Film Failures, Countering Cultures, and Storyâs Power

Something was wrong with me. I knew that when The Gospel Coalition published three columns last week, with differing perspectives on Christian movies, and I found I agreed with all of them. If you have time, I encourage you to read them all, and not only because one is by author, screenwriter, and Speculative Faith contributor Brian Godawa:

- Don’t Discard the Drama for Words by Brian Godawa

- Create Culture, Not Subculture by Mike Cosper

- Unsolicited Advice from a Failed Filmmaker by Joe Carter

TGC introduced the topic:

TGC introduced the topic:

Reflecting on the movies produced by Sherwood Baptist Church, Andy Crouch imagined the scenario where “one or two Christian kids with real talent somewhere in this vast land are going to see these movies, get the sacred-secular dichotomy knocked out of them at an early age, move to Los Angeles, work their tails off, dream, fail, and try again . . . and one day make truly great movies.” What would these movies look like? What advice would you give to a Christian screenwriter, director, or producer who wants to make a film with artistic excellence from a Christian worldview?

Godawa and Cosper seem to agree on what makes great God-honoring stories. But Carter is also right to remind us that the word âChristianâ shouldnât be so scary and that Christians can make âovertâ stories. And yet at the same time, thereâs more to be said âŚ

I wonât say it all. Iâll only present quotes from each, some thoughts, then ask for your views. That may help to prevent a common trope in this story: people talking past each other.

First, from Carter:

Unfortunately, many Christians have convinced themselves that we can approach our vocations with a sense of religious neutrality. But we can’t. Our work either betrays a worldview shaped by Christ or one influenced by the world (or, more likely, a syncretistic mix of the two). [âŚ] This is especially true for those whose vocation entails storytelling. We either consciously acknowledge the ways our faith forms our artistic vocations, or we will be willfully blind to how our sinful nature shapes our craft.

My thought: Neither of the other two writers advocated story âneutrality.â Iâm sure some do, but their reasons would be founded in poor understanding of storyâs purpose.

My thought: Neither of the other two writers advocated story âneutrality.â Iâm sure some do, but their reasons would be founded in poor understanding of storyâs purpose.

Carter would likely agree with Godawaâs advice:

Incarnate your worldview in the structure of the story, not into speeches from the characters. Let the dramatic choices, not verbal pronouncements, carry your message. Drama shows us the results of a lived-out worldview. Showing the consequences of human choices will be more powerful than a preached lecture or sermon of what I should or shouldn’t do.

Thatâs a far cry from âneutrality,â or a false dichotomy that pits Scripture against story.

But Cosper then asks:

In the arts generally, there’s an assumption that the Christian artist’s worldview should result in overtly “Christian” content, where in other vocations, we rarely make the same requirement. [âŚ] We would not expect an engineer to work an ichthus into each of his designs, but (metaphorically speaking) we expect exactly that out of Christian artists, filmmakers, and musicians.

My thought: Very true. Christians need to advocate vocational ministry. And yet âŚ

- Donât Christian artists have the freedom to be as âovertâ or âsubtleâ as they like?

- Isnât the worst problem with some Christian movies not that theyâre showing faith in action, but that theyâre poorly showing it â with tacked-on sermons and over-explaining of emotions that donât reflect how Christians, and humans, truly live?

- Canât an engineer overtly glorify God, or work an ichthus into his designs, especially if he has chosen in his Christian freedom to build mainly for the Church?

Godawa begins to share why we donât need sermons tacked on to stories:

I know, I know, all Christian artists think they value both the craft and the content. But in my experience, they often fool themselves. When it comes time to make a decision for the story or the “message,” they will go with the message every time. Why? Because they feel obligated by God to communicate a clear “message,” or else they have wasted their time. They do not realize that the story itself, along with its style and craft, is part of the message.

My thought: Amen. First, Christians must determine the purpose of a story. Thatâs been the goal of this ongoing series (part 4 releases tomorrow). It questions common Christian justifications for stories, and advocates one single reason:

Storyâs chief end is to glorify God and help us enjoy Him forever.

The very institution of Story glorifies God; it needs no added sermons or explanations. So to honor God, stories donât need to offer explicit Biblical connections. But some certainly can.

Carter suggests:

While not all films made by a Christian need to be explicitly Christian, our culture could use more works that are distinctly Christian. If Christians filmmaker won’t make them, who will?

My thought: Amen. If we truly believe that all good stories reflect the Story, thanks to Godâs common grace, then those positions may be filled. But who will share distinctly Christian stories that sing about themes that common-grace âsecularâ stories can only whisper?

But it seems Carter misses the intent of those who avoid the âChristianâ label:

We Christians are not only set free from our sins but also set free to help carry out God’s redemptive role in creation. In response, we should desire to use our gifts for the glory of God, rather than merely for the advancement of our own exaltation. Why then would we not want our art to be labeled as “Christian”? And why would we Christians want to produce art that cannot be distinguished from those who despise our Redeemer?

