The Doctor Doesn’t Believe in the DevilâShould We?

Some stories are special.

The ones that grab our attention and capture our imagination in startling ways and on deeper levels that sink into our core.

They leave us breathless, hearts pounding.

And sometimes, their underlying ideologies are more atrocious than dragon breath. Such as a two-parter in David Tennantâs first season as the Doctor.

What are we supposed to do when confronted by such discrepancies?

As Christians, how canâand shouldâwe filter the dogmas used in secular entertainment?

Note: contains spoilers for episodes 8 and 9 of Season 2.

When the Doctor Meets the Devil

In âThe Impossible Planet,â the Doctor and Rose find themselves stranded on, wellâŠthe title says it all. A planet that shouldnât really exist. Where a small Torchwood team is conducting a mining operation. Over the course of the episode, they discover the planet harbors a dark secret more terrifying than they could imagine.

Image via tardis.wikia.com

That leads to âThe Satan Pit,â where the pieces begin to fall into place. Turns out, the planet is also doubling as Satanâs prison. Cue many complications for the crew, the Doctor, and Rose as well as a launch into the explorations of religion as theyâre forced to face the reality of the Devilâs existence.

Now, this is BBC weâre talking about. Not exactly known for being a bastion of truth. As such, it comes as no surprise that the underlying philosophy was as strong as a punctured piece of tinfoil.

And the main culprit? Guess who…

To Believe or Not to Believe

As the characters are confronted with more evidence and more encounters that become unmistakable, they find their beliefs shaken. The Doctor remains unconvinced, which leads to this exchange with one of the crewmembers:

The Doctor: You get representations of the horned Beast right across the universe in myths and legends of a million worlds. Earth, Draconia, Vel Consadine, Daemos… The Kaled god of war, the same image, over and over again. Maybe, that idea came from somewhere. Bleeding through, a thought of every sentient mind…

Ida Scott: Originating from here?

The Doctor: Could be.

Ida Scott: But if this is the original, does that make it real? Does that make it the actual Devil?

The Doctor: Well, if that’s what you want to believe. Maybe that’s what the Devil is, in the end. An idea.

He also gives a reason for his distrust:

If that thing had said it was from *beyond* the universe, I’d have believed it. But before? Impossible.

Amusing side note…this image’s size is 666 x 500. #coincidence?

Ironically, his reasoning is as airtight as a spacesuit with a leak. Why? Because at the beginning of episode 9, when he and Rose discover the planet is orbiting a black hole, he says, âBut thatâs impossible.â Yet heâs staring at proof that heâs wrong.

Given that recent undermining of his belief, his doubt of the Beast’s claim loses potency.

Eventually, after coming face-to-face with the Beast, the Doctor concedes its physical existence. But in his worldview, he canât admit to confronting the actual Devil, something more than an idea.

The Doctor confronts the Devil.

Image via tardis.wikia.com

What, then, does the Doctor believe in? He tells us in this passionate, stirring, hopelessly askew declaration (referring to Rose at the end):

Well, I’ve seen a lot of this universe. I’ve seen fake gods and bad gods and demi-gods and would-be gods. I’ve had the whole pantheon. But if I believe in one thing… just one thing… I believe in her!

Sounds great but really, Doctor? Is that the best you can do?

Which begs the question, how do we reconcile such a fantastic story with such a flawed message?

Separating Story from Worldview

The storytelling in the episodes is superb. Relentless pacing, unique setting, high stakes, impossible situations, mysteries, betrayal, sacrifice, plot twists. Everything you could want from a story.

Except for a strong theme.

What makes this example fascinating is the juxtaposition of storytelling prowess and Truth-based ineptitude.

Itâs both inspiring and depressing.

As Christians, whatâs the best way to react when faced with a situation like this?

I donât think you can apply a cookie-cutter approach, where one way is exactly right and everything else falls outside the lines. And I know some people may object to watching or reading stories that stray so far from the true north of Truth. Nothing wrong with that. But for those who enjoy secular entertainment, how do we approach the question?

At the core, it boils down to expectations. We donât expect Doctor Who to present us with a Christian view of the world. Neither do we expect to derive the foundational pillars of what we believe and why we believe it from the show either. Or any other mainstream entertainment.

