Author Ted Kluck on spoofing Left Behind, evangelical kitsch, Christ-figures, growth as writers, Christian publishing and how most âyoung restless Reformedâ readers aren’t (yet?) into fiction.

Author Ted Kluck on spoofing Left Behind, evangelical kitsch, Christ-figures, growth as writers, Christian publishing and how most âyoung restless Reformedâ readers aren’t (yet?) into fiction.

E. Stephen Burnett: Today brings us Ted Kluck, author in multiple genres: sports and sports biography, doctrine and theology, cultural-Christianity parody, and now also end-times-thriller parody. With Kevin DeYoung, his pastor, he coauthored the two books that first brought him to my attention (more on that below): Why Weâre Not Emergent and Why We Love the Church.

I have to ask first about these: what led to these books, especially for a sportswriter who (Iâm guessing) could have thought, Can I write about this?

Ted Kluck: Back five or six years ago when the emergent church⢠was having its fifteen minutes of fame, I think people in our church assumed I was a lot cooler than I actually was/am, and started giving me Rob Bell, Don Miller and Brian McLaren books to read. Those books, in addition to being semi-interesting to read at times (Miller), were full of theological red-flags that were apparent even to me, a non-seminaried sports guy. So I approached Kevin, who is now a bona-fide A-List Reformed⢠Superstar, and we launched the alternating-chapters idea for Why Weâre Not Emergent. The rest, as they say, is about two-years worth of publishing history.

Ted Kluck: Back five or six years ago when the emergent church⢠was having its fifteen minutes of fame, I think people in our church assumed I was a lot cooler than I actually was/am, and started giving me Rob Bell, Don Miller and Brian McLaren books to read. Those books, in addition to being semi-interesting to read at times (Miller), were full of theological red-flags that were apparent even to me, a non-seminaried sports guy. So I approached Kevin, who is now a bona-fide A-List Reformed⢠Superstar, and we launched the alternating-chapters idea for Why Weâre Not Emergent. The rest, as they say, is about two-years worth of publishing history.

ESB: I mentioned it was Why Weâre Not Emergent that brought your and DeYoungâs names to my attention. Itâs a bit clichĂŠ by now â it was a âYoung, Restless, Reformedâ (YRR)-style Conference, in 2008, which also happened to offer all kinds of Deep-Doctrine Solid Books. So now youâre more well-known for those, yet youâve expanded your repertoire with your own publisher, Gut Check Press, and more, including a book on adoptive fatherhood, and The Reason for Sports: A Christian Fanifesto. Howâs that working out?

“What would Christianity look like if we were all college sophomores?”

Ted: Actually, we have that YRR-style conference to thank for whatever sales those books accomplished. Nothing sells books like Reformed bloggers. As to how itâs working out…(awkward chuckle)…itâs up and down. The books that didnât get (for whatever reason) the wholesale Reformed Seal of Approval definitely havenât sold as well. The take-home here is that I need to get either D.A. Carson or J.I. Packer to write the forewords for each of my books, regardless of subject matter. Gut Check Press has been the silver lining in a year or so of writing that has been kind of dark-cloudish. Gut Check has been nothing but pure fun and weâve made…wait for it…HUNDREDS of dollars.

ESB: Are the YRR sorts of Christians following your efforts into other genres? (Very possibly a leading question here. âŚ) If not, what books do the Gospel-driven, Puritan-quoting, affectionate-parody-worthy Christians like best to read?

Ted: Let me pause here to appreciate your questions. Okay. The short answer is no, they havenât followed my efforts into other genres. However, thatâs not to paint YRRers with a narrow brush in terms of their reading tendencies, which tend toward the following:

1.) Each other.

2.) John Piper.

3.) People who are old and dead.

4.) C.S. Lewis (but only in the sense that they love Lewis because he is old and dead and also because it gives them a chance to talk about the theological reservations they have vis-Ă -vis Lewis…we YRRers LOVE having theological reservations about things/people).

5.) John Piper.

ESB: Tell us about Beauty and the Mark of the Beast. Itâs âa dispensational thriller,â âwritten by committee,â first online, but later to be published by Gut Check Press. Sure, itâs a bit late after the fad, the site says in the FAQ â but itâs not the first time Christians were late to imitate something years after its peak. In fact, if thereâs anything evangelical Christians are original with, itâs end-times thrillers â even if they are âtacky, embarrassing, and mockable.â Want to expand your thoughts on the genre and its hangers-on?

