Ming the Merciless. Image Credit: Villains Wiki.

Once upon a time in speculative fiction (say in the heyday of Flash Gordon, first published in 1934), most storytellers wrote as if good was good and evil was evil. Writers might use speculative fiction to explore the nature of good and evil by attempting to distill the purest imaginable form of each and set them at war with one another (which is arguably one of the great achievements of The Lord of the Rings) but nobody had to explain why the villain was villainous–Sauron and Ming the Merciless were just bad, period. That “once upon a time” has mostly disappeared–villainous characters today are often given sympathetic backstory treatment which explains how they suffered some form of tragic circumstance which transformed them into the evil being they became. And it happens to be that I’m mostly against the tragic villain backstory as a storytelling device. I’m about to tell you why.

First let me give some credit where credit is due. In some of the old tales of speculative fiction, good and evil were often distilled out to the point where they became…well…really corny. The villainous laugh of the over-the-top baddie not only is a bit silly, it really hasn’t been all that common among historical bad guys (though if, say, Ivan the Terrible were to be laughing at you, you could be sure that you were in deep, deep, deep, deep trouble–so villainous laughter really has been “a thing” sometimes). Plus, isn’t it actually true that most people are a blend of good and evil impulses? Isn’t it fascinating to see a character who exemplifies both virtuous traits like courage and charisma while at the same time being a heartless butcher and abuser of oppressed people? (I’m thinking of you, Gul Dukat, Star Trek Deep Space Nine.)

Gul Dukat

Image Copyright: CBS

Yeah, in many ways, storytelling has become richer in certain aspects by exploring people who are shades of gray and by showing how circumstances can lead a person to switch from one side of the equation to the other…though even the cheesy Flash Gordon stories occasionally showed a good character tempted by evil or a bad character helping someone good. And The Lord of the Rings did this very well at times, showing dividing lines between good and evil in complex ways in places within the narrative, including how Frodo was drawn to evil by the power of the Ring, while Gollum was drawn back the other way.

So my objection to the modern villain’s tragic backstory is not that I’m protesting “gray” characters–at times such characters are very interesting (though I also like good and evil in purer versions at times, too). Nor am I objecting to characters shifting over time in either the direction of evil or the direction of good.

I am a bit put off by the presumption that people are by default good and something needs to happen to make them bad that I see in a tragic villain backstory. No, people in my belief and observation generally have both altruistic and also selfish impulses and while that doesn’t make everyone literally totally depraved (as in Five Point Calvinism) that does make all people helpless to expunge themselves of every form of selfishness by self-effort. People can get better by effort of will, but cannot get all the way good. You can find some few human beings in history who show nothing but utter contempt for other humans at all times, even though that’s quite rare. But I cannot think of any human being who has always been completely altruistic in all moments of life, not even Mother Theresa. In general, human beings round down to bad rather than up to good and in fact someone being a very good person requires a great deal of education and modeling of the example of others, not to mention an extra helping of natural empathy. All things considered, I would say that someone being very good requires more of a story explanation than someone being very bad–though getting this wrong is not what bothers me most about the tragic villain backstory.

What I most find offensive about a tale like Oz, The Great and Powerful, which shows the Wicked Witch of the West becoming evil because of romantic jealously, or Maleficent, which shows the wicked sorceress turn bad because of the a love interest who dies, or the recent Joker movie, which shows the villain (played by Joaquin Phoenix) as an emotionally fragile misfit who turns dark due to a series of slights and misfortunes, is the role these stories assign suffering. Suffering, hardship, something going wrong, someone abusing you–this is what these movies portray as producing evil.

Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker.

Image Credit: GeekTyrant

Why do I find that offensive? Well, not only because I have a rather tragic backstory myself in some ways (and I’m pretty sure I’m not a supervillain), but some of the greatest of all heroes are suffering heroes. Suffering can be the ultimate demonstration of love–Jesus Christ carrying the cross to the place of the skull–Frodo carrying the Ring up the slopes of Mount Doom–both barely able to move under the weight of their burden. Suffering can also deepen empathy and teach someone who never really had any tragic experiences how hard life is for some who walks in different shoes.

