. I thought so because of certain particular words. What in modern German would be “king” is KĂśnig, but in Barbarians is Reik, an older term. And the actors pronounce tribe names in a way I think better matches ancient pronunciation than modern. For example, the tribe of the Cherusci is consistently said as “Kheruska.”

But no, the German of the barbarians in Barbarians is in fact, modern German, without even any regional dialect from what my research on this topic turned up. In fact, my college German I studied more than twenty years ago kicked in more and more as I watched the series, to the degree that by episode six I understood most of the dialogue without referring to the subtitles–and my poor wife had to put up with me saying random things in German for a while.

So, other than reviving my German and pleasing my Latin-loving-language-and-history nerd self, what’s good about this series?

The Good and the Bad in Visual Details

One of the good things stems from small historical touches. Not only the use of Latin in correct pronunciation, but the clothing and uniforms and set design is all quite historical and interesting. I will say more about the historicity of the plot or lack thereof in another point, but in most small details, the miniseries gave an accurate view of what ancient times really looked like based on actual archaeology and known fact.

Germanic wooden building with thatched roof and dirt floors, large wooden barns and storerooms, plus glimpses of Rome, all were extremely historically accurate from what I know of the history. Roman uniforms, including some officers wearing breastplates with artistic musculature and metal masks shaped like a human face added to helmets are based on archeological findings. The Romans really did wear stuff like that–not all the uniforms were perfectly uniform. And German clothing–instead of showing them in animal skins or no clothing as per Conan the Barbarian, realistically showed people wearing simple clothing in natural colors, sometimes with simple plaid patters, as if hand-woven, which is certainly what the Germanic tribes would have worn.

Hairstyles I also saw as good at first. Romans are consistently shown as clean-shaven, with a pretty standard hairstyle. Germanic tribesmen and women are showing with a wide variety of hairstyles. Most of the women have long hair, but some have braids and some don’t. Some men have long hair, but some don’t. Some men have beards but others are clean-shaven. And at least one tribal leader is shown as having a shaved head.

I at first thought that was good because ancient Germans really did have the ability to cut and style hair and certainly did so. But…after a while the variety of hairstyles seemed unrealistic to me. Yeah, the technology to shave a head existed, but it wouldn’t be easy and there’s no evidence I know of that ancient Germans actually ever did routinely shave their heads. And I would expect the hairstyles to follow a tribal pattern, but they did not. In fact, overall, hairstyles simply reflected individual barbarians making individual choices, just as modern people would. I don’t think that’s an accident of how the story was told–it was done to make the Germanic tribes seem more like modern people, I think–but it wasn’t strictly historically accurate.

Another thing I was disappointed with was the actual battle scenes in episode 6. I read a film critic reviewer who complained episodes 1-5 dragged on long for him, but episode 6 was great. I in fact was hoping for some meticulous attention to detail showing how Romans fought versus how barbarians engaged in combat, but nope. The Romans mostly did not even try to hold formation at certain key moments, didn’t raise their shields when they would have (spears flying at them), and mostly swung a gladius (Roman short sword) instead of stabbing with it, which was what it was mainly designed to do.

I also found a particular moment of battlefield flames (Germanic warriors setting parts of a field full of Romans on fire) to make no sense, to even qualify as silly–unless we see the portrayal as a fantasy and not historical fiction. In fantasy you can create any number of concoctions that will burn like gasoline or diesel, especially when magic is involved. Historical reality limits you to what the peoples of the time actually would have had. And what did Germanic peoples have that would burn like crazy? Pretty much tree pitch, which would harden if not kept warm, and rendered fat, which also needed to be kept warm not to gell. Both of which have distinctive smells, are not all that easy to come by–oh, and also don’t burn just like gasoline.

So, if you’re expecting historical reality in the battle scenes, sorry, what Barbarians in fact delivers there is mostly fantasy. (On the other hand, if you’re expecting fantasy, maybe you’ll have a good time watching the battles.)

A Sketchy Plot Overview–OR an Overview of a Sketchy Plot

The actual history behind Barbarians centers around the defeat of a Roman army in the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. A coalition of Germanic tribes destroyed three Roman legions under the command of Publius Quinctilius Varus in A.D. 9. The history we have is entirely written from the Roman point of view–no Germanic versions survive, because the Germans were illiterate at this time. However, archeological digs around the German town of Kalkreise show additional information about the battle, beyond just what the Roman historians said.

The key aspects of the battle that the miniseries gets right relate to the Romans under Varus alienating Germanic peoples with wanton cruelty and excessive taxation. Barbarians also agrees with history that the primary person responsible for defeat of Varus was a Germanic tribesman who had been taken to Rome as a captive as a child and who had achieved Roman citizenship and a position of trust as an Equestrian (roughly like being knighted). This barbarian-turned-Roman-who-betrayed-Rome was named Arminius.

The Netflix series goes astray in that portrays Arminius as an adopted son of Varus, which could be true but history does not record it that way. History says Arminius was a commander of auxiliary troops (Germans who fought on the Roman side) and someone Varus saw as a friend. Also, the Roman account of the battle has it lasting for three days, during heavy rain, with a number of specific things happening that are not captured in the Netflix version. And the number of people involved in the battle was much higher than what Barbarians shows. Between 16,000-20,000 on each side in reality in contrast to a few hundred shown and a reference to Arminus having “500 friends” in a snippet of dialogue.

Arminius in Germanic clothing. Image copyright: Netflix.

Whether Arminius will betray his adopted Roman father or not as opposed to betraying his childhood friends and actual father (a Germanic Reik, a tribal king) is what the plot mostly focuses on. It also makes his friends very important to the tale, including a woman (Thusnelda) who winds up leading troops in battle, which history does not record.

I would have instead told the story from the point of view of how the plot was carried out and covered up and how the Germanic tribes in fact beat the Romans. There’s some of that in Barbarians, but the focus really is on Arminius’s decision and it takes him quite some time to make up his mind.

This personal focus winds up with a plot that’s more character-driven than combat or strategy-driven, which makes it seem to me more like the plot of a fantasy novel than reality, especially because it shows particular situations that no historical account records. Again, there’s no evidence Varus adopted Arminius as a son or that he even knew him in Rome at all.

A Look at Religion in Barbarians

Another element in Barbarians which is perhaps is more like fantasy than historical fiction, other than certain battlefield moments and combat in general, is the portrayal of the religion of the German tribes. Though you could say the miniseries is reporting what the Germanic people believed about their religion, I suppose. But I don’t think that’s the actual dynamic.

Because, in Barbarians, a female seerer has no-kidding contact with the gods in which she is portrayed as literally seeing the future by various means, while another woman pretends to have such contact. Several confrontations between the real seer and the fake one happen. If one overlooks the brief moments in which the miniseries actually shows the real seer observing the future, you might think this was an actual historical religious dispute of some kind. But that’s not how it’s actually shown–the real seer has genuine power in Barbarians. And even if we suppose demonic power supported the Pagan priestess in reality, we have no evidence to suggest even demons can genuinely see the future. So, that particular element is more like a fantasy story than any historical account.

Note historians know Woden was the chief Germanic god and corresponds to the Norse god Odin linguistically speaking. But nobody knows–it’s not recorded by history–if the legends of Woden were essentially the same as Odin’s. For example, was Woden one-eyed? As far as I know, that’s unknown. But this god is treated just as if he were Odin in Barbarians and Thor is referenced as well.

And…while many Germanic tribesmen and women are shown being not particularly religious, some are quite religious. Also all tend to reverence forests and nature…and if you know modern German people, a strong connection to nature is very common there. The German Green Party is quite powerful and a sense of connection to nature is definitely a part of modern German culture. So in fact, the Germanic people in Barbarians are portrayed as more modern than the Romans, who are not shown to care about nature at all. (In terms of religion, the Romans are like 20th Century modernists and the Germans are like 21st Century postmodernists.)

In fact, the Romans are not shown to be religious at all. In one scene, a German briefly makes fun of the Roman god Mars, but there’s no acknowledgement other than that moment that at least some Romans were also quite religious, though not yet Christian in A.D. 9, when Jesus of Nazareth was young.

I keep reporting the rise of modern neo-paganism in this forum and elsewhere but feel many Christian readers of Speculative Faith are unconcerned about this issue. But Barbarians in effect represents the religion of modern neo-pagans better than it does ancient Germanic religion…and portrays it as having real power. I don’t think this was deliberately done by the producers with the intent of trying to influence people towards neo-paganism, but rather because their views of ancient religion have been influenced by modern neo-pagan thoughts and practices. Because the process of much of modern culture reverting to a modern version of polytheism is already underway. FYI.

To rephrase what I just said for clarity, I suspect the producers of the miniseries were trying to be realistic about ancient religion. But their ideas about what was realistic in ancient times have been influenced by modern neo-paganism. Because it’s around, people, believe it or not.

Concerned With Right-Wing Extremism

I did a bit of research trying to uncover what the producers themselves said about their portrayal of the past and ran into several bits of data in which they discussed what was on their minds as they created the miniseries. One of their biggest concerns was how to tell this story without supporting right-wing extremists.

