Are We Actually More Like the Villain Than the Hero?

Image via marvelcinematicuniverse.wikia.com

Heroes get all the attention.

They’re the ones plastered on movie posters and book covers. They’re the ones with book titles using their name and storylines told from their point of view. They can have their cake (or Lembas) and eat it, too.

Which means the story’s second-most-important character, the villain, gets left in obscurity.

At times, we get glimpses into the villain’s world, life, and perspectives. But when do villains receive the attention heroes enjoy?

Rarely.

There are plenty of reasons for this:

- Heroes are, well, the heroes.

- The heroes fight for goodness and truth and life, while the villains often embody the opposite.

- Villains are seen as nothing more than the evil mastermind, the one to wreak havoc, display awful morals, and present a compelling challenge for the hero to face.

Generally speaking, heroes get positive attention, while a negative attitude is reserved for villains. Makes sense, given their titles, but should it be this way?

More importantly, do we overlook something when thinking about stories? Namely, which archetype falls closer to us, the readers, on the heroic-to-villainous spectrum?

Housekeeping note: In the context of this article, “villain” doesn’t always refer to the main evil character set against the hero. It can be any antagonist. Example: The White Witch may be considered the villain of the story, but for my purposes, Edmund falls into that category as well.

Are We the Hero or the Villain?

Early on in literature, the line between hero and villain was more distinct, a clear brush stroke dividing white and black on the story’s canvas. Modern stories have taken a different approach. Blending the two, we’re left with lots of muddled gray areas.

The happy home of antiheroes, flawed characters who are still on the good side, and villains with more complex characteristics that run deeper than “out to rule or destroy the world.”

Nothing wrong with that, but it muddies the water and begs the question: where do readers fit? After all, a strong narrative will include relatable characters. Characters who remind us of ourselves—in good ways and bad ways.

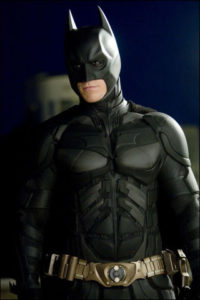

Image via batman.wikia.com

Who are those characters?

Heroes, duh.

Hold on. Not so fast.

It’s true we all view ourselves as the hero of our own story. Guess what?

So do villains.

Yep, those rogues, tyrants, and killers all see themselves as the hero. The motivation and thought process behind that depends on the character, but a fleshed-out villain isn’t there just to hurl bombs at the hero. They seek an outcome. One that’s right, even if only according to their twisted worldview.

Image via lotr.wikia.com

That leaves us in a conundrum. Because if we’re honest, deep down, we see startling similarities between ourselves and villains. I’m not saying we’re psychopaths like the Joker or tyrant wannabes like Sauron.

But who hasn’t been greedy, selfish, unforgiving, angry, vengeful? Typical villain fare. Who hasn’t felt like two-faced Harvey Dent or shown flashes of Gollum? It has a root cause, a nasty disease that afflicts us all.

Also known as sin.

A Different Kind of Hero

Last week in 95 Theses for Christian Fiction Reformation, part 1, E. Stephen Burnett brought out some fascinating truths:

-

The greatest stories come the closest to reflecting truth, beauty, and goodness in our world.

-

The greatest stories also come the closest to reflecting the lies, ugliness, and evil in our world.

A knight in not-so-shining-armor.

Rich stories carry truth, beauty and goodness. Yet they don’t avoid the lies, ugliness, and evil that infect everything.

In order to connect with the characters on a meaningful level, we need to relate to them. We need to have them look in the mirror and see our reflections. Going back to the prevalence of gray areas, this is why antiheroes became popular. It’s hard to relate to a knight in dazzling armor whose virtue outshines the sun.

Because that’s not who we are.

If we have any armor at all, it’s probably tarnished. And our virtue has as many frayed threads as Sam and Frodo’s clothes by the time they reached Mount Doom.

It’s not a stretch, then, to say we land closer to the villain’s camp than the hero’s. We wish to be like the Avengers, saving the world and using our power for good. That’s not wrong. However, people don’t usually wish for something they already have.

In fact, only one real life “Hero” has ever measured up to the knight-in-shining-armor standard.

A Different Kind of Story

Stephen went on to say:

-

Only the gospel of Jesus Christ shows all of these elements most clearly.

-

The gospel of Jesus Christ, as Self-revealed by God in the Bible, is the greatest Story of all time.

-

Jesus “wrote” the gospel, with Himself as the Hero, into reality, so He is the greatest Storyteller.

Part of the reason we love reading about heroic characters is because we know we’re not heroes. We love to strive and imagine and dream about being as principled as Captain America or loyal as Samwise. But we fall pathetically short and look to heroes to fill the gap.

Sure, people can do good—I’m not denying that. So can villains. And in the greatest Story, we’re just that. Enemies of the hero. Villains set against Him.

Major plot twist: it turns out we aren’t actually the heroes of our own story. But for the saving grace of God, our character arc would be much different. Left to ourselves, we’re on the wrong side.

Image via narnia.wikia.com

That doesn’t leave us stranded without hope. We may start out like Darth Vader, drawn to the Dark Side. Yet God doesn’t leave us there, and our story turns into a redemptive arc, à la Edmund and Eustace.

So yes, there’s a sense in which we can identify with heroes. But those underappreciated villains? They’re more like us.

Which is why the hope and beauty of redemption gleam like the burning beams of sunrise into a dark and villainous world.

Do you think we’re more like heroes or villains? Why do you think we more readily identify with heroes?