Some people are going to see the title of this post and wonder what this topic has to do with speculative fiction. Trust me, it does relate to a discussion of Lewis and Tolkein and other speculative fiction, which I will get to eventually, God enabling. But since this site is devoted to a Christian worldview in relation to speculative fiction, perhaps it’s best to start with our primary source of guidance (and inspiration) on all things related to the Christian faith–the Bible. What does the Bible actually say about race and racism?

Not all that much, actually. There is no specific mention of “race” as we know it in the Bible. There’s no specific command not to be a racist–though the Bible does say to “love your neighbor as yourself,” commands not to oppress foreigners (Exodus 22:21 and elsewhere), and says in Christ ethnic divisions are broken down (Colossians 3:11).

There’s no specific Bible command addressing smoking cigarettes, either. Though of course certain Bible principles address how to treat your own body and also the topic of coming under addiction, which cover smoking well enough. But smoking is not specifically addressed for historic reasons–because people in Bible times and places didn’t smoke. They had no access to tobacco or experience with other things a person might light on fire and deliberately smoke. (Well, they did have incense, but it’s not the same.)

I’m going to say that the reason racism isn’t called out by name in the Bible is the same reason smoking isn’t called out–because it used to be that racism as we know it didn’t exist. Showing how and when racism got to be a “thing” will be a topic for future posts.

Racism Isn’t the Same as Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentrism is the belief that a group or tribe or nation I belong to is better than those around me. It’s different from racism because it has no necessary connection to any physical trait of the various groups. Xhosa may in fact look somewhat different from Zulu on average–Chinese may look a bit different from Mongolians–French and German may differ a bit on average–Apache and Comanche don’t all have the exact same physical features–but all examples I just gave are peoples from the same race, according to racial theory. Who also have hated each other’s guts at times and have been at war with one another.

So what exactly is racism? I don’t want to fully explain yet, though I’ll get there. But to offer an overview: Racism first requires the idea that there are broad categories of human beings that apply to the whole world and certain traits mark those humans. And second, racism puts the “races” in an priority order of the most to least desirable. In the classic racism of the 19th Century, black Africans were put at the bottom of that order, with white Europeans at the top (and everyone else somewhere in between).

Ancient people did not think like that. They had two categories: 1. My group. 2. Not my group.

Is the Jew / Gentile Division Racist?

A modern person could import modern ideas about race into the Bible and see the strong cultural division between Jews and Gentiles as racist. But actually it isn’t. It’s ethnocentric at most, which isn’t the same.

I said “ethnocentric at most” because a believer in the Bible is forced to recognize that Judaism makes a different claim than most ethic groups. Um, yes, the Almighty really did talk to our ancestors, no kidding. We really are different from all other groups for that reason.

Note I’m not claiming all modern Jewish people think that way–in fact I would say most Jewish people don’t think that way. But some do. And certainly in ancient times Jewish people and the Israelites before them thought that way. And the Bible is written in such a way to support that–God did in fact choose a certain people. Even though the message He gave through them He also intended for the entire world. And it’s been Christianity’s major contribution to history to bring that message to the all the peoples of Planet Earth.

Saying the Bible teaching Judaism really is different from the rest of the beliefs of the world reminds me of Joseph innocently telling his brothers about the dream he had of them bowing down to him. Yes, he was simply telling the truth about something that happened to him. Nonetheless they reacted negatively to the idea. Likewise with people who see the Jew / Gentile division as racist.

Biblically, that division is legitimate, even though in Christ we are all equals. It definitely isn’t racism…and perhaps isn’t even entirely ethnocentric. It reflects real commands God really gave.

What Does the Bible Say About the Origin of Races?

It says all human beings are decended from the same mother and father. Actually in the Bible the male and female progenitors lived at different times. All humans have the same mother in Eve according to the Bible. But the most recent common male ancestor of us all would be Noah, who lived considerably after Eve.

The spread of nations across the planet is documented in Genesis 10. Well, actually the nations listed there go about as far west as possibly the western Mediterranean, about as far north as Central Asia, about as far south as Ethopia, and about as far east as India. Not the whole world by any means. But we can imagine the groups or tribes listed would produce yet other ethnicities over time, groups that would spread outward from the Middle East to eventually cover the whole world. Races developing via diffusion of an already rich inheritance of genes God put into people or by mutation and/or sexual selaection over all the planet are an natural extension of what the Bible already says.

Jesus loves the children of the world. Without irony, image copyright by Scientific American.

