This post was inspired by what Mark Carver wrote yesterday discussing alternate reality scenarios as seen in one piece of speculative fiction. His piece inspired me to break out an old article from my personal blog which discussed alternate reality scenarios and adapt it for Speculative Faith. In short I don’t agree with Mark that Divine Sovereignty requires only one reality. While it’s possible (maybe even probable) there’s only one, I don’t think I can be sure without more information. This post will explain how Quantum Mechanics leads some people to believe there are multiple universes, alternate realities, via the Many Worlds Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics and will give some ideas on specifically Christian twists a storyteller could give a MWI view of reality.

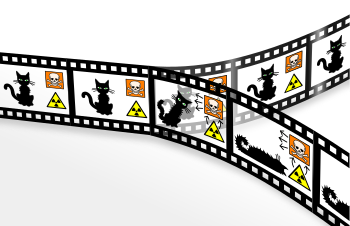

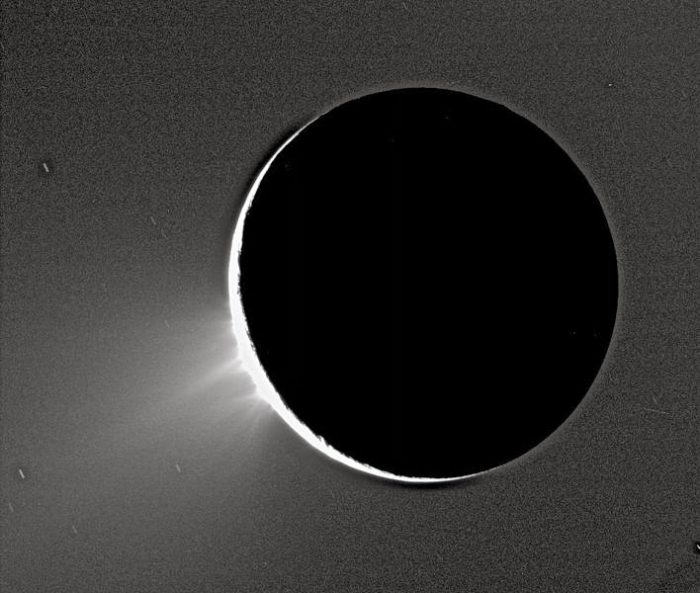

The division of universes showing a cat both alive and dead at the same time until someone makes a definite measurement, i.e. Schrodinger’s cat. In the Many Worlds Interpretation, the cat lives in one universe and dies in another. Source: Wikipedia Commons

I first of all have felt compelled to explain what MWI actually is in my own words. For readers who feel they understand MWI well, feel free to skip down 7 paragraphs to where I will begin talking about what MWI implies and how that relates to story ideas with a sentence in bold print.Â

In short, MWI sees that all possible alternate histories and futures are real. A way to tie that back into the specific language of physics would be to affirm that this interpretation “asserts the objective reality of the universal wavefunction and denies the actuality of the wavefunction collapse.”

For those readers who may not understand the phrase I just used above (I pulled it off the Wikipedia article I linked to MWI, by the way), I’m going to put into lay terms what I just quoted, using an electron as my example. According to quantum mechanics, the exact position and motion of an electron cannot be known. Not fully. To keep this as brief as possible, that implies the position of an electron (and other quanta) can only be estimated based on probability. The electron can in fact be nearly anywhere, but the chances of it being on the other side of the universe when it just left an atom here on Earth is very close to zero. Note what I just said–the chances are “very close” to zero. But they are not zero. According to quantum mechanics there are very low probabilities (yes very, very low) that an electron that was on Earth just a nanosecond ago, is now a nanosecond later in the Andromeda galaxy somewhere. Yes, this definitely seems to contradict everything you have heard about the speed of light, that nothing can go faster than the speed of light in a vacuum, which would be about 300,000 kilometers per second and which would require about 2.5 million years to get to Andromeda. (In more ways than one, the physics of quantum mechanics does not agree with the physics of relativity very well.) However, the chances are much, much greater that the electron is somewhere not far from its last position.

So the situation I just described, concerning the position of any quantum such as our example electron being unknown, means in modern physics that the possible locations of the electron are calculated based on where it might be using probability math, producing something called a “wavefunction.” (Wavefunctions can be combined to provide for all possible locations of an electron. All such possible combinations of wavefunctions is what the term “universal wavefunction” is driving at.)

For reasons I am not going to explain here in detail that have to do with wave interference, it appears that our electron weirdly actually is in a wide variety of places at the same time when it’s described as a wavefunction. So it isn’t just that an electron (or other quanta) is a particle in one place that’s hard to find–it’s acting as if it’s a different kind of thing, a wave, that is in fact occupying all the possible places it could be at once. But when you measure where the individual electron happens to be at any given moment within the wavefunction, it “collapses,” which means that instead of being in many places, the act of measuring the electron forces it to actually be in just one place at a time, so all the probable locations become one-and-only-one observed location. Note that doesn’t seem to be the same as not knowing where the electron is and finding it. The “finding it” appears to change its nature and causes it to behave in a completely different way that it would if it were unmeasured. As the linked article explains in detail, experiments show that if you measure the position of an electron it will fire through double slits like a series of bullets–but if you don’t measure it, it will create interference patterns like waves of water do.

The Many Worlds Interpretation says our hypothetical electron seems to be in many places because there are a wide range of universes stacked on top of each other in which the electron actually is a point particle located in each possible place it could be. Somehow these alternate universes interfere with one another on the quantum level to create wave characteristics and are also seen in the mathematical feature of the wavefunction that seems to give probable simultaneous locations. When I make a measurement about the specific location of an electron, instead of the wavefunction collapsing so that all the possible locations boil down to only one location, the MWI interpretation says that the electron continues to be in all the separate places it could be–there is no collapse. But the electron loses contact with other possible universes where it could be at that moment, in effect making us select just one of the possible universes f0r its location. Meaning we just happen to be living in only one of the possible outcomes for that electron. All the other possibilities continue to exist in other universes which become separated from us.

MWI sees the number of universes as not only for all practical purposes infinite, it sees that with each branching of quanta, with each apparent wavefront collapse, with each decision if we want to think of it that way, the number of universes increases. And since every possible action (even brain function) can be accounted for by quanta either going one way or the other, there would be a universe in which every possible decision that could be made at the tiniest scale was in fact made. If MWI is true.

So why did I bother to explain the meaning of the Many Worlds Interpretation? To make a few things clear about it:

- It’s just one way of interpreting physics. It is in no way actually known to be true–there are other possible interpretations of quantum mechanics, including what I already stated about each quanta actually assuming the form of a wave when unmeasured, actually not even having a definite location unless measured (this view is called the Copenhagen Interpretation of quantum mechanics). So if anybody tells you science knows MWI is true or alternate universes exist for certain, they are wrong.

-

It’s a view of the universe based on science. So some very smart science-nerdy people buy into MWI wholeheartedly and think this is how the universe really works (I tend to disagree with them–not that I really can be sure–but that doesn’t matter here).

-

It undergirds the alternate reality sort of story which has become very popular in science fiction.

-

I think we can use this as a launching point to discuss a different kind of alternate reality story, one that presumes God is real and the Bible is His message.

Multiple Earths

So for the sake of hypothetical speculation, let’s say the MWI interpretation of quantum mechanics is actually true. How would that relate to the God of the Bible? Would it make God no longer sovereign of the universe?

Well, we don’t normally think of God as losing sovereignty because human choice exists. Even extreme Calvinists usually believe human beings are capable of making some decisions, even if they don’t believe a person can chose to accept God’s grace in salvation without God willing it.

If we’re able to accept choice by human beings without God losing sovereignty, why would it be so hard to imagine that God could allow the universe itself to make choices, to even split and divide along those choices? I believe a Biblical view of God is compatible with imagining God allowing multiple choices to exist simultaneously, multiple realities, and being the sovereign ruler of each one of them.

God himself would be immune to quantum fluctuations because he’d be their Creator and not the other way around. But the creation could be subject to multiple versions, some versions starting out differently even before what we think of as the heavens and Earth existing as we know them.

But if we see God as sovereign and the Bible we have as reflecting God’s intent, then all possible universes generated by the “Quantum Mechanics God of Alternate Realities” would begin with the same original creation, but then would begin to diverge after that. Which would affect all sorts of things in the world, but would also affect the Bible itself, because much of what the Bible records is what human beings do and how God interacts with them.

So in this view of God (in his sovereignty allowing for different versions of reality), there would be an alternate universe where Adam and Eve never sinned and the human race lives in a global Eden on Planet Earth. There would be a Moses who did not strike the rock when God told him to speak to it, who would enter the Promised Land instead of dying outside it. There would be an ancient Israel where the kings never strayed from righteousness, which was never conquered by the Babylonians. And another Israel in which the Jewish leaders under Roman domination would have wholeheartedly embraced Jesus. Etc.

This imaginary story conception doesn’t make God inconsistent with how we normally think of him. Human beings would have freedom to act and would in fact make all the possible choices they could have made. God would react to them as they responded to the choices he gave them–but God is capable of willing all the alternate versions just as much as he is able to create the one-and-only-one universe we seem (seem) to be living in.