Suffering often drives people towards faith in God–many of the poorest and most suffering people in the world are also the most devoted to God, and often are very genuinely kind and gracious people. Yes, rough neighborhoods produce thugs, too, and poor countries can also be violent ones. Yes, sometimes suffering really does seem to harden people and make them worse than they otherwise would be. Yet passing through a great deal of suffering isn’t the most common profile of the scariest people who have ever lived on Planet Earth.

The scariest people on the planet are those willing to make others suffer, while avoiding all forms of hardship themselves. Yes, sometimes this sort of person is born into a rough neighborhood and looks around and notices that joining up with bad men will help protect him from harm–and he is willing to be cruel to others in order to avoid suffering hardship himself (using masculine pronouns because it’s almost always men who fall into this particular pattern of behavior).

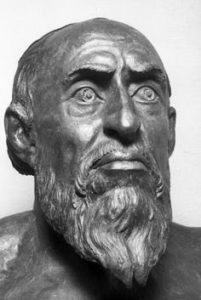

But sometimes the worst of the worst are born into privilege and start life with inordinate power. Not having ever deeply suffered themselves, they view the suffering of others with contempt. Caligula and Nero grew up with this kind of power–and grew up in utter indifference to the hardship of others. Ivan the Terrible likewise, while he did suffer hardship and loss at times, was raised to believe he literally represented God on Earth. He believed for a time that he could do no wrong–he believed he was different from all other human beings–and that the lives and needs of other people were not as important as his wants, needs, and desires. Plus of course, some of the worst of the worst not only are poorly raised to see themselves as the center of the universe, they also lack natural empathy for a variety of reasons.

Ivan IV (the Terrible) of Russia. Forensic facial reconstruction by M.Gerasimov.

Note that I’m offering an opinion here about the true nature of evil, but I think it’s a solid one. The wickedness within the human heart springs forth far more when people are handed the power to damage others than when a person is helpless before the cruelty of other human beings. Helpless, suffering people may indeed become bitter and lash back, but normally, it’s those who are not themselves suffering, in an environment where suffering is commonplace, who have something to gain from making others hurt, who show the true depths of wickedness that our species is capable of.

Can I back up my opinion with science? To a degree, yes. Scientific studies on the nature of evil in general would be unethical, but one of the major ones that has taken place, the Stanford Prison Experiment conducted by Philip Zombardo in 1971, in which students were divided into two randomly-selected groups, one of which were prisoners and the other, prison guards, showed those in power turning sinister, not those suffering. Philip Zombardo in fact sees evil strictly in terms of this kind of environment of power imbalance as he explains in his book The Lucifer Effect—I disagree with him about that, because I see evil having multiple causes, but I do agree that an environment where people are given inordinate power over others who are suffering does far more to produce villains than people going through hardship themselves.

Historical events also have demonstrated how the seeds of evil in the human heart (through sin) sprout and grow in an environment of unlimited power over the lives of others. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn noted in his books on Soviet prison camps, The Gulag Archipelago, how guards in power routinely performed evil actions–though he also saw that an ideology justifying cruelty made people worse than power alone:

“The imagination and spiritual strength of Shakespeare’s evildoers stopped short at a dozen corpses. Because they had no ideology. Ideology â that is what gives evildoing its long-sought justification and gives the evildoer the necessary steadfastness and determination. That is the social theory which helps to make his acts seem good instead of bad in his own and others’ eyes…. That was how the agents of the Inquisition fortified their wills: by invoking Christianity; the conquerors of foreign lands, by extolling the grandeur of their Motherland; the colonizers, by civilization; the Nazis, by race; and the Jacobins (early and late), by equality, brotherhood, and the happiness of future generations…”ââThe Gulag Archipelago, Chapter 4, p. 173

But concerning his own suffering in the Gulag, Solzhenitsyn said: “Bless you prison, bless you for being in my life. For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul.”

