Last week a little piece at Mere Orthodoxy went semi-viral, at least among my smart Christian friends.

No surprise there. The article was titled, simply, “Against Pop Culture.”

Well! We can’t have that. Right? Especially when writer Brad East just came right out and said things like:

Reading, cooking, gardening, playing a board game, building something with your hands, chatting with a neighbor, grabbing coffee with a friend, serving in a food pantry, learning a language, cleaning, sleeping, journaling, praying, sitting on your porch, resting, catching up with your spouse or housemate: every one of these things would be a qualitative improvement on streaming a show or movie (much less scrolling infinitely on Instagram or Twitter).

There is no argument for spending time online or âengagingâ pop culture as a better activity for Christians with time on their hands than these or other activities. Netflix is always worse for your soulâand your mind, and your heart, and your bodyâthan the alternative.

Understandably, this opinion came across like a big ol’ foot stepping right on a few culture-engaging Christians’ wireless earbuds.

Why this ‘popular culture’ topic matters to us

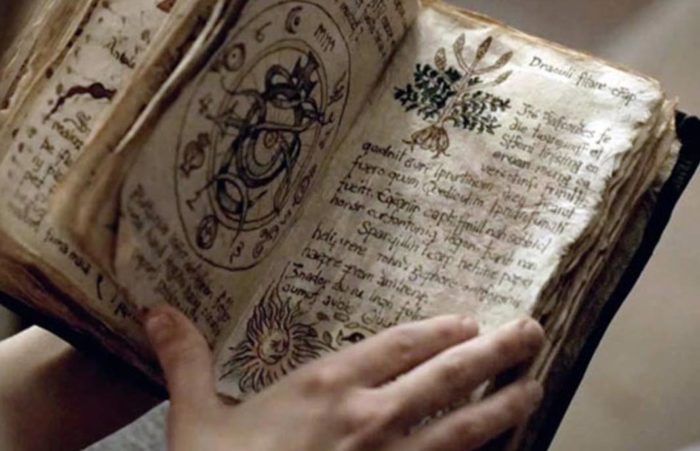

In theory, I should feel the same negative response. After all, I’m writing a book (with Ted Turnau and Jared Moore) on a related topic. It’s about how gospel-hearted families can raise their kids to engage popular culture for God’s glory. (Release target: spring 2020.)

For Christian fans of fantastical stories, this issues also matters.

We need to have some biblical and rational response to ideas like this, rather than simply sneer, “Ho-hum, another legalist.”

â E. Stephen Burnett

After all, our favorite stories make up this thing called popular culture. So if these stories are a waste of time, we’d best learn this early. And we need to have some biblical and rational response to ideas like this, rather than simply sneer, “Ho-hum, another legalist. Just like those nasty parents/church/youth leaders I learned to ignore.”

Instead my response is more mixed. Just as it would beâand I think should beâto any popular culture trend.

Joining me to explore our mutual response is Cap Stewart. He’s a contributor to the new book Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues. Cap has also written often, including here at SpecFaith, to challenge our assumptions about popular culture. Neither of us are strangers to Christian critiques of popular culture. But we also have some rebuttals to any re-reactive sort of “against popular culture” critique.

What ‘Against Popular Culture’ gets right

E. Stephen Burnett:

Okay! So I can finally sit down and jot out a few positive responses to that Mere Orthodoxy article.

Without getting into the author’s crucial follow-up, here’s what I did like about this “Against Pop Culture” piece:

(1) Diagnosis of the popular culture “lovefest.”

Some Christians have this lovefest when they grow up, move out, go to school, try a new church, and then realize, “Hey, folks, there’s a lot of pop culture around here. And get this: It’s not. All. Terrible. Like the Sunday school teachers/mom-n-dad said it would be!” (Well, on the one hand, I’m not sure Mom and Dad or the teachers actually said that. And I wish we’d be a little more discerning with our own memories.)

(2) A recognition that this leaves out some people.

All this “engaging popular culture,” as in the kind that goes on with young Christian thinkpieces and such-like, actually leaves people out of many conversations, rather than drawing them in.

Honestly, I skip maybe 80 percent of these thinkpieces for this very reason: I don’t actually follow all that much of what’s ragingly popular in our culture (e.g., America). The internet and specialized fandom/interest groups is a cause of this. I’ve found my favorite genres and stories and franchises, at least in visual media, and by and large, I stick with those. It’s actually rare that I branch out.

