Fighting Man-Centered Monsters In Christian Fantasy

It was like New Yearâs Day came early, with reactions rolling one by one across time zones â only instead of being at midnight, the updates from friends came at about two hours past that, and instead of âHappy New Year,â they were expressions of horror, misery, woe and pain.

They were limited to those who had seen The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in theaters at the midnight showing.

âI officially do not want any more Narnia movies to be made,â lamented one friend, a longtime Narnia fan. âI am not even sure I’ll go see the next one.â I told him that if I were a drinking man, now might even be a good time for us to go out and get drunk.

The movie wasnât all bad. Reepicheep and Eustace were perfect, near-exact images of their equivalents in C.S. Lewisâs third Chronicle of Narnia. Aslan the great Lion was done very well.

But the filmâs addition of an Evil Green Mist⢠to fight not only itself fought against the bookâs themes of seeking honor, adventure and Aslanâs Country, it made little sense as a storyline. The threat was too vague and unsourced. How does it connect to the Dark Island? Why âfeedâ it captives and on what basis? How does it have teleporting powers? Where were the Mistâs captives â hypnotized? asleep? some kind of suspended animation? And just how, exactly, do the seven magic swords of Aslan provide power to defeat the Mist?

I wonât complain more about the Green Mistâ˘. For a far greater threat invaded the adaptation.

Trust me, I wanted to love Dawn Treader. Given time, I may be able at least to like it. Yet this element I will never appreciate, as I Tweeted shortly after coming back from the film:

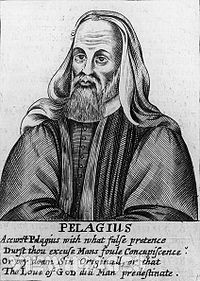

Whose horrible face was that I saw floating around in #DawnTreader ‘s Evil Green Mistâ˘? Why â could it be â Pelagius?

Pelagius was a heretic from the fourth and fifth centuries. But he was not the first to popularize his notions, and him dying didnât stop them from infecting popular Christianity (thanks also to the 19th-century revivalist Charles Finney). Wikipedia gives a great summary of Pelagianism:

[O]riginal sin did not taint Human nature and that mortal will is still capable of choosing good or evil without special Divine aid. Thus, Adamâs sin was âto set a bad exampleâ for his progeny, but his actions did not have the other consequences imputed to Original Sin. Pelagianism views the role of Jesus as âsetting a good exampleâ for the rest of humanity (thus counteracting Adamâs bad example) as well as providing an atonement for our sins.

The heretic Pelagius (ca. 354 – ca. 420/440)

Most Christians would rightly insist they donât believe all of that. Yet might some of it sound familiar? I know that Iâve previously accepted some of those beliefs. And how often have you heard something said like, âIf God commanded it, we must be able to do it ourselvesâ? Pelagianism.

That and similar beliefs are based on overreactions. Pelagius saw people who lived in a âcheap graceâ way and wanted to fix that problem. Unfortunately he didnât fix it according to Scripture.

Of course, Christians often accept un-Biblical notions, so it makes sense that non-Christians would even more buy into Pelagian ideas such as âlook into yourself to find goodness.â Sadly that proved itself again in Dawn Treader, despite the filmâs respect for Lewis in other ways.

As blogger Trevin Wax summarized:

How in the world does Lucyâs temptation for beauty become a message that tells viewers, âJust be yourself.â? Yes, the film gets it right that âevil is inside you.â Glad to see that. But the film teaches that the resolution to the evil in you comes from being true to your deeper, better self. Willpower saves.

Elsewhere, Reepicheep mentions â[earning] the rightâ to see Aslanâs Country. Aslan himself says âmy country was made for those with noble hearts.â

Perhaps I shouldnât have expected non-Christians to relay Dawn Treaderâs real worldview more effectively. Again, even Christians fall into emphasizing self-esteem more than God-esteem, as if we love God above ourselves but also expect Him to return that same favor in our direction.

But I can still complain, and suggest re-checking our beliefs, and not just as some legalistic or academic task. Pelagianismâs lies offend the God we love, split churches and hurt people.

More specifically, Pelagianism does weaken Christiansâ visionary fiction. I wonât say names here â partly because, sorry to say, the titles and authors can be forgettable! â but Iâve read a few fantasy books whose authors are trying to Imitate Lewis. But thereâs a catch: their Christ-figures, a la Aslan, arenât much like Aslan, much less so the Biblical Christ. Sure, they have all the loving-humble-helpful parts, but few to none of the sovereign-holy-kill-his-enemies parts. And these Christ-equivalents exist, not with their own missions, but mainly as sidekicks for the real hero of the story, the Self-Doubtful Often-Angsty Gifted protagonist, who is on a Quest.

Stories making God or a Christ-figure a means to fulfilling oneâs Destiny, rather than centering on Himself, are little better than atheism. Sadly, the âVoyage of the Dawn Treaderâ film suffered from those wrong beliefs. Without knowing and loving Godâs God-centeredness, so will other stories.

Much of C.S. Lewisâ genius, and Aslanâs grandeur, came from his knowing God is gracious *and* terrible. Miss that, and you de-claw the Lion.

Many other fantasies also want to imitate Lewis and convey truth about Christ. But they end up making Him a sidekick for humansâ adventures. Christ is not a sidekick. We are. He should be the center of all stories. Neglect that, and all Narnia-imitating hopefuls will ring hollow.

Sure, not every story can have an overt Jesus-figure or all the Gospel on all pages. Not even the Bible has that. Yet itâs about trajectory.

(That was from more Tweets.) Next week I may write more about fiction Pelagianism. Or about Santa Claus. It depends on reactions, which are certainly welcome.

Three ways to love a fiction âlegalistâ â that is, a Christian who opposes fantasy or fiction, or more often simply considers them pointless, useless and unnecessary to Godward growth:

Three ways to love a fiction âlegalistâ â that is, a Christian who opposes fantasy or fiction, or more often simply considers them pointless, useless and unnecessary to Godward growth: For a kid, you know, Iâd read the Bible stories over and over again. This was a fresh take on Who Christ was. Gandalfâs sacrifice, the returning King motif, that kind of thing. âŚ

For a kid, you know, Iâd read the Bible stories over and over again. This was a fresh take on Who Christ was. Gandalfâs sacrifice, the returning King motif, that kind of thing. âŚ Plus I had the images. I had images in my mind, rather than just the Bible story images â which were kind of lame, quite honestly, the kind that youâre fed, most of the time, in Sunday school. I had this powerful white-robed, bearded person, standing on a bridge and doing damage to a demon! ⌠And this enigmatic, charismatic king, whoâs coming back to his throne after years and years ⌠especially given the way people treated him, the utter reverence that was there. ⌠It opened up my mind to the reality, even though it was a fantasy.

Plus I had the images. I had images in my mind, rather than just the Bible story images â which were kind of lame, quite honestly, the kind that youâre fed, most of the time, in Sunday school. I had this powerful white-robed, bearded person, standing on a bridge and doing damage to a demon! ⌠And this enigmatic, charismatic king, whoâs coming back to his throne after years and years ⌠especially given the way people treated him, the utter reverence that was there. ⌠It opened up my mind to the reality, even though it was a fantasy.

This month the

This month the