Jordan Peeleâs Twilight Zone Newest Season Executes like Modern Day Parables

Over a month ago, I spoke about the uniqueness of Jordan Peeleâs Twilight Zone. In its sophomoric season, we find the episodes are geared more toward exploring universal pain. To illustrate, Iâll highlight three episodes, noting the âtip of the icebergâ storyline in all its speculative glory and then the deeper âbeneath the surfaceâ pain.

Season 2, Episode 1: Meet in the Middle (Is the voice in his head real?)

Tip of the iceberg: Our awkward store manager Phil played wonderfully by Jimmi Simpson, is understandably freaked out when he hears a womanâs voice in his head during a terrible date. As we travel with him on his journey through the extraordinary, Phil begins to spend more time with âAnnieâ. Over time, he accepts her intrusion into his mental space, sure that he isnât going crazy, but that âAnnieâ is a real person. He begins to go on âdatesâ with her. Several scenes show him sitting along at a restaurant laughing and smile with her, getting an ice cream cone with two spoons, or walking by himself, fully engrossed in his world and the relationship he has with her.

Until he uncovers a devastating lie. It changes the course of their relationship and onto a twisted conclusion.

Image copyright: CBS

Beneath the surface: This episode was a good strong start for the season. I found it a personification of the virtual world and how relationships are sometimes formed on a one-dimensional plane. Two users who meet and interact solely on a virtual plane (i. e., social media). In the show, Phil and Annie are only connected by the fact they can hear each otherâs voices in their heads. He canât see her, and she forbids him to look her up online. Over time, this relationship he has with Annie becomes more important than anything outside of it.

There’s a scene where he and she are talking. The background is particularly beautiful with snow and soft lights, but he’s not even paying attention to it…just talking to the voice in his head.

I sort of saw the twist coming a few times, but I liked the fact I was kept guessing. Was he crazy? Is this woman real? Is it a dis-associative personality?

Philâs character was illustrative of the growing isolation we’ve put ourselves in when we act and limit all interaction to just one plane â social media.

Season 2, Episode 1 Eight (Eight Brains vs Eight Brains)

Tip of the Iceberg: This episode is one of two creature stories. I looked forward to this because of my automatic love for monsters and was excited to see this explored. In this episodes, eight scientists from different countries are looking for a new species of octopus.

But why? Is it just for study or for a more nefarious reason? When they encounter this octopus, the tables are switched â whom exactly is stalking whom?

Beneath the surface: I liked this episode because it illustrates that although we humans are the head honchos on the planet, it doesnât mean weâre the only smart ones. Yes, I believe we have dominion over the Earth and are called by God to be good stewards. That doesnât mean we should try to dominate everything without regards to its life.

Researchers studying octopus on the Twilight Zone… Image copyright: CBS

The octopus is highly intelligent. In one scene, you see it watching the scientist with as a dispassionate glance as we would to it.

Evolutionary theory is often the crux for the reason of the shift of power. Although I donât believe in evolution, most secular sci-fi utilizes the theory to explain away stuff without having to think it through. Sort of like âGod of the Gapsâ theory. Instead, we have âEvolution of the Gapsâ theory.

Evolution did it! Thatâs all we need to know! Really? eyeroll

The more we learn about the animal kingdom, we find out that there are no such things as dumb animals. I saw this as a message of dominance vs stewardship and the dangerous pitfalls of thinking dominion equals subjugation.

Season 2, Episode 10 You May Also Like (After These Messages)

Tip of the Iceberg: A woman with everything finds out she really has nothing.

A commercial of a young girl traveling through the woods with a broken, naked doll fills the screen. A voiceover claims, âGet the EGG for your family and everything will be okay. Okay forever.

We follow a housewife who wakes up on a bed with no memory of how she got there. Talking to her neighbor she tells her that she loses time after she hears musical chords and then, sheâs back on the bed. This happens at regular intervals.

While this is happening, everyone is excited about getting their âEGGâ. No one, not even our housewife, knows what the EGG is but EVERYONE must have it. Thereâs speculation as to what it will do. Throughout this narrative, we learn that the housewife with everything doesnât have one thing. Itâs the catalyst of the show and to reveal it would be to reveal the big spoiler.

