Donât Let Halloween Mock the Resurrection

Yes, itâs okay for Christians to celebrate Halloween.

These days the occasion has mostly become Fan-o-ween anyway. Kids and grown-ups alike can feast and celebrate stories, scary ones and otherwise. Some people may be tempted to indulge in occult activities, and yet most Christians really arenât. Being âoffendedâ or fearful is not the same as actual temptation to you personally.

But.

Even after Iâve spent many years of spiritual maturing, Gospel-embracing, and legalism-hatred, Halloween still makes me nervous.

I donât mean the candy-and-costumes part. I donât even mean the emphasis on scary story tropes and creatures. After all, horror is a story genre that can prove redemptive. This is especially true when authors use horror to truly illustrate the horror of manâs condition apart from Christâor the horror of evil spiritual realities apart from Christ.

Instead Iâm thinking of two ways Halloween bothers me. These two particular methods are very different. But people (or the Devil, or somebody) have found a way to do both at once.

1. People wrongly make light of the darkness.

Christians are set free from bondage to sin and Satan. We can celebrate this freedom.1 In one sense, even as we guard against Satan and his lies, we can even laugh at the Devilâs attempts to scare us:

Christians are set free from bondage to sin and Satan. We can celebrate this freedom.1 In one sense, even as we guard against Satan and his lies, we can even laugh at the Devilâs attempts to scare us:

The gospel reveals that much of the fear that Satan excited in men prior to the advent of Christ resulted merely from the exaggerated shadows that he cast in the darkness. Now that light has come the shadows are removed and Satan is reduced to a far less terrifying stature. We can begin to laugh at the shapes that we once saw in the shadows.2

Non-Christians canât do this because they donât have the Christianâs freedom.

But with much of todayâs Halloween celebration, they try anyway. They make decorations and movies based on terrifying creatures: zombies, spiders, wraiths, and the gravestones and skeletons. (Always the gravestones and skeletonsâas if the very concept of dying, rotting away, and leaving nothing behind but a grinning set of remains isnât terrible.)

People try to laugh at death. They try to make light of the darkness.

However, non-Christians have no cause to laugh. For anyone outside Christ, death and darkness are the greatest true fears. Without Him, weâll end up nothing but headstones and skeletons at best. Thatâs not hilarious. Itâs seriously terrifying. Mocking these truths is just as absurd and self-destroying as mocking the train speeding at you while you are tied to the tracks.

Itâs not the laughter of a warrior whoâs truly victorious over darkness and death.

Itâs a laughter more like the Joker right before the amusement park explodes.

2. People exchange real light for ghoulish darkness.

Even as Halloween celebrations and decorations make light of serious terrors, these things can also cast glorious, beautiful truths as if they are horrific evils.

So Grandpa won’t come back as a glorified saint, but as a ghoul.

Picture the same decorative emphases on zombies, tombstones, skeletons, and ghosts. All of these are symbols of one Halloween idea: âthe dead come back to life.â

In every instance, weâre led to concludeânot with thoughts, but with assumptions and feelingsâthat coming back from death is a terrible thing. If you do, youâll be a skeleton. A zombie. You won’t be alive, but âundead.â

Taken by itself, this is a very real terror. If by some mystical or scientific means, people did return from the dead, that would be terrifying. Even worse, imagine if the body had already decomposed or if you were reduced to an animated skeleton or shambling corpse.

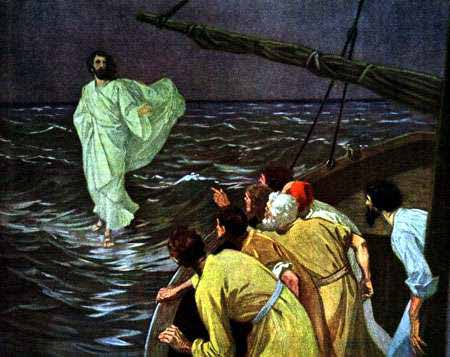

Now look what happens at the holiday opposite from Halloween: Easter, or Resurrection Sunday. Halloween occurs at fall, just before the world enters a season of decay leading to death. But on Easter Sunday at spring, heralding the season of new life, we celebrate the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. He did not merely become âundead.â He defeated death itself and was raised to life, the selfsame Person he was before he surrendered his life.

