You know those infamous âclip showsâ television sitcoms sometimes have, perhaps at the end of a season when the financial and ideas budgets are both running low? This will not be like that. Rather I present here a roundup of various blog clips plus commentary for your snacking and discussion enjoyment, as the newly regenerated Speculative Faith enters its second year.

Avoiding the âpriesthood of artistsâ

Musician Derek Webb professes Christianity and more-âlovingâ beliefs, but both of those seem missing in a recent interview, in which he implies that those who disagree with his approach:

From Spurgeon.org's 'Emergent Motivational Posters'

- are not loving, caring Christians concerned about their world;

- are hopelessly stuck in Christian-subculture ghettos;

- may not be as enlightened as the kinder, gentler, more-tolerant-than-those-other-bad-Christians-so-youâll-all-like-us-now,-yes? strain of faith that Webb professes.

Moreover, Webbâs words remind me of the trap that any Christian, regardless of denomination or political preferences, can fall into: striving to Fix The Churchâs/The Worldâs Problems more than Proclaim Godâs Gospel and His Glories. This also involves considering oneâs self part of an elitist priesthood of artists who can just, you know, think more and see things others cannot:

Part of the luxury of being an artist is that you not only can but kind of have a responsibility to think long and hard about things on behalf of those who might listen to your music. You can give them a jumping off point for subject matter that might be too tangled for most people in the busyness of their daily lives.

But musicians, novelists and any other artists, beware: we should not place ourselves above Godâs gift of pastors, teachers and believers in local churches that emphasize the Gospel and secondly its fruits in our lives, while we also fellowship even with those who donât âgetâ or enjoy our creative products or supposedly superior ideas. Otherwise, just as they might miss things we show in our artsy gifts, we might miss something others show in their Biblical teaching gifts.

P.S.: While I was writing this Wednesday, Frank Turk at Pyromaniacs was posting a firm yet gracious open letter to Webb, which also addresses potential artist arrogance, and other notes.

More on greater, God-centered stories

Last weekâs column may have left some wondering: how do we define âGod-centeredâ stories versus stories that are merely âGod-includingâ? I suggested that mainly entails recognizing that in the real-life story of our world, we must recognize that itâs we who fit into Godâs agenda, not vice-versa. But that brings up a few questions:

- What about stories in which God or Christ is not a âcharacterâ? Must we always include Him directly to keep them God-centered?

- Would it be inferior, then, to have a Christ-character-including story in which the Christ-figure barely appears? Must we spend most of the story following Him around or else risk making things too man-centered?

The best way of addressing this may be pointing to the âtrue mythsâ of Scripture itself. How should they be read? â especially when, sometimes, God does seem to manifest to help His people fulfill their Destinies, or He is hiding in the background.

Some great thoughts come from author/pastor Tim Keller, whom Novel Journey writer NoĂ«l De Vries quoted last week. I found the source of that quote and now offer more from Kellerâs original column. His emphasis is for preaching pastors, but his thoughts of how to tell true-life accounts from Scripture have nearly equal applications for other Christian storytellers:

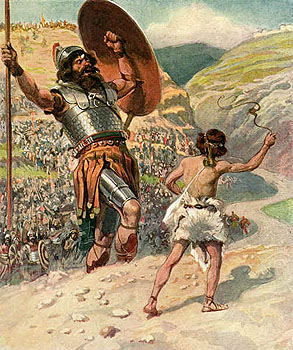

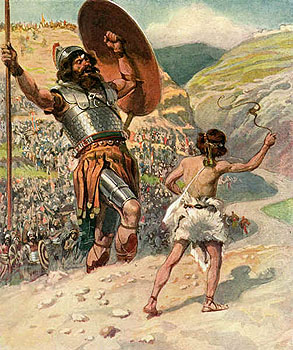

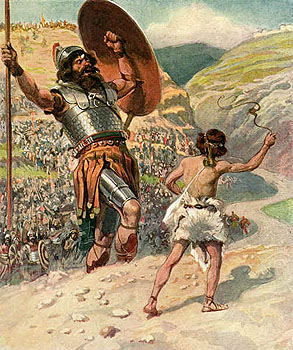

For example, look at the story of David and Goliath. What is the meaning of that narrative for us? Without reference to Christ, the story may be (usually is!) preached as: âThe bigger they come, the harder theyâll fall, if you just go into your battles with faith in the Lord. You may not be real big and powerful in yourself, but with God on your side, you can overcome giants.â But as soon as we ask: âhow is David foreshadowing the work of his greater Sonâ? We begin to see the same features of the story in a different light. The story is telling us that the Israelites can not go up against Goliath. They canât do it. They need a substitute. When David goes in on their behalf, he is not a full-grown man, but a vulnerable and weak figure, a mere boy. He goes virtually as a sacrificial lamb. But God uses his apparent weakness as the means to destroy the giant, and David becomes Israelâs champion-redeemer, so that his victory will be imputed to them. They get all the fruit of having fought the battle themselves.