Note that this is a non-deterministic look at God. God can’t have predetermined every single thing for this to work as a story. Or at least, if he did predetermine everything, he would need to have done so a horde of separate times, him allowing (well, actually, sovereignly ordaining) each choice a person could make to be performed throughout the universes. So there would be a plethora of universes all wrapped around individual human moral decisions, but since these changes would be serving God’s purposes and wouldn’t actually be a function of randomness, it would seem that while there could be a very great number of alternative universes, that number would not be infinite.

That’s especially true if God made human moral choice the source of the division of universes and not the rattling of tiny quanta–which would be one of the key differences between this sort of story framed by a Christian worldview and the typical science fiction alternate reality tale.

Since God’s character would remain the same in this Christian version of MWI, there would still be a sacrifice for sin, if sin in fact were to be introduced into the given world (it would seem sin would be a part of all possible worlds except only for one, the one in which Adam and Eve obeyed perfectly). But Christ would have to die in separate circumstances for each reality, each separate universe having its own version of the Savior for the universe at that point. Christ dying once for sins, as the New Testament says he did, would only apply to once for any given universe.

So, what if for each possible choice presented to human beings by God in Biblical times, a version of the Bible existed which covered the people choices made? A Bible version of obedience and disobedience, for each possible choice? Though all of them beginning with a creation, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, and all of them ending with the human race reconciled to God for eternity in the new heavens and new earth.

So there would be a plethora of possible Bibles. Not an infinite number, because the moral choices God mandated human beings make in Scripture are not infinite in number. Say there were 10,000 different Bibles across the universes. Or 7,000–that’s more of a Biblical figure. đ (though if we were to count small changes, 7 million might be more like it)

Why shouldn’t a Christian author of science fiction feature a story where the character of God is consistent but the people who responded to God did radically different things? So as people somehow cross into an alternate reality, as so often happens in stories like this, they would find all possible realities contain a Bible and Christianity (or something essentially like it), but the Bibles were not in fact the same in each alternate world? And the very worlds people lived in were different as well, based on both on choices all people make in their lives, but also based on differing Biblical influences?

I see no problem for story purposes extending this moral decision-making past Biblical times. So there might be 7,000 versions of the Bible, but each individual Bible would have separate alternate universes branching off from it, separate universes in which that particular original text was used.

So the universe that produced our Bible, as we have it, would have separated further after Scripture was written. So it would represent perhaps tens of millions of alternate realities, each reality based on moral choices made in relation to God post the writing of the Bible we know.

Likewise there would be tens of millions of alternate realities linked to other alternate-reality Bibles. Variations in Scripture and translations could become a key means of figuring out which universe you were in–or at least in which set of universes you had entered.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if also all versions of the Bible, no matter what they are, all had word for word the same first and last chapters, even if everything else in them changed? Which would mean that God would bring all the different quantum universes to the same eternal state, just as all of them came from the same initial creation.

I have more thoughts on versions of alternate realities compatible with a Christian worldview that I’ve already shared on my own blog. Perhaps in the future I will bring them up here.

In the meantime, do you agree or disagree with me that alternate realities are fair game for Christian writers of speculative fiction? Do you think God really could have allowed multiple universes–or do you think I’m dead wrong about that? And what stories do you know of by Christian authors that have looked at alternate-reality type scenarios?

services. Youâll want to be around then.) I had been aware of them for years, like everyone else on the planet, and I had even been induced to watch a few. They were very close to me, the people who persuaded me to try Marvel, and so they didnât mind that I brought my laptop to the experience. It proved an excellent diversion.

services. Youâll want to be around then.) I had been aware of them for years, like everyone else on the planet, and I had even been induced to watch a few. They were very close to me, the people who persuaded me to try Marvel, and so they didnât mind that I brought my laptop to the experience. It proved an excellent diversion.

âIâve Always Loved the Magic at the Marginsâ

âIâve Always Loved the Magic at the Marginsâ

The problem I have, as I may have mentioned before, is that I act as a judge in a number of contests, so if I told you what I’m reading and what I’d recommend, I’d have to gag you until the winner announcements came out. For instance, last year I judged the delightful YA fantasy,

The problem I have, as I may have mentioned before, is that I act as a judge in a number of contests, so if I told you what I’m reading and what I’d recommend, I’d have to gag you until the winner announcements came out. For instance, last year I judged the delightful YA fantasy,

Witches fly on brooms and make wicked potions in boiling cauldrons, are associated with spiders and black cats, are often ugly and generally inclined to black clothing and pointed hats.

Witches fly on brooms and make wicked potions in boiling cauldrons, are associated with spiders and black cats, are often ugly and generally inclined to black clothing and pointed hats.