Science Saving the Bible from Theologians

The title is more an attention-grabber than the most accurate way to say what I really mean. More accurate would have been something like this: “Contrary to what you might expect, some of the biggest doubters of the Bible are theologians and doctors of divinity–yes, of course of the liberal sort who engage in “higher criticism”–while some of the evidence backing up the chronology of the Bible against these naysayers comes from straight from scientific data, in particular studies of linguistics and archaelogy.” But that’s not as catchy as: “Science Saving the Bible from Theologians.”

I expect that many Christians who are speculative fiction fans will not be especially aware of this particular issue. IF science hits our radar, it will be for those of us who are science fiction fans–we might follow debates over the origin of the universe, in which atheist scientists critize the idea God exists supposedly based on what’s known from science, a criticism we may feel the need to answer (I wrote a series answering atheists, in fact). Or we might think about the likelihood of aliens existing and how that might relate to our understanding of God (I wrote a series about what aliens teach us about God, too). Or, how Christian writers might choose to employ aliens in stories, in spite of some Christians objecting to the existence of aliens at all–objecting based on the idea that writing aliens would be caving in to evolutionary science (sorry, no series on that, just an article).

We see in the examples above that science and relgious belief seem to be at odds. Science pointing one way, Bible believers another. (Though of course my articles above treat science seriously and while I disagree with atheist assumptions, I don’t disagree with the validity of science itself.) But science and belief are not at odds everywhere–as this article is pointing out.

Note this article cannot possibly cover all the instances of where science has in effect wound up defending the Bible verses a type of academic scholarship that sees it as late and non-literal. But it will highlight some particular issues: The dating and authenticity of the Pentateuch (first 5 books), of Isaiah, and John’s Gospel.

The debates over the origin and nature of the Bible may not be on our radar as much, because the topic doesn’t have as direct a connection to speculative stories. Thought the topic does have some connection to such stories–the question of “What was the world really like in Bible times?” can have a speculative element, especially if we choose to include time-travel to Bible lands via fantastical tales.

So I’m highlighting the nature of this debate, pointing out how science can serve serve as a defender of traditional views of the Bible, even though that’s not normally how we think of science interatcting with Biblical Studies.

The Academic Consensus On Bible Chronology

Traditional Chronology

Not all Speculative Faith readers may not be aware of it, but the vast majority of academics in Biblical Studies do not hold to what we might call the traditional view of Bible chronology (though of course some scholars defend this view). The traditional view would be that Moses wrote the first five books of the Bible, then each book after that was written more or less at the time in which it was set. So the book of Joshua would have been written right after Deuteronomy, Jonah would have been written by Jonah after the events the book describes, Isaiah would have been written by the prophet Isaiah, etc.

The traditional chronology would of course date books set during the Persian Empire, like Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, much later than Genesis, with books like Kings being written somewhere in between. In New Testament chronology, the traditional view was Matthew was written first and Revelation last (though the epistles are not in chronological order), all complete by the end of the First Century A.D.

Late 19th Century Chronology

By the late 1800s, the spirit of the age (Zeitgeist) in academic circles was not in favor of seeing the Bible as anything special, especially in terms of its decription of origins. The origin of the universe had been explained long ago in Greek philosophy by the idea the universe had always existed and even if one granted that it came into being at one point, scientist and mathematician Ludwig Boltzmann taught that it could come about as the result of random fluctations, given enough time (Bolzmann’s idea is disproven by the thought exercise of what’s called a Boltzmann Brain–a “universe” self-generating by random fluctuations would more easily produce a single mind than a universe). Couple the notion of an already-existing or already-explained universe with known laws of physics and moreover Darwinism, and then literally everything was believed to be explicable in non-miraculous terms.

Given that philosophy, it was only a matter of time before a dose of skeptical treatment about its origins would become the standard way to see the Bible. Even though the philosopher Spinoza doubted Moses authored the Pentateuch and Jean Astruc speculated the authorship of Bible passages could be determined by the name of God used and Johann Karl Wilhelm Vatke argued for evolution of relgion in the Bible, it’s Julius Wellhausen who is generally credited with creating the definitive academic hypothesis which convinced most scholars that Moses did not write the first five books of the Bible. That hypothesis is known as the Documentary Hyptothesis.

The Documentary Hypothesis, which dominated the academic consensus on the Pentateuch, held that modern critical scholars can detect the layers of writing of the Bible by the names of God used. First, there was a writer who liked to use the word “Jehovah” (יחוח), followed by one who liked to write “God” (as in “Elohim”–אלוהים), followed by the writer of Deuteronomy, followed by a writer who was interested in customs of priests. These separate sources or “documents” were designated “J” for Jehovah, “E” for the Elohist, “D” for the writer of Deuteronomy, and “P” for the priestly writer. The earliest of these texts was seen to be written around the time of King Solomon and the latest, during the Persian Era.

