Spec Faith To Partner With Christian Geek Central

Hello SpecFaith readers!

Hello SpecFaith readers!

My name is Paeter Frandsen, and I help run the website and community at Christian Geek Central.

Stephen Burnett has graciously invited me to introduce myself here, and also to take a moment to let you know about an exciting partnership coming up between SpecFaith and Christian Geek Central.

I’ve been a geek since before I knew what a geek was and long before anyone thought being a geek was “cool.” But what is a geek, really? It’s become hip to claim geek status in some circles, while others shy away from the label. I use it as an affectionate term of endearment, although I don’t think being a geek is “cool.”

The word finds its origins in old carnival circles, where a “geek” was a performer showcased for doing morbid or disgusting things, like biting off the head of a live chicken. Later, this word was applied as an insult to those who were considered strange or unusual. So, despite the fact that many interests and activities that were once “geeky” are now popular, to my mind the word “geek,” properly used, describes someone who is considered unusual or strange in some way. We probably all have little oddities that make us just a little bit “geeky.” But to the degree that someone is “geeky,” they are also “strange and unusual” in the eyes of those around them.

In my experience, and maybe in yours too, the Church has trouble knowing how to relate to geeks. On her best days she says, “We love you, but we don’t really know what to do with you.” And on her worst days she says, “What you enjoy is evil and you need to repent to have a place in our community.”

I’ll be the first to tell you that there are things floating around in the world of geek entertainment that are worth repenting of. And I think the Church is slowly figuring out how to biblically discern the difference between genuine evil and harmless (even God-honoring) imaginative entertainment. But there are plenty of sectors in Christendom that are still slow to go back to their Bibles in order to really sort through these issues with both an uncompromising pursuit of truth and gracious, undeserved portions of love.

This situation leaves us with fans of geek entertainment who hesitate to be involved in their local churches, and local churches who have little practice in befriending and incorporating geeks. For this to change I think we need at least two things to happen. First, the Church, as I mentioned, needs to get back into scripture and learn how to better discern her way through entertainment and develop the application of grace to relationships. Second, geeks need to stop waiting for the Church to change and just get back into the mix. Yeah, that will get messy sometimes, and people will get hurt. But the Church is incomplete without geeks, who have the potential to bring blessings that I’m convinced would amaze many Christians.

In my time spent with other geeks, and in looking deeply into myself, I’ve noticed some character traits and tendencies that a lot of geeks have in common. People are very complex, and so not all geeks share all these traits or possess them to the same degree as others. But common patterns I’ve seen in geeks include introversion, intelligence, awkwardness, creativity, insecurity, imagination, selfishness, and an appetite for learning. Those are just a few for starters, and as you can see, it’s a mixed bag.

Now, imagine a “prototypical” geek with all of those traits who increasingly engaged in purposeful community with Christ and other believers. What you’d see happen over time would be the steady destruction of those negative traits and the spiritual empowering of the positive ones. Imagine a person like that applying themselves to caring for others in their pain. Many geeks are all too familiar with pain and would be a wonderful companion for those in the middle of it. Imagine a geek helping friends in a small group understand the more complex issues of scripture, because his love for world-building or crazy concepts in fantasy novels one day awakened a love for understanding biblical history or the complex issues of biblical doctrine!

The sanctified geek has enormous and unique potential that I long to see in action among our churches. And so I have dedicated my life and ministry to equipping, encouraging, and inspiring Christian geeks to live more and more for Christ. In both myself and those in the CGC community, I hope to see increasingly uncompartmentalized living, in which we both celebrate and examine geek entertainment from a biblical perspective, and do the same as we look at both the good and bad traits that come with being a geek.

About a year and a half ago I launched the Christian Geek Central Youtube channel as a companion to our website. My hope for Christian Geek Central has always been to add more and more voices aside from my own—voices that have a high view of scripture and a love for “geeky” entertainment.

About a year and a half ago I launched the Christian Geek Central Youtube channel as a companion to our website. My hope for Christian Geek Central has always been to add more and more voices aside from my own—voices that have a high view of scripture and a love for “geeky” entertainment.