(3) A basic observation that popular culture consumption can become a waste of time.

This is, frankly, a monster-lurking-in-plain-sight that many articles and books with titles like Finding the Gospel in XYZ just don’t address explicitly. If they do, it comes off as more of a “Now, of course we don’t want to overdo this …” type of disclaimer. It sounds like the reverse of the kind of thing a genteel legalist would say when he says, “Now, of course we know that ‘entertainment’ can be harmless …” before following it with a great big “Buuuut …”

Cap, what did you like about the article, and/or think that it began to approach well?

Cap Stewart:

After reading the piece several times, and trying to view it with as charitable a position as I can, there are a few points I can appreciate.

First is the acknowledgement of extremes: how overprotective guidelines for children (whether provided by parents or some other authority structure) can lead to a pendulum swing later in life that is too far in the other direction. If one grows up under a strict art-aversion paradigm, art indulgence might feel like the proper solution. Or, to put it another way, when one is told not to engage with pop culture in any way, they may eventually feel that the proper stance is to engage with pop culture in every way.

A second element I can appreciate is Eastâs well-meaning but ill-suited push-back against indiscriminate indulgence in entertainment. If our Christian subculture is leaning in error, I think it is toward the indulgence end of the spectrum rather than the avoidance end. And if indulgence is the main problem, it should be addressed more often and more readily than it is. Addressing the dangers of avoidance when indulgence is the prevalent is dangerously myopic.

Our enthusiastic embrace of pop culture can be a sign of outright idolatry. We are quick to follow entertainment as our own personal pied piper.

â Cap Stewart

A third element, closely related to the second, is the idea that our enthusiastic embrace of pop culture can be a sign of outright idolatry. We are quick to follow entertainment as our own personal pied piper, even if said entertainment leads us right off the cliff of banality (to paraphrase a different, and much more godly Piper).

What ‘Against Popular Culture’ seems to ignore

Cap Stewart:

The problems I have with the article, however, outweigh the positives. All of the above points are either only hinted at or buried under much needlessly hyperbolic language. East paints with such a broad brush that he fills his article with the wrong color. His sweeping generalizations distract from the heart of his message.

I have no problem with click-baity titles if they arenât deceptive and actually deliver the goods. As a rare exception, âAgainst Pop Cultureâ is problematic because it does deliver the goods: it actually makes East come across as (basically) being opposed to all forms of pop culture. There are âno good reasons,â he says âfor why Christians (or anyone) ought to be enthusiastic consumers of pop culture.â He also says, âNetflix is always worse for your soulâand your mind, and your heart, and your bodyâthan the alternative.â Elsewhere, he says to care about engaging with pop culture is âa silly thing to believe, and the silliness should be obvious.â None of these are helpful statements.

Thereâs also the confusion displayed in the article about what exactly constitutes pop culture. According to East, we are to forsake pop culture and do other, more important things, including (among other things) reading and playing board gamesânot to mention activities like chatting with a neighbor, grabbing coffee with a friend, and catching up with your spouse or housemate (all of which could very well involve discussions about popular culture).

When all is said and done, this article, as it stands by itself, seems tailor-made for the phrase âthrow the baby out with the bathwater.â Yes, thereâs a lot of dirty water here, and we need to drain the tub (so to speak). Yet if extreme and indiscriminate indulgence in pop culture is unhealthy (and it is, and it must be addressed), so is the extreme and indiscriminate opposition to all pop culture. We canât be just wise as serpents or innocent as doves; we need to be both.