Likewise when looking at the book of Isaiah, the late 19th Century view was that it was fragmentary, the work of two or maybe three authors, largely but not exclusively between differences in theme in Isaiah 1-39, 40-55, and 56-66. Not based on any discoveries of ancient texts, but rather a presumption that the message of the latter part of the book had historical references and spiritual themes that could not have come from an earlier time, when Isaiah would have lived. Naturally, the question was eventually asked if Isaiah was a historical person at all. (40-66 was generally dated to the Persian period, long after any historical Isaiah would have lived.)

Q not Q!

(Copyright Paramount)

The Gospels also were treated to a documentary view. Mark was seen as original and Mark and Luke copied from it. But instead of seeing Luke referring to both Mark and Matthew and other unnamed sources, scholarship invented a source called “Q” that both Matthew and Luke had independently drawn from in addition to Matthew. There was controversy over the book of John, but it increasingly was seen as unhistorical, a product of evolution of religious thought of Christianity, much later than the other Gospels (some claims had it that John could not have been written any earlier than the end of the 2nd Century, though the 3rd or 4th Centuries were favored by some).

20th-21st Century Chronology

The dating of the Gospel of John underwent a radical shift with the discovery and 1934 publication concerning of a scrap of papyrus, the ancient Egyptian paper pressed together from reeds. P52 contains a small portion of John’s Gospel and is widely seen as the oldest fragment of any Biblical text, in terms of time-of-writing-to-copy-we-have. The original date of the fragment, based on handwriting style, was A.D. 100 to 150. In recent years, this date has been challenged by some to be possibly as late as the 3rd Century, but with plurality of scholars accepting a date of A.D. 125-175. Note though that the fragment comes from Egypt. Presumably John’s Gospel would have already existed for decades prior to being found on an Egyptian papyrus, which strongly implies a First Century date for John.

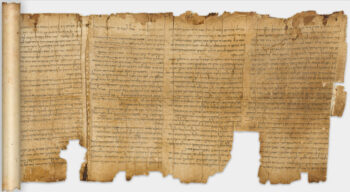

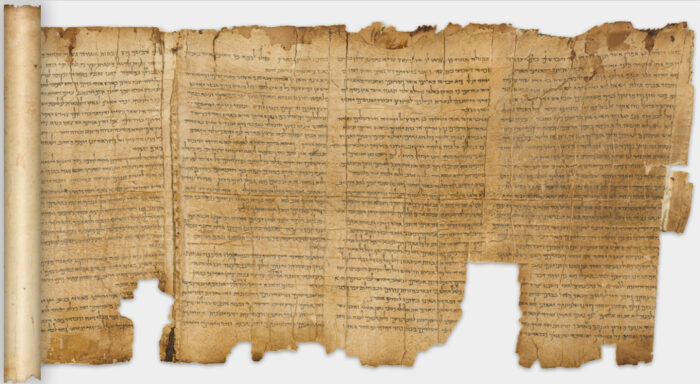

The concept of a Deutero-Isaiah or even a third Isaiah is still with us in the modern consensus opinion of Isaiah, in spite of the discovery of the Dead Seas Scrolls (DSS), first published in 1947. Why would the DSS affect a scholarly view of Isaiah? Because the first whole scroll of a Bible book found among the DSS, and the one to this day which is most complete, is a copy of Isaiah, with all the chapters we know combined into one book, just the way we have it. Over a thousand years older than any other copies of Isaiah anyone ever had. Clearly if there was a complilation of multiple authors of Isaiah, it happened hundreds of years before the DSS were tucked away into their caves.

Isaiah chapter 1 in the DSS. Courtesy: The Israel Museum

In the late 2oth Century and early 21st Century, the Documentary Hyptothesis is still followed by some people, but has largely been replaced by the Supplementary Hypothesis and similar concepts–which dates the Pentateuch even later than the Documentary Hyptothesis, making Deuteronomy the first book written and all other parts of the first five Biblical books coming from the period of the Babylonian exile and the Persian period. (In fact, some modern Higher Critics date all or almost all the Hebrew Bible from the Persian period.)

Science to the Rescue (well, sort of…)

Archeology

I’ve already mentioned how P52 changed the view of the Gospel of John. Let’s talk a bit about the modern re-interpretation of the archeological discovery of P52 by a minority of scholars. The minority view that P52 is possibly as late as the Third Century is a 21st Century claim that I personally am not able to evaluate–I can’t myself identify the details of Greek letter-forming style by time period, even though I’ve looked into this topic a little bit. But I can’t help but notice that atheists, fans of the religious-evolution-of-Christianity idea, and other general doubters of the authenticity of John (such as a Muslim site I’m linking here) have embraced the later dating…whereas more neutral observers have not. Science, as in people objectively looking at the available data and determining what it indicates, still leans in favor of P52 being the oldest flash-to-bang of any Bible text. In spite of controversial claims otherwise, the available science still seems to back up the idea that John comes from the First Century, based on P52.

