(This series is based on our ongoing email conversation between author Fred Warren and myself, about icons in the Bible, church history, and present-day stories.)

(This series is based on our ongoing email conversation between author Fred Warren and myself, about icons in the Bible, church history, and present-day stories.)

Fred,

Just last week, this series became more current, and not only because of Resurrection Sunday, about the only true âicon,â our risen Savior, Jesus Christ. I say this because a certain entrepreneur and painter, very popular in the evangelical world, happened to pass away on Good Friday, April 6.

That would be Thomas Kinkade, whom you had mentioned in the email you had already written. And though I will broach only the topic of Kinkadeâs artwork â not his motives or personality â below, I know this may be a more-controversial topic.

Thatâs because how we view icons relates to how we enjoy, or critique, a painting like the kind(s) Thomas Kinkade made. It also relates to the idea of growing into an icon.

Icons are inevitable

Though this series has brought some varying views, so far we have not disagreed on anything. It seems most readers, too recognize that icons â i.e., symbolic or graphical representation of a larger series of truths or ideals â are inevitable in our lives.

Whether we look at the history of the Church, modern-day stories, or the Bible itself, we canât help finding those simple, recognizable icons that are âimplantedâ in our minds.

And it would seem those who are not aware of how this concept works may likely be taken advantage of, by storytellers, artists, and even ad-makers. (This makes me nearly wonder if that long-since-discredited âsubliminal messageâ conspiracy theory was itself the real conspiracy theory, to distract us from how artists may really influence people!)

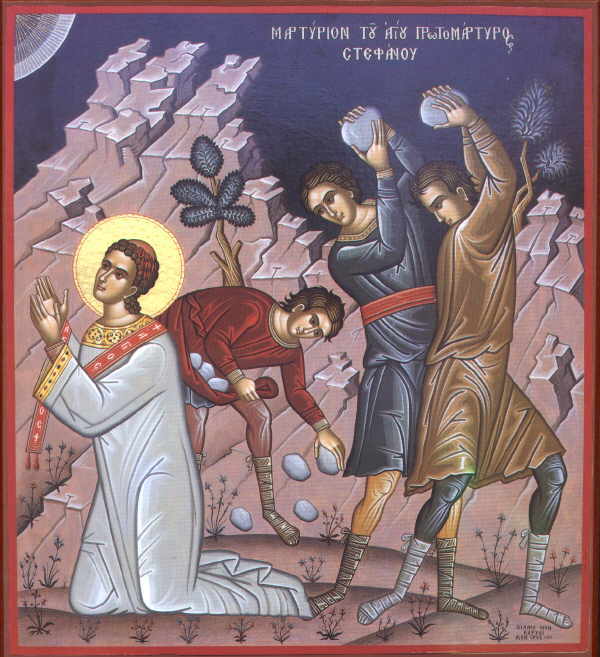

This is by no means unknown to the Christian world. We may not have necklaces with Masonic symbols, or simple-lined, flat-colored artwork, like the representations of Jesus Christ that you have included in part 1 and part 3 of this series. But we do have icons.

As you wrote in part 3 on Tuesday:

I think most people never realize this. We Protestants have scrubbed our religious culture of obvious icons, but have become tone-deaf to the meaning and power of the iconic images weâve gathered to fill that void, many of which send incoherent messages or clash with one another because theyâve been adopted without much thought. Iâve seen some references to the plasma screen as a modern Protestant icon.

This is the first time Iâve heard of the plasma screen in that context. But it makes sense. Other church icons, some of which have replaced older icons, could be: the overhead projector (replacing the hymn book); the guitar (replacing the organ); and the closed-eyes, weaving-body, hands-raised worshipers (replacing a quiet and more-âreverentialâ posture). Note: Iâm not critiquing any of these, old or new. Changes may be inevitable.

Where you do find art displayed in Protestant churches, itâs often a grab-bag of popular images like the âpraying handsâ you mentioned, or Richard Hookâs Jesus pictures, or the bearded gentleman praying at a table set with a cup and a loaf of bread, or more recently, Thomas Kinkadeâs work. Our pastors may not wear vestments, but they have their dark suits and power ties (or chinos and polo shirts). Weâve got lecterns, and banners, and, still, some stained glass windows.

And this is where, as Texans may say, many of our readers will be fixinâ to complain.

Why? Because too often, pastors or church decorators will merely sprinkle in such art as afterthoughts. This isnât a criticism, merely an observation, and it applies mainly to the stuff that goes on walls, because by contrast, vestments and stained-glass windows are expected, and the lectern necessary. Yet for the praying-hands paintings or framed prints of a Thomas Kinkade work, theyâre mainly there to fill space. Very likely a pastor, elder, deacon, whomever, feels no need to ask deeper questions about a work of art and how its presence in a church building will honor God. Perhaps also, that is not their job.

