Steve Rzasa was born and raised in South Jersey, and fell in love with books â especially science fiction novels and historical volumes â at an early age. He and his wife Carrie have two boys and live in Buffalo, Wyoming. A former community newspaper reporter and editor, and current librarian, Steveâs first novels in The Face of the Deep series, The Word Reclaimed and The Word Unleashed, were published by Marcher Lord Press. A third novel set in the same story-world â Broken Sight: A Rescue Ops Mission â will release later this year. This week Speculative Faith editor E. Stephen Burnett caught up with Steve to ask about his career, writing and world-craft.

Steve Rzasa was born and raised in South Jersey, and fell in love with books â especially science fiction novels and historical volumes â at an early age. He and his wife Carrie have two boys and live in Buffalo, Wyoming. A former community newspaper reporter and editor, and current librarian, Steveâs first novels in The Face of the Deep series, The Word Reclaimed and The Word Unleashed, were published by Marcher Lord Press. A third novel set in the same story-world â Broken Sight: A Rescue Ops Mission â will release later this year. This week Speculative Faith editor E. Stephen Burnett caught up with Steve to ask about his career, writing and world-craft.

ESB: First, everyone else likely knows how to say your last name; so far, I donât!

Steve Rzasa: Itâs pronounced âRa-zah.â And donât worry, youâre not the first person to ask that question. As far as I have researched, itâs of Polish origin â specifically from the southeastern corner of Poland thatâs belonged to countless kingdoms and empires over the past century. My great-grandfather Frank (Franzicek in his native tongue) emigrated to Pennsylvania in the early 1900s.

ESB: Thanks for that. Now, letâs put this above the fold: your new novel, set in the same world of The Word Reclaimed and The Word Unleashed (with Marcher Lord Press), releases soon. Want to discuss some about the new book?

Steve: Sure. This pending third novel is tentatively titled Broken Sight: A Rescue Ops Mission. If you stop by my website, www.steverzasa.com, youâll find a short story I penned back in 2009 called Rescued. This tale, which came in second place for the Anthanatos Christian Writing contest, introduces Lt. Brian Gaudette of the Rescue Corps â a group analogous to todayâs Coast Guard. Broken Sight follows Brianâs new command and crew about two years after the conclusion of The Word Unleashed, as the newly renamed Rescue Operations expands into its law enforcement role. Brian, meanwhile, is dealing with a likely divorce, an insubordinate ex-pirate for a first officer, and something else heâs never faced â religious freedom.

So, this novel chronologically follows my previous two, but is a new adventure in its own right. Expect some of my favorite secondary characters to make important appearances, however.

ESB: Unlike many Christian spec-fic authors, it seems, you have a background in community journalism. (Same here, by the way.) How did that come about? Also, how might your writing nonfiction in small-town settings â city council meetings, small businesses, and ribbon-cuttings, am I right? â have informed your writing fiction in large-universe settings?

Steve: You are correct, Stephen. I worked for eight years in newspapers, as a reporter, assistant editor and finally as an editor for one year. Reporting gave me the training to talk with others, a real task for me since I was naturally shy to start. It also taught me that people donât speak in polished paragraphs â they stutter, âuhâ and âumâ a lot, and generally donât make sense about a quarter of the time. I think that helped tremendously as I worked on character dialogue. And covering all those aforementioned aspects of small-town life helped me see just how complex even the day-to-day of a small community could be. Translating that feel to a galaxy was quite a challenge, and I drew on those experiences to fill in the gaps, so to speak.

ESB: Many Christians who get into trying to write visionary stories seem to veer toward fantasy, taking after the Patron Saints, Lewis and Tolkien, who started the modern Christian fantasy (and fantasy altogether!) genres. Science fiction, though, seems to have a different worldview ancestor â secular humanism (despite some politically conservative overtones; as discussed here). What have you enjoyed about science fiction as a genre, and how do you believe Christian readers and writers can âredeemâ sci-fi elements for Godâs glory and Kingdom?

Steve: Letâs get the confession out in the open â I am a devoted adherent to space opera. Thatâs the sect of sci-fi thatâs always drawn me. Thereâs just something fantastic about these gleaming starships that whisk you to any corner of the universe, whether itâs off to an exotic world on a mission of exploration, or into the heart of enemy space to defeat the evil empire. I think I also admired the optimism of sci-fi that said yes, we can survive beyond this troubled and rapidly changing century-and-a-half on Earth.

Steve: Letâs get the confession out in the open â I am a devoted adherent to space opera. Thatâs the sect of sci-fi thatâs always drawn me. Thereâs just something fantastic about these gleaming starships that whisk you to any corner of the universe, whether itâs off to an exotic world on a mission of exploration, or into the heart of enemy space to defeat the evil empire. I think I also admired the optimism of sci-fi that said yes, we can survive beyond this troubled and rapidly changing century-and-a-half on Earth.

