Zachary D. Totah—Zac to his friends—is the newest Spec Faith contributor. His articles will appear every Tuesday, starting tomorrow. In order for our visitors to get to know Zac some, we put together an interview.

Zachary D. Totah—Zac to his friends—is the newest Spec Faith contributor. His articles will appear every Tuesday, starting tomorrow. In order for our visitors to get to know Zac some, we put together an interview.

RM: Zac, tell us a little bit about your background—where you grew up, your family, what’s your day job, if you have one.

ZDT: Iâve lived in Colorado my entire life, mainly in Parker, a suburb of Denver. Weâre in a neighborhood, but everyone has around three acres of land and the roads arenât paved, so friends have joked we live in the middle of nowhere. Even though weâre only five minutes from âcivilization.â

Iâm the oldest of four kids (a sister and two brothers). My parents homeschooled us all the way through, and my sister and I have graduated. My siblings and I love to play sports, and my sister, second-youngest brother, and I are in a D3 hockey league. Everyone is a huge sci-fi and fantasy fan, and we love books and movies. Traveling was a big part of life for a number of years. Vacations ranged from Lake Louise and Banff in Canada to New England to Florida.

My day job is writing . . . sorta. I donât get paid for it, but I spend a lot of time on stories and blogging. Iâm earning a Communications degree through an online program, so that takes up a big chunk of time.

RM: Ah, growing up in Colorado! đ (Yes, that’s where I was born. My family still has some mountain property there.) How great that you enjoyed speculative fiction with your family. I can see why you’ve chosen the genre for your own writing. But Christian? Tell us about your faith journey. Did you grow up going to church?

ZDT: Both my parents are Christians, so I grew up going to church and hearing about God and Jesus. In my younger years, it was more of a distant thing. I made profession of faith when I was sixteen, but itâs only been in the past four years, after coming out of a legalistic environment, that Iâve come to appreciate the comfort of the Gospel and the importance of right doctrine.

RM: Praise God you came out of the legalistic environment with your faith intact. A lot of people don’t. But turning a page, what one thing would people be surprised to learn about you?

ZDT: Only one? Well . . . I like shopping. For books, obviously, but also for clothes. Which mainly consists of admiring all the things I want to buy and knowing I donât have the money for it.

RM: I can relate! About the books and the admiring things I don’t have money to buy. But since you mentioned books, describe your journey as a novelist. What got you started writing, who influenced you, what are your aspirations?

ZDT: I actually wrote a blog post that partially answers this—and includes parallels to Lord of the Rings. As writers go, I was a late bloomer. I didnât take any interest in writing until I was seventeen, when one day an idea popped into my head and I decided to turn it into a story. Havenât looked back since. A couple early influences were Tolkien and Lewis. I know, standard answer. Seriously, though, they are amazing. More recently, Iâve been blown away by Brandon Sanderson. I want to write like him when I grow up. đ

In terms of teaching influences, Jeff Gerke is probably at the top. Iâve read most of his craft books, and Iâve had the privilege of meeting him in person, twice at Realm Makers and twice for lunch—since we live only an hour apart.

Of course winning awards and making a living off my books would be great, but for me, the main ambition is to share the joy of stories with others. My goal with storytelling is to connect with people on a meaningful level by telling stories infused with imagination that shed light on truths such as redemption, sacrifice, and loyalty in a way thatâs compelling and inspiring.

RM: No doubt about it: Lewis and Tolkien influenced a lot of us. But I wouldn’t call you a late bloomer. I mean, I didn’t start writing fiction until I was well into adulthood. I’d been teaching for nearly twenty years. I guess that’s the great thing about writing: no age limit!

We’ve already touched on this, but why don’t you expand some: why do you write speculative fiction instead of contemporary or historical or suspense or whatever else you might have chosen?

ZDT: Honestly, I canât put a finger on exactly why I got started writing spec-fic. Again, books Iâd read when I was younger played a part, but itâs only been more recently that Iâve figured out I love the sense of being transported. My tagline is Imagine, Dream, Explore, a condensed version of imagine the impossible, dream the unbelievable, and explore the uncharted. That sense of transportation to another planet or world, the thrill of knowing anything is possible, is the heart of spec-fic to me and I canât get enough.

RM: Wow! I’d like to bottle that answer. Awesome tagline, especially the expanded version. And to be honest, I can’t get enough either, particularly of fantasy. And particularly of a specific kind of fantasy. So what is your favorite speculative novel of all time (Christian or secular) and why is that your favorite?

ZDT: Oh dear. Thatâs like asking a parent to choose a favorite child. If I had to pick one, Iâd go with Words of Radiance by Brandon Sanderson. Itâs incredible on many levels. Diverse characters, awesome magic systems, fascinating cultures, cool settings, imaginative creatures, complex plot lines, portents of world-changing doom, intense battles, court intrigue, philosophical musings, probing themes, mysteries and surprises aplenty. Everything epic fantasy should be. So. Much. Yes.

