A Santa Claus Non-Believer Discovers Tolkien’s Father Christmas Letters

So I nearly forgot it’s the Christmas season and was getting ready to write an article totally unrelated to the holiday. Not that I haven’t decorated or bought presents, I have, but because for some reason I can’t fully explain, with the passage of time the calendar of holidays becomes increasingly less important to me in and of itself. Sure, I hope to see family members and enjoy gift-giving, but traditions have been fading in interest for me for a long time. Again, I’m not sure why, but it could be because I really do think of time in a linear way. I certainly experience linear time. Yes, there are some repetitions, but no Christmas really is the same for me as the previous year or other years before that–no year is the same as any other year–not just Christmas, but no day within any year is the same as any other day in any previous year for me. I’ve gone through some rather huge changes throughout the course of my life…which oddly brings me to my discovery of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Letters from Father Christmas.

For me, it’s a new discovery. I’m not really into Christmas literature, not much. Dicken’s A Christmas Carol is my favorite bit of literature specifically built on Christmas and for a number of years I also enjoyed the classic film It’s A Wonderful Life but frankly don’t bother to watch either any more. Same with the classic Grinch cartoon narrated by Boris Karloff. I know how they end.

That may make me sound like Ebenezer Scrooge to some readers or like the Grinch itself…but I don’t think that’s what it means. I am a generous person year-round and think about the incarnation of Christ year-round. Yes, everyone else talks about Christ’s birth much more on December 25th than other days and I’m fine with that. Yes, good, fine, enjoy! But I’m not deeply committed to the celebration of any particular date. Again, more and more, no date ever seems the same to me as it was in any previous year–each day seems unique to me, more and more.

No Santa For Baby Travis

Perhaps the seed of my disinterest in holidays starts with my parents never telling me Santa Claus was a real person. My mother thought (and still thinks) all forms of deliberate deceit are awful, so she told me from the beginning that Santa Claus wasn’t a real person. Which created a few rough arguments in elementary school in which I shattered the illusions of some other kids, not realizing that telling the truth on this topic, while not morally wrong, wasn’t really necessary. (Their illusions would get shattered no matter what I did or didn’t do, either softly or abruptly–it was only a matter of when and how.)

I grew up with a Christmas allowance, which I spent on presents for the family. While I enjoyed receiving presents as a child (one science fiction-related doll in particular–a Six Million Dollar Man doll, space capsule included!), some of my fondest Christmas memories of gifts are gifts I gave. And I remember shopping for gifts–looking for something I could give someone else and I feel that’s much richer tradition that believing gifts magically appear from Santa. That’s especially when we had hardly any money, so going out and buying something just because you wanted it at any other time of the year was out of the question. We would save money specifically for Christmas. Which is part of the reason Christmas isn’t as special anymore–I’m no longer so poor.

I did watch Santa-related television specials growing up, with the understanding they were deliberate fiction in the same way Star Trek the animated series I used to watch was. The Santa shows were OK, but The Little Drummer boy tore at my heart in a way no Santa show ever did–even though I realized there was no reason to believe there really was a little drummer boy. Santa, overall, just wasn’t that interesting to me.

Saint Nicholas For Travis’s Children

When I had the chance to teach my own children about Santa, I remembered my own experience of being at times what we can call a “Santa atheist” who smugly enjoyed telling other kids Santa wasn’t real. As a Santa non-believer, I was rather a total jerk at times, for again, reasons that didn’t really matter.

So I thought I’d teach my kids to be respectful of the tradition of Santa Claus without falsely telling them it was true. I told them about Saint Nicholas, who was a good man who lived a long time ago, who did many good things, including giving presents to children. Over a long time, the memory of Saint Nicholas changed to give him an imaginary home at the North Pole and many other imaginary features, but the real history was of an actual person, a good man who can be an example for how we can be good to others. So we should not be hostile to the idea of Santa Claus–the good thing is that Santa Claus is kind and generous, and we should be too.