Yet in response to this truth, non-Christians mock the idea of Jesusâs resurrection. What do they say about him?

They canât help but use Halloween imagery. They say, âha ha, zombie Jesus.â

They assume the notion theyâve absorbed from horror tropes: that if you come back from the dead, it canât be anything good. Itâs terrible. Itâs dark, evil, perverted.

All at once, the beautiful truth of the resurrection becomes a terrible fright.

The glorious promise Jesus and the apostles proclaimed, of real and permanent miraculous return from death to live forever in His kingdom, becomes a freak of magic or science.

Saintsâ new Spirit-powered bodies 3 pulsing with divine light are mutated into corpses of rotting flesh.

Even the initialed, subtle promise of resurrection emblazoned on tombstones gets turned into a scary set of letters. Instead of âRest in peace,â we get âRIP,â like the verb rip. Three of the most light-bringing words in the language are exchanged for a threat of darkness.

What then of Halloween?

We didnât distribute candy to trick-or-treaters this year. That was a fluke; I forgot to buy candy. We wonât revert to a posture of legalism or fear against any holiday. Unlike our non-Christian friends, we can laugh at the darknessâand also help redeem the dark stuff.

But.

In years to come, I may push back against peopleâs ingrained habits to try making light of darkness. I may question whether we exchange real lightâthe hope of resurrectionâfor dark perversions of the concept, such as zombies and animate skeletons.

If anything, we simply need to ask these questions. For any holiday we celebrate, we should understand why weâre decorating and feasting and enjoying any other tradition.

So for Halloween, we might reasonably ask, âCan I put in my yard this plastic tombstone with âRIPâ ironically, or is there some part of me that suspects resurrection would be terrible?â Or, âAm I making light of death and horror because Iâm strong in Christ and know that death has no ultimate power over me? Or am I trying to laugh away the real ghouls of evil that I suspect are still lurking out there in the world, ready to attack me any second?â

Don’t feast and celebrate at Halloween with any forced laughter at undefeated death. And don’t let suspicion of beautiful, miraculous Resurrection creep in either. Instead, recall the holiday’s roots: not to celebrate death, but celebrate the saintsâsaints who won’t return as undead ghouls, but as risen, glorified family and friends.

- This also means weâre bondservants to Jesus (1 Corinthians 7:22). He did not set us free for âfreedomâsâ sake. He loves us too much for that. Instead He sets us free for His sake, so that in living in service to Him we get the best pleasure in existence. ↩

- Of Boggarts, Alistair Adversaria, July 24, 2007. Quoted in âCasting The âRiddikulusâ Spell On Halloween,â E. Stephen Burnett at Speculative Faith, Oct. 27, 2010. ↩

- See 1 Corinthians 15. In verses 44-45, the apostle Paul says our new bodies will be âspiritual,â unlike our old bodies that were ânatural.â Paul is not saying our new bodies will be ghost-like or non-material. He means that our new bodies will be empowered by the Holy Spirit. ↩

October 31—what holiday is the first that comes to your mind?

October 31—what holiday is the first that comes to your mind?

AYLA THINKS SHEâS JUST a comic-book geek with photophobia living in boring Colorado Springs until the day a space fold forms in her living room. When her father drags Ayla through to the other side, she discovers an alien world. Her birthplace. Karanik.

AYLA THINKS SHEâS JUST a comic-book geek with photophobia living in boring Colorado Springs until the day a space fold forms in her living room. When her father drags Ayla through to the other side, she discovers an alien world. Her birthplace. Karanik. As a child raised in the Southwest United States on the border of one of the largest oil fields in the country, S.J. Abraham was a lonely nerd. With no interest in rodeo or baseball, he spent his time reading. His heroes were fictional characters and great novelists. It wasnât long before he started scratching out his own stories.