ZDT: Oh dear. Thatâs like asking a parent to choose a favorite child. If I had to pick one, Iâd go with Words of Radiance by Brandon Sanderson. Itâs incredible on many levels. Diverse characters, awesome magic systems, fascinating cultures, cool settings, imaginative creatures, complex plot lines, portents of world-changing doom, intense battles, court intrigue, philosophical musings, probing themes, mysteries and surprises aplenty. Everything epic fantasy should be. So. Much. Yes.

RM: OK, OK, I’m sold! I’m checking out Words of Radiance as soon as possible! But you’ve written epic fantasy, too. Tell us a little about The Skyriders Series.

ZDT: This is actually the fourth series Iâve written, but itâs the first one I feel was decent from the get-go. Itâs a cross between Sword & Sorcery and High Fantasy. Four books total, though Iâve only completed the first two and they still need loads of editing (doesnât everything?). The main feature is a worldbuilding one. A perpetual layer of cloud exists and is like the surface of the ocean. Below is a typical fantasy world, with the Nine Kingdoms of Kadriath playing the central role. Above, however, are mountain peaks and stone formations that poke through the clouds like islands, where another world exists. The two worlds have legends and tales of the other (as well as a complex history) and end up meeting and clashing.

The two main characters in the series are Alya, a princess outcast from Kadriath, and Elior, a Skyrider from the Sky Realm, called Azurin.

The first book is mainly Eliorâs story, as he tries to stop a Skyrider from destroying the order while working to overcome fears and doubts stemming from his past. Iâm reworking it slightly so it ties more directly into the second book.

The second book expands significantly and follows both the Nine Kingdoms, which the Skyriders call the Underland, and Azurin, primarily through the two points of view, Alya and Elior as they try to prevent an enemy army from conquering the world at the bidding of their gods.

The details for books three and four are still shady. What I have so far is that the third book builds on the outcome of the second book, and likewise the fourth book builds on the third, and to some extent the second. Some characters become more important, thereâs a search for a Skyrider artifact called the Lifestone, catastrophes loom, and Alya and Elior sail a turbulent sea that tests them mentally, physically, and emotionally.

RM: What an intriguing world! I know this is a series I’m going to enjoy. But what, if anything, about your work is distinctly Christian?

ZDT: In my fantasy worlds, Iâve always included some notion of God. Itâs not obvious every time and sometimes doesnât directly impact the main characters. Iâve noticed I tend to write redemptive or sacrificial themes as well. And sometimes there arenât any Christian elements, veiled or otherwise. It depends on the story.

RM: So I take it you’re not aiming exclusively to be published by a traditional Christian publisher. Fill us in about what you’re working on now.

ZDT: I put editing the first book in the Skyriders Series on hold so I could focus on school, but Iâd like to get back to it soon. In the meantime, I just started posting installments of a novella called The Time That Was Not on my blog. I recently wrote a flash fiction story for Splickety Magazineâs Havok imprint that didnât make the cut, so Iâm deciding whether Iâll tweak it and submit somewhere else or post it on my blog.

I have a couple ideas simmering that might turn into short stories or novellas. And Iâve considered writing flash fiction for each edition of my soon-to-launch newsletter. In short, too many ideas and not enough time.

The ultimate goal is to publish my novels. If I can find homes for some of my shorter works, that would be great, but I also like the idea of putting them on my blog or in my newsletter—because who doesnât love free stuff?

RM: Interesting. I recently read an article about content marketing which addresses that very idea. With all the “too much to write and not enough time, what makes writing a challenge? A joy?

ZDT: The challenges: Finding the time to write. Dealing with doubts and wondering if my efforts are in vain. Putting to death my perfectionism so I can actually move forward instead of obsessing over every little detail. Procrastination. EDITING.

On the positive side, I love crafting plots and creating characters and worlds. Writing is a great outlet for my creativity. Coming up with ideas is also addicting. Itâs also cool to look back over something Iâve written and think, âWow, I actually like this.â At the top of the list is the ability to share stories with people. Having people read and enjoy what Iâve written is the best reward.

RM: I suspect you’re going to experience a lot of that reward here at Spec Faith, Zac. But let’s not limit them to this venue. How can visitors find and follow you elsewhere on the web?

ZDT: Um, hop in a TARDIS?

Kidding aside, Iâm most active on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, and Iâm also on Instagram and Goodreads. Of course, Iâd love to have more visitors to my website. If youâre into sci-fi or fantasy, I think youâd enjoy my posts.

RM: I couldn’t agree more. Thanks so much for sharing with us, Zac.

Zachary D. Totah—Zac to his friends—is the newest Spec Faith contributor. His articles will appear every Tuesday, starting tomorrow. In order for our visitors to get to know Zac some, we put together an interview.