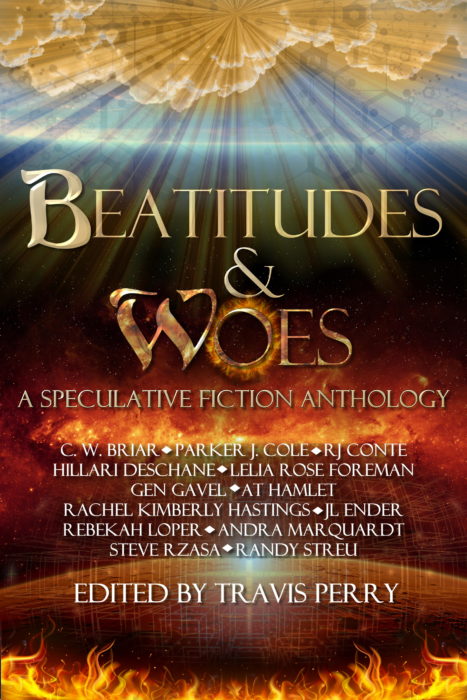

I am all for exercising temperance when engaging with pop culture. A large portion of my research and writing over the last several years has been cautionary in nature. Heck, my essay in the recently released anthology Cultural Engagement is entitled, “When Art Becomes Sin.” It appears that East and I agree that the church’s standards on pop culture engagement have been severely compromised. I just think there’s a lot of collateral damage with the approach East has chosen to take in this piece.

I am all for exercising temperance when engaging with pop culture. A large portion of my research and writing over the last several years has been cautionary in nature. Heck, my essay in the recently released anthology Cultural Engagement is entitled, “When Art Becomes Sin.” It appears that East and I agree that the church’s standards on pop culture engagement have been severely compromised. I just think there’s a lot of collateral damage with the approach East has chosen to take in this piece.

What Christian popular culture writers also seem to ignore: a biblical argument for popular culture’s purpose

E. Stephen Burnett:

I agree with your positive reading and yet also your “baby with the bathwater” concerns. But some of the critiques I’ve read seem to come from a position of reaction based on personal experience. In other words, people may say things like, “I grew up being taught (or catching from the evangelical cultural winds) the notion that popular culture = evil, and this article is just more of the same.”

Well, this doubles down on a very flawed approach to anything, based on personal experience and personal association. Either the “against pop culture” or the “against religious legalism” folks are starting with the same word: “against.” In other words, their beliefs begin with a subconscious assumption that something has gone wrong with this “world” and we must fix it. In a gospel paradigm, however, that starts too late. You’ve missed a “chapter 1” of the story. Instead we must go back to that first chapter and ask, “what was originally right?” That’s an argument based in proactive truth as defined by our Creator, rather than reaction to “the bad guys.”

In this case, East (both in his original article and in the followup) seems disinterested in the origins of popular culture in the first place. There’s no effort to engage with popular culture’s biblical purpose (if it has one) or popular culture’s place in God’s economy.

Unfortunately, though, some of his critics make the same flawed judgments. So we end up circling the same questions of whether engaging/not engaging popular culture will endear us to certain persons or help us be better neighbors with them in order to affect our culture.

These are vital questions, but they are secondary. Only if the Christian’s “chief end” is “to evangelize the lost” would these questions be of utmost importance. But this is not our chief end. Instead, our chief end (per the Westminster Shorter Catechism) is “to glorify God, and to enjoy him forever.” This leads to the highest priority when engaging with anything in this world: how ought we do/not do this thing to the glory of God?

East’s followup article offers a lot of important clarifications. He makes this vital point:

I’m rejecting the case made by far too many Christian writers, academics, and pastors that their fellow Christians should be engaging pop culture. As I wrote, that is silly, and its silliness should be dazzlingly apparent to all of us.

If we as Christians write about popular cultureâthat is, human stories and songs, usually delivered via technologyâwe must insist on putting the “biblical purpose of human culture” material up front. We must show our work.

â E. Stephen Burnett

On this I agree. In fact, some writers’ proâpopular culture materials carry a tone as if to say, “Hey hey you guys popular culture ISN’T EVIL!1!!” These also tend to ignore any biblical purpose of culture, and strike me as at best happily sophomoric, or at worst willfully naive about the idols and vapid trends pervading popular culture.

Here, perhaps East has explored the “biblical origins of culture” question elsewhere, and it’s at the back of his body of work. But at this point, I don’t think we can afford to limit this concept to the footnotes. If we as Christians write about popular cultureâthat is, human stories and songs, usually delivered via technologyâwe must insist on putting the “biblical purpose of human culture” material up front.

We must show our work:

- That we have considered the biblical origins of human culture-making (based on the cultural mandate) of Genesis 1:28,

- God’s original purpose in giving us this gift,

- How this gift is affected by the Fall,

- How the Old Testament saints built culture (even popular culture) for God’s glory.

