Deus Ex Machinas and The Doctor

The Doctor breaks rules. Thatâs been the case especially in the revived series (2005 â present) of the British television programme Doctor Who. And both head writers, Russell T. Davis (until late 2009) and Steven Moffatt, also seem to break plenty of ârules.â Web-search this: Doctor Who, deus ex machina, to see frequent complaints about supposed hat-trick story endings:

The Doctor breaks rules. Thatâs been the case especially in the revived series (2005 â present) of the British television programme Doctor Who. And both head writers, Russell T. Davis (until late 2009) and Steven Moffatt, also seem to break plenty of ârules.â Web-search this: Doctor Who, deus ex machina, to see frequent complaints about supposed hat-trick story endings:

Doctor Who, “The Parting Of The Ways.” Almost every season of Russell T. Davies’ Doctor Who series has ended with some kind of unlikely miracle fix, but the first one was by far the hardest to swallow. â i09.com, âThe 5 Types of Scifi Deus ex Machinasâ

Just be careful not to drop and break [your sonic screwdriver], Matt Smith, because, without it, you really only have deus ex machina on your side. â ROFLRazzi.com

âOn planet Earth itâs generally taken for granted that it’s a bad thing to introduce into a narrative some last-minute solution that was totally unexpected and unheralded ⊠The unexpected, unadvertised solution which kisses it all better is known as a deus ex machina â literally, a god from the machine. And a god from the machine is what the Doctor now is.â â Terry Pratchet, author of Discworld (Guardian.co.uk, May 4, 2010)

But Iâll argue here that a deus ex machina â a surprise twist at the last second to save oneâs characters or story â need not always be wrong, for at least four reasons.

Quick catchup: Doctor Who follows the adventures of a time-and-space-traveling Time Lord from an ancient race. Frequently he befriends someone from Earth, usually a young woman, and goes gallivanting about to save cities, people, worlds, and jolly often the entire universe.

As of today, his most recent adventure was Doctor Who: A Christmas Carol, which was not a direct ripoff of that story; instead, it only shared a starter premise, then gaily strode in other directions. The Doctorâs friends are stuck in a spaceship plummeting toward a planet, minutes away from being torn to shreds in its turbulent atmosphere. So the Doctor drops into the life of planet ruler Kazran Sardick (Michael Gambon â Dumbledore!), the only man who can adjust the planetâs atmosphere to allow the ship to land safely. Sardick, however, is the storyâs Scrooge equivalent, whose heart the Doctor must change to save the day.

That was a story summary you could get anywhere; now for the spoiler-laden paragraphs.

Inspired by Dickens, the Doctor uses his fantastic timeship, the TARDIS, to play a ghost of Christmas past. He actually drops into Sardickâs life as a child, rewriting time itself, and the adult Sardickâs memories even as the old man views videos of what happened. That seems to be working â until a complication that turns the teenaged Sardick against the Doctorâs visits.

After trying a present reminder of the shipâs victims, the Doctor finally tries his final effort.

The Doctor: Iâm not finished with you yet. You’ve seen the past, present. And now you need to see the future.

Sardick: Fine. Do it. Show me! Iâll die cold, alone and afraid. Of course I will. We all do. What difference does showing me make? Do you know why I’m going to let those people die? I donât get anything from it. Itâs just that I donât care. I’m not like you. I donât even want to be like you. I donât and never ever will care.

The Doctor: And I donât believe that.

Sardick: Then show me the future. Prove me wrong.

The Doctor: I am showing you the future. Iâm showing you right now.

(As the camera slowly moves the Doctor steps to the side, revealing Sardick himself as a child, standing beside the Doctor and gazing in shock at his older self. The older Sardick stares back, horrified.)

The Doctor: So what do you think? Is this who you want to become, Kazran?

Young Kazran Sardick: Dad?

End spoiler paragraphs and quotes. Is that a cheat ending, a wrongful deus ex machina? Not at all â and not just because I get choked up even now, picturing the scene in my mind. Itâs not a cheat because of DEM Reason 1: It fits perfectly with the storyâs established rules. For Doctor Who and this story in particular, itâs also a kind of twisted genius because itâs almost exactly what youâd expect a professional storyteller not to do: something so âexpectedâ as to simply have a character rewrite time itself. But if youâre the Doctor, you can do that.

End spoiler paragraphs and quotes. Is that a cheat ending, a wrongful deus ex machina? Not at all â and not just because I get choked up even now, picturing the scene in my mind. Itâs not a cheat because of DEM Reason 1: It fits perfectly with the storyâs established rules. For Doctor Who and this story in particular, itâs also a kind of twisted genius because itâs almost exactly what youâd expect a professional storyteller not to do: something so âexpectedâ as to simply have a character rewrite time itself. But if youâre the Doctor, you can do that.

"Temporal energy. Same screwdriver at different points in its own time stream."