My thought: Hereâs why â because that label has been used to excuse poor storytelling. Christians legitimately wince for the same reason that the owner of a good chain-franchise restaurant is embarrassed by another horribly run restaurant of the same chain. Itâs not the chainâs problem, the labelâs problem, or the ownerâs problem. Still the good owner suffers.

As Cosper explained in his response to Carter:

To eschew the âChristianâ label for your films or (your work as an artist generally) is often not rooted in a denial of faith or a denial that faith impacts your work. In the case of most vocational Christian artists that I know, they resist the label because they donât want their work sidelined into the Christian subcultural ghetto.

Do we fear the evil âChristianâ label just as others have feared the evil culture?

My thought: Still, why give up the âChristianâ label so easily? Can Christian storytellers not mount a passionate yet gracious assault on poorly told âChristianâ stories and re-take the title? I refuse to give it up, just as I refuse to give up the perfectly good and historical name âChristianâ to apply to believers in Jesus, in favor of some cumbersome term like âChrist-follower,â which is also itself doomed to co-opting by hypocrites.

Letâs quit being so fearful of the âChristianâ term being hijacked. This practice is itself a symptom of culture-reactionary thinking! If we truly want to create culture instead of âcounter-culture,â weâll refuse to reject good things â such as the âChristianâ label.

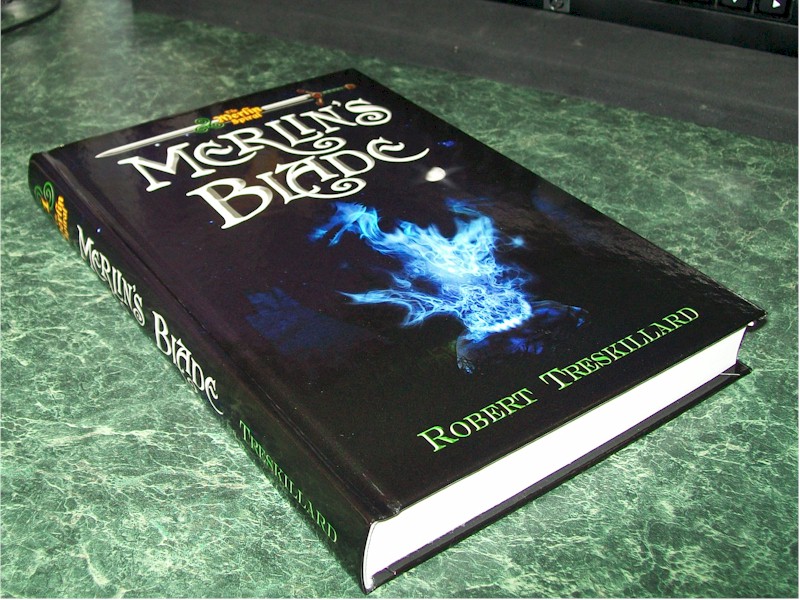

Its book cover.

Its book cover.

Many Christians defend their fiction enjoyment by saying âitâs not sinfulâ or âit reminds me of the Bible.â But

Many Christians defend their fiction enjoyment by saying âitâs not sinfulâ or âit reminds me of the Bible.â But

It was while thinking about miracles, and particularly Jesusâ statement that all it takes to move a mountain is faith the size of a mustard seed, that I got a glimmer of the idea that turned into my first Christy Award-winning novel, River Rising. The question I asked myself was, âWhat would daily life look like for someone with that kind of faith?â

It was while thinking about miracles, and particularly Jesusâ statement that all it takes to move a mountain is faith the size of a mustard seed, that I got a glimmer of the idea that turned into my first Christy Award-winning novel, River Rising. The question I asked myself was, âWhat would daily life look like for someone with that kind of faith?â Athol Dickson is a novelist, teacher, and independent publisher. His novels transcend description with a literary style that blends magical realism, suspense, and a strong sense of spirituality. Critics have favorably compared his work to such diverse authors as Octavia Butler (Publisher’s Weekly), Hermann Hesse (The New York Journal of Books) and Flannery O’Connor (The New York Times). One of his novels,

Athol Dickson is a novelist, teacher, and independent publisher. His novels transcend description with a literary style that blends magical realism, suspense, and a strong sense of spirituality. Critics have favorably compared his work to such diverse authors as Octavia Butler (Publisher’s Weekly), Hermann Hesse (The New York Journal of Books) and Flannery O’Connor (The New York Times). One of his novels,

Christians are saved for a mission. Itâs summarized by Jesusâs Great Commission (Matt. 28: 16-20). He said to go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing and teaching them. We work to spread the Gospel, organize churches, support our families, and more. Given all of those clearly defined parts of our mission, why spend time reading or defending fiction?

Christians are saved for a mission. Itâs summarized by Jesusâs Great Commission (Matt. 28: 16-20). He said to go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing and teaching them. We work to spread the Gospel, organize churches, support our families, and more. Given all of those clearly defined parts of our mission, why spend time reading or defending fiction?