Zachary D. Totah—Zac to his friends—is the newest Spec Faith contributor. His articles will appear every Tuesday, starting tomorrow. In order for our visitors to get to know Zac some, we put together an interview. ZDT: Oh dear. Thatâs like asking a parent to choose a favorite child. If I had to pick one, Iâd go with Words of Radiance by Brandon Sanderson. Itâs incredible on many levels. Diverse characters, awesome magic systems, fascinating cultures, cool settings, imaginative creatures, complex plot lines, portents of world-changing doom, intense battles, court intrigue, philosophical musings, probing themes, mysteries and surprises aplenty. Everything epic fantasy should be. So. Much. Yes.

ZDT: Oh dear. Thatâs like asking a parent to choose a favorite child. If I had to pick one, Iâd go with Words of Radiance by Brandon Sanderson. Itâs incredible on many levels. Diverse characters, awesome magic systems, fascinating cultures, cool settings, imaginative creatures, complex plot lines, portents of world-changing doom, intense battles, court intrigue, philosophical musings, probing themes, mysteries and surprises aplenty. Everything epic fantasy should be. So. Much. Yes.

For another exemplary exhibit, let’s return to the well. In The Lord of the Rings, when Frodo the Ringbearer — who’s been assaulted day and night by the lure of the Ring of Power — at last stands before the Crack of Doom, what happens? He falls. He cracks beneath the strain, caving in to temptation, and Middle-earth is saved in that moment only through the providential intervention of another ringbearer in thrall to sin.

For another exemplary exhibit, let’s return to the well. In The Lord of the Rings, when Frodo the Ringbearer — who’s been assaulted day and night by the lure of the Ring of Power — at last stands before the Crack of Doom, what happens? He falls. He cracks beneath the strain, caving in to temptation, and Middle-earth is saved in that moment only through the providential intervention of another ringbearer in thrall to sin. As Tim Keller writes in Every Good Endeavor:

As Tim Keller writes in Every Good Endeavor:

Author and former SpecFaith contributor Rachel Starr Thomson returns to showcase an excerpt from

Author and former SpecFaith contributor Rachel Starr Thomson returns to showcase an excerpt from

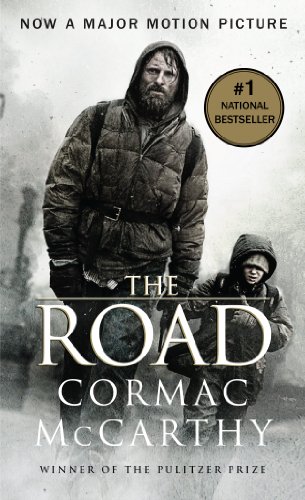

Any number of stories illustrate this, none less so than The Road by Cormac McCarthy, a post-apocalyptic novel (released in 2006 and made into a movie in 2009) about survival in which the protagonists determine they are the good guys. When the boy’s father dies, his hope then hinges on his father’s statement that after his death, his son can pray to him, and on the idea that the people he joins are also good guys.

Any number of stories illustrate this, none less so than The Road by Cormac McCarthy, a post-apocalyptic novel (released in 2006 and made into a movie in 2009) about survival in which the protagonists determine they are the good guys. When the boy’s father dies, his hope then hinges on his father’s statement that after his death, his son can pray to him, and on the idea that the people he joins are also good guys.

new heavens and the new earth. But again, this is a matter of the End Times in fiction, not in actual fact. I rarely find five minutes of happiness at the end of a book to be worth the long journey of misery leading up to it. C.S. Lewis, in The Last Battle, did manage to give the joys following the end of Narnia more impact than the end itself, but there are few like C.S. Lewis. (And, notably, the Narnian Apocalypse was played out on a relatively small scale.)

new heavens and the new earth. But again, this is a matter of the End Times in fiction, not in actual fact. I rarely find five minutes of happiness at the end of a book to be worth the long journey of misery leading up to it. C.S. Lewis, in The Last Battle, did manage to give the joys following the end of Narnia more impact than the end itself, but there are few like C.S. Lewis. (And, notably, the Narnian Apocalypse was played out on a relatively small scale.)

Speculative Faith uses a random quote widget that allows various sayings to appear at the top of each page. Some of the quotes are insightful, I think, and some thought-provoking. One which appeared some years ago, for me, was simply provoking.

Speculative Faith uses a random quote widget that allows various sayings to appear at the top of each page. Some of the quotes are insightful, I think, and some thought-provoking. One which appeared some years ago, for me, was simply provoking.

Pharaoh himself hardened his heart, but God used that act of defiance for His glory. Joseph told his brothers that they meant evil against him, but God meant what they did for good. Both these people and events show that the evil work of a person’s hands isn’t God-glorifying until God gets a hold of it and uses it as He wishes.

Pharaoh himself hardened his heart, but God used that act of defiance for His glory. Joseph told his brothers that they meant evil against him, but God meant what they did for good. Both these people and events show that the evil work of a person’s hands isn’t God-glorifying until God gets a hold of it and uses it as He wishes.