A few months later I discovered SpecFaith and immediately became excited over the kind of thoughtful content produced here. I noticed that SpecFaith did not have a presence on Youtube and almost instantly saw potential for a God-honoring partnership. After talking with Stephen Burnett he seemed to see the same potential.

Going forward, you can expect to see video versions of select articles from SpecFaith on Christian Geek Central Youtube, as well as embedded here at SpecFaith. (Fear not! They will still be published here in text form first!) Our hope is that an entirely new audience will benefit from the content at SpecFaith and be drawn to what is happening both here and at Christian Geek Central.

I hope you’ll look forward to both experiencing and sharing SpecFaith content in a new way. And if you’re ever inclined, please stop by Christian Geek Central and say hello! You’ll find myself and a number of other geeks there who would love to connect with you more as we endeavor to both “geek out and seek the truth!”

The first myth may be that Christian stories spend all or most of their time John 3:16-ing the reader. No, they donât.

The first myth may be that Christian stories spend all or most of their time John 3:16-ing the reader. No, they donât. The second myth may be that Christian novels usually spell out the gospel. Often they donât.

The second myth may be that Christian novels usually spell out the gospel. Often they donât.

Should Christian fiction evangelize?

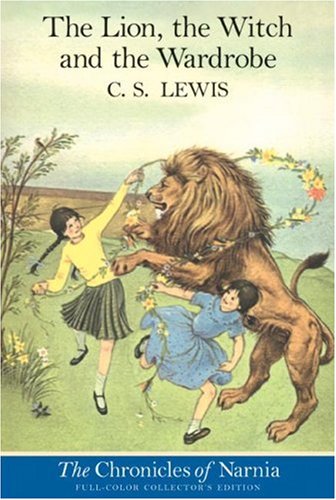

Should Christian fiction evangelize? Secondly, I say NO to the idea that Christian fiction ought to evangelize in this way because I don’t believe it’s even possible to write a story that, by itself, can lead a non-believing reader to salvation. Ideas and allusions that seem obvious to an author steeped in Biblical language and symbolism often go whizzing past a reader who isn’t actively looking for them — consider all the children and even adults who’ve read The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe without ever realizing that Aslan is a Christ figure, or indeed that there is anything Christian about the book at all. Even the Gospels themselves are frequently misunderstood and misinterpreted by people reading them for the first time, so do we really think we’re going to do better with fiction?

Secondly, I say NO to the idea that Christian fiction ought to evangelize in this way because I don’t believe it’s even possible to write a story that, by itself, can lead a non-believing reader to salvation. Ideas and allusions that seem obvious to an author steeped in Biblical language and symbolism often go whizzing past a reader who isn’t actively looking for them — consider all the children and even adults who’ve read The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe without ever realizing that Aslan is a Christ figure, or indeed that there is anything Christian about the book at all. Even the Gospels themselves are frequently misunderstood and misinterpreted by people reading them for the first time, so do we really think we’re going to do better with fiction?

October 31—what’s the first thing that comes to your mind?

October 31—what’s the first thing that comes to your mind?

The whole concept of secular and sacred art, despite my growing up reading mostly Christian fiction, was foreign to me until college, when I entered the debate and began studying it for myself. The more I listened, the more I observed, the more I realized that there is, in fact (or, at least, has been) a strange disconnect between American Christianity and American culture (and therefore art) for some time.

The whole concept of secular and sacred art, despite my growing up reading mostly Christian fiction, was foreign to me until college, when I entered the debate and began studying it for myself. The more I listened, the more I observed, the more I realized that there is, in fact (or, at least, has been) a strange disconnect between American Christianity and American culture (and therefore art) for some time.

Such idolatry takes endless forms. Writes Tim Keller in his excellent treatise Every Good Endeavor:

Such idolatry takes endless forms. Writes Tim Keller in his excellent treatise Every Good Endeavor: The rapturous gravity of this moment is approached by C.S. Lewis in his sublime essay The Weight of Glory:

The rapturous gravity of this moment is approached by C.S. Lewis in his sublime essay The Weight of Glory: