Motivate Kids To Read and Write!

I hated reading. I really didnât enjoy writing, and my grades reflected it. I wasnât exactly the prospect for becoming an author. Why did I need to read when I had Sonic the Hedgehog on Sega Genesis? There was always a new Sonic game and a more enhanced Dr. Robotnik to beat. Iâd sit for hours in my blue video rocker chair glued to that black controller, connected to my character through a five foot black cord.

I hated reading. I really didnât enjoy writing, and my grades reflected it. I wasnât exactly the prospect for becoming an author. Why did I need to read when I had Sonic the Hedgehog on Sega Genesis? There was always a new Sonic game and a more enhanced Dr. Robotnik to beat. Iâd sit for hours in my blue video rocker chair glued to that black controller, connected to my character through a five foot black cord.

Occasionally Iâd venture outside with my friends, but that addictive little blue hedgehog always called me back. I remember one of my friends trying to get me to read Louis Lamoure. I think I made it halfway through a chapter. Iâd skim the required reading books, and the grades on my book reports would prove it. In high school, my streak of “not reading” continued, and my writing reflected the minimum page or word count required to get a B or C.

It wasnât until college that I read a book because I wanted to. The series I chose is the sometimes hated, but mostly beloved, Harry Potter series. Now some of you reading this are already averting your eyes, and thatâs okay; thatâs your choice, like reading the books was mine. But let me tell you something the series did for me and many other kids like me: it got me excited about reading. We could debate the magic of the Harry Potter world as good, bad, etc., but the real magic about the books was the creative world that drew young readers in. My imagination was opened and the characters felt like friends. In fact, the series inspired me to become a writer. Before I talk about the writing thing, letâs take a bit of a tangent.

Now why did I decide to pick this series up? Well, I met this beautiful girl, and we challenged each other to see who could finish the entire book series first. The only title not out was Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. The only reason I was able to catch up to her was because we both had to wait for the release of the final book. So when it finally came out, we sat in a Borders bookstore (sadly they went the way of the dodo bird) and waited for the midnight release.

The next few days were devoted to reading as much as possible and I am proud to say I won. Now it is debated if my winning was completely above board or not and here is why. Early on in our competition, we went to a friendâs house for a nice home cooked Italian dinner. As we ate, I excused myself from the dinner table to use the restroom. As I passed my girlfriendâs purse I slipped out her copy of The Half Blood Prince and took it with me. Then I proceeded to read it for the next half hour; needless to say, my absence in the restroom for so long, was causing everyone else some concern, but no one checked, and I made quite a bit of ground on my reading. Now with that confession over, you can judge if I won or not. But I did indeed win in the long run because the girl married me!

So Harry Potter inspired me to read, and it also inspired me to write, but the writing thing is twofold. One, I thought how cool would it be to create my very own world, or at least my very own characters. And two, I want to write a book series that is a bit more ethical than Harry Potter. You see my real beef with the Harry Potter series is not the magic because, sorry to burst your bubble, but magic isnât real. My opposition to the series is the lack of an honorable hero. You see, though Harry appears to be a great hero, he sort of got there through a whole lot of lying, disobedience, and arrogance at times. To tell kids that Harry is a hero, when he overcame evil by committing many wrongs of his own, seems wrong. It’s like saying, Sure, little Billy, steal that candy bar as long as in the end you overcome a great trial. NO! WRONG!

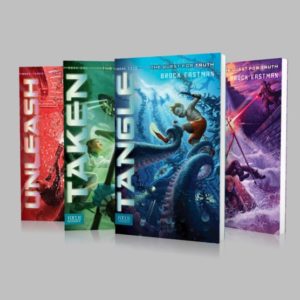

I wanted to give readers characters they could really look up to, characters they could learn from and trust. Something else I wanted to do, specifically for The Quest for Truth, was provide a story without unnecessary death. This wasnât a reflection of Harry Potter, but of many series for kids and young adults, and not just in the secular marketplace. How often do our kids read of a sword slicing through someone, or of a gun fight? We probably wouldnât let them watch such violece on TV, so why would we let them read it in a book?

So with the desire to provide authentic moralistic heroes and a storyline without unnecessary death, I began writing The Quest for Truth. And though this kid who hated reading and writing, hadnât read anything until he was in college, and hadnât written anything larger than a few thousand word research paper, wrote a 100,000 word manuscript with no prospect of getting it published. After all I was a college student in the middle of the cornfields of Illinois getting a degree in marketing. It wasnât until later that God opened up some pretty amazing doors.

The fact is God has His plans for us. Jeremiah 29:11 (ESV) says, “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope.”

So what are you waiting for? You just read this nearly 1000 word article; go read some books. Perhaps youâll be inspired to write some of your own!

Also at this time The Quest for Truth is specially priced on Amazon Kindle. Taken (book 1) is available for $0.99 on Amazon Kindle, Risk (book 2) is $4.99 on Amazon Kindle, Unleash (book 3) is $4.99 on Amazon Kindle and the latest release, Tangle (book 4) is $4.99 on Amazon Kindle. So grab your copies now.

