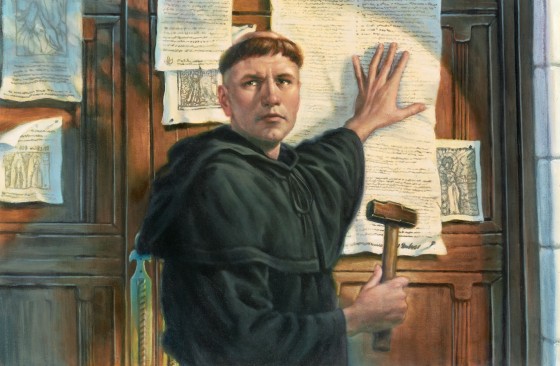

95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation, part 2

This month, Christians worldwide celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Reformation.

“Reformation,” in this context, doesn’t mean simply overthrowing old traditions for the sake of novelty or progress. It means a return to a biblical view of salvation and church practice. Martin Luther and other Reformers believed (I think rightly) that the Church of that time had forgotten or rejected these biblical views, and taught dangerous doctrines.

On a smaller scale, Christians should always compare “the way things have always been” with Scripture. Not to their own annoyance with old things. But to Scripture.

In that spirit, and naturally 95-theses-style, I’m evaluating Christian-made fiction:

- The purpose of Christian-made stories,

- What’s wrong with Christian-made stories,

- What’s right with Christian-made stories,

- How Christian readers can reform these stories in the future.

Last week we explored the purpose of Christian-made stories. Now let’s explore what’s wrong with them.

Part 2: What’s wrong with Christian-made stories

- Christian-made fiction’s worst errors come from shallow or false beliefs about our faith.

- Some Christians think our bodies are eternally disposable; only souls will last forever.

- Similarly, many think human creativity is eternally disposable; only truth lasts forever.

- Without robust, biblical views of art, Christians will view human stories like they view their bodies: disposable “containers” whose value is only in carrying the “soul” of truth.

- This is the worst false belief plaguing Christian fiction. It leads to poorly made stories.

- Yes, non-Christian culture also has many badly made things. However, this is no excuse for treating uncreative Christian-made stories as if they are truly creative works of art.

- Christian fiction may include poor characters, predictable plots, and limited style.

- Christian fiction may refuse to show the world truthfully. Its censored ideas or words often show a “clean” world, in which non-Christians are simplistically nice people (who just need to realize that God truly does love them) or else simplistically villainous.

- These stories are not merely bad art because they censor ideas or words. They are even more dangerous because they imply evil is weak—and make the Gospel look weaker.1

- Even Christian stories that want to value “truth” over creativity don’t handle truth well.

- Some novels may ignore Gospel themes, preferring moralistic or prosperity “gospels.”

- Moralistic “gospel” stories replace exaltation of God’s grace with exaltation of manmade laws, which can include religious rules, cultural Christianity, or patriotism.

- Prosperity “gospel” stories imply that conversion to Jesus will always improve your life in some way, such as by giving you good feelings, restored relationships, or true love.

- In fact, too many Christian novels seem to focus on the plight of nonbeliever characters.2

- In the past, too many Christian novels focused on prophecy or “end times” speculations.

- Today, too many Christian “nonfiction” books are merely bad fiction in disguise. These include, but aren’t limited to, “heaven tourism” books3 and more prophecy speculations.

- Our fantastic faith with God, miracles, and a fantastic eternal future has somehow led to a less-fantasy-minded readership that wants to escape the miraculous/fantastical.

- Some Christians have tried to publish more fantasy. But readers do not care for it.4

- Most Christian readers want their fiction to affirm uniquely western Christian culture, rather than exploring the Gospel in the lives of people from diverse or fantastic worlds.

- This leads to fiction that emphasizes a particular faith “fashion” over transcendent faith.

- Many Christian readers apparently believe the myth that finding true romantic love is the highest paradise we can conceive, and this directs their reading preferences.

- This leads to less-fantastic trendy genres such as Amish romance or historical romance.5

- Some Christians may believe reading fiction is a waste of time, which is best spent doing more spiritual things such as prayer, Bible reading, or supporting missions efforts.

- Some of these Christians may still like fiction, but feel guilty instead of robust about it.

- Other problems plaguing Christian fiction include, but are not limited to:

- readers who value novels from “the bench of bishops,” that is, trusted Christian nonfiction-genre authors, pastors, or celebrities, rather than from trained “Christian novelists and dramatists”6

- readers who ignore or reject truly excellent Christian-made fiction, partly because it’s not as popular in the world as, say, Marvel movies or prestige television drama

- readers who believe Christians should not have their own separately labeled fiction at all (unlike every other interest group that does often label its people’s fiction)

What other problems have you found with Christian-made fiction, including fantasy?

And more importantly, how would you personally try to help improve Christian fiction?

Continued in part 3: What’s right with Christian-made stories?

- Explore more about this problem in A Call For Deeply Real Christian Fiction. ↩

- Explore more about the problem of simplistic nonbeliever characters at Fiction Christians From Another Planet! IV: Terror Of The Megachurchians. ↩

- Explore more about “heaven tourism” books, and the problematic trends behind them, at Heaven Malarkey: Lifeway, Tyndale and The State Of Christian Publishing. ↩

- Explore more at Why Isn’t There More Christian Fantasy? ↩

- Explore more at Why Does Christian Romance Outsell Christian Fantasy? ↩

- These quoted phrases, “bench of bishops” and “Christian novelists and dramatists” both come from C.S. Lewis in Mere Christianity. He referred to the problem of people expecting Christian clergy to do all the heavy lifting in culture: “The clergy are those particular people within the whole Church who have been specially trained and set aside to look after what concerns us as creatures who are going to live forever: and we are asking them to do a quite different job for which they have not been trained. The job is really on us, on the laymen. The application of Christian principles, say, to trade unionism and education, must come from Christian trade unionists and Christian schoolmasters; just as Christian literature comes from Christian novelists and dramatists–not from the bench of bishops getting together and trying to write plays and novels in their spare time.” ↩