Likewise I’ve talked about how the DSS shows that Isaiah was seen as a unified book around the 2nd Century B.C. (a likely date for the Isaiah scroll in the caves of Qumran). However, I didn’t mention the discovery of seals that provide historical evidence (via the science of archeology) that Isaiah was an actual person, a contemporary of King Hezekiah, as talked about in this 2018 National Geographic article.

Yeah, just because this bit of a seal that seems to say “Belonging to Isaiah the Prophet” is from the right time period as the Biblical Isaiah and was found less than ten feet away from a find with King Hezekiah’s name on it, doesn’t completely prove it was the same Isaiah as the one mentioned in the Bible. And of course it doesn’t prove who wrote the book of Isaiah. But as these discoveries are made, over and over, people mentioned in the Bible who were once considered legendary or doubtful are discovered to have existed. Or at least, there are very ancient references to the people which really seem to indicate they existed. (Another example: the Tel Dan archeological find referencing King David, found in 1993.)

In all of this, actual scientific findings continue to chip away at ideas that stemmed from hypotheses on the evolution of religion and how thematic changes in the Bible and differing word uses required different authors. That is, facts are eroding hypothetical notions of whether or not the Bible is reliable. One drip of scientific data at a time, moving incrementally in the direction of science supporting the chronology and authenticity of Bible texts.

Linguistics

The study of the Hebrew Bible by linguists has long yielded two basic layers of Hebrew in the Bible. The first is Early Biblical (or Early Classical) and Late Biblical Hebrew. Unlike handwriting analysis of ancient Greek by time periods, this is a subject I have personal knowledge of.

It turns out that Early Biblical Hebrew matches those inscriptions and fragments from pottery that are available in the time before the 6th Century B.C., that is, before the Babylonian exile. While Late Biblical Hebrew, which has changes in vocabulary including Persian and Aramaic loan words, a number of spelling and grammar changes, dates from the time after the Babylonian exile/the Persian period. And, linguistic analysis repeatedly shows that the Pentateuch, all of it, belongs to the Early type of Hebrew. Books like Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel, and Esther, are, surprise, surprise, late Hebrew.

Books fall in line, generally speaking, with the time period they are portrayed to have been written. There are a few exceptions to this–for example, the Song of Solomon has a number of linguistic late features (which doesn’t really prove it wasn’t written in the time of Solomon at all, because it could have been re-written later, as a sort of NIV update of the original work).

Oh, and Isaiah, which once was thought to have a significant separation of time between the latter half of the book and the former? It’s Early Hebrew. The whole thing. And while that doesn’t prove the same author wrote the whole thing, linguistics does damage to ideas about the second half being a lot later.

Note there have been challenges to the liguistic data, mostly arising from theologians. This topic is a matter of debate to a degree, with (let it be fairly said) some linguists arguing that the differences in early and late Hebrew could reflect stylistic choices and scribes deliberately faking the style of the past in places…in effect arguing that all Biblical Hebrew comes from the Post-Exilic period, with “early” Hebrew being a stylistic choice or an expertly-crafted fake.

The linguists-who-support-the-Hebrew-Bible-is-all-late also point out that while Aramaic words are much more common in Late Biblical Hebrew, they also exist in Early Biblical Hebrew…though science answers this, too, with discoveries that show Aramaic was a key language in the region starting around 1000 B.C., and existed as a language long before the first written texts which have been found in Aramaic, which are from around 3,100 years ago (1,100 B.C.). So it isn’t surprising that Early Hebrew would have some Aramaicisms, though Late Hebrew would have more, and it certainly doesn’t prove the entire Hebrew Bible was written after the Babylonian Exile.

Personally, I’m much more used to Early Biblical Hebrew and so find Late Biblical Hebrew more difficult to read…and I also find the idea that all Hebrew represents one time period a bit silly. All languages change over time–the simplest and clearest explanation of the differences evident in the Hebrew Bible is it changed over time, too. And, an examination of those changes argue that Bible books of the Old Testament are more or less written in the time period the Bible claims they come from, with very few exceptions.

Conclusion

There are many more discoveries that could be added to the list of things that chip away at views first made widespread in the late 1800s and only modified somewhat by the majority of higher critics of the 20th and 21st Centuries. But I’ve shared enough to get the idea across.