Because, the defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest has been seized on by German nationalists for hundreds of years as a defining moment in the history of Germany–the first time Germans formed an alliance against an enemy, eventually pointing to the unification of Germany. Yes, the Nazis liked to talk about Arminius and his superiority over the Romans, though Germans were celebrating him long before that, as with heroic statues such as the Hermanndenkmal. But because of the Nazis, Arminius hasn’t been mentioned in modern German history books post-World War II.

A nationalistic German monument to Arminius. Image credit: Hubert Berberich.

So the producers were wondering how they would avoid creating a tale that would be a rallying cry for modern Neo-Nazis, who are the main group today who talks about Arminius.

Part of how they did that was by casting the lead role of Arminius not as a typical blond “Aryan” male, but as a Germanic person who happens to be darker than average and who is not particularly tall. Arminius in fact looks like he really might be Roman in this miniseries.

Arminius also does not in fact rally all the Germanic tribes very well. Some join him, yes, but many of those who do are not committed to unity in any way, including one of the key characters in the tale. So there’s not much to celebrate in the way of German unity in the way this story is told.

A Dash of Generational War?

Though the fact the producers say they did not want to support the vision of right-wingers says something about them. They themselves are from the point of view of modern people comfortably safe from extremism, which probably means they’re at least a bit left-leaning.

And there’s in my mind a clear non-right-wing way to interpret this story. The clean-shaven conservative Romans could be seen as representing the old-fashioned past from the point of view of modern culture, the stalwarts of the 20th Century. While the younger, more individualistic, more tattooed and more modern Pagan-nature-worshipping Germanic tribespeople could be seen as a rebellion of the youth against the old guard. In fact, only one of the Germanic kings or chiefs is shown to be older than around 30 or so, Arminius’s father. The rest seem quite young, certainly younger than Varus, who is the oldest figure in the main cast, followed in age by Segestes, a German supporter of the Romans. While all the rebels are young.

Certainly rebellions are often led by young people, but I think what is known about the historic past would suggest tribal leaders were older, proven warriors. Young leaders did come into power sometimes, but was the exception, not the rule.

Sympathy for the German Barbarians

Seeing a hint of generational war in Barbarians is of course an interpretation of how the story could be taken, not now the miniseries clearly is. Note though the story clearly does intend for the audience to root for the Germans and not for the Romans.

Only the Romans are shown to be cruel in the beginning of the tale. And as slavers. Certainly Romans were cruel and kept slaves, but Germanic tribesmen were not exactly nice-nice and they had slavery, too. In fact, the story shows Germanic cruelty, but not until the aftermath of the battle, which makes it seem like mere retaliation for past injustice rather than something that was a negative characteristic of Germanic culture. And no hint is dropped that ancient Germans kept slaves.

Note that the dialogue of the Germans comes in various dubbed versions, English, French, Spanish, etc. But the dialogue of the Romans is never dubbed. It’s always in the original Latin, representing a time long past and a people not our own. Clearly, we are intended to see the Germans as ourselves, no matter what our language is. And the Romans as foreign oppressors.

Conclusion

Clearly I found this miniseries worth some critical analysis. In that sense it was interesting to me. But did I like it? Do I recommend it?

I think a lot of people might agree with the reviewer who got bored with the first five episodes but thought the sixth was awesome.

I was the opposite. I was interested in the storytelling and the degree of historicity of the first five episodes, but felt the battle scenes missed key details by deviating from history, by showing Roman tactics incorrectly–plus some magic fire a-la Game of Thrones and some other moments I thought were silly. Plus the post-combat cruelty I did not enjoy.

**Note this series contains some nudity and sexuality, though limited, in addition to graphic violence. The violence was at its worst in the last episode but happened throughout the miniseries. For many people this miniseries wouldn’t be worth watching at all because of these negative elements.

Latin-loving nerds might really like it though. Just don’t expect real history beyond that and the costume design and architecture. Certain key details were spot on, but overall, Barbarians is a fantasy story, with an apparent cultural axe to grind, not a genuine look at history of the past.

Has anyone else seen Barbarians? Or similar historical series like Vikings or The Last Kingdom? If so, what are your thoughts about these series and their relationship with fantasy fiction?

None of these developments would have been possible without those early efforts to bring speculative fiction to TV and film, including some “soft speculation” such as a movie like The Shaggy Dog (Disney, 1959).

None of these developments would have been possible without those early efforts to bring speculative fiction to TV and film, including some “soft speculation” such as a movie like The Shaggy Dog (Disney, 1959).