As a child raised in the Southwest United States on the border of one of the largest oil fields in the country, S.J. Abraham was a lonely nerd. With no interest in rodeo or baseball, he spent his time reading. His heroes were fictional characters and great novelists. It wasnât long before he started scratching out his own stories.

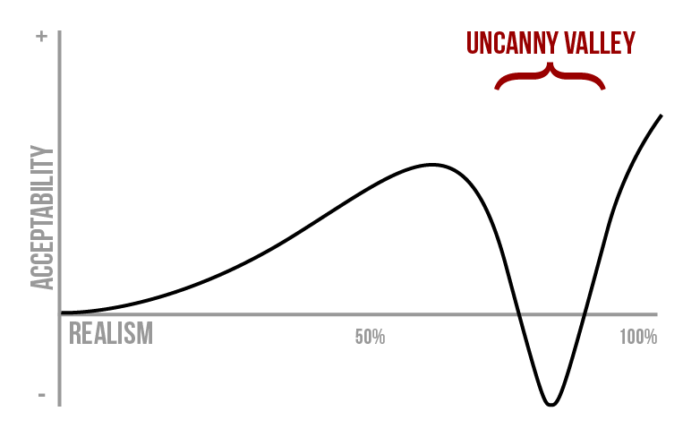

It highlights, for example, the psychological quirk that humans are unnerved by things that ought to be human and donât quite make it, both pretend-humans and ex-humans.

It highlights, for example, the psychological quirk that humans are unnerved by things that ought to be human and donât quite make it, both pretend-humans and ex-humans.

Like movies, video games contain an inherently visual aspect. Fortunately, no real people are involved. But that doesnât lessen the reality of an industry once again saturated by tantalizing visuals.

Like movies, video games contain an inherently visual aspect. Fortunately, no real people are involved. But that doesnât lessen the reality of an industry once again saturated by tantalizing visuals. Books are the least likely culprit, since they donât contain any pictures. But that doesnât mean theyâre squeaky clean. Far from it. Plenty of books contain sexual content, abusive characters and victims, the list goes on.

Books are the least likely culprit, since they donât contain any pictures. But that doesnât mean theyâre squeaky clean. Far from it. Plenty of books contain sexual content, abusive characters and victims, the list goes on.

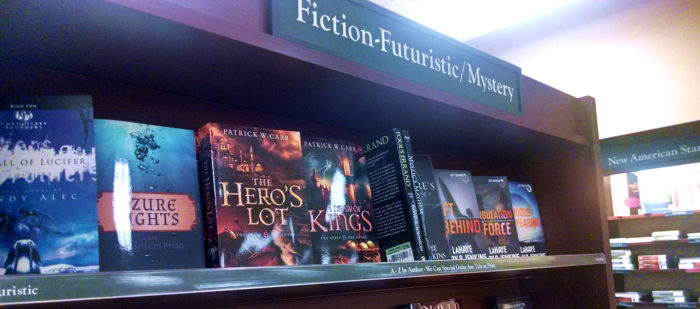

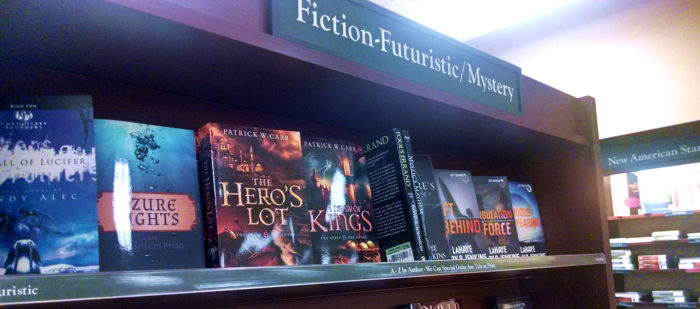

Part 3: What’s right with Christian-made stories

Part 3: What’s right with Christian-made stories Christian novels span a variety of common genresâincluding some fantasy and science fictionâand have created new genres, such as Amish romance and end-times thrillers.

Christian novels span a variety of common genresâincluding some fantasy and science fictionâand have created new genres, such as Amish romance and end-times thrillers.