One of the characters in “You Might Also Like.” Image copyright: CBS

Beneath the surface: This show clearly indicates that people are never satisfied with what they have. They are always searching for something more. The EGG â due to great advertising, everyone is getting one. Theyâre voracious for it. When another housewife comes onto the scene with her EGG, our housewife asks to see it. Sheâs vehemently denied.

An aspect of this episode showed also how advertising reflects the human mind. Our housewives all wear similar clothes, have similar houses, even similar cars. Itâs Keeping Up with the Joneses to the umpteenth power.

Choosing a focus: character development or plot execution

Overall, this season had a disjointed feel to it. This does not mean I didnât enjoy it, but I felt that decisions were made behind the scenes that made for an average implementation as opposed to the sublime experience of the first season.

The second season, obviously, was given more money for production as we had more instances of CG. I don’t think the added CG served the season well. In the episodes I chose to highlight, the first one, âMeet in the Middleâ, had an even balance of both character development and plot execution. It should be noted that this episode, as far as I could tell, had no CG in it.

In âEightâ, I was glad to see indie horror filmmakers Justin Benson and Aaron Moorehead (âSpring,â âResolutionâ, and âThe Endlessâ) direct this episode. However, due to time constraints, the episode lacked their brilliant subtleties in the horror genre. In my opinion, they had to choose between character development or plot execution. They chose the latter, which led to our being disassociated with our cast. The cast only served as exposition so when the octopus chokes one guy, who cares?

My least favorite of the season was âYou May Also Likeâ. I’ll be frank. It irritated me. The story was extremely fractured. I’m all for red herrings but geez! It took me watching it twice to understand that the format was an intentional thing. Plus, the end of this one has a more nihilistic overtone which I did not enjoy. More on this in a minute.

Whereas the first season told a single story in bits, this second season was all over this place. Iâm in the process of re-watching it so I can plug in the parts with the holes that add to the overall story.

Nihilism versus solutions: the parables of Christ

I should begin with stating that I am enjoying this revitalization of the Twilight Zone. A critique simply points out the positives and the negatives. However, I noticed this season tangoed a lot with nihilistic thought.

The Twilight Zoneâs legacy focuses on extraordinary things happening to ordinary people. Not every episode in the original series had a bad ending. Some ended well. Others didnât. In every episode of season 2 of this revitalization, thereâs this lingering sense of nihilism.

As a refresher: nihilism: the rejection of all religious and moral principles, in the belief that life is meaningless.

With this as a foundation, the twists are often dark. Thereâs no glimmering light. It doesnât matter that horrible things happened â it happened, itâs predetermined, deal with it.

In old sci-fi stories, it used to be more about the adventure of discovery, pitting man against the unknown foe and succeeding. Modern sci-fi focuses on the unknown that essentially overwhelms us, and we cannot fight. We merely succumb to our human frailty. There is no one to save us. So, although the multi-layered storylines are woven into the narrative, there is no hope. All our efforts for success are meaningless.

Contrast this with the parables of Christ. Jesus Christ used storytelling to reveal spiritual things, to warn of oneâs choices and to present solutions, just to name a few.

In the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, the rich man had a choice to help Lazarus, but chose not to. He had multiple opportunities from what we can infer. Lazarus was the one left out in the cold. However, this parable shows us that when man ignores us, God watches and intervenes. When Lazarus died, he was taken to the bosom of Abraham. When the rich man died, he lifted his eyes in hell and torment. Could things have been different if he had answered the call of Lazarusâs needs?

In the parable of unmerciful servant, Christ uses this to illustrate the need for forgiveness. Again, the servant who owed ten thousand talents, who, after he had been shown mercy by the king, chose to not reciprocate. I mean, he choked the guy who owed him a hundred pence and threw him in jail. If this were the Twilight Zone, the episode would have ended here. But the King, when he heard about it, intervened in judgement. Again, showing the need for a savior. The solution is presented â forgiveness.