Ted: Let me answer this question by telling a quick story. When I first visited the offices of the publisher responsible for Why Weâre Not Emergent, Why We Love the Church, The Reason for Sports, and Hello, I Love You, I was housed in a building called âJerry B. Jenkins Hallâ which was also home to a giant, muralish portrait of Jerry B. Jenkins who as youâll recall was one half of the juggernaut that produced all 186 volumes of the Left Behind series. It was at that moment that the seed was planted for this project, which Iâm sure will be every bit as successful, financially. Gut Check, as a company, realizes that thereâs a good buck in the end times racket.

Ted: Let me answer this question by telling a quick story. When I first visited the offices of the publisher responsible for Why Weâre Not Emergent, Why We Love the Church, The Reason for Sports, and Hello, I Love You, I was housed in a building called âJerry B. Jenkins Hallâ which was also home to a giant, muralish portrait of Jerry B. Jenkins who as youâll recall was one half of the juggernaut that produced all 186 volumes of the Left Behind series. It was at that moment that the seed was planted for this project, which Iâm sure will be every bit as successful, financially. Gut Check, as a company, realizes that thereâs a good buck in the end times racket.

ESB: Do you have or have you read the whole Left Behind series? (I do, and I may be the only YRR bloke who not only possesses all the books, mostly first-prints, but still feels some fondness for them).

Ted: I was introduced to these books in 1999 while I was living in Lithuania and waiting for the world to end in 2000, so they were timely both in the sense that they were in English, which was a huge plus in Lithuania, and they were about the end of the world. I think I read the first two or three of them and learned that if you have the right kind of tricked-out Jeep, you too can survive the rapture. It was a really formative time for me. And man, I hate to say it but I think you just lost your YRR card with that admission…expect some âconfrontations in loveâ real soon.

Ted: I was introduced to these books in 1999 while I was living in Lithuania and waiting for the world to end in 2000, so they were timely both in the sense that they were in English, which was a huge plus in Lithuania, and they were about the end of the world. I think I read the first two or three of them and learned that if you have the right kind of tricked-out Jeep, you too can survive the rapture. It was a really formative time for me. And man, I hate to say it but I think you just lost your YRR card with that admission…expect some âconfrontations in loveâ real soon.

ESB: (If Mark Driscoll can dress âgrungeâ and enjoy beer, I can enjoy my Left Behind memories because this is Missional.) If you follow modern evangelical Christian fiction offerings, whatâs your take on them? Iâm thinking here of two areas in particular: your views on how Christian novels are doing in showing Christâs truth and the Gospel in fiction, and how authors are doing in terms of creativity/originality/non-tackiness.

Ted: I actually have no idea here. I donât really follow modern evangelical Christian fiction. However (endorsement alert), Gut Check published a novel called 42 Months Dry: A Tale of Gods and Gunplay by a promising young novelist named Zachary Bartels, that will blow your mind all over your face. Itâs a modern day retelling of Elijah and the prophets of Baal, and reading it is like watching the best kind of action movie.

ESB: Whatâs your familiarity level with âspeculativeâ fiction â Christ-exalting fantasy, sci-fi, etc.?

Ted: I actually have more familiarity with crochet and cooking (thanks to my wife, Kristin) than I have with this genre.

ESB: What about other âYRRâ readers or writers you may know â do they enjoy Christian fiction, criticize whatâs there, and/or hope to do better? With all the Gospel-driven emphasis on taking back art, and writing more-Biblical and more-creative music (and not simply ripping off what the world does and instead making it all clean, saying âJesus,â etc.), Iâm curious whether YRR types are also considering fiction.

Ted: I donât think YRRers have âreclaimedâ (things we love: reclaiming things like art, fiction, the city, adoption, sex, etc.) fiction as of yet. And actually I donât see them/us doing so. Weâve (YRRers) have done a better job with rap music so far (see: Lecrae, Trip Lee, The Voice), than we have with fiction, which is either encouraging or discouraging depending on how you look at it.

