Guest Blog: Mike Duran

Is âChristian Speculative Fictionâ an Oxymoron?

By Mike Duran

The label âChristian Speculative Fictionâ is an oxymoron. At least, thatâs one of my going theories.

The label âChristian Speculative Fictionâ is an oxymoron. At least, thatâs one of my going theories.

Believers who enjoy speculative fiction often bemoan the lack of such titles in Christian outlets. While Borders and Barnes and Noble contain aisles of horror, science fiction, graphic novels, and fantasy, spec titles comprise a relatively minuscule portion of the religious fiction market. Why is this?

I have several going theories. The one Iâd like to float to the Spec Faith crowd is this: To many believers, speculation, especially when it involves theology, is potentially un-Christian.

In 1988, Martin Scorseseâs film The Last Temptation of Christ opened to protests, boycotts and denunciations. Itâs based on Nikos Kazantzakisâ controversial book, the central thesis of which is that Jesus, while free from sin, was still subject to every form of temptation that humans face. Along the way, the author explores what it might have been like for Jesus to undergo the temptations of the flesh. Despite the fact that Scripture tells us Christ was âin all points tempted as we areâ (Heb. 4:15), the subject matter proved too offensive for many Christians. Note, this is not necessarily an endorsement of either the book or the film. Nevertheless, I think The Last Temptation of Christ controversy illustrates the inherent problems Christians face in approaching speculative titles.

At the heart of the Christian religion is a well-defined set of articles, a non-negotiable series of doctrines. To question these things is to undermine oneâs own faith (see: heretic). On the other hand, âquestioning thingsâ is at the heart of the speculative genre. Speculative fiction is best when it âspeculatesâ â when it tweaks reality, reinvents the rules, rewrites histories, and tinkers with the facts. In this way, speculative fiction, by its very nature, grates against the core of Christianity, which states that some things are beyond the pale of speculation.

Because of this, it is not uncommon to see Christian reviewers questioning the theology of a work of Christian fiction. Why? Because theology is at the heart of what defines Christian fiction.

I recently read the following on the website of an aspiring Christian novelist. The author described / defended their story thus:

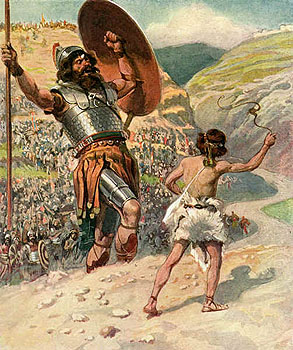

Although based on a true Biblical account, this is a fictional story. I have attempted to carefully craft the plot and shape my speculation without contradicting the Bible anywhere. If you find any such contradiction, or are offended in any way by the artistic liberties I have taken, I gladly defer to the account given in the book of Genesis [emphasis mine].

This author, perhaps unintentionally, reveals the rub. We must âshape [our] speculation without contradicting the Bible anywhere.â In other words, thereâs a line between âartistic libertyâ and âbiblical truth.â Problem is, does anyone know where that line is? Did Nikos Kazantzakis cross that line? Did Paul Young cross that line in The Shack? Did C.S. Lewis cross that line in The Great Divorce?

The tension between Christian theology and speculative fiction is always on the believerâs end. Atheists and postmodernists are not tethered to dogma in the way that we are. This is not to suggest that they are unrestricted by their own worldview, but that the boundaries of their worldview are a lot more expansive than ours. To the relativist, history is free to be re-written, and morality is up for grabs. Conversely, we walk a ânarrow road.â And, whether good or bad, it shows in our fiction.

Perhaps this is a good thing. Maybe we should be caretakers for the âancient boundaries.â Perhaps there are subjects and worlds and beliefs that should be off-limits to the Christian author. The question Iâm posing is whether or not this is why Christian speculative fiction lags. Is there an inherent incongruence between Christian theology and speculative fiction? Do we allow our theology to stifle our speculation or fuel it? Does our theology make the world a bigger place, or a smaller one? Does our theology create more possible worlds, or less?

Anyway, thatâs one of my going theories. Iâd love to hear some of your thoughts.

– – –

Mike Duran has lived in Southern California his entire life. He and his wife Lisa were married in 1980, and have raised four children, all of whom live in SoCal. He has chronicled his conversion to Christianity in a series of blog posts entitled “The Hard Road Home” at his blog, Decompose.