The Good Samaritan by Vincent Van Gogh

Probably one of the most famous, the parable of the good Samaritan, Christ illustrates who our true neighbors are. When the man is left for dead by robbers and ignored by the legalistic religious folks, the âsinnerâ is the one who cares for him. Again, in a nihilistic view, the man who had been left for dead would have died, his life having no meaning. In the person of the Samaritan, we see once more the need for a savior.

Why this fixation on Savior? Glad you asked! Christ did not let us continue to wallow in our sinful nature. As I mentioned last month, he didnât just narrate the events or point out the problem, He actively entered our sinful world and provided a solution through His blood. We donât have to stay trapped. We can escape if we so choose to accept His gift of salvation.

In closing, The Twilight Zone continues the tradition of presenting a multi-layered story but not a solution to the hard questions of life. Christ has, is, and always will give us a solution. It may not be the one we want, but itâs the one that leads us out of The Twilight Zone.

Milieu has to do with the story world—its physical, social, political, economic aspects.

Milieu has to do with the story world—its physical, social, political, economic aspects.

The last phrase is an allusion to Genesis, where God made the world and saw that it was good. It recalls, too, one of the loveliest images in Scripture, that of God creating the earth âwhile the morning stars sang together and all the angels shouted for joy.â This idea that the physical creation is a good thing, a thing to rejoice over, suffuses Chestertonâs works. He saw the goodness everywhere. Itâs a bad old world in many ways; popular catchphrases aside, there is nothing unprecedented about a pandemic. But Chesterton never got over the thought that itâs a good world, too, and it is pretty wonderful, after all, that the sky is blue and the grass is green.

The last phrase is an allusion to Genesis, where God made the world and saw that it was good. It recalls, too, one of the loveliest images in Scripture, that of God creating the earth âwhile the morning stars sang together and all the angels shouted for joy.â This idea that the physical creation is a good thing, a thing to rejoice over, suffuses Chestertonâs works. He saw the goodness everywhere. Itâs a bad old world in many ways; popular catchphrases aside, there is nothing unprecedented about a pandemic. But Chesterton never got over the thought that itâs a good world, too, and it is pretty wonderful, after all, that the sky is blue and the grass is green.

But now those two have been done, so how can a romance writer find a new something? One idea is to merge elements of “already been done” stories. Take Beauty and the Beast, for example, and merge that with Sleeping Beauty, and you have Shrek.

But now those two have been done, so how can a romance writer find a new something? One idea is to merge elements of “already been done” stories. Take Beauty and the Beast, for example, and merge that with Sleeping Beauty, and you have Shrek.

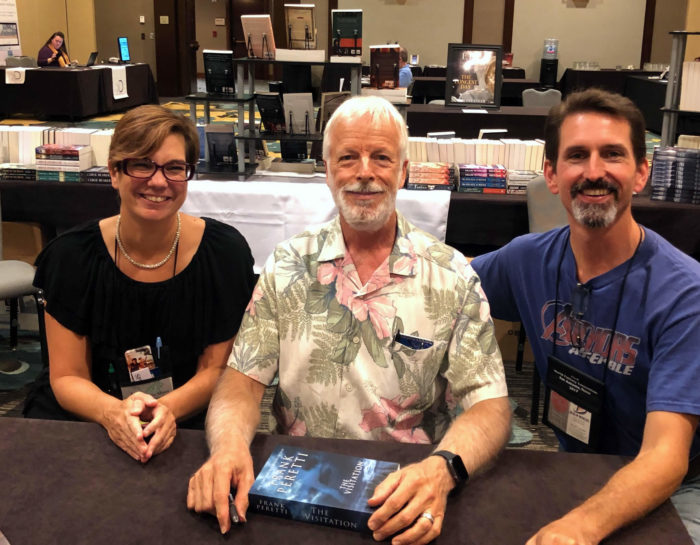

But who is Nathan Lumbatis? I mean, has he been writing long? Published other works? What’s he done in his life?

But who is Nathan Lumbatis? I mean, has he been writing long? Published other works? What’s he done in his life?