So if we as authors wish to portray ordinary people (commonly considered good, though they aren’t entirely) becoming blatantly evil because of circumstances, let’s pick the right circumstances. Tragedy and suffering are often ennobling. Whereas power over others made worse when backed by an ideology that justifies treating others cruelly–that is the sort of backstory that routinely cranks out villains. Not tragic events, not suffering and loss–not usually.

written like narrative, but they are not narrative. Flashbacks disrupt the story, breaking up the flow and momentum of events to reprise old news. I have seen them done well, but I have also seen them done with extraordinary badness. Not all authors appreciate the nature or the purpose of the technique.

written like narrative, but they are not narrative. Flashbacks disrupt the story, breaking up the flow and momentum of events to reprise old news. I have seen them done well, but I have also seen them done with extraordinary badness. Not all authors appreciate the nature or the purpose of the technique.

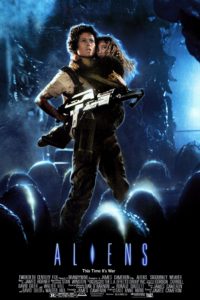

Realm Makers actually has two different kinds of awards. First is the type that is similar to other award organizations, only the categories involve speculative titles. Here are the three finalists for the Realm Awards—“among the best speculative titles published in 2018”—which will be presented during the Realm Makers Conference dinner:

Realm Makers actually has two different kinds of awards. First is the type that is similar to other award organizations, only the categories involve speculative titles. Here are the three finalists for the Realm Awards—“among the best speculative titles published in 2018”—which will be presented during the Realm Makers Conference dinner: The Blue Ridge Mountains Writers Conference offers the

The Blue Ridge Mountains Writers Conference offers the

Those things are secondary to the wants/needs understanding. If a character like Grady wants to be loved, then how does that affect his choicesâhis aspirations, the way he dresses, what he does with the hours in his day, the type of job he seeks, and so on.

Those things are secondary to the wants/needs understanding. If a character like Grady wants to be loved, then how does that affect his choicesâhis aspirations, the way he dresses, what he does with the hours in his day, the type of job he seeks, and so on.

Some of the science fiction ideas came less from imagination and more from an awareness of the current direction science was heading. Electric cars, for instance, popped up in 1969 in John Brunnerâs novel Stand on Zanzibar. Aldus Huxley, influenced by J.B.S. Haldane, wrote, in his novel Brave New World, about a world dependent upon what we now call in vitro fertilization.

Some of the science fiction ideas came less from imagination and more from an awareness of the current direction science was heading. Electric cars, for instance, popped up in 1969 in John Brunnerâs novel Stand on Zanzibar. Aldus Huxley, influenced by J.B.S. Haldane, wrote, in his novel Brave New World, about a world dependent upon what we now call in vitro fertilization. George Orwell in his novel 1984 married future technology with societal changes, envisioning a world divided into three states based on location. The one known as Oceania was ruled by Big Brother who controlled the population by a sophisticated system of surveillance. From this authoritarian control came unreliable or “fake” news intended to deceive, not enlighten, the public. Along with this effort the Ministry of Truth regularly modifies photograph (photoshops pictures) to portray what they wish, Orwell’s novel introduced the Thought Police which is a forerunner to the politically correct climate of western culture today.

George Orwell in his novel 1984 married future technology with societal changes, envisioning a world divided into three states based on location. The one known as Oceania was ruled by Big Brother who controlled the population by a sophisticated system of surveillance. From this authoritarian control came unreliable or “fake” news intended to deceive, not enlighten, the public. Along with this effort the Ministry of Truth regularly modifies photograph (photoshops pictures) to portray what they wish, Orwell’s novel introduced the Thought Police which is a forerunner to the politically correct climate of western culture today.