Now, of course, that tenet of sci-fi is based on manâs effort â which we know is fallible. What I see now is Christian sci-fi writers who are redeeming this genre by injecting their own view that it is God who rules over this universe and loves his human children â even when we fail and come crying to his Son. And I also like reading sci-fi in which the main characters are Christians! Years of wonderful stories marred by people who harbor a disdain or even hatred for God puts a serious crimp in your desire to try new sci-fi books. But I think that the newest crop of authors â especially my cohorts Kerry Nietz and Kirk Outerbridge at Marcher Lord Press â are taking the genre in exciting new directions.

ESB: A big topic here this week is what Christian authors should read (Iâd apply this also to readers who love spec-fic). That has included reading contemporary stories, secular fiction, and last year your fellow Marcher Lord, Marc Schooley, had said fiction writers must read doctrine and nonfiction. What do you think? What have you read, and what sorts of books have you considered getting into?

Steve: I agree wholeheartedly with Marc â I would only generalize by saying writers should read every kind of book, fiction or otherwise. Within the last year, Iâve read Holmes on the Range by Steve Hockensmith (detective work by two cowboy brothers in 1892 Montana), Priceless by Robert Wittman (an ex-FBI agentâs bio on art crime), Understanding Four Views of the Lordâs Supper (self-explanatory, I hope), and the graphic novel Serenity: Those Left Behind (Browncoats unite!). There are many tips and tools we as writers can pick up from each other, even in reading nonfiction work. And history informs my own plots and ideas greatly. One of the easiest ways to come up with a story idea is to take historical events and change key facts and locations.

As for doctrine, well, I come from a varied theological background â raised Roman Catholic, grumpily agnostic in college before a conversion moment that led into an Assemblies of God Church, then seven years with fundamentalist (their own description, not a pejorative) Baptists before joining a Lutheran Church (Missouri Synod). The Catholicism aside â letâs call that cultural Christianity since it was the church my parents attended â Iâve tended not to dwell much on the minutia of doctrine, save for the basics of the Trinity and salvation by grace. I think that varied experience with different Christians instilled in me a desire to learn all I could about different denominations â and thatâs why I try to emphasis the brotherhood of Christianity in my writing.

ESB: Want to overview your journey to publication? How did you market your novels, what challenges did you face, and how did you become a Marcher Lord?

Steve: I came up for the idea for The Face of the Deep (the series name for the two novels) back around 2003. It took about five years of writing to get about a third of the way done on this one book, which at the time was called Commissioned. Being a reporter, writing was often the last thing I felt like doing when I got home from work â I didnât even want to look at a keyboard. But a, shall we say, forced change in employment got me into another career path â libraries â that not only exposed me to more books but also gave back the desire to write when not at work. Suffice it to say that nine months after I lost my job and started working at our local county library, I finished Commissioned.

Steve: I came up for the idea for The Face of the Deep (the series name for the two novels) back around 2003. It took about five years of writing to get about a third of the way done on this one book, which at the time was called Commissioned. Being a reporter, writing was often the last thing I felt like doing when I got home from work â I didnât even want to look at a keyboard. But a, shall we say, forced change in employment got me into another career path â libraries â that not only exposed me to more books but also gave back the desire to write when not at work. Suffice it to say that nine months after I lost my job and started working at our local county library, I finished Commissioned.

Then came the query letter, the submissions, the rejections. Iâm thankful that this phase only lasted about five months. During that time I happened upon the website for the fledgling Marcher Lord Press, and was intrigued by Jeff Gerkeâs ideas. He read my submission after it was recommended to him â read more of that backstory here â and eventually offered me a contract in July 2009.

Of course, my book was far too long â like 170,000 words. And thatâs where the real work began.

ESB: Somehow I was not surprised to learn that you originally intended your first two novels to be a single book. During the editing process, how did the decision to split them come about, and how did you feel regarding the change?

Steve: Funny â when Jeff asked me to cut the book in half, I was mortified. For maybe a minute or two. Then I said, âOK, either I cut it in half and get two books published, or I donât and maybe donât get published.â No-brainer there!

Finding a place to cut was easy. Making the alterations â the massive edits, the additions and subtractions, the finessing of the rough manuscript into something halfway readable â that was the great lesson. And Iâm indebted to Jeff for showing me the ropes in such a swift manner.

ESB: You said here that one of your goals is to remind readers of the hope of redemption. Iâm curious also what unique, specific spiritual themes underlie the stories of The Face of the Deep â perhaps some that arenât in other novels?