Weâll take that from the Bible, thank you.

Can we learn from these stories? Absolutely.

Should we come to them with care? Always.

This frees us to appreciate secular stories for the benefits they do have. However, that leaves the responsibility in our court (or TARDIS). Rather than being passive bystanders, we should constantly filter what we watch and read through the lens of our worldview. One informed by the Truth and able to discern the falsehoods, no matter how brazen or subtle.

When we do that, we can enjoy well-made stories, though they may stray far from the truth. Because even if the Doctor sees the Devil as nothing more than an idea, heâs not always right.

What are some ways Christians should approach stories that blatantly fly in the face of Truth? How have you personally handled such issues?

Here at Spec Faith we have, from time to time, had a writer give an apologetic for the horror genre of fiction. I’m thinking of articles by Brian Godowa (a series existing of

Here at Spec Faith we have, from time to time, had a writer give an apologetic for the horror genre of fiction. I’m thinking of articles by Brian Godowa (a series existing of  Stories in the horror genre replace what much of the contemporary song writers are ignoring.

Stories in the horror genre replace what much of the contemporary song writers are ignoring. I don’t think so. Rather, I believe this sort of ho-hum attitude to the horrors of life—either on the spiritual plain or the physical—is a symptom of what Scripture refers to as a hard heart. We are no longer moved by that which should trouble us, by that which should caution us. We simply want the emotional rush, at all costs, and no longer bother to deal with the psychological factors, let alone the spiritual repercussions.

I don’t think so. Rather, I believe this sort of ho-hum attitude to the horrors of life—either on the spiritual plain or the physical—is a symptom of what Scripture refers to as a hard heart. We are no longer moved by that which should trouble us, by that which should caution us. We simply want the emotional rush, at all costs, and no longer bother to deal with the psychological factors, let alone the spiritual repercussions.

In addition, without a reality-sin issue at the heart of fantasy, few readers can assign the problem to Others. (Oh, sure, those Other people—the ones addicted to Turkish Delightâthey really need to read this book, but that’s not me!) Thus fantasy depicts evil in a universal way, even as it personalizes the protagonist’s struggle, thus allowing readers to identify with the character, though their own struggles may be with vastly different issues.

In addition, without a reality-sin issue at the heart of fantasy, few readers can assign the problem to Others. (Oh, sure, those Other people—the ones addicted to Turkish Delightâthey really need to read this book, but that’s not me!) Thus fantasy depicts evil in a universal way, even as it personalizes the protagonist’s struggle, thus allowing readers to identify with the character, though their own struggles may be with vastly different issues.

We live in a broken world.

We live in a broken world.

Why do you think stories should or shouldnât shy away from showing evil?

Why do you think stories should or shouldnât shy away from showing evil?

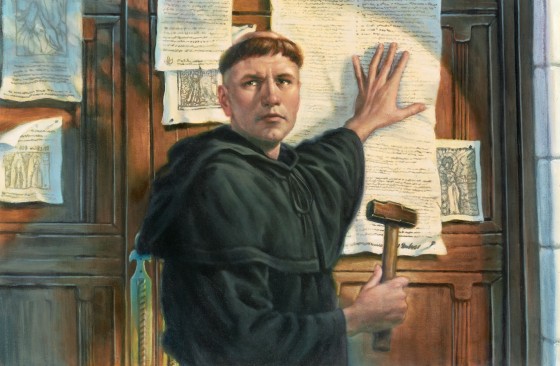

October! As we dive into the heart of autumn, many turn their thoughts toward the spooky. I’ve seen ads for scary movies, horror-ish TV programs, and the requisite decorations and costumes that accompany Halloween. I thought perhaps it was time to revisit some thoughts on the subject of evil. Hence, this re-post of an article that first appeared here five years ago. It’s about a timeless subject explored by one of the timeless pieces of speculative fiction.

October! As we dive into the heart of autumn, many turn their thoughts toward the spooky. I’ve seen ads for scary movies, horror-ish TV programs, and the requisite decorations and costumes that accompany Halloween. I thought perhaps it was time to revisit some thoughts on the subject of evil. Hence, this re-post of an article that first appeared here five years ago. It’s about a timeless subject explored by one of the timeless pieces of speculative fiction.