ESB: Hereâs also one of the main reasons I had hoped to host you here: a single footnote in Why We Love the Church. Itâs on page 70: âIâm typing this at roughly the same time as the latest Batman movie, The Dark Knight, hits theaters. Just as in the Star Wars saga, expect Christian reviewers to find spiritual significance in the film so as to sort of allow themselves to like it with a clean conscience (see also: U2, and books like The Gospel According to Tony Soprano) when they should probably just go ahead and like it anyway.â

(I also saw The Dark Knightâs substitution/scapegoat motif, but didnât feel I needed to find it to enjoy the film.) And I think I know what you mean there; but of course Iâd rather hear more thoughts from you on that. (Of course, that may be a whole separate column someday â a prospect weâd not oppose).

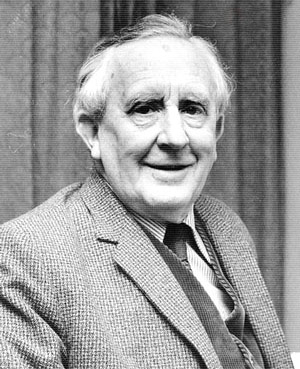

Ted: Yeah, I think I was just explaining that it would have been okay for Christians to like The Dark Knight even without finding the substitution motif or whatever. I really never âgotâ our (Christians) wholesale embracing of Lord of the Rings or The Matrix either. Personally, I find a lot of theological/socio-political imagery in Sly Stalloneâs seminal work, Rocky IV, in which he singlehandedly ends the Cold War. So much so (the imagery) that Zach Bartels and I co-wrote an academic white paper about it over at the Gut Check Press website. Spoiler alert: Apollo Creed = Christ Figure.

Ted: Yeah, I think I was just explaining that it would have been okay for Christians to like The Dark Knight even without finding the substitution motif or whatever. I really never âgotâ our (Christians) wholesale embracing of Lord of the Rings or The Matrix either. Personally, I find a lot of theological/socio-political imagery in Sly Stalloneâs seminal work, Rocky IV, in which he singlehandedly ends the Cold War. So much so (the imagery) that Zach Bartels and I co-wrote an academic white paper about it over at the Gut Check Press website. Spoiler alert: Apollo Creed = Christ Figure.

ESB: What might be some ways Christian fiction readers and writers, especially in âspeculativeâ genres, can seek Godâs truth and the Biblical Gospel, but also find ways to more creatively present these truths and glorify Him in stories, and not be all kitschy and embarrassing?

Ted: Honestly I think the best thing Christian writers can do for fiction (or nonfiction) is to grow in personal holiness and sanctification, pray for our writing to glorify God, be in Godâs word consistently, and just plain old get better at the craft. When weâre reading great novelists, weâll be much less likely to get all kitschy and embarrassing in our own work, unless, of course, weâre trying to be kitschy and embarrassing (see: Gut Checkâs end times thriller).

ESB: Bonus question: I must ask you about the male (and homeschooled) wrestler who turned down a chance to win a state championship, because it would have involved wrestling a girl.

Ted: I actually agree with the kid refusing to wrestle, but it bums me out that they (the state) put the kid in that position in the first place. I can sympathize with him not feeling entirely comfortable with that, for a variety of reasons. For what itâs worth, Iâm fine with girls wrestling, but they should have a different division, and have their own state tournament, etc.

ESB: Now Iâm out of questions, unless you want to make one up and answer it for yourself. Also, your next bookâs or booksâ release(s) dates and details?

Ted: Working on a book on discipleship and car restoration (seriously) that Iâm really pumped about. Writing it with a guy who kicked cocaine addiction and has been in and out of jail several times. Weâre fixing up an old Triumph Spitfire together…that one is called Dallas and the Spitfire and is being published by Bethany House Nonfiction sometime next year. Also doing a book with former Buffalo Bills quarterback Jim Kelly that Faith Words is publishing.

ESB: Thanks much for your time, Ted. Godspeed to you and yours!

Apparently I’ve been missing a stirring controversy within the Christian-fiction and Christian-visionary-fiction blogosphere. Perhaps you have as well, but if that’s the case, Sally Apokedak (who’s also written for this site) provides a summary for us all, in her recent post Bellyachers.

Apparently I’ve been missing a stirring controversy within the Christian-fiction and Christian-visionary-fiction blogosphere. Perhaps you have as well, but if that’s the case, Sally Apokedak (who’s also written for this site) provides a summary for us all, in her recent post Bellyachers.

Author Ted Kluck on spoofing Left Behind, evangelical kitsch, Christ-figures, growth as writers, Christian publishing and how most âyoung restless Reformedâ readers aren’t (yet?) into fiction.