So it is, I think, with a story. A poem about a rose doesn’t need to mention God in order to bring glory to God.

So it is, I think, with a story. A poem about a rose doesn’t need to mention God in order to bring glory to God. How do Christians thank God for stories?

How do Christians thank God for stories?

In many respects, we’re witnessing in the US the change in the Thanksgiving Day celebration from a major holiday to a minor one. The presence of Thanksgiving or harvest day celebrations seem more apt to be important to a culture if the people are in tune with the growth cycle. As our urban society has become divorced from the way food gets to our table, we seem less thankful and more inclined to take for granted the food we eat.

In many respects, we’re witnessing in the US the change in the Thanksgiving Day celebration from a major holiday to a minor one. The presence of Thanksgiving or harvest day celebrations seem more apt to be important to a culture if the people are in tune with the growth cycle. As our urban society has become divorced from the way food gets to our table, we seem less thankful and more inclined to take for granted the food we eat. On the other hand, if these futuristic societies are a return to a more agrarian way of life or if the world of an epic fantasy has a rural setting in which people are dependent upon cultivating the soil and growing their own food, then perhaps a harvest festival would be appropriate.

On the other hand, if these futuristic societies are a return to a more agrarian way of life or if the world of an epic fantasy has a rural setting in which people are dependent upon cultivating the soil and growing their own food, then perhaps a harvest festival would be appropriate.

bygone days of the 1980âs, poor ALF would have never made it past season one with his desire to eat cats, particularly when he tried to microwave the cat for a fast meal.

bygone days of the 1980âs, poor ALF would have never made it past season one with his desire to eat cats, particularly when he tried to microwave the cat for a fast meal.  mere observers of our fanaticism, but those who immerse themselves in the obsession. We connect to the source of our fandom on many levels, but the one that makes us all fans is imagination. I don’t mind getting into rigorous discussion of why Captain James T. Kirk is the best captain of all time. I’ll go toe to toe with you defending the position that Vulcan should never have been destroyed in the reboot of the franchise. I’ll sign the change dot org petition to produce an episode showing a battle between the Voth and Species 8472.

mere observers of our fanaticism, but those who immerse themselves in the obsession. We connect to the source of our fandom on many levels, but the one that makes us all fans is imagination. I don’t mind getting into rigorous discussion of why Captain James T. Kirk is the best captain of all time. I’ll go toe to toe with you defending the position that Vulcan should never have been destroyed in the reboot of the franchise. I’ll sign the change dot org petition to produce an episode showing a battle between the Voth and Species 8472.

Centuries before, the prophet Jonah, on the third day of his ordeal in the stomach of a great fish, prayed

Centuries before, the prophet Jonah, on the third day of his ordeal in the stomach of a great fish, prayed

More recently I’ve enjoyed Kay Marshall Strom’s novels such as The Call of Zulina, set in Africa, or The Faith of Ashish, set in India, both in an earlier century. Or there are novels such as Jill Stengl’s Shadows of Yesterday (Until That Distant Day Book 1), a novel set in France during the early days of the republic.

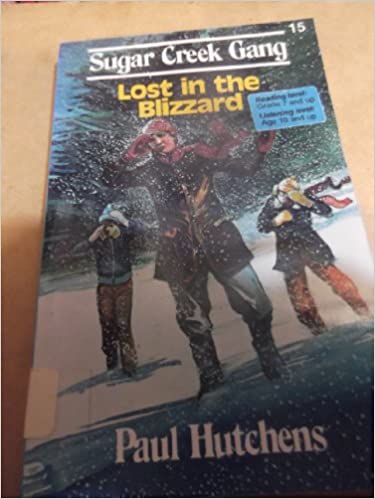

More recently I’ve enjoyed Kay Marshall Strom’s novels such as The Call of Zulina, set in Africa, or The Faith of Ashish, set in India, both in an earlier century. Or there are novels such as Jill Stengl’s Shadows of Yesterday (Until That Distant Day Book 1), a novel set in France during the early days of the republic. Other books that my brother owned but were also included in our family reading were ones by Paul Hutchens. The Sugar Creek Gang books “follow the legendary escapades of Bill Collins, Dragonfly, and the rest of the gang as they struggle with the application of their Christian faith to the adventure of life.”

Other books that my brother owned but were also included in our family reading were ones by Paul Hutchens. The Sugar Creek Gang books “follow the legendary escapades of Bill Collins, Dragonfly, and the rest of the gang as they struggle with the application of their Christian faith to the adventure of life.”