How that translated when my kids talked to other kids who believed in Santa Claus was like this: “Oh, yeah, you believe in Santa Claus? Well, Santa Claus is dead!”

Then I’m talking to a parent of a kid who ran away bawling and she’s like, “What?” and I turn to my oldest son and say, “I never told you Santa was dead” and he’s like, “You said he lived a long time ago, that means he’s dead,” and I’m like unintended consequences of a narrative in which a reader goes beyond authorial intent…

(Pardon me, that true story makes me laugh…)

Father Christmas For Tolkien’s Children

So since I have limited interest in Christmas stories and Santa or the United Kingdom’s version of basically the same character known as “Father Christmas,” it’s perhaps not surprising that I didn’t even know about the J.R.R. Tolkien’s Father Christmas Letters until just recently. (Note E. Stephen Burnett wrote an article for Speculative Faith back in 2013 concerning Letters from Father Christmas in which the issue of whether Tolkien lied to his children or not and if that was OK or not was rather hotly debated. Which I don’t intend to repeat.)

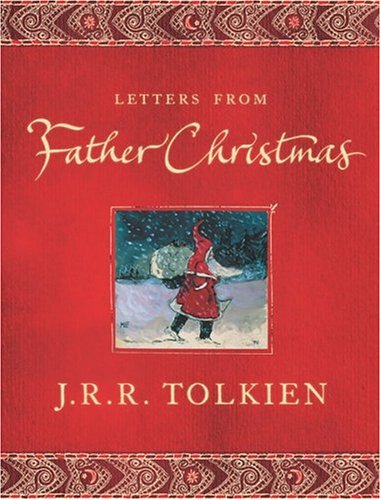

The harback edition cover of Letters From Father Christmas. Publisher: Mariner Books

My first response to discovering this book, which was based on letters Tolkien wrote to his children every Christmas starting in 1920 up through 1943 was “How charming! Fiction from Tolkien I’ve never heard of before, on the subject of Christmas!”

But hold the phone a second, that isn’t exactly what this book is. Yes, Tolkien’s children eventually realized the annual stories were fiction from their father, but at the time they thought these were actual letters, that Father Christmas really was writing them every year.

This book is not only a series of stories, the majority of which I haven’t even read, it reveals part of how the man generally credited with inventing the modern genre of fantasy celebrated the Christmas holiday with his family. In storytelling–but in stories he maintained were true for decades. Why did he do that?

I think the answer is simple enough–most people in 1920 thought telling children that Father Christmas (or Santa) is real was normal. Most people did that. Tolkien was simply following the common cultural practice of his day–just with much more creativity. Creating his own sub-tradition within the general holiday tradition.

Speaking of creativity, by the way, not only did Tolkien write letters, he drew pictures for his children and used a special type of shaky handwriting that was supposed to be based on Father Christmas’s age matching the calendar year (plus the cold up north!) I recommend checking out what he did via the Amazon “Look Inside” feature for the hardback edition of book I’m linking here. Charmingly creative.

Tolkien, A Man of His Times

To return to the reason Tolkien would maintain the fiction of Father Christmas with his children, that fact the vast majority of parents in the United Kingdom acted the same as him really is probably the best explanation. Tradition mattered to him from what I know of the man. But perhaps there’s another element in his reasoning.

Well before 1920, Darwinism was beginning to have a big impact in European intellectual circles. People were questioning if there was any truth to Christianity at all. Tolkien responded to the spirit of his time by holding onto Catholic tradition and even finding in old pre-Christian Pagan stories inspiration for new myths full of ideas (ideas, not allegories) related to things he believed to be true. Tolkien felt the Paganism of the past had inevitably led to Christianity and in fact to embrace Pagan epics would inevitably lead away from materialism and bring a person towards God.

