This article draws from two previous posts

from my personal blog that discussed nanites. The purpose of talking about nanites here isn’t just about the nanites per se, but also to illustrate how thinking about “Hard Science Fiction” notions can inspire unconventional story worlds. While it’s true that many readers of speculative fiction are more impressed with characters in settings that resonate with things familiar to us with a bit of a twist, which in a futuristic setting will probably veer them in the direction of space opera, the real world has dramatically changed many times because of advances in technology. And likely will change dramatically again (God willing our society continues to exist…). Thinking about nanites and how they are likely to affect the space travel, space combat, and aliens is just one means to create a story setting unlike what most science fiction (or speculative fiction) is doing.

This post is mostly science-fiction related, but if you bear with me, I’ll make a fantasy application.

What’s a nanite, anyway?

According to Wikipedia (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanite), the word “nanite” is just one of several words used to describe very small machines. Â Research is underway to create such machines, continually making operating devices smaller and smaller.

Of course, as of now, nanites right now are nowhere near as small as they can be in theory. Â In theory and in the realm of science fiction, a fully-functioning machine could be so small as to be tinier than the smallest bacterium. Â And these tiny machines could be designed to reproduce themselves automatically, which over time would allow enough of them to form to accomplish almost any purpose.

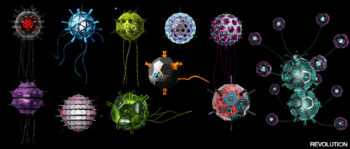

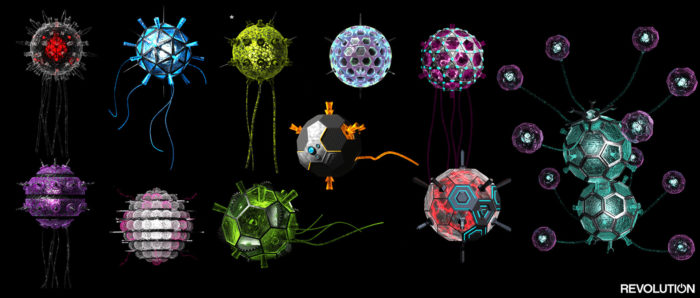

Nanites envisioned.

From: https://revolution.fandom.com/wiki/Nanites

Spacefaring nanites

A machine that small would be an ideal candidate for interstellar space travel from a realistic or “hard science fiction” perspective. Why?

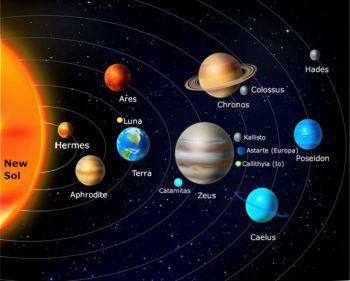

Because the most straightforward approach to travel to other stars is to simply go through space as fast as possible, the closer to the speed of light, the better.  Light in a vacuum moves at around 186,000 miles per second, roughly 6 trillion miles a year.  Even so the closest star system is over four years away at such a speed.  So any velocity significantly short of light speed involves waiting a long time to get anywhere.

To science fiction fans, there’s nothing new in what I just said. Â But by means of numerous stories featuring starships routinely cruising up to light speed or going into hyperdrive/warp drive or warp gates/wormholes, fans may have been lulled into thinking that getting a spaceship up to the speed of light is relatively easy, given the right energy source. Â It actually isn’t. (Nor are warp drives or wormholes easy–both require a type of matter that has never been shown to exist, something with negative mass, which would be very strange and probably isn’t real.)

A realistic design to get a spacecraft up to 92% the speed of light, the theoretical Project Valkyrie (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Valkyrie), would involve a craft weighing only 100 tons, far smaller than the starship Enterprise. Â Even so, the estimated amount of antimatter required to get this craft up to speed, just one time, is another 100 tons! Â So half the weight of the craft would be antimatter fuel…and antimatter happens to be the single most expensive substance humans can manufacture (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antimatter#Cost). Â Making 100 tons of it is completely beyond even the most outlandish of human plans (science fiction writers get to skip this messy detail and simply assume we’ve already got a pile of antimatter somehow).

On the other hand, a nanite, being so small, is much easier to get up to light speed. Â In fact we’ve got particle accelerators right now that move ions of heavy elements like gold up to speeds approaching that of light (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relativistic_Heavy_Ion_Collider).

Nanite space explorers

So we can imagine perhaps in the not-too distant future, someone could assemble a particle accelerator designed to hurl nanites out to the unknown reaches of interstellar space fast enough to arrive at other stars in a matter of years instead of centuries. Â Once there, the nanites in theory could use magnetic fields to slow down and land somewhere around another star. There they could reproduce from elements they find wherever they land and eventually assemble themselves into a larger machine, one that could perhaps beam back pictures to us of the new worlds they’re exploring.

Even if a futuristic civilization had warp drive or hyperdrive or star gates or whatever, putting a particle accelerator out in space and shooting forth tiny machines at near-light speed would be much cheaper in terms of energy costs in relation to a realistic Starship Enterprise that it would seem every advanced civilization would use nanites or very small probes in this way. At least with stars nearby them, sending out hordes of tiny machines in all directions seems a really good idea. It would be an excellent way to explore the stellar neighborhood.

Nanite space weapons

Here’s a problem with my thought of exploration–isn’t it true, historically speaking, that harnessing forces to destroy is easier than wending the forces of nature to build? Â It’s easier use fuel and air to make a bomb than it is to make a jet engine; it’s easier to split the atom to destroy Hiroshima than it is to build an atomic power plant.

If we could accelerate nanites to other worlds to build probes, it would be even easier to send them on a mission to destroy, to consume all life they encounter, to seek out compounds from living bodies to reproduce swarms of new nanites. Â This idea has the potential to change a lot of science fiction. Â Having trouble with the Klingons? Â Simply fire some flesh-eating nanites at their home world…

Independence Day, the movie that features massive alien spaceships cruising through our atmosphere and blasting us with energy beams, would have it all wrong. Â The aliens would instead land on the planet with tiny particles too small for us to detect. Â These nano invaders would reproduce and reproduce, eating life on a small scale at first. Â Before they were even visible to the naked eye there would be billions of them, able to continue killing if even one of them survived any attempt to destroy them with radiation or chemicals. Â Our military would be useless, our medicines inadequate. Â Before long, all of mankind would be enveloped in a continually self-replicating tide of tiny devouring machines…

Note that even if you don’t want to see the future like this, even if you prefer starships in classic fleet battles in deep space instead, nanite weapons would still make a lot of sense as a supplement to starships. Starships could shoot nanites at one another and thus would have to incorporate anti-nanite defenses. Or even fire microprobes from an accelerator when it came time to explore unknown areas unsafe for the ship. Or there could be a “mine field” of nanites, floating freely in space, looking like ordinary dust particles, until they affixed themselves to the hull of the ship (as I mentioned in a previous post on Speculative Faith about space weapons)…or nanites could even provide stealthy means of communication or conveying information. Or as spying devices!

Nanite anti-nanite defense

Imagine that nanites become such a part of future warfare that it becomes standard to get a nanite “vaccination” of helpful nanites, whose job is to repel any hostile nanites who might invade your body. Such nanites could have many other benefits. They could enhance healing and clear out harmful plaques in the arteries and brain. They could perhaps undo aging, at least in part. They could assist your assimilation into the Borg Collective (OH WAIT THAT’S NOT A BENEFIT đ )

Anyway, my idea of what’s funny aside, it could be that for many reasons, having nanites throughout your body is an ordinary thing in some highly advanced futuristic society. Maybe they’d even eliminate bacteria and viruses, making people free of communicable diseases. Though that might cause another problem.

Nanite-infested aliens

Inspired by the history of Europeans coming to the New World carrying bacteria to which the native inhabitants had little to no immunity, I thought: “What if aliens visiting Earth carried their own sort of infection or infestation, to which we humans had no immunity?” Sort of a War of the Worlds scenario in reverse…

That sort of thing has already been done, aliens carrying virulent disease(s) humans don’t carry. But what if the infestation were of nanites–what if nanites become a standard part of healthcare for any advanced technological species, for reasons I’ve already suggested? (Just as mask-wearing and hand washing and social distancing have recently become important to modern life.)

To the degree that nanites are literally crawling all over (and inside) the bodies of high-tech aliens–or perhaps time travelers from Earth’s distant future. What if these nanites potentially posed a risk to the human race?

It could be of course that nanites would be programmed in such a way as not to harm us, but what if the standard way nanites were kept from invading another creature’s body would be by your own nanites?

When hypothetical aliens of this type contact one another, the nanites on a particular alien’s body intended to be there would always outnumber those that would accidentally cross over from contact with someone else. The ones designed to be on a particular body could have a swarm and hive mentality–effectively collaborating to defend the host and keep any outside nanites from making any trouble.

But for us human beings, our immune systems are not designed to fight machines. We would have no immunity at all. Casual contact–a handshake, such as in the Star Trek movie “First Contact,” would at first seem to have no ill effect at all. But eventually, perhaps in a few days, Dr. Cochrane would find the skin on his hand begins to sluff off…and his arm begins to swell…in a week, the pain is unbearable and is all over his body. In ten days, he is dead…but everyone he touched and everyone who touched him in the meantime is infested by tiny robots that reproduce wherever they are and which attack whatever does not mach their original host. Leaving everyone totally defenseless…

Nice guy alien nanites versus alien invaders

Actually, nice guy aliens who meet us on purpose would either find a way to shut down their own nanites or would refrain from touching us if they were nanite-infested. But what about alien invaders? Will Smith in Independence Day punches an alien in the face…what if he found that within hours his knuckles began to blister…and per the original story, the virtually impossible uploading-of-a-virus-on-a-completely-unknown-computer-system still works, the shields go down, the aliens get blown up. But pilots first, in droves, then every person they know, then probably the entire human race, find themselves dissolved bit by bit by tiny little machines that don’t scrub out or bleach out well enough, that radiation can’t entirely eliminate, and which aren’t even intended to be a weapon. War of the Worlds, in reverse.