Author Ted Kluck on spoofing Left Behind, evangelical kitsch, Christ-figures, growth as writers, Christian publishing and how most âyoung restless Reformedâ readers aren’t (yet?) into fiction. Ted Kluck: Back five or six years ago when the emergent church⢠was having its fifteen minutes of fame, I think people in our church assumed I was a lot cooler than I actually was/am, and started giving me Rob Bell, Don Miller and Brian McLaren books to read. Those books, in addition to being semi-interesting to read at times (Miller), were full of theological red-flags that were apparent even to me, a non-seminaried sports guy. So I approached Kevin, who is now a bona-fide A-List Reformed⢠Superstar, and we launched the alternating-chapters idea for Why Weâre Not Emergent. The rest, as they say, is about two-years worth of publishing history.

Ted Kluck: Back five or six years ago when the emergent church⢠was having its fifteen minutes of fame, I think people in our church assumed I was a lot cooler than I actually was/am, and started giving me Rob Bell, Don Miller and Brian McLaren books to read. Those books, in addition to being semi-interesting to read at times (Miller), were full of theological red-flags that were apparent even to me, a non-seminaried sports guy. So I approached Kevin, who is now a bona-fide A-List Reformed⢠Superstar, and we launched the alternating-chapters idea for Why Weâre Not Emergent. The rest, as they say, is about two-years worth of publishing history.

Ted: I was introduced to these books in 1999 while I was living in Lithuania and waiting for the world to end in 2000, so they were timely both in the sense that they were in English, which was a huge plus in Lithuania, and they were about the end of the world. I think I read the first two or three of them and learned that if you have the right kind of tricked-out Jeep, you too can survive the rapture. It was a really formative time for me. And man, I hate to say it but I think you just lost your YRR card with that admission…expect some âconfrontations in loveâ real soon.

Ted: I was introduced to these books in 1999 while I was living in Lithuania and waiting for the world to end in 2000, so they were timely both in the sense that they were in English, which was a huge plus in Lithuania, and they were about the end of the world. I think I read the first two or three of them and learned that if you have the right kind of tricked-out Jeep, you too can survive the rapture. It was a really formative time for me. And man, I hate to say it but I think you just lost your YRR card with that admission…expect some âconfrontations in loveâ real soon.

Ted: Yeah, I think I was just explaining that it would have been okay for Christians to like The Dark Knight even without finding the substitution motif or whatever. I really never âgotâ our (Christians) wholesale embracing of Lord of the Rings or The Matrix either. Personally, I find a lot of theological/socio-political imagery in Sly Stalloneâs seminal work, Rocky IV, in which he singlehandedly ends the Cold War. So much so (the imagery) that Zach Bartels and I co-wrote an academic white paper about it over at the Gut Check Press website. Spoiler alert: Apollo Creed = Christ Figure.

Ted: Yeah, I think I was just explaining that it would have been okay for Christians to like The Dark Knight even without finding the substitution motif or whatever. I really never âgotâ our (Christians) wholesale embracing of Lord of the Rings or The Matrix either. Personally, I find a lot of theological/socio-political imagery in Sly Stalloneâs seminal work, Rocky IV, in which he singlehandedly ends the Cold War. So much so (the imagery) that Zach Bartels and I co-wrote an academic white paper about it over at the Gut Check Press website. Spoiler alert: Apollo Creed = Christ Figure.

In reality, some of these other objectors have Bible-reading issues and their own love-in-Christ issues. As

In reality, some of these other objectors have Bible-reading issues and their own love-in-Christ issues. As

So since last

So since last

Thus, is it right or respectful, or even consistent, for Christian publishers to ban all use of Cusswords? Does that impose what could be a personal conviction on all its writers and readers, who may have different emphases: marketing to the Church, or to pagan âGreeksâ?

Thus, is it right or respectful, or even consistent, for Christian publishers to ban all use of Cusswords? Does that impose what could be a personal conviction on all its writers and readers, who may have different emphases: marketing to the Church, or to pagan âGreeksâ?

e. I regularly create productions that bring together performance and literary art, but I don’t have a painter’s bone in my body. Yet, I know that art has had a powerful effect on my imagination over the years.

e. I regularly create productions that bring together performance and literary art, but I don’t have a painter’s bone in my body. Yet, I know that art has had a powerful effect on my imagination over the years.