C. S. Lewis thought similar things, though he was not quite as traditional as Tolkien and certainly more directly referenced Greek and Roman thought in Narnia and his Space Trilogy, as opposed to Germanic and Celtic myths, which Tolkien drew from more. For each man, fighting materialism and Modernism’s exaltation of mankind as a replacement for God were essential goals. And they found strength in traditions that embraced fiction that steered away from a mechanistic view of human beings, stories which pointed to the importance of the spiritual. As such Tolkien and Lewis to a degree were holdouts of the Romanic Era of literature from the 1800s.

So perhaps in teaching his children that Father Christmas had written to them, giving them that sense of delight in something inexplicable, he hoped to strengthen their resolve as Christians.

My View Doesn’t Match Tolkien’s

I feel though, looking back, that Tolkien and Lewis were missing something. Materialism and Modernism were not the end goals of powers opposed to God and all that’s godly. Modernism and the exaltation of mankind was just a step on the way to Postmodernism, which eagerly embraces stories while denying the existence of objective truth. Which loves stories with fantastical elements, but also deliberately in some cases infuses them with agendas which oppose belief in God.

Embracing imagination, any kind of imagination, is a step a way from the dry know-it-all materialism that defined Lewis’s character Eustace as he was introduced in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. In this, I would say Tolkien and Lewis were correct.

But human beings, the vast majority of us, have a fundamental desire for the transcendent. We are not as an overall whole going to embrace sterile materialism, even though it seemed like we would in 1920. I would say it will never happen that all of any society will become atheists. Instead, the danger is that we self-indulge in pleasures, including the pleasures of fiction, to the point we become numb to any truths they contain. That we will set up idols in stories and forget about the role of God, who Himself knows how to tell an inspiring story–but who also is True.

This ability to set up idols in fiction has always been part of the human race and yes did happen to dominate some societies much more than atheism ever has. It’s how the Pagan deities came to exist in the first place–ancient human imagination, running in the direction of idolatry. With the demonic world gleefully approving.

The literal return of Paganism I see as a threat, but in fact, the idolatry of most modern people isn’t so overt as a modern person literally worshipping a god like Thor. People worship their own self-fulfillment, their own physical pleasure, their own pride, in effect putting themselves in the position of being their own gods. Though also inspired and entertained by fictional heroes and superheroes.

We are not in the same era as Tolkien and Lewis. Perhaps it’s fitting that we don’t see tradition in the same way they did. Not all traditions are bulwarks for good, even if they can be sometimes.

Evaluating Tradition

For me, I don’t see tradition as a good reason to do anything. I don’t see tradition as a reliable bulwark against the spirit of our age–our age is more than willing to warp traditional stories.

Traditions should be evaluated for their content and embraced if good and discarded if not, I think. Likewise that’s how we should treat all stories.

But for me, that doesn’t mean cutting out the very existence of fiction to embrace a dry Christ-centric mirror of Materialism. No, stories are good or can be. But why not make fresh ones on fresh subjects? Why return to tradition simply because it is tradition?

So I wouldn’t have written the Letters From Father Christmas. I would have written Letters From Saint Nicholas, in which some time travel no doubt would be involved. Because, you know, Santa Claus is dead. 🙂

But I did find the Amazon preview of Tolkien’s letters charming. Especially the artwork and handwriting. I would have liked it better had Tolkien told his children from the beginning the letters were fiction, but who am I to judge Tolkien, “another man’s servant” (Romans 14:4)? (It’s enough that I do my best to follow what I think is right, guided by Scripture and the Holy Spirit. While of course doing my best to explain to others what I believe and why–but it is not my job to tell you specifically how you are to live your life concerning subjects not spelled out in detail in the Bible.)

Conclusion

So how many Speculative Faith readers have already read Tolkien’s Letters From Father Christmas? Am I the only one just discovering them? What did you think of them?

What do you think concerning the topic of generosity on Christmas? Is that an important tradition? Or is the birth of Christ enough?

And what do you think on the topic of following tradition or not following tradition in general? Do you create your own traditions or sub-traditions, like Tolkien did? Are you highly traditional yourself? Why so or why not? In what way or ways? Please leave a comment below.