Even more importantly, now that Christ has come and we live in the Church age, we must explore how Christians see popular culture in light of Christ’s redemption. This will include (but isn’t limited to) popular culture’s role in the Great Commission. Finally, we must see in light of eternity, the future and physical New Heavens and New Earth, what role popular culture may have in the Kingdom. Because, frankly, if we don’t at least suspect that some popular culture may (literally and physically) last forever, why bother with it now?

However, I do think these themes will challenge East’s original audience more than folks like him who purport to be “against pop culture.” E.g.:

I had at least two audiences in mind with my original piece. One was the group criticized directly: those who believe, and write, that Christians ought to “engage” pop culture. And the reaction of at least some folks proved, to me at least, the point: there is a kind of nervous insecurity on the part of folks who “love” pop culture and who therefore need it to Be Meaningful . . .

Regarding this, we are on the same team. You don’t need popular culture to Be Meaningful in order to fit in with the Jonesesâeven if your intent is to evangelize the Joneses.

However, the first flaw here isn’t in such a well-meaning Christian’s over-baptism of popular culture.

The flaw appears in the Christian’s insistence on trying to be the good-cop Christian, that is, the Christian who will not condemn popular culture (like all those bad-cop Christians that he and the unsaved neighbors surely know about, right?). And the flaw is in the Christian’s belief that his chief end is to represent Jesus to his neighbors. Not so. His chief end is to glorify God and enjoy God foreverâwhich includes representing Jesus to the neighbors. He who would be a great and non-legalistic Christian, to help lead the unsaved masses, must first be God’s servant. And this primary role must lead us back to those old and un-hip questions based in personal piety and purity.

All things streaming on Netflix may be permissible, but not everything is beneficial (1 Corinthians 10:23). In that text, Paul isn’t primarily interested in how we participate in cultural activities based on our witness to the watching world. He’s interested in whether we are being personally idolatrous or holy.

Are Christians always ‘counter-cultural’?

Cap Stewart:

You make some good points. And it is right that we need to go back to “chapter 1” of God’s story in order to better understand what was true and right and good about God’s created order before we can effectively critique.

It’s much more easy to be “against” something without doing the legwork of appreciating what to be a proponent of. (I can be guilty of this myself, as much of my cultural commentary is on what is wrong with certain aspects of it. Even in my opposition, I need to make sure I communicate what I am for as well as what I am against.)

Not to be too dramatic, but that’s actually a Satanic strategy. He can’t create anything good to begin with. He can only work against the good that God has created by perverting it. Satan’s whole identity, in fact, is wrapped up in what (or, rather, who) he is against. He’s not for anything.

E. Stephen Burnett:

Amen! And speaking very frankly, living this kind of anti-based life is no way to train for eternity.

And this tendency is behind any argument based on “counter-culture.”

Former generations of Christians were “counter-culture” versus, say “Big Hollywood,” or MTV, or boycotts against Disney.

Now, their children (having become adults) happily adopt that “counter-culture” mindset, but mainly turn it against Christian cultures.

Either way, the starting point remains the same: “Let’s not be bad guys.”

Rather than, “Let’s be worshipers of God according to his holy revelation.”

Cap Stewart:

Indeed. And the thing is, on the surface, it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference between the two. After all, a properly robust Christian worldview will be quite counter-cultural.

E. Stephen Burnett:

In some ways, yes. In other ways, perhaps not.

For example, have you noticed how “the culture” is at once still encouraging promiscuous dress but also resisting the sexual exploitation of female heroes in fantastical movies? A Christian with an ethic of “Look at what The Culture is doing, then do the opposite” would be very confused here. Because human culture is like many humans themselves–hopelessly (apart from Christ) mixed up. A hot mess.

Cap Stewart:

Yeah, C. S. Lewis (via Screwtape) pointed out that humans have the capacity to adhere to conflicting views/convictions without even realizing it. It’s something we all do–to a certain degree, at least.

How then should Christians critique popular culture?

E. Stephen Burnett

On that note, let’s strive to treat Christian critiques of popular cultureâand critiques of “Christian popular culture engagement”âin the same way. Let’s consider them carefully and thoughtfully, rather than reacting as if to say, “Oh, no, here we go, another legalist on the scene.”