Steve: Well, I canât speak as to whether they are in other novels or not. But my major theme is that, as the Bible says, âFor the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing to the division of soul and of spirit, of joints and of marrow, and discerning the thoughts and intentions of the heart.â I hope my books show that by describing how a simple book â through the power of Godâs Holy Spirit, of course â can profoundly alter a personâs life.

ESB: Also, I am curious about one element of The Face of the Deep series â the story-worldâs mode of interstellar travel. One would think they had all been used up by now, but I canât recall a previous fiction parallel to sundoors. How did you come up with the concept, and what inspired or motivated its creation?

Steve: Ah, the sundoors. Also known as tract shifts. Youâre the first to ask me that one. Well, I confess thereâs a lot of âhandwaviumâ at work here. When I was deciding on a good interstellar transport system, I ruled out warp drive and hyperspace as too easy â you know, jumping to light speed at the last second to avoid the baddies. But I really liked the Alderson system used in The Mote In Godâs Eye and the gates in Babylon 5. Â So I took bits of both and some of my own ideas to cobble together this notion of gravitational distortions close to stars that actually form connections with other star systems. One well-placed quantum singularity later, and poof â thirty light-years traversed in a wink.

I mostly decided on that system as a way to keep space battles and pursuits tied to the âgeographyâ of solar space.

ESB: Finally, letâs imagine God gives you great power, with great responsibility, for a day. Youâre able to change one to three characteristics of current Christian fiction, including readers, authors, or publishers. What might you do with it?

Steve: Nice Spidey reference. Peter Parker is proud, I think ⌠seriously, though, I would likely change these three things:

- Readers would see the merit of sci-fi as much as they see the merit in historical romance.

- Authors would stop worrying about how they can best attract âsecularâ or non-Christian readers to their work and just write what they want to write the way they want to write it.

- Publishers would be willing to take more risks, to diversify their offerings to hungry readers, and not be so concerned about the bottom line that good fiction is lost.

ESB: Thanks much for your time, Steve, and Iâm sure many of us anticipate your forthcoming fiction. Godspeed to you and yours!

Steve: Thank you, Stephen, for the opportunity to address a new audience. And keep up the good work here at Speculative Faith.

A month ago, I was deep in the woods of Michiganâs beautiful Upper Peninsula, serving my yearly stint as âcamp pastorâ for a group of 7th and 8th grade church kids. We (the campers, staff, counselors, and myself) had the precious opportunity to get away from it all for seven days, to a place where your cell phone canât get a signal, but your sense of wonder at Godâs eternal power and divine nature is at four bars. Look around and youâll see evergreens, birch trees, a crystal clean lake, and a dozen quaint little cabins, each with a sentimental name like âSunset Bay.â

A month ago, I was deep in the woods of Michiganâs beautiful Upper Peninsula, serving my yearly stint as âcamp pastorâ for a group of 7th and 8th grade church kids. We (the campers, staff, counselors, and myself) had the precious opportunity to get away from it all for seven days, to a place where your cell phone canât get a signal, but your sense of wonder at Godâs eternal power and divine nature is at four bars. Look around and youâll see evergreens, birch trees, a crystal clean lake, and a dozen quaint little cabins, each with a sentimental name like âSunset Bay.â

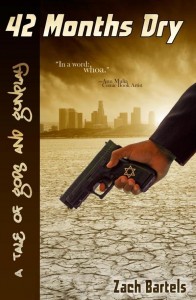

Zach Bartels is a pastor, an author, and an award-winning Bible teacher. He currently serves a church in Lansing, Michigan, where he lives with his wife Erin and their son. He holds degrees from Cornerstone University and Grand Rapids Theological Seminary.

Zach Bartels is a pastor, an author, and an award-winning Bible teacher. He currently serves a church in Lansing, Michigan, where he lives with his wife Erin and their son. He holds degrees from Cornerstone University and Grand Rapids Theological Seminary.

Steve: Letâs get the confession out in the open â I am a devoted adherent to space opera. Thatâs the sect of sci-fi thatâs always drawn me. Thereâs just something fantastic about these gleaming starships that whisk you to any corner of the universe, whether itâs off to an exotic world on a mission of exploration, or into the heart of enemy space to defeat the evil empire. I think I also admired the optimism of sci-fi that said yes, we can survive beyond this troubled and rapidly changing century-and-a-half on Earth.

Steve: Letâs get the confession out in the open â I am a devoted adherent to space opera. Thatâs the sect of sci-fi thatâs always drawn me. Thereâs just something fantastic about these gleaming starships that whisk you to any corner of the universe, whether itâs off to an exotic world on a mission of exploration, or into the heart of enemy space to defeat the evil empire. I think I also admired the optimism of sci-fi that said yes, we can survive beyond this troubled and rapidly changing century-and-a-half on Earth.