This is a fundamentally different meaning than the one that arises from the non-Christocentric reading. There is, in the end, only two ways to read the Bible: is it basically about me or basically about Jesus? In other words, is it basically about what I must do, or basically about what he has done? If I read David and Goliath as basically giving me an example, then the story is really about me. I must summons up the faith and courage to fight the giants in my life. But if I read David and Goliath as basically showing me salvation through Jesus, then the story is really about him. Until I see that Jesus fought the real giants (sin, law, death) for me, I will never have the courage to be able to fight ordinary giants in life (suffering, disappointment, failure, criticism, hardship). For example how can I ever fight the âgiantâ of failure, unless I have a deep security that God will not abandon me? If I see David as my example, the story will never help me fight the failure/giant. But if I see David/Jesus as my substitute, whose victory is imputed to me, then I can stand before the failure/giant.

With that in mind: when you read Lord of the Rings, even without a direct Christ-figure a la Aslan, which elements stand out? Frodoâs bravery, Gondorâs majesty or Middle-earthâs beauty (themselves not sinful!) or the grander sweep of the epic that includes all these elements, yet points to Someone greater and more transcendent? Does Scripture affect us in similar ways â pointing to what God has done, over and above (though not ignoring) what His people will do in response? Do the other stories we enjoy, or read, have similar echoes of His greatest story?

On flawed characters in fiction

Last week Kaci Hill linked to the column about God-centered stories, and in reply Amy J. Rose Davis offered:

I find it interesting that Christians are very willing to talk about how Peter, Abram, Moses, Saul, David, Samson, et al were sinners and very messy heroes, but suggest that we shouldn’t have similar characters in our Christian fiction.

One reason for this disparity: many Christians are stuck in the rut of feeling they must have good-clean-relatively-flawless humans to Emulate. While admitting the Biblical heroes are not perfect, they may nevertheless fail to draw the conclusion and make the connection: we donât need to be those heroesâ public relations and clean up their images, and the reason God chose those people despite their wretchedness was to glorify Himself even more to His people!

So when we strive to make Christian stories more Christ-centered, that sets us free to tell great stories while using flawed characters â like God does with us. Their failings not only reflect our own, or give them empathetic appeal, but point to Jesus as the only flawless and glorious One.

Loving greater stories for Godâs sake

How do we avoid thinking too highly of ourselves as artists, seeking more God-centered stories, while keeping humansâ flaws in perspective? A possible twofold solution exists, and the first part is desiring to hunger for God-centeredness in all areas, while rejecting man-centered notions.

Amy Timcoâs Dec. 16 comment summarized a Christian writerâs unique motive for seeking this:

I need to stop writing, stop trying to inject more artificial majesty and power into my character, and examine my personal theology. We can only create what we know, and if the Christ-figure in my novel is pathetic, my conception of Christ is pathetic. Thereâs no way around it. And the only way to fix it is to fix my theology. Everything flows from that.

For weeks Iâve also meant to credit and thank Becky Miller for her further thoughts on glorifying Christ as more than a âsidekickâ in stories, instead making them increase our love for Him:

[S]tories that âtill the soilâ can be powerfully Christian. Such stories create the longing for the wholeness Christ gives, or for the acceptance His sacrifice made possible, or for the purpose His relationship frees us to achieve. I believe stories can show sacrificial love that is extraordinary and that will create a thirst for sacrificial love. I believe stories can show forgiveness that is pure and unmerited and it will create a thirst for similar mercy.

The second part of the solution: feeding that desire for Christ-centeredness, to know Him as He has revealed Himself, in ways that align as closely as possible with His Word.

Yet as the new year begins, it shouldnât be too clichĂ© to ask: is my desire growing? If not, what might I do to work out the salvation Christ has given me (Philippians 2: 12-13) and feed my hunger for His greatness, not just in the stories I enjoy or try to create, but in all that I do?

First: The Bible, of course. This year begins my wifeâs and my attempt to read more of it, not just during occasional studies but with the whole read-the-Bible-in-one-year plan.