In Biblical Studies, on a regular basis science is giving support to traditional views of Bible chronology and authenticity. No, it isn’t true that the linguists and archeologists can prove their points absolutely, and it isn’t true they are all in complete agreement. But the other side, the ones who make claims that exclude Biblical authenticity, which make the whole Bible later-than-we-think, which show a clear evolution of religious ideas in a way that doesn’t match the written order of Bible books, they’re the ones using analogy and looking into style–that is, engaging in highly speculative stuff, but treating their speculations as if they were reality. It was called the Documentary Hyptothesis for a reason–it was a hypothesis, though for nearly a century it was treated as a fact in the most elevated academic circles.

Romans 3:4 says, “Let God be true and every man a liar.” But not all humans are liars–some are going to follow what the evidence shows…and the archeology and linguistics indicate something quite different from what liberal theologians and Divinity students say.

What are your thoughts on this topic? Are there any bits of archaelogy you find especially interesting that you’d like to share? Any counter-points to make? Please comment below.

Here’s the part where I name-drop my favorite dude on this weird, granular theological stuff: https://isthatinthebible.wordpress.com/ He is my kind of nerd. I personally find it fascinating to trace the development of the gospels, including the Q source and also Marcion’s Evangelion (tho most of my amusement comes from making anime jokes about Evangelion).

Off-topic: I read that Texas’s National Guard is being mobilized to

stack COVID corpses in refrigerated trailersuhhh….support the overwhelmed hospitals. Have you been called up, Travis?The long-believed view of the development of the Gospels is of course not the simplest way to tell the story of how the Gospels came to be. I’ve got a simpler method, let’s see if you can answer it.

Mark, someone with rather peripheral connections to Christ (he probably was the young man who ran naked in Mark 14:51-52), for whatever reason decided to write what he knew of Christ in book form. Probably as an evangelism tool (the story hadn’t been written prior to Mark because of the common expectation of Jesus’s immanent return).

Matthew got a copy of Mark’s Gospel and was all like, “This is pretty good, but there’s a lot of important things he missed. And he says somethings differently than the way I remember.” So Matthew took Mark’s Gospel, plus his own memory (and perhaps notes), and built his own version that had the best of Mark in it and more (his version was preferred by the mostly-Jewish early Church, which is why it’s listed first among the Gospels).

Later, Luke, who had no connection at all to Christ, but who wanted to write a history of Christ in the style of Greek historians of his day (note the Greek of Luke is very much in line with this type of written history), referred to Mark, Matthew, and some eyewitness accounts. He picked what he thought was the best of Mark and Matthew but at times followed eyewitnesses who added more information or didn’t agree with Mark or Matthew.

Much later, near the end of his life, John, known to everyone in his time as “the beloved disciple,” decided that all three of the other Gospels were missing important things, most importantly, they all put Jesus ministry into just one year, but he remembers it was actually three. The three others talk mostly about events in Galilee, but other things happened in Judea. John focused on private conversations and events he believed were important that the other Gospels didn’t mention, letting them stand as the record of events they covered, only making corrections when he thougth it was necessary.

In this way of looking at things, there is no Q. The material ascribed to Q came from Matthew’s memory and Luke’s eyewitnesses. They don’t represent a single source. Show me how this hypothesis isn’t at least as valid as any hypothesis involving Q, if you can.

That’s nice and all, but I can’t help but detect a distinct flavor of wishful thinking in that recipe of yours. We may call the writer of Luke & Acts “Luke” out of convenience, but do we know he was a historical person as described by the stories? No, we have no evidence of that. And the Bible doesn’t count as evidence: in this context it’s a claim that needs evidence to verify it.

IIRC, Blog Dude posted a theory he was kicking around about Q being an early version of what turned into Luke. But he’s got enough articles on the Synoptic Problem that I can’t remember which one he put that in.

As for the link you shared, it’s interesting that for the Hebrew Syntax class I recently completed I wrote a paper that argued that the LXX version of Deuteronomy 32:8 is incorrect. I think the reference is to the “sons of Israel” not the “sons of God.” I can send you my paper if you’re interested. And, the rest of the argument is interesting, but I found it amusing that the New Testament prohibitions against worship of angels are used to “prove” his point that Michael was seen as the Christ…not in Christianity he wasn’t, nor in Judaism, either. Just in certain side cults that neither Judaism nor Christianity embraced.

Third answer, though it may list first–I’m not in the Texas National Guard. I live in Texas, but am an Army Reservist. The Guard and the Reserves are not the same thing. (Guards can be called up by state governors, the Reserves can only be called up by the Federal government).

Huh, today I learned a thing

Time for a stupid meme: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/16747829852689687/

Linkie that relates more to last weeks’ pr0n discussion: https://going-medieval.com/2018/04/18/on-sex-work-and-the-concept-of-rescue/