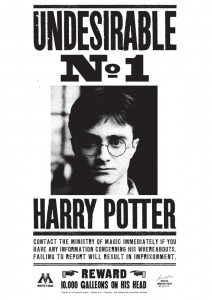

A worst-case scenario: along with the fun, whimsical things like flying brooms, potions, and washing dishes by wand-work, the Harry Potter stories do show what pagans today would call âwitchcraft.â And itâs not just the bad guys doing it. And itâs sinful practices that God does condemn in Scripture, either in the oft-cited Deuteronomy 18: 9-14 or elsewhere.

A worst-case scenario: along with the fun, whimsical things like flying brooms, potions, and washing dishes by wand-work, the Harry Potter stories do show what pagans today would call âwitchcraft.â And itâs not just the bad guys doing it. And itâs sinful practices that God does condemn in Scripture, either in the oft-cited Deuteronomy 18: 9-14 or elsewhere.

My contention: Even then, Christians strong in their faith could read the series, enjoying the true parts, and not sin. I believe we find this shown plainly in Scripture.

Sure, we would need to be more careful. We wouldnât abuse that freedom or strength to crow about how spiritually superior we are. Maybe we would not enjoy the material as much. And we would certainly not go on publicly theorizing how the author is actually a closet Christian who meant all along to proclaim Jesus (something we donât need to prove anyway in order to justify Harry Potter or any other secular story!). But we still neednât fear exposure to it.

In this seriesâ final column, I hope to show that how we discern Harry Potter affects how we do discernment in other ways, especially how we interact with other people âŚ

10. Because the Bible itself shows saints serving God and staying holy, even while knowing and studying actual pagan things.

For Christians who feel they must somehow show Harry Potter is just as âChristianâ a series as, say, The Chronicles of Narnia, but only its author hides it â I want to know: why do you feel we must prove that? And what happens when another popular and well-written series comes along that clearly isnât made by Christians but has truth anyway? Youâve just bought into this assumption: that âa story must be clearly Christian or else get shunned.â

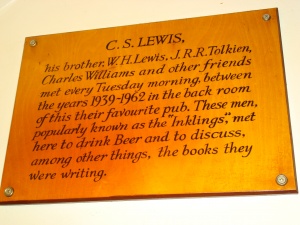

Scripture doesnât share this assumption. In Old Testament saints, Daniel in particular, and among New Testament believers, especially Paul, we see Godly practice of holiness, along with culture-engagement and without fear of Godâs-truth-opposing beliefs.

Yes, someone can abuse âengaging the cultureâ to excuse sinful motives and behavior. But still we find that Daniel, a strange man in a strange land, sought purity and holiness even while studying actual pagan witchcraft manuals in his secular advanced-education program. With Godâs help, he outclassed fellow scholars and grew in the pagan kingâs favor (Daniel 1). We see this also in the apostle Paul, the first specific missionary to the Gentiles. He not only didnât fear Greek literature or culture, but read and quoted a pagan poem that accidentally contained a truth about God, though it was wrongly applied to the false god Zeus (Acts 17).

Neither of these cases took place in a local church, say, like playing a secular song to appeal to nonbelievers. We donât read of Daniel trying to blend ecumenically some of the mystical beliefs with his prayer practices, or Paul endorsing all of the pagan poem while saying it was also from God. But neither of those men, in either Covenant, avoided even genuinely bad stuff. Instead they studied it â Daniel while staying personally holy and giving God the glory for it, and Paul to use as a conversation-starter outside a local church for non-Christians.

(For more, see the Imagination: for Godâs glory and othersâ good series, especially part 4.)

11. Because âsomeone else used it to sinâ is not a Biblical reason to avoid something, and no one can practice that consistently anyway.

âThere is not an ounce of doubt that the witchcraft societies, the sorcerer societies, have benefited from Harry Potter,â Wretched Radio host Todd Friel said on his June 10 program. âCall âem and ask âem.â That research is done and old, he added, and itâs incontrovertible.

Actually I havenât the slightest thought to controvert it â because Christians donât need to.

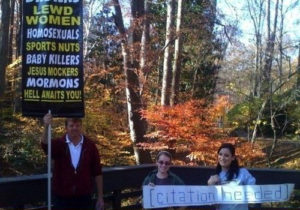

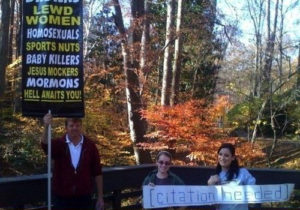

âPagans love the Harry Potter books.â That gets repeated often, and often without citation. But again, letâs assume that  is correct. What does it prove? Other pagans say they donât like being stereotyped as humans in robes who learn how to turn teacups into tabby cats or fly on brooms, all of which have nothing to do with actual pagan practices. (And if you will excuse a bit of snark, why are we listening to, and basing discernment on, what pagans say anyway?)