– – – – –

Brock Eastman lives in Colorado with his wife, four kids, two cats, and leopard gecko. Brock is the author of The Quest for Truth series, the Sages of Darkness series, Showdown with the Shepherd in the Imagination Station series, and the novella Wasted Wood. He writes articles for FamilyFiction digital magazine and Clubhouse magazine. You may have seen him on the official Adventures in Odyssey podcast and on its Social Shout-Out. He was the first producer of and launched the Odyssey Adventure Club. Brock currently works for Compassion International, whose mission is to release kids from poverty worldwide. Brock enjoys getting letters and artwork from fans. You can keep track of what he is working on and connect with him at the following online venues:

Brock Eastman lives in Colorado with his wife, four kids, two cats, and leopard gecko. Brock is the author of The Quest for Truth series, the Sages of Darkness series, Showdown with the Shepherd in the Imagination Station series, and the novella Wasted Wood. He writes articles for FamilyFiction digital magazine and Clubhouse magazine. You may have seen him on the official Adventures in Odyssey podcast and on its Social Shout-Out. He was the first producer of and launched the Odyssey Adventure Club. Brock currently works for Compassion International, whose mission is to release kids from poverty worldwide. Brock enjoys getting letters and artwork from fans. You can keep track of what he is working on and connect with him at the following online venues:

Website: http://brockeastman.com

Twitter: @bdeastman

Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/eastmanbrock

YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/user/FictionforAll/videos

Pinterest: http://www.pinterest.com/brockeastman/

Readers may know that I try to push back against an impulse to speak more about âthe fiction industry.â Alas, that has potentially created the impression among some that I would rather never talk about things like a storyâs plot, dialogue, and originality.

Readers may know that I try to push back against an impulse to speak more about âthe fiction industry.â Alas, that has potentially created the impression among some that I would rather never talk about things like a storyâs plot, dialogue, and originality.

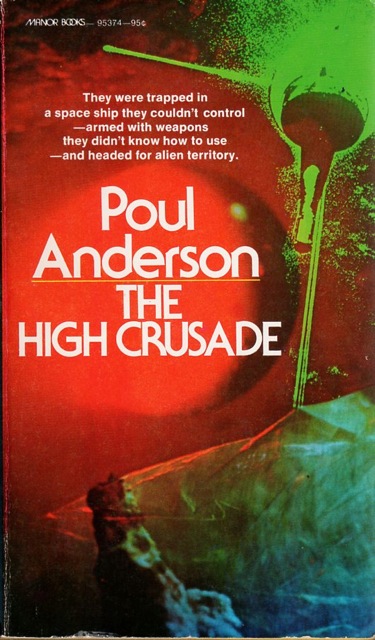

my readying to attack France, but I wasn’t interested in cheap anti-medieval stereotypes or scorn. That the book was titled The High Crusade only seemed another warning. Still, I went ahead and read the novel. I’d paid for it, after all, even if only a song.

my readying to attack France, but I wasn’t interested in cheap anti-medieval stereotypes or scorn. That the book was titled The High Crusade only seemed another warning. Still, I went ahead and read the novel. I’d paid for it, after all, even if only a song.

Congratulations to our 2015 Autumn Writing Challenge winner: Lady Arin. I’ll be contacting her privately to arrange her gift card from either Amazon or B&N.

Congratulations to our 2015 Autumn Writing Challenge winner: Lady Arin. I’ll be contacting her privately to arrange her gift card from either Amazon or B&N.

Letâs return to the mechanic for a moment. If itâs not apparent by now that the manâs mental bifurcation of reality into separate âsacredâ and âsecularâ realms is deeply mistaken, consider this: he, and those like him, pay the pastorâs salary. Without his âsecularâ job, without his revenue-generation, there can be no pastor, no church, no âsacredâ anything. He makes it possible.

Letâs return to the mechanic for a moment. If itâs not apparent by now that the manâs mental bifurcation of reality into separate âsacredâ and âsecularâ realms is deeply mistaken, consider this: he, and those like him, pay the pastorâs salary. Without his âsecularâ job, without his revenue-generation, there can be no pastor, no church, no âsacredâ anything. He makes it possible. Thereâs a pervasive notion out there that full-time evangelists deserve preeminent status in Christendom, and that they somehow know better than the rest of us how to make use of our various talents. But as C.S. Lewis writes in Mere Christianity:

Thereâs a pervasive notion out there that full-time evangelists deserve preeminent status in Christendom, and that they somehow know better than the rest of us how to make use of our various talents. But as C.S. Lewis writes in Mere Christianity:

This book was the most difficult and challenging project I had worked on, but what I learned from the experience went way beyond the writing craft.

This book was the most difficult and challenging project I had worked on, but what I learned from the experience went way beyond the writing craft.