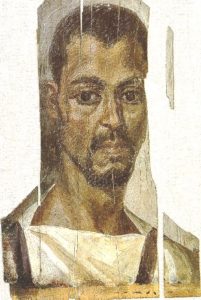

Note on occasion some Bible scholars have claimed Genesis 10 is only talking about people from West Asia, a.k.a. white people. This is plainly not true. This chapter multiple times mentions “Cush” which Biblical people knew as being from a land south of Egypt. That is, people from Cush, Cushites, were black Africans. Note the term does not just embrace the kingdom of Cush, which is roughly where Sudan is today. It goes all the way south and is sometimes is translated as “Ethiopian” in the Old Testament. Israelites certainly knew about Cushites having dark skin, please reference Jeremiah 13:23.

A Few Words on Cushites

Cushites or Ethiopians are mentioned a few times in the Bible. The Ethiopian Phillip evangelized in Acts chapter 8 obviously belonged to the modern racial category of “black.” Ebed-Melek, whose name literally means “servant (or slave) of the king” was said to be a Cushite and provided aid to the prophet Jeremiah in Jeremiah chapter 38. He probably was mentioned as a Cushite because he probably lived in Cush in his childhood. As opposed to it being a racial designation.

I Samuel 18 mentions the Israelites using a Cushite runner to deliver news of a battle. Note that by saying “Cushite” here, what it means is this person had immigrated from Cush–he was a known foreigner, and isn’t being designated as “Cushite” because of his race. Just like Uriah the Hittite came from a Hittite nation to Israel–Hittites being of the same races as Israelites according to racial theory. (Of course to the ancient Israelite, a Hittite was just as foreign as a Cushite.)

It could be that Cushites were exceptionally good athletes and were routinely used in Ancient Israel as message runners. But the Bible doesn’t actually say that. We have hardly any examples to work off of.

Moses was criticized by Aaron and Miriam for marrying a Cushite woman in Numbers 12 (what happened to Moses’s first wife, Zipporah, the Bible doesn’t say). Reading with modern eyes, that may seem racist of them. But the chapter shows them doing what appears to be a power grab that didn’t really relate all that much to Moses’s marriage. And besides, ethnocentrism accounts for the matter well enough. That is, we have every reason to believe Aaron and Miriam would object to the marriage because the woman was not an Israelite–not because she was black. (Note also though that God was on Moses’s side–not the side of Aaron and Miriam.)

A few times the Bible mentions Cushite warriors attacking Israel (after they’d conquered Egypt according to history, II Chron 12, 14). On several important occasions we know from history that Ancient Israel made an alliance with Egypt during a time when the dynasty of Egypt was a Cushite dynasty–a dynasty of Egypt after Egypt had been conquered by Cush. The Bible mentions the alliance with Egypt part a bit indirectly (2 Kings 18:21) but doesn’t mention that particular pharaoh was of Cushite descent. And why would the Bible mention it? As far as the Israelites were concerned, the fact the pharaoh identified with Egypt mattered more than his race.

What About the Curse on Ham?

People familiar with the history of racism in the United States will know in the antebellum South it was common to employ racism to justify slavery. Black people were supposedly destined to be slaves because of the three sons of Noah, one was regarded as being the ancestor of black Africans and was under a curse of God. Therefore this curse justified slavery.

But um…is there actually a Bible curse on Ham? Er, no.

The Bible records a curse on Canaan (Genesis 9:25), one of Ham’s sons. Not a curse on Ham.

The Canaanite creator deity, Megiddo, Stratum VII, Late Bronze II, 1400-1200 BC, showing what Canaanites looked like – Oriental Institute Museum.

And by the way, are all the descendants of Ham black? Er…no, the Bible portrays Ham as the ancestor of both white and black Africans –well, really more like light brown and dark brown–and also as the ancestor people not even in Africa, such as Nimrod.

Cush is the one unmistakable reference to black people in the Bible–and Cush is portrayed as one of Ham’s sons. A brother of Canaan–and the curse was on Canaan and not on Cush. There is zero Biblical support for a curse on Africans based on anything Noah or anyone else said. (What were the old-style Southern racists thinking? I will offer an explanation later–but really, their reasoning makes no sense.)

By the way, based on their artwork, if you saw a Canaanite walking around in modern times, you’d probably think he or she fell under the modern racial category of “white.” Albeit a relatively dark-skinned white person.

How Does the Bible Handle Racism?

One of the most powerful things Jesus taught is found in the Parable of the Good Samaritan. A story which illustrates that loving your neighbor crosses ethnic and religious barriers. Racial barriers as we know them today didn’t actually exist in Jesus time (as I will show in later posts). But the same principle applies–loving your neighbor should cross all pre-conceived lines. Racism should not exist for Christians. Yes, of course it does, but it shouldn’t.