âPagans love the Harry Potter books.â That gets repeated often, and often without citation. But again, letâs assume that  is correct. What does it prove? Other pagans say they donât like being stereotyped as humans in robes who learn how to turn teacups into tabby cats or fly on brooms, all of which have nothing to do with actual pagan practices. (And if you will excuse a bit of snark, why are we listening to, and basing discernment on, what pagans say anyway?)

So at best, that charge results in a stalemate: your Anecdotes versus my Anecdote. This is not only transparently silly â is the next move to count up Anecdotes to see who has the most and declare a winner? â but isnât at all a Biblical method of deciding doctrine and practice.

What about the more-general argument that âsomeone else used it to sinâ?

Author Randy Alcorn has written and hosted several balanced articles about Harry Potter, among them thoughts from a former occultist named Sarah Anne Sumpolec (Jan. 21, 2010):

I think Harry Potter is probably good clean fantasy fun for 99 percent of its readers. Iâd be surprised if more than 1 percent went looking for the magical reality behind the fantasy. But then again, what is 1 percent of 500 million readers? How much of an impact is that?

That is indeed quite an impact, and I can understand Sumpolecâs concern â especially with her unique background. We should indeed be careful and seriously, yet winsomely, address the risks associated with any kind of art or fiction. Nothing is without potential of being abused for sin. But that is because humans are sinners. Weâll take anything and abuse it. Is that the Thingâs fault? No. If I wanted to get into real-life paganism, Iâd use any excuse.

Ultimately âsomeone else used it to sinâ is also an objection without Biblical basis. Moreover, if we tried to practice this same argument consistently, one could not read this column on the computer â someone else uses this same technology to gossip, look at porn, or waste time. One should avoid church â some elements of worship services may be borrowed from âpagans,â after all, and tainted! One might even want to reconsider the Bible itself â after all, many people have abused its truths to justify their own sin or even start cults. No one can practice this ethic consistently, and the Bible never levies this standard on us.

12. Because Christians should not base their discernment views only on the word of âweaker brothersâ and sisters.

The âwatch out for the weaker brotherâ argument is among the better objections to books like Harry Potter, or enjoying alcohol, big business earnings, or almost anything that could look âworldly.â For any Thing, be it book, song, or hobby, someone will be tempted to revert back to his tendency to abuse that thing for a sin â the real definition of âweaker brothers.â Thatâs a discussion Christians do need to have, along with rightful cautions against legalism.

"How to Tear Down The Strongholds of Rock Music." (Must be read in the voice of the old "Goofy" cartoon how-to narrator.)

However, the apostle Paul didnât permit legitimate âweaker brothersâ to set the agendas for everyone else. To the Corinthians he said that Christians who are stronger must be sensitive to conscience-tripping issues and abstain from even harmless activities if they hurt others. But that is far from looking to a new convert to set all doctrinal policy.

When I was younger I read a booklet we had lying about the house but never, to my memory, actually put into practice. (Its publisher was a ministry outfit called the Institute in Basic Life Principles, whose name sounds quite âOrwellian,â but unfairly so â it could be far worse.) Its title: âTen Scriptural Reasons Why The âRock Beatâ Is Evil in Any Form.â Its âevidenceâ: out-of-context Scripture and Anecdotes from people who it seems did abuse pop music and even âChristian contemporaryâ stuff for their own sin. And then there was this:

In April 1990, a Christian from Zimbabwe, Africa, arrived for his first visit to the United States. He is a native missionary under the Awana Youth Association. When he turned on a Christian radio station and listened to the music, he was shocked. Here is his report:

âI am very sensitive to the beat in music, because when I was a boy, I played the drums in our village worship rituals. The beat that I played on the drum was to get the demon spirits into the people. When I became a Christian, I rejected this kind of beat because I realized how damaging it was. When I turned on a Christian radio station in the United States, I was shocked. The same beat that I used to play to call up the evil spirits is in the music I heard on the Christian station.â (From this transcription.)

Now, how should a mature Christian, basing his discernment on the Bible, address this? One reply: âLighten up, dude, itâs just a drum, and the Devil doesnât work like that.â That takes his concern too casually. But the other extreme is followed here by this bookletâs writer: take it too seriously, as more true a Gospel result than what the Holy Spirit inspired the apostle Paul to say! Letâs all accept what our weaker brother, new in the faith, says about a Thing.

Neither response is Biblical. The former may occur more in a frivolity-obsessed evangelical culture. But the latter reaction may be worse because it actually accepts magical, mystical views as more true than Scripture itself, and in the name of âholiness.â

Isnât this also like saying âhe with the worst background gets to set the rules,â which treats a possible âweaker brotherâ as more discerning than faithful Christians who are more mature?