With that in mind, and with your recent published essay in Cultural Engagement in view, how do you think that Christians ought to critique popular culture?

What are some healthy worldview tenets, holiness guidelines, and any other principles to follow?

Cap Stewart:

Those are good questions. As a partial answer, I think your point earlier, that we must discern Godâs original intent for all of creation (including popular culture), is important to remember.

In his manifold wisdom, God created man in His own image to reflect and glorify Him. Partâthough certainly not allâof our image-bearing work includes creation: the development of industry, arts, customs, and the like (i.e., culture). As image-bearers of our creator, we can express His redemptive purposes through cultural development.

Yes, the Fall has affected all areas of our lives, and sin taints even our best efforts. But Godâs original intent for his gifts remains, and it can be viewed through expressions such as hard work and recreation, faithful pursuits of singleness and marriage, expressions of justice and mercyâand the development of culture through such means as the arts, entertainment, and technology.

Based on an eternal perspective, it is reasonable to assume that our mandate to share and reflect Godâs image will continue in the new heavens and the new earth.

â Cap Stewart

The cultural mandate is just thatâa mandate. It is a divine commission. We cannot adequately reflect Godâs image apart from it. And based on an eternal perspective, it is reasonable to assume that our mandate to share and reflect Godâs image will continue in the new heavens and the new earth.

To be sure, it is foolhardy to extrapolate that all forms of culture making (and culture critiquing) are equally valid and equally admirable. (They are most certainly not. Some deserve to be praised and some deserve to be condemned.) It also foolhardy, however, to condemn all forms of culture (including pop culture) as inherently invalid and irredeemable. The Christianâs endgame should be informed by the endgame of the kingdom of God. And in Godâs wisdom, He advances his kingdom in part through the advancement and development of culture.

Toward that end, I think itâs imperative to remember our Saviorâs encapsulation of the Christianâs duty: to love God with our whole being, and to love our neighbors as we love ourselves (Mark 12:28â32). This can help us both as we look inward (to evaluate our own heartâs posture) and as we look outward (to praise or critique aspects of pop culture). There are legitimately complex areas that require a nuanced approach (although I think there are fewer such instances than the current consensus permits). Still, if we donât start with Christâs summary of the law, the eyes of our hearts will incorrectly perceive a plethora of shades of gray, and will miss many of the vibrant colors and stark black/white contrasts revealed to us through Scripture.

Cap Stewart is an independent business owner and freelance writer. He’s been a fan of speculative fiction ever since picking up This Present Darkness in fifth grade, and his beloved gamer bride makes up for whatever nerdom he lacks. Cap is a contributing writer to the book Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues (Zondervan, 2019). He also blogs at Happier Far.

Cap Stewart is an independent business owner and freelance writer. He’s been a fan of speculative fiction ever since picking up This Present Darkness in fifth grade, and his beloved gamer bride makes up for whatever nerdom he lacks. Cap is a contributing writer to the book Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues (Zondervan, 2019). He also blogs at Happier Far.

But what about the normalization process? I guess I’d add another layer of discernment or awareness: what things might be problems for the culture, for society at large? For instance, was the violence in Schindler’s List an encouragement of mass murder? I don’t see how. Was the promiscuity on display in Mash an undermining of monogamous marriage? I think it was. Was Harry Potter normalizing witchery? Not in the least.

But what about the normalization process? I guess I’d add another layer of discernment or awareness: what things might be problems for the culture, for society at large? For instance, was the violence in Schindler’s List an encouragement of mass murder? I don’t see how. Was the promiscuity on display in Mash an undermining of monogamous marriage? I think it was. Was Harry Potter normalizing witchery? Not in the least.

Pixar had sold its birthright for a mess of pottage. Nonetheless, I went to see it when it came out. Even Pixarâs mediocre efforts are solidly pleasant, and just because I know their game of nostalgia doesnât mean I wonât play. I got more than I came for; I thoroughly enjoyed Toy Story 4. It is true, though possibly faint praise, that Toy Story 4 is easily the best Pixar movie since Inside Out.

Pixar had sold its birthright for a mess of pottage. Nonetheless, I went to see it when it came out. Even Pixarâs mediocre efforts are solidly pleasant, and just because I know their game of nostalgia doesnât mean I wonât play. I got more than I came for; I thoroughly enjoyed Toy Story 4. It is true, though possibly faint praise, that Toy Story 4 is easily the best Pixar movie since Inside Out.