Another quick spoiler: thus itâs also a perfectly acceptable, genius-almost-because-itâs-not method for the Doctor to escape an absolutely inescapable-from-the-inside prison box, as in last yearâs series 5 finale The Big Bang. He simply came back from the future to give a friend his sonic screwdriver, after which the friend headed to the box and unlocked it from the outside â revealing the past Doctor inside, still holding his screwdriver (touching the two screwdrivers generates an energy spark). All the Doctor needed to do was make sure to remember, in the future, to go back in time and give his friend the sonic screwdriver to free himself. Paradox!

DEM Reason 2: It works if a storyâs author is wise about setting a storyâs rules and their limits, and following them consistently. As a Time Lord, who can jump to almost any point in time and space, and even change some history, why couldnât the Doctor simply rewrite a manâs life? Or:

The Doctor: Oh, I wonât bother calling your servants. They quit. Apparently they won the lottery at exactly the same time. Which is a bit lucky when you think about it.

Sardick: There isnât a lottery!

The Doctor: As I say â lucky.

DEM Reason 3: We already expect a good story to end with our favorite characters winning. The only real surprise is how that conclusion comes about â the surprises and story twists that happen along the way. But no one watches a film or TV program (or programme), or reads a book, then sneers in annoyance at the end simply because things turned out all right.

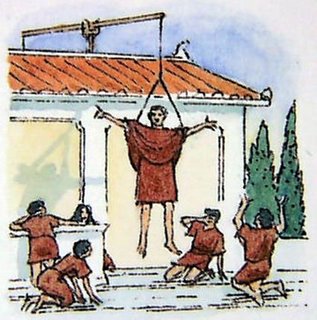

Yet DEM Reason 4 is similar to the reason old plays brought up a âgod out of the machine,â and even better because Christians know and believe a real God is already involved in our true worldâs story. God Himself has promised to carry out the ultimate âdeus ex machinaâ at the end of the universeâs present age. Those who know and love Him also already know the ending, and yet we still struggle with the difficulties of life, eh wot? No one who loves God accuses Him of cheating. (And we also donât stop arguing about exactly how that ending will play out; watch for this to pick up thanks not only to the 2012 myths, but Chinaâs rise to world power.)

Yet DEM Reason 4 is similar to the reason old plays brought up a âgod out of the machine,â and even better because Christians know and believe a real God is already involved in our true worldâs story. God Himself has promised to carry out the ultimate âdeus ex machinaâ at the end of the universeâs present age. Those who know and love Him also already know the ending, and yet we still struggle with the difficulties of life, eh wot? No one who loves God accuses Him of cheating. (And we also donât stop arguing about exactly how that ending will play out; watch for this to pick up thanks not only to the 2012 myths, but Chinaâs rise to world power.)

God has already established the real storyâs rules. But until that expected end â about which we donât know exactly what will happen anyway â He is playing out an even greater story. And that story is not because He expects us to pretend we donât know if the ending will be happy, but so He can show us even more what a wise and amazing Author He is.

By contrast, cursory searches for âsteampunkâ fiction donât turn up a lot, at least not yet: a fiction tribute or two to Jules Verne, a couple of early-hundreds Disney films that didnât do too well (Atlantis and Treasure Planet, the latter of which Iâve seen and still enjoy), some graphic novels, the 2009 film Sherlock Holmes, or the upcoming sequel series to Avatar: The Last Airbender, called The Legend of Korra. (Biased moment: hurrah for more animated Avatar! and may M. Night Shyamalan repent of

By contrast, cursory searches for âsteampunkâ fiction donât turn up a lot, at least not yet: a fiction tribute or two to Jules Verne, a couple of early-hundreds Disney films that didnât do too well (Atlantis and Treasure Planet, the latter of which Iâve seen and still enjoy), some graphic novels, the 2009 film Sherlock Holmes, or the upcoming sequel series to Avatar: The Last Airbender, called The Legend of Korra. (Biased moment: hurrah for more animated Avatar! and may M. Night Shyamalan repent of  Some stories also necessitate the quotes around the term steampunk, because technically theyâre not set in some alternate-history or even alternate-universe version of this world with steam-powered devices. Better terms, I suggest, might be retro-fantasy, or historical fantasy.

Some stories also necessitate the quotes around the term steampunk, because technically theyâre not set in some alternate-history or even alternate-universe version of this world with steam-powered devices. Better terms, I suggest, might be retro-fantasy, or historical fantasy.

And these secondary questions: Will Christian publishers embrace speculative fiction as the culture’s love affair with the genre continues? Will “science fiction” become the next dirty word to those seeking “safe fiction” rather than God-glorifying fiction? If not “horror,” what place does “supernatural suspense” have in Christian fiction? Can fantasy and science fiction share the spot light, or will the pendulum inevitably shift to one side or the other?

And these secondary questions: Will Christian publishers embrace speculative fiction as the culture’s love affair with the genre continues? Will “science fiction” become the next dirty word to those seeking “safe fiction” rather than God-glorifying fiction? If not “horror,” what place does “supernatural suspense” have in Christian fiction? Can fantasy and science fiction share the spot light, or will the pendulum inevitably shift to one side or the other?

Cathi-Lyn Dyck has been a published writer and poet since 2004, and a freelance editor since 2006. She can be found online at

Cathi-Lyn Dyck has been a published writer and poet since 2004, and a freelance editor since 2006. She can be found online at