All these are likely limited to church services. But icons certainly are not. We find them on TV â negative stereotypes, such as bumbling sitcom dads â and in many stories â positive archetypes, such as fantasy heroes who sacrifice themselves. And as you noted, Scripture itself serves as an icon, by the image of the open book, and by revealing Christ.

Icons in artworks

This brings me to a brief analysis of Thomas Kinkade, fleshing out a modern example of how icons are not bad, only abused. Kinkade paintings, and some fans, may reveal this.

At left: Thomas Kinkade, 1998 (like his older works). At right: Kinkade rebooted, 2004.

First, take a look at this. Itâs not just at another artsy criticism of Kinkade as some sell-out (which may be an unfair personal attack anyway, especially after he has just died). Itâs also not another emotional defense of his works. Rather, itâs a comparison, between Kinkadeâs earlier artworks and his more-popular, light-drenched, firm-lined images.

I am no art critic. But I begin to see why people fault Kinkadeâs later works. Once I had thought those critics merely wanted âgritty,â âreal-worldâ stuff, and disliked visual representations of an ideal. I now see, though, that the better critics fault Kinkade not for imagining the perfect world of the future, when sin and death are over and Christ reigns, but for imagining and imaging a nonexistent âuniverse.â In the Kinkade-verse, serious sin never existed. Not only do you not have to worry about it now, you never did. Iâm not sure how that provides true comfort, and reflections of Godâs grace, to viewers.

This is because in the real world, you need to get through sin before being perfect.

However, I also suggest itâs not wrong to enjoy Kinkadeâs paintings. They are what they are: iconic. One can quibble whether these icon are helpful. But to blast them simply for being iconic, for not including my favorite topic or for not exactly representing a real-world Cottage By the Seashore, would be silly, even legalistic.

Not knowing much about Kinkadeâs career, and not wanting to make this about a person, I can still suggest this: Kinkade should not be blamed for these kinds of images. Rather, we should ask: why do people clamor for them? What do they see reflected that might actually result from legitimate desires? How might those desires be misdirected or endorsed by the wrong kinds of iconic visual art? How can we repair that corruption?

Stories: from characters to icons

The answer may be the same as the reason why weâre writing a series about a broader art-related topic on Speculative Faith, with its emphasis on Christian visionary fiction:

Epic stories glorify our Author by showing the growth of characters into âicons.â

You said this here:

I think this is a central issue of this series, the fact that when we tap into the strongest, most universal icons in our fiction, we create a powerful resonance in the mind of the reader. Very little âtellingâ is necessary. You see the image in your mind, and you know. âThereâs truth here, and somewhere deep within me, I recognize it.â The truer the archetype, I think, the stronger the reaction, which leads directly to your point about Jesus as the ultimate icon.

This may be why people are put off by Kinkade paintings, or novels that have clichĂ©d characters. To them, theyâre not âjust entertainmentâ or âjust pretty.â Instead they see storytelling and beauty as only means to recognizing that greatest truth: the ultimate Author/Artist, Jesus Christ, the only true combination of Character and Icon.

That leads to my suggestion for defining a character, as opposed to an icon. You said:

I might suggest that the difference between a âcharacterâ and an âicon,â in the literary sense, is more an issue of scope than physicality. A character seems to me to be more of a specific case that may incorporate elements of an icon, or several icons. It conveys truth, but not its fullness. If Jesus is an icon, we, his servants and disciples, are characters that in turn reflect His perfect image, as yet imperfectly.

Thus, as Jesus images or âiconsâ (verb) the Father, so we image or âiconâ Jesus â or so we should, and so someday we will! If thatâs true, then, characters in a novel are images of us. In this they are one more degree removed from Christ, but still, they help:

A character is a human figure, shown, described and/or followed in an artwork, song, movie, play, or novel. Unlike icons, a character is not ideal. He or she is âreal world,â with all the limitations, likely even sins, that we would expect.

What do you think?

I agree that the difference between characters and icons is not one of physicality, but of scope. A character is trying to be an icon, an image of the Greater, but hasnât yet arrived. This leads to a storyâs plot. Heroes (and even villains) have not yet achieved their goals.

Thus, a novel that has little to no plot, but presents fake characters that have not yet really gone through this process (e.g., the Perfect Wife or Husband) strikes us as absurd.

Icons are for ideals, and the Ideal God. Not for us. Not for characters who âimageâ us.

If Christ Himself, the exact image of the Father Who never sinned, had to go through a long, arduous process to achieve His goal, why not us? And why not also characters in a story, who âimageâ us as we image Christ? They must also pass from characters to icons.

That seems to reflect the truth of the resurrection. As âcharactersâ now, we are far less than ideal. We sin. We die. Yet Christ has begun changing us from the inside. We already had Godâs Image about us; now itâs begun to be fully restored from within, thanks to the Spirit Who regenerated our spirits. Next comes our bodies. In the future, they will be resurrected, just as our spirits are resurrected now (Romans 8). So will creation.

