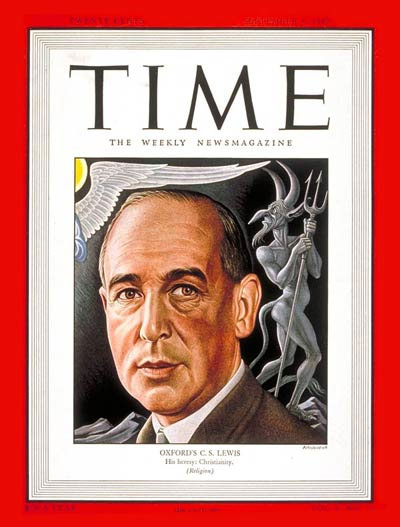

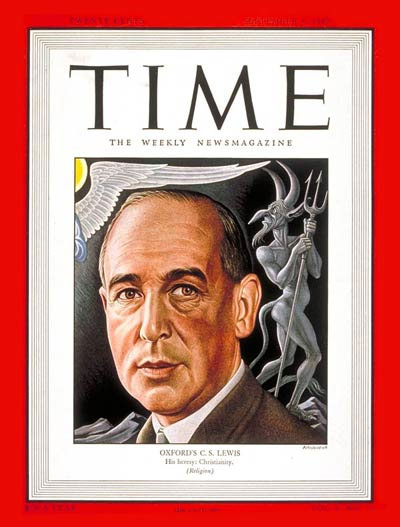

Last night I was shown another one â a website whose evangelical authors, surely with the best of intentions, ripped not only multiple C.S. Lewis quotes, but his whole life, out of context.

If I met the person who wrote this material, I would try to be gracious. After all, Christ saved me from so much worse; I was not, as the siteâs authors seem to have expected of Lewis, free from un-Godly thoughts and impulses before He saved me, and Iâm certainly still working on them! Still, Iâd challenge such Christians to survey the contents of this seriesâ parts one and two, attacking the notion that Lewis was a heretic and/or accepted universalism:

- Lewis clearly believed in Hell, and was not a universalist as some falsely accuse. Thus we must address his direct, written agreement that Hell is real, just and permanent.

- The character Emeth going to âheavenâ in The Chronicles of Narnia: The Last Battle is at best unclear, given that Narnia is a supposal, not allegory, and the variety of themes and interpretations that can be drawn from the vaguer-in-a-story Emeth Element.

Real Christians read Scripture (or should read it!) with right hermeneutics, not basing a whole System of ideas upon obscure verses, but instead seeking to let clearer passages interpret unclear ones, with heed to the original culture in which a book/text was written. Similarly, those who accuse Lewis of being a universalist need to survey his whole life and direction, and not let certain story tenets (which could âgoâ one way or the other!) not define his clearer statements.

Not universalist; still slightly fuzzy

That alone could refute C.S.-Lewis-was-a-universalist. Still letâs be fair: from what I have found, apparently Lewis did believe that God might provide some way to reach âgoodâ people who actually did desire to know the true God. This seems close to the modern term anonymous Christians â that is, that some people may be covered by Christâs grace without having directly embraced Him. Such was Kevin DeYoungâs reminder last month, after quoting Lewis:

There are people who do not accept the full Christian doctrine about Christ but who are so strongly attracted by Him that they are His in a much deeper sense than they themselves understand. There are people in other religions who are being led by Godâs secret influence to concentrate on those parts of their religion which are in agreement with Christianity, and who thus belong to Christ without knowing it. For example, a Buddhist of good will may be led to concentrate more and more on the Buddhist teaching about mercy and to leave in the background (though he might still say he believed) the Buddhist teaching on certain other points. [from Mere Christianity]

No matter how much we may like Lewis, this is simply a profound misunderstanding of the Spiritâs mission (and a rejection of John 14:6). The work of the Holy Spirit is to bring glory to Christ by taking what is hisâhis teaching, the truth about his death and resurrectionâand making it known. The Spirit does not work indiscriminately without the revelation of Christ in view.

Whether or not Lewis later revised his view, it is impossible to resolve it with Scripture. But is it heresy? After all, many Christians have similar-sounding beliefs about people born with mental issues, or children whoâve died in infancy. And as a scholar in such a secular realm, with even more anti-Biblical ideas about, should Lewis be faulted too much for buying into one early on?

In 2008 during a discussion on this, a friend of mine, Phillip Pugh, summarized Lewis like this:

One has to remember when reading Lewis that he is at heart a Medievalist even if his theology is basically Anglican. When reading Medieval works like Danteâs Divine Comedy (which had a profound effect on Lewis) we find that the âNoble pagansâ like Socrates, Plato, and Virgil, are placed in a sort of limbo where they are not suffering and yet there is no light. I think Lewis has something of this in mind, taking some cues from George MacDonald to embellish it (though not taking it to MacDonaldâs universalist extreme).

He is saying that Emeth had Tash and Aslan confused because of his cultural background. I disagree, but itâs not as bad as many would think.