Paulâs advice to a new convert nervous about drum rhythms or fantasy books would surely be the same as his encouragement to the Corinthian church: for the sake of conscience, donât enjoy that Thing when this beloved âweaker brotherâ is around. But I also highly doubt Paul asked that his letters be off-limits to the weaker brothers. So they would also read there that nothing is intrinsically evil about meat previously sacrificed to idols. The temple ceremonies offering them to idols were evil, but not the meat itself. And they need to grow in this.

Stronger brothers should be sensitive and loving. Yet weaker brothers also need to grow up. How that best happens is a topic for other books or articles. But let us not act as if âweaker brothers,â instead of Christians stronger in faith, have the final word on discernment.

13. Because we may accidentally base our âdiscernmentâ mainly on personal dislike or lack of enjoyment of certain kinds of things.

Are we sure weâre not basing views on our own dislikes, or simple lack of enjoyment, for some stories, and expecting other Christians to think the same?

Elvis has left the Evil building (perhaps due to the Biblical principle of Sanctification If It's Over Forty Years Old).

The day after the Wretched Radio program in which Friel dismissed Harry Potter as being without a clearly Christian âside,â he played a clip from an old Elvis song and mentioned that The Princess Bride is one of his favorite movies. Yet last I checked, neither the song nor the comedy/fantasy film mentions or honors Christ or His Church. In fact, both of them imagine (yes, even the song) a âworldâ in which God does not exist or isnât a key Player!

So I must ask: how come the ârulesâ suddenly change when it comes to Harry Potter? How come some Christians say they expect only from that series a direct or allegorical inclusion of God or Christianity, or else reject it as evil and dangerous? Isnât that a double standard? (Well, we havenât seen hordes of people worshiping Elvis, or using him to sin or ⌠oh wait.)

Hereâs how the disparity just may arise: Elvis songs and The Princess Bride are older. Older stuff just happens to get away with more. Moreover, more people like old stuff â itâs their favorite Thing; itâs more acceptable among Christians to enjoy old stuff.

As for fantasy fiction â well, the quiet assumption exists that goes something like this: âwhy do you need that stuff at all? Better be safe than sorry. Scripture is sufficient anyway!â They naturally donât think to apply the same ethics to, say, worship songs, or draperies, or fine cooking, or any other movie or genre or creative Thing they enjoy but donât âneed.â

But this ignores two vital details: first, this stuff is old anyway, thanks to the Patron Saints, Lewis and Tolkien! Second, many Christians have testified how much fantasy and visionary tales have helped them grow in Christ. Sure, many professing Christians go too far and equate the nonsense in, say, The Shack with actual truth from the all-sufficient Word â but that doesnât make all fiction useless. Others can back up, with doctrine and practice, their claims that God has reminded them of Himself in secondary ways, like fantasy fiction.

All this applies to something like Twilight as well. Too bad. I dislike Twilight. By myself I canât personally imagine why Christians would want to waste time with that series. We can ask those kinds of questions, and challenge others who we may believe arenât making wise choices in their time or taking possible temptation sources seriously. But we should be consistent and not assume well, I know I wouldnât enjoy it, so why does he/she âneedâ it?

14. Because we may forget that true Christians may hold different views of discernment, but still avoid worldliness and grow in grace.

Thereâs a lot of good discernment-oriented material out there. And then thereâs the stuff that pits super-externally-âholyâ avoid-the-world-first types against, say, punk tattooed folks who claim theyâre Christians mainly because they agree with the statement âJesus loves you.â

Thereâs a lot of good discernment-oriented material out there. And then thereâs the stuff that pits super-externally-âholyâ avoid-the-world-first types against, say, punk tattooed folks who claim theyâre Christians mainly because they agree with the statement âJesus loves you.â

Itâs an unfair, false dichotomy, and truly discerning Christians should beware reinforcing it. Example: I should not portray all Twilight fans as crazed middle-aged moms, who wish they were younger, cheering when young men remove their shirts to show their sparkling pecs onscreen. (Ugh.) Yes, those do exist. But others can enjoy those books for other reasons. And if I see them growing in love for Christ, resulting in their taking on His attributes thanks to the Holy Spirit changing them from within, it does not honor Him to judge their motives.

The same is true with Harry Potter. Or other fantasy stories. Or video games. Or fatty foods. Or music. Or alcohol. Or organs versus âpraise teams.â ⌠Anything that can be discerned.

Who wouldâve thought a seven-book series about a boy wizard could help us learn so much?

As anyone who frequents Spec Faith on a regular basis knows, I’m a fantasy writer. However, I can’t help but notice that science fiction, along with an amalgamation best termed science fantasy, is slowly on the rise.

As anyone who frequents Spec Faith on a regular basis knows, I’m a fantasy writer. However, I can’t help but notice that science fiction, along with an amalgamation best termed science fantasy, is slowly on the rise.