Cap Stewart is an independent business owner and freelance writer. He’s been a fan of speculative fiction ever since picking up This Present Darkness in fifth grade, and his beloved gamer bride makes up for whatever nerdom he lacks. Cap is a contributing writer to the book Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues (Zondervan, 2019). He also blogs at

Cap Stewart is an independent business owner and freelance writer. He’s been a fan of speculative fiction ever since picking up This Present Darkness in fifth grade, and his beloved gamer bride makes up for whatever nerdom he lacks. Cap is a contributing writer to the book Cultural Engagement: A Crash Course in Contemporary Issues (Zondervan, 2019). He also blogs at

At one point, I began a

At one point, I began a  Here’s another example. After I read J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, I began a search for another author, similar to the one who had penned a story I loved. This pursuit was particularly necessary because there were no other Tolkien books on the horizon at that time. A friend suggest I try Stephen Donaldson’s Wounded Land trilogy. After a false start with the first book, I was hooked.

Here’s another example. After I read J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, I began a search for another author, similar to the one who had penned a story I loved. This pursuit was particularly necessary because there were no other Tolkien books on the horizon at that time. A friend suggest I try Stephen Donaldson’s Wounded Land trilogy. After a false start with the first book, I was hooked.

Greatness eluded me. It wasn’t for a lack of effort or potential, as far as I could tell. I just couldn’t shake the feeling I’d taken a wrong turn somewhere and couldn’t find my way back.

Greatness eluded me. It wasn’t for a lack of effort or potential, as far as I could tell. I just couldn’t shake the feeling I’d taken a wrong turn somewhere and couldn’t find my way back. Steve grunted. He had his back to me, nestled in his makeshift art studio wedged in the three-foot space between the living room couch and the kitchen counter. Beyond his tweed fedora that caged a smoothed, black pony tail, a dark paint brush struck mercilessly against his latest art piece. Swirling layers of thick black and grey oil on canvas grew more devoid of hope by the minute. A lone figure with an inner luminescence walked through his painted darkness toward a keyhole-sized beam of light in the distance. I held little hope he would make it.

Steve grunted. He had his back to me, nestled in his makeshift art studio wedged in the three-foot space between the living room couch and the kitchen counter. Beyond his tweed fedora that caged a smoothed, black pony tail, a dark paint brush struck mercilessly against his latest art piece. Swirling layers of thick black and grey oil on canvas grew more devoid of hope by the minute. A lone figure with an inner luminescence walked through his painted darkness toward a keyhole-sized beam of light in the distance. I held little hope he would make it. Paul Regnier is a speculative fiction author perpetually lost in daydreams of spaceships, magic, and the supernatural. He is the writer of Paranormia, an urban fantasy/supernatural comedy, and the

Paul Regnier is a speculative fiction author perpetually lost in daydreams of spaceships, magic, and the supernatural. He is the writer of Paranormia, an urban fantasy/supernatural comedy, and the

upernatural manifestations of power which do not come from God come from Satan. There is no such thing as “good magic” in real life.

upernatural manifestations of power which do not come from God come from Satan. There is no such thing as “good magic” in real life.

Sponsored Review: Logicâs End

Sponsored Review: Logicâs End Featured Review: Light from Distant Stars

Featured Review: Light from Distant Stars How the Psalms Reflect our Heart Desires

How the Psalms Reflect our Heart Desires Letâs Guard Against Temptations in YA Fiction

Letâs Guard Against Temptations in YA Fiction

Topics at the Conference range from marketing to editing, world-building, self-publishing, agenting, screenwriting, and more. It sounds like a broad range of subjects, so writers at various levels of experience can find something helpful.

Topics at the Conference range from marketing to editing, world-building, self-publishing, agenting, screenwriting, and more. It sounds like a broad range of subjects, so writers at various levels of experience can find something helpful. And still there is more. Besides optional meals with faculty, the Awards Dinner will be held Friday night. Not only are the winners of various contests announced but conferees may dress in costume.

And still there is more. Besides optional meals with faculty, the Awards Dinner will be held Friday night. Not only are the winners of various contests announced but conferees may dress in costume.