I also disagree, but reiterate this: itâs not as bad as many would think. True Christians may believe wacky and/or un-Biblical things, such as: the King James Version (which one?) is Godâs inspired Word even more than the manuscripts from which it was translated; the sun orbits the Earth; Madalyn Murray OâHair and the FCC tried to ban Christian television in 1996 (sadly, they did not succeed); or Christians who read Harry Potter open themselves to demons.

More specifically about salvation, true Christians who understand that Jesus, Godâs Son, died for their sins, may also believe that if you donât speak in tongues, you donât have the Holy Spirit. They may, out of ignorance, disbelieve in the Trinity â a crucial doctrine for understanding how God works. They may be even fuzzy about the doctrine that Christ was born of a virgin.

But does that automatically rule out their salvation status?

Aiming for essential Christian beliefs

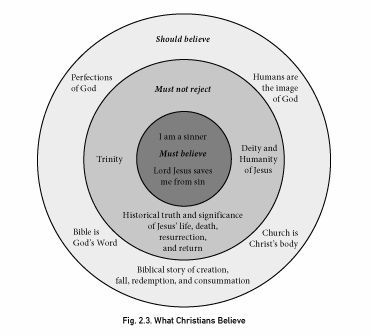

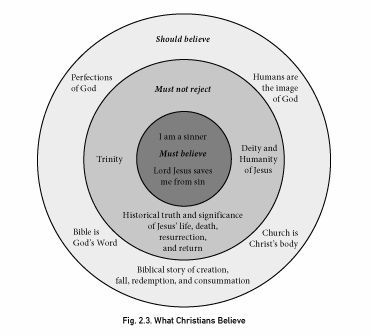

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? Thereâs an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study.

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? Thereâs an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study.

In the book of Acts, the bare minimum that a person must know and believe to be saved was that he was a sinner and that Jesus saved him from his sin. As Paul told the Philippian jailer, âBelieve in the Lord Jesus and you will be savedâ (Acts 16:29-31; cf. 10:43). This is enough to counter the postmodern innovator argument that we can be saved without knowing and believing in Jesus.

But any thinking convert will inquire further about this Jesus. While he may not know much more at the point of conversion than Jesus is the Lord who has saved him, he will quickly learn about Jesusâ life, death, resurrection, deity and humanity, and relation to the other two members of the Trinity. Anyone who rejects these core doctrines should fear for their soul.

According to the Athanasian Creed, whoever does not believe in the Trinity and the two natures of Jesus is damned. However, since it seems possible for a child to come to faith without knowing much about the Trinity or the hypostatic union (this is likely not the place where most parents begin), I take the Creedâs warning in a more benign wayâthat we do not need to know and believe in the Trinity and two natures of Christ to be saved, but that anyone who knowingly rejects them cannot be saved.

The final category is important doctrines which genuine Christians may unfortunately misconstrue. I think that every Christian should believe that Scripture is Godâs Word, know its story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation, and know something about the nature of God, what it means to be human, and what Jesus is doing through his church. However, many people have been genuine Christians without knowing or believing these things (though their ignorance or disbelief in these facts significantly diminished their Christian faith).

Thus, I believe that every doctrine in this diagram is crucially important for sound Christian faith. And some are so important that we cannot even be saved without them.

â from An Interview with Michael Wittmer, Between Two Worlds blog, Justin Taylor, Dec. 8, 2008 (boldface emphases added)

So â perhaps after checking that suggested diagram to ensure weâre in the faith! â I would put Lewis through these questions. For the center circle: Did he believe he was a sinner and that the Lord Jesus saved him from his sin? Most assuredly. From the outside circle: Did he accept the orthodox (though slightly less vital) beliefs about final redemption in a physical New Earth and the Churchâs nature? Not all of it. He also smoked tobacco all his life (!), as the Lewis-criticizing website I mentioned above gravely notes. But that doesnât make him a heretic.

The most interesting part comes in that center area of things Christians must not reject. Lewis was fuzzy about the Atonement, the nature of the Trinity, and â I would add this to it â the ultimate cause of Hell and sinnersâ eternal punishment, and what âtotal depravityâ means. He did not have access to the same resources that more-Biblical Christians may have today.

Therefore, I contend, Lewis was likely not directly exposed to those ideas and did not knowingly reject them for the reasons we hear from actual âhereticsâ today: humph, thatâs not âmyâ God.

The same is true of a Oneness Pentecostal acquaintance I have, who I think simply hasnât seen what the Trinity doctrine really states and defines. Itâs true of Christians who are hooked on conspiracy theories about Satanism and C.S. Lewis, and for whatever reason refuse to let the God of truth sanctify how they practice truth-telling in those areas. And letâs admit it: this is also true of so many of the early Church fathers, whose beliefs excelled amidst the doctrinal conflicts of their days, defending the faith in those areas, even if they faltered in other fields.

Conclusion: Lewis, though sometimes confused, a Christian

C.S. Lewis, though not a theologian and not a church father, is very similar to them: in the doctrinal areas under greatest assault in his society, he excelled. Rebutting unimaginative Christianity, he gave us The Chronicles of Narnia. Striking back against intellectual attacks on Christianity and anti-intellectual responses from other Christians, he gave us brilliant nonfiction.