Mike Duran has lived in Southern California his entire life. He and his wife Lisa were married in 1980, and have raised four children, all of whom live in SoCal. He has chronicled his conversion to Christianity in a series of blog posts entitled “The Hard Road Home” at his blog, Decompose.

A former pastor, Mike now works in construction and is a freelance writer whose short stories, essays, and commentary have appeared in Relief Journal, Relevant Online, Novel Journey, Rue Morgue magazine, and other print and digital outlets.

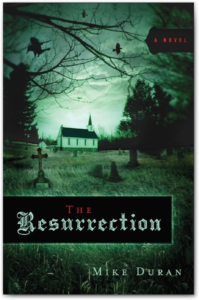

His debut novel, The Resurrection (Charisma House), releases this month.

Can we just nuke this? Can we finally and fully blast it to shreds? Or will there always be pieces of the monster that somehow repair themselves and lurch back to life, groaning, and head to the internet and post things like âC.S. Lewis was a heretic; hide your children!â?

Can we just nuke this? Can we finally and fully blast it to shreds? Or will there always be pieces of the monster that somehow repair themselves and lurch back to life, groaning, and head to the internet and post things like âC.S. Lewis was a heretic; hide your children!â?

But Lewis was not a universalist. He blatantly denied believing this throughout his works. Those who claim otherwise need to check to make sure theyâre absolutely right in their reading. If not, they are guilty of spreading slander about a Christian, and dishonoring the God of truth.

But Lewis was not a universalist. He blatantly denied believing this throughout his works. Those who claim otherwise need to check to make sure theyâre absolutely right in their reading. If not, they are guilty of spreading slander about a Christian, and dishonoring the God of truth.

Marc Schooley is a Texan, which may be empirically verified if you ever hear him speak. He is a Christian philosopher, theologian, Bible teacher, speaker, musician, and nascent Christian fiction writer who welcomes you to communicate with him at www.MarcSchooley.com, featuring quest appearances by MS Quixoteâwhich may or may not be his alter ego (a special commission has been established to investigate this matter). His novels The Dark Man and Königâs Fire blend action and paranormal twists with in-depth characters and Christian doctrines.

Marc Schooley is a Texan, which may be empirically verified if you ever hear him speak. He is a Christian philosopher, theologian, Bible teacher, speaker, musician, and nascent Christian fiction writer who welcomes you to communicate with him at www.MarcSchooley.com, featuring quest appearances by MS Quixoteâwhich may or may not be his alter ego (a special commission has been established to investigate this matter). His novels The Dark Man and Königâs Fire blend action and paranormal twists with in-depth characters and Christian doctrines.

Not long ago I made a New Yearâs Resolution that disgusted me. To myself Iâd said: âSelf, this year you hope to write a novel based in part on the theme of we all by nature crave to be the saviors of our own worlds. If you want to delve deeper into this mindset, you will likely need to read some books by those who, sad to say, provide bad examples of this exact view.â

Not long ago I made a New Yearâs Resolution that disgusted me. To myself Iâd said: âSelf, this year you hope to write a novel based in part on the theme of we all by nature crave to be the saviors of our own worlds. If you want to delve deeper into this mindset, you will likely need to read some books by those who, sad to say, provide bad examples of this exact view.â

Now, however, I donât need to read The Shack at all. Instead Iâve settled, by accident, for a little devotional that was last yearâs bestselling Christian book: Jesus Calling. Iâm sure its author meant the best in her âlisteningâ to Jesus every day, then writing whatever she felt He was saying to her. Where it gets confusing is how Christâs âspeakingâ to her somehow also applies to other readers who werenât, personally, listening themselves. Even more confusing: why try this at all? Does Scripture reveal this is some ability we can expect with the Presence of God?

Now, however, I donât need to read The Shack at all. Instead Iâve settled, by accident, for a little devotional that was last yearâs bestselling Christian book: Jesus Calling. Iâm sure its author meant the best in her âlisteningâ to Jesus every day, then writing whatever she felt He was saying to her. Where it gets confusing is how Christâs âspeakingâ to her somehow also applies to other readers who werenât, personally, listening themselves. Even more confusing: why try this at all? Does Scripture reveal this is some ability we can expect with the Presence of God?

This week the

This week the