Will we then only be boring icons? Like the dull sitcom dad who never learns? Like a flat image of frowning Jesus? Like the painting of an idealized and cottage-intensive world?

I donât think so. As resurrected human beings, we will have that process behind us. What a great conversation-starter! With that life story, âiconicâ life could never be boring, and certainly not when we could have never become âiconsâ of Christ without having been characters first. We already see this in stories. Itâs not difficult to imagine about real life.

That might have gone overlong. But itâs an in-depth topic to explore! What do you think about exploring specific examples, by name, in our next two columns â one apiece â with the help of readers, before we likely wrap up by part 6?

Over the past months, I have begun speculating either that my perception is limited or magnified, or that Christian-speculative-fiction blogs are overly focused on writers.

Over the past months, I have begun speculating either that my perception is limited or magnified, or that Christian-speculative-fiction blogs are overly focused on writers.

Why are Fred Warren and I still

Why are Fred Warren and I still

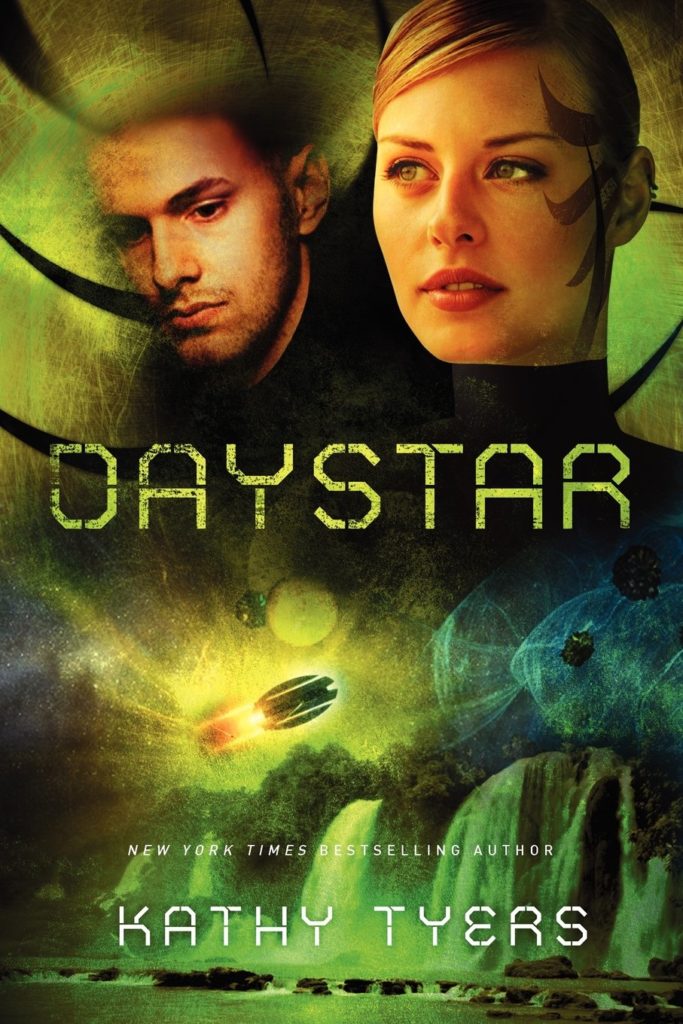

In this alternate universe, when Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary, she focuses on the shame that her pregnancy could bring upon her loved ones, and she declines the honor. The same Lord who let Adam and Eve rebel also allows Mary this choice. (Human freedom as the greatest gift after life itself is a major theme in Daystar.) Her decision utterly changes human history. Within a year, an Earth-orbit-crossing asteroid that would have bounced harmlessly but dramatically off Earthâs atmosphere (with angelic help), guiding the magi to Bethlehem, slams into the Mediterranean instead. Civilization barely survives. The human race develops technology without Christianity. We despoil Earth and leap to the stars in a great wave of space colonization. The Davidic family survives simply because Godâs promises will not be broken.

In this alternate universe, when Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary, she focuses on the shame that her pregnancy could bring upon her loved ones, and she declines the honor. The same Lord who let Adam and Eve rebel also allows Mary this choice. (Human freedom as the greatest gift after life itself is a major theme in Daystar.) Her decision utterly changes human history. Within a year, an Earth-orbit-crossing asteroid that would have bounced harmlessly but dramatically off Earthâs atmosphere (with angelic help), guiding the magi to Bethlehem, slams into the Mediterranean instead. Civilization barely survives. The human race develops technology without Christianity. We despoil Earth and leap to the stars in a great wave of space colonization. The Davidic family survives simply because Godâs promises will not be broken.