He was not a universalist. He was not a closet compromising-with-Satan âpaganâ either (that could be another series). From what we can tell, he believed the essentials of the faith: that he was a sinner and that Christ, by grace, saved him. That, at the core, makes one a Christian.

What does that mean for those who insist he was a heretic and/or a universalist? It means that if theyâve read this far, God bless âem, theyâre now responsible for what theyâve read â just as Lewis would be, had he read and engaged a firm defense of Christâs absolutely-exclusive claims and rejected them. Here Iâve attempted to show specifically that Lewis did not accept the false notion of universalism. The other attacks I may handle another time, such as the âpaganâ thing.

But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again âLewis was a hereticâ or âLewis believed in universalism,â etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself â that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best itâs willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again âLewis was a hereticâ or âLewis believed in universalism,â etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself â that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best itâs willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

Yes, I know that it can be tempting to push back against Lewisâ popularity, especially because of many evangelicals who may actually over-value his works, quote them nonstop, or use his views in defense of anti-Biblical ideas and practices. And yes, as a general rule, if someone or something is popular with The World, thatâs a good signal for Christians to push back. But that alone is no reason to reject all of Lewisâ life and works. Christians should not live as if they must constantly Avoid Whatever is Popular in Culture, but instead live according to Christ. If culture happens to echo that, great; if culture doesnât, we oppose that. But our goal is to be for the Biblical Christ whoâs saved us, not merely Against All of The World. His popularity aside, Lewis was and remains a voice that glorifies God. Truth-minded Christians should thank Him for that.

Granted, he maintained that he did not write allegory, but his method of “supposal” (suppose God showed up in a world peopled by talking animals and dwarfs and other such mythical creatures, what form would He take?) lent itself to allegorical elements — though that’s not quite the same thing as an allegory like Animal Farm or The Stranger.

Granted, he maintained that he did not write allegory, but his method of “supposal” (suppose God showed up in a world peopled by talking animals and dwarfs and other such mythical creatures, what form would He take?) lent itself to allegorical elements — though that’s not quite the same thing as an allegory like Animal Farm or The Stranger.

This column may seem schizophrenic â likeunto a theme of one the most Google-able Christian novel titles of the past decade, Ted Dekkerâs Thr3e, in which an evil serial killer is shown able to threaten women, blow up a city bus, and abduct the main characterâs mother, but never, ever, not once, say any word worse then puke.

This column may seem schizophrenic â likeunto a theme of one the most Google-able Christian novel titles of the past decade, Ted Dekkerâs Thr3e, in which an evil serial killer is shown able to threaten women, blow up a city bus, and abduct the main characterâs mother, but never, ever, not once, say any word worse then puke.

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? Thereâs an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study.

Author and professor Mike Wittmer suggests no. Why? Thereâs an ignorance clause. Christians may not know some crucial Biblical truths, but they must not willfully reject them. His beliefs-target diagram has gotten about the internet: showing, in the center, truths that Christians must believe to be saved; in the middle, truths that Christians must not reject if they hear and understand them; and in the outside, truths that Christians should believe and study. But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again âLewis was a hereticâ or âLewis believed in universalism,â etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself â that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best itâs willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

But on this issue, if you go on from here and say again âLewis was a hereticâ or âLewis believed in universalism,â etc., after already having been corrected and told how to verify it yourself â that is not Biblical discernment or even understandable ignorance. Instead, at best itâs willful ignorance; at worst, God-dishonoring slander of a fellow believer.

So if youâre reading The Last Battle and it seems to be showing universalism â that Emeth got into the paradise of Aslanâs Country even though he was a pagan â bear in mind that Lewis more clearly wrote elsewhere that universalism was a lie. Thatâs clear enough from The Problem of Pain. And in his allegorical story The Great Divorce he repudiated the notion by name.

So if youâre reading The Last Battle and it seems to be showing universalism â that Emeth got into the paradise of Aslanâs Country even though he was a pagan â bear in mind that Lewis more clearly wrote elsewhere that universalism was a lie. Thatâs clear enough from The Problem of Pain. And in his allegorical story The Great Divorce he repudiated the notion by name. Now letâs get this specific story straight. Emeth, a pagan but noble Calormene who devoted his life to service of the evil entity Tash, somehow makes his way into Aslanâs Country. But heâs in a kind of in-between status. There Aslan meets him and Emeth immediately repents, sorry he has lived all his life for Tash. Aslan, though, reassures Emeth that Aslan has nevertheless counted his good deeds as service to Aslan instead of Tash. Then Aslan leaves Emeth to ponder that.

Now letâs get this specific story straight. Emeth, a pagan but noble Calormene who devoted his life to service of the evil entity Tash, somehow makes his way into Aslanâs Country. But heâs in a kind of in-between status. There Aslan meets him and Emeth immediately repents, sorry he has lived all his life for Tash. Aslan, though, reassures Emeth that Aslan has nevertheless counted his good deeds as service to Aslan instead of Tash. Then Aslan leaves Emeth to ponder that.