Characters And Their Development: From The Writers’ Tool Chest

So often writers of speculative fiction focus on worldbuilding, and rightfully so. When a story takes place in outer space or on a planet far, far away, or in a pretend world, or in our world in a future time, the world the author creates must be realistic, believable, textured. But the truth is, characters still make the story, even in our imagined worlds.

For all our intriguing Other Places, readers still read because they care about the characters. I wrote about this nearly three years ago, particularly addressing the way Christian writers portray non-Christian characters. But in truth we need to deepen our understanding of how to develop all our characters.

Here is an excerpt from Power Elements Of Character Development which introduces this topic of developing our characters:

Fundamental to any good novel is a good character, but what makes a character “good”?

When I first started writing, I had a story in mind, and my characters were almost incidentals. Since then, I’ve learned how flat such a story is. Characters make readers care about the events that happen, but in turn, the events are the testing grounds which allow characters to grow.

So which comes first? I believe that’s an immaterial question. A good story must have both a good plot and good characters—the non-flat kind.

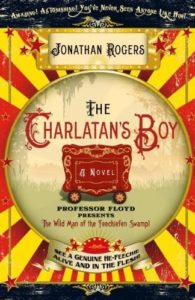

In developing main characters, a writer needs to give each something he wants and something he needs. The “want” is generally outside him (to destroy the One Ring, to marry Ashley Wilkes, to escape the Safe Lands), and the need is that internal thing that drives him (to find purpose, to do the right thing, to be loved). The internal may not be something the character is aware of consciously. For example, in Jonathan Rogers’s excellent middle grade novel The Charlatan’s Boy, young orphaned Grady doesn’t go around saying, I need to be loved and accepted, but the reader fairly quickly understands this about him.

Secondly, having given the protagonist a want and need, the author must also put him on a path to gain what he wants. However, as the story moves forward, this initial want may change. If the character wants to reach point A, he may discover upon arrival that his need is not met, so he now sets out to reach point B. Or, along the way he may realize that he only thought he wanted A, but in actuality wants B; consequently, he abandons the quest for A and aims for B.

Another important aspect of character development is the increase of a character’s self-awareness. The protagonist should have strengths and weaknesses, and as the story progresses, his understanding of how to use his strengths and/or change his weaknesses should expand.

Fourth, the character should make progress, both in achieving what he wants and acquiring what he needs. Yet success can’t come too easily or there really is no story. But to make no progress defeats the character, and the reader, dyeing the story in hopelessness.

Notice that all these first character development points have little to do with hair style or eye color. Often those are the things writers settle on as the most important when they start putting a character together. Is he tall? Does he like football? Is she a shopper?

Those things are secondary to the wants/needs understanding. If a character like Grady wants to be loved, then how does that affect his choices—his aspirations, the way he dresses, what he does with the hours in his day, the type of job he seeks, and so on.

Those things are secondary to the wants/needs understanding. If a character like Grady wants to be loved, then how does that affect his choices—his aspirations, the way he dresses, what he does with the hours in his day, the type of job he seeks, and so on.

Part of understanding these aspects of the character depends on the personality of this individual. Is he a “can do” sort, so he looks at obstacles as challenges, or is he burdened by his wants and needs, fighting to keep from despair?

Notice that in either instance, the character is fighting. In contrast, a character who takes a passive approach to life as opposed to taking action, is not someone readers will connect with easily.

One more important element—a writer needs to think of his character as an individual. What are the quirks that he has that no one else has? Or the gestures, the speech patterns, the thinking style?

Know your character, inside and out. Then put him in any circumstance you wish, and you will know what he will do. Someone as spacey as your character would do something silly when the pressure’s on. Someone shy and retiring would never make herself a spectacle but would probably have a favorite get-away spot where she hides from the world.

Throughout the story, authors test their characters and grow them and change them so that in the end they do more than even they thought possible.

Yeah, people shouldn’t act like they need to choose between plot and characters. Like, maybe one takes more precedent than the other at times, but that’s more on a per author or per story basis. It’s usually best to play the plot and character off of each other during development, since that can make it easier to get out of creative ruts and whatnot.

Another aspect is not to leave side chars in the dust when it comes to development(at least whenever possible). Every person has their own desires, agendas, etc, and whether or not the chars are good people, their agendas will often clash and drive the plot. So if something in the story stagnates or feels shallow, it may be that the side chars and their interactions with others are underdeveloped.

Underdeveloped is a good way to say it, Autumn. I’ve used the term cardboard characters or placeholders. They don’t seem like real people but like cardboard dolls that the author needs to do something so the protag can accomplish or fail or whatever the author wants to happen. The best stories make the characters feel like real people.

Becky

Yeah, especially when the underdeveloped side chars are pretty much just designed to prop up the main char. (Often by praising/befriending the main char to make them look good, or by being a straw man that bullies the main char just to make the main char look sympathetic). That tends to lead into Mary Sue territory, and most people don’t want their main chars to be Mary Sues.