As previously discussed, however, there can be wrong ways to read the Bible, and the read-it-to-find-mere-moral-lessons method is very infectious. Thatâs why reading nonfiction books that point to Scripture can also be helpful, whether they are topical works about specific doctrine or books that clarify how God (and human authors) intended Scriptureâs books to be read, mindful of context and original readers (How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth is a great introduction).

As previously discussed, however, there can be wrong ways to read the Bible, and the read-it-to-find-mere-moral-lessons method is very infectious. Thatâs why reading nonfiction books that point to Scripture can also be helpful, whether they are topical works about specific doctrine or books that clarify how God (and human authors) intended Scriptureâs books to be read, mindful of context and original readers (How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth is a great introduction).

Not only will reading and rightly applying Scripture help us focus better on Christ, it will subtly change the emphasis of our stories â those we enjoy and those we may write â toward Him. We wonât need to run around and artificial inject more Jesus parts; those will embed naturally.

And as Marc Schooley reminded us, imagine all the new ideas for fiction we find in nonfiction?

There are billions of characters to be written around Christian doctrines and they apply so vividly and directly to usâŠbecause they derive from the truths of Christianity. If the truths of Christianity are true, and they are, what study could bring you closer to a characterâs heart than Christian doctrine? What conflict, emotional involvement, or driving need could be closer to the human condition, and thus a readerâs heart, not too mention her own and most intimate thoughts and experiences?

[âŠ] By basing fiction upon deep doctrineâpick any one you wantâthe symbolism of any story will force its way into the text. You canât even prevent it from doing so actually.

Viva la resolution

Oh yes. That was a long one. Congratulations for making it to the end. And now that you are here, I wonder anew: what projects do you have coming in the new year? Resolutionsâą? Books to read? Books to write? Books that arenât actually books yet, until God blesses you with a publisher? Do share. Also know that all of us thank you so much for reading and contributing to Speculative Faith 2.0. And be sure to thank even more the master Author for this new year.

As previously discussed, however, there can be wrong ways to read the Bible, and the read-it-to-find-mere-moral-lessons method is very infectious. Thatâs why reading nonfiction books that point to Scripture can also be helpful, whether they are topical works about specific doctrine or books that clarify how God (and human authors) intended Scriptureâs books to be read, mindful of context and original readers (

As previously discussed, however, there can be wrong ways to read the Bible, and the read-it-to-find-mere-moral-lessons method is very infectious. Thatâs why reading nonfiction books that point to Scripture can also be helpful, whether they are topical works about specific doctrine or books that clarify how God (and human authors) intended Scriptureâs books to be read, mindful of context and original readers (

Number three – Imaginary Jesus by Matt Mikalatos (Tyndale). If you’d like to know more about this hilarious and spiritually thought-provoking book, you can read my review at

Number three – Imaginary Jesus by Matt Mikalatos (Tyndale). If you’d like to know more about this hilarious and spiritually thought-provoking book, you can read my review at  Number two – R. J. Anderson’s Wayfarer (HarperCollins). This YA fantasy published by by a general market publisher could easily move into the Number One slot, it’s that good. For details, see my

Number two – R. J. Anderson’s Wayfarer (HarperCollins). This YA fantasy published by by a general market publisher could easily move into the Number One slot, it’s that good. For details, see my  Number one – Jonathan Rogers’ The Charlatan’s Boy (WaterBrook). This is simply one of the best books, regardless of genre, you’re likely to read. To learn more, check out any of the CSFF Blog Tour reviews. A list is available

Number one – Jonathan Rogers’ The Charlatan’s Boy (WaterBrook). This is simply one of the best books, regardless of genre, you’re likely to read. To learn more, check out any of the CSFF Blog Tour reviews. A list is available

Politician, diplomat, Scotsman, Presbyterian, and writer of dozens of World War 1-era spy novels with occasional supernatural flair â that was John Buchan, who also, it seems, had a penchant for self-parody. That seems clear from this exchange early in his 1924 novel The Three Hostages, in which he satirizes thriller novelists who, he sarcastically suggests, are only employing cheap tricks.

Politician, diplomat, Scotsman, Presbyterian, and writer of dozens of World War 1-era spy novels with occasional supernatural flair â that was John Buchan, who also, it seems, had a penchant for self-parody. That seems clear from this exchange early in his 1924 novel The Three Hostages, in which he satirizes thriller novelists who, he sarcastically suggests, are only employing cheap tricks.