A type of what we might consider ethnocentrism is supported in the Bible though. That is, we are to see the world in terms of believers and unbelievers, as is mentioned numerous times in the New Testament (e.g. I Cor 5:11-12). Yes, we are to love those outside the community of faith–but we are also to have and maintain a community of faith. But the community of faith should have no ethnic divisions within it (again, Col 3:11). Yes, ethnic groups will exist, but that is no reason to be separated from one another in Christ.

Conclusion

This is just the start of a series that I hope will be helpful in laying out a Christian way to look at issues of racism, systemic racism, racism in fiction, representation of races in fiction, and how we Christians should react to that. For those of us who see the Bible as our guideline for life, it’s important to note where it guides us. What it has to say.

So what are your thoughts on this post and this topic? Please make them known in the comments below.

changing a superior villain into a merely adequate hero. Not all creators know what to do with a smashing villain who entirely leaves off villainy. The story grows, too, harder to tell. There is high drama and even clarity in the conversion of villain to hero. Life, on the other side of redemption, sinks to something quieter and more muddled. It is easier to write a redemptive death than a redeemed life. And if the redeemed villain dies with all dispatch, his career as a hero will be too short to be disappointing.

changing a superior villain into a merely adequate hero. Not all creators know what to do with a smashing villain who entirely leaves off villainy. The story grows, too, harder to tell. There is high drama and even clarity in the conversion of villain to hero. Life, on the other side of redemption, sinks to something quieter and more muddled. It is easier to write a redemptive death than a redeemed life. And if the redeemed villain dies with all dispatch, his career as a hero will be too short to be disappointing.

It was at this time that I realized that I took nostalgic in the opposite sense that the critics meant it. I understood that I was meant to take it as a bad thing. I thought instead that it was, or in any case might be, a good thing. Iâve reflected since that there are other popular criticsâ phrases to which I gave a different connotation, and sometimes a different meaning, than they do.

It was at this time that I realized that I took nostalgic in the opposite sense that the critics meant it. I understood that I was meant to take it as a bad thing. I thought instead that it was, or in any case might be, a good thing. Iâve reflected since that there are other popular criticsâ phrases to which I gave a different connotation, and sometimes a different meaning, than they do.

I’ve been burned before—an author who deviates from the types of books I love, has disappointed. Not always. I can think of others who have veered from the type of book I originally loved, and I also loved the new venture.

I’ve been burned before—an author who deviates from the types of books I love, has disappointed. Not always. I can think of others who have veered from the type of book I originally loved, and I also loved the new venture.

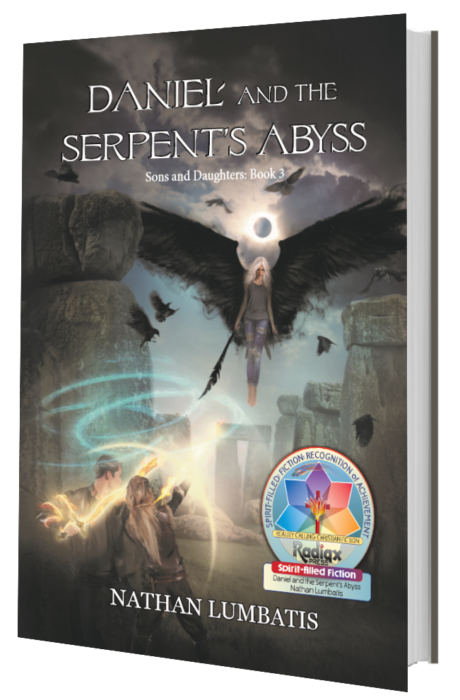

Daniel and the Sun Sword, Daniel and the Triune Quest, and Daniel and the Serpentâs Abyss are young adult, Christian fantasy novels exploring forgiveness, faith, spiritual warfare, and the reality of divine sonship. The recent release is the recipient of the Spirit-Filled Fiction Award.

Daniel and the Sun Sword, Daniel and the Triune Quest, and Daniel and the Serpentâs Abyss are young adult, Christian fantasy novels exploring forgiveness, faith, spiritual warfare, and the reality of divine sonship. The recent release is the recipient of the Spirit-Filled Fiction Award.

Nathan grew up in the woods of Alabama, where he spent his time exploring, hiking, and dreaming up stories. Now, as a child/adolescent therapist and author, heâs teaching kids and teens how to redeem their stories using Biblical principles. He still lives in Alabama, where you will find him with his wife and three kids every chance he gets.

Nathan grew up in the woods of Alabama, where he spent his time exploring, hiking, and dreaming up stories. Now, as a child/adolescent therapist and author, heâs teaching kids and teens how to redeem their stories using Biblical principles. He still lives in Alabama, where you will find him with his wife and three kids every chance he gets.