Accidental nanite infestation

The most interesting for this kind of story might be an accidental encounter. Say a crash landing on our planet. Or an alien space vessel sends a mayday and nearby humans (who’ve never encountered aliens before) fly a spaceship or starship over to help. Neither the humans nor the aliens would know what the disastrous results to humanity will be. The humans because they don’t know the aliens carry nanites–and the aliens because they don’t realize we humans don’t…

But our heroes, of course, will figure out way to shut down the nanites. Perhaps with help from the future–or from “nice guy” aliens.

Nanites for fantasy fans

So what’s all this to a fan of fantasy? You aren’t interested in starships and eating metal and all that crap. For you, if it isn’t magical, it’s no fun–okay, first off you and I are clearly different, right? But anyway, I do have something for you.

Let’s say a fantasy world is inhabited by tiny creatures. Say microscopic pixies. Imagine a fantasy world in which the microscopic pixies are tamed (through the proper use of magic, of course) and are swarming over a wizard’s body like nanites over aliens. Or are used as weapons, mines, spies, and are sent out in vast numbers. Etc. The same ideas as written here, or similar, but with a fantasy twist (such as the nanite/pixies have a will of their own…)

Conclusion

Nanite types: Copyright Linden Stirk

There are of course plenty of science fiction stories that feature nanites, most famously probably Star Trek has them as part of what makes the Borg Collective who they are. But really in the Star Trek universe everyone should have and use nanites, Federation, Klingons, Romulans, etc. They’re such a relatively inexpensive solution to many problems.

They’re cheaper to launch into space than full-sized explorers, making them better offensive weapons and explorers. They could also be part of stationary defenses, spy gear, commo gear, and healthcare. They could become so standard that futuristic humans or aliens would be unable to imagine a species without them–which could prove disastrous for the human race. Or other species.

So what are your thoughts on this topic? Do you have favorite stories featuring nanites? Is any one aspect of the way nanites could be used more interesting to you than the rest–if so, what would that be? Any other comments?

should stop. You should not use the phrase a pair of twins because that is, you know, how twins work. Itâs not necessary to state that some famous person has written an autobiography of her life, because she scarcely could have written an autobiography of anyone elseâs life. A biography of his life is likewise unnecessary but more forgivable. All moments are brief, and all summaries should be. A warning that isnât advanced isnât. Cooperate together is repetitive because one cannot cooperate alone. The phrases added bonus and free gift are simply not acceptable.

should stop. You should not use the phrase a pair of twins because that is, you know, how twins work. Itâs not necessary to state that some famous person has written an autobiography of her life, because she scarcely could have written an autobiography of anyone elseâs life. A biography of his life is likewise unnecessary but more forgivable. All moments are brief, and all summaries should be. A warning that isnât advanced isnât. Cooperate together is repetitive because one cannot cooperate alone. The phrases added bonus and free gift are simply not acceptable.

Only the allusion of a “quirky” angelic guardian gives a suggestion of the humor contained in the book, but by looking at the reviews, a potential buyer can quickly see that humor is a significant part of the booK:

Only the allusion of a “quirky” angelic guardian gives a suggestion of the humor contained in the book, but by looking at the reviews, a potential buyer can quickly see that humor is a significant part of the booK:

Here’s a clip from

Here’s a clip from

Basically tension comes from any type of struggle. Sometimes the struggle is external and those seem easy to identify. But they need to be genuine struggles. Too many superhero movies lack tension because there is no question about the outcome. The superhero will come out on top because, you know, superpower. That’s why superhero authors often create supervillains to confront the heroes—they want to make the struggle credible. They want to open the possibility in the viewer’s mind that the hero might lose. They want their story to have tension.

Basically tension comes from any type of struggle. Sometimes the struggle is external and those seem easy to identify. But they need to be genuine struggles. Too many superhero movies lack tension because there is no question about the outcome. The superhero will come out on top because, you know, superpower. That’s why superhero authors often create supervillains to confront the heroes—they want to make the struggle credible. They want to open the possibility in the viewer’s mind that the hero might lose. They want their story to have tension. All that to say, writers need to evaluate their own scenes based on whether there is tension, high or low. Varying the level of tension is not bad at all, but a consistent story with scene after scene of low tension simply won’t hold a reader’s interest.

All that to say, writers need to evaluate their own scenes based on whether there is tension, high or low. Varying the level of tension is not bad at all, but a consistent story with scene after scene of low tension simply won’t hold a reader’s interest.