Define âChristian Speculative Storyâ

What is this thing called Christian speculative fiction?

Readers and writers are still debating those definitions, and I think thatâs okay.

The most recent  instance was Monday at this site, in the comments here. Rebecca Miller admitted her original question was more broad, about which Christian speculative stories â besides Lewis and Tolkien â would be considered required reading. Still, some of the submissions were from a wider field of reading than what most would consider âChristian.â

To prove that, we must define Christian speculative fiction/stories. How do you define that?

Hereâs a possible pattern for discussion:

- Write a short definition of Christian speculative fiction/stories.

- If you like, break down the words and phrases with sub-definitions.

- Any bonus comments, with evidence or preemptive rebuttals of criticisms.

Hereâs what I mean.

1. Definition of Christian speculative stories.

Hereâs my working definition for discussion/revision.

Christian speculative stories are fantastic tales that are written, or otherwise shown, clearly yet naturally from a Christian worldview. That is, the hero and plot reflects Christ and the Gospel, the characters reflect real people, and the story-world and style reflect reality and God’s truth, wonders, and creativity.

2. Phrase breakdown.

Christian speculative stories are fantastic tales

- Weâre speaking here of story-worlds including things we donât normally see: fantasy, technology, creatures, alternate histories, miracles, and so on.

that are written, or otherwise shown,

- These include novels, television, plays, motion pictures, and so on.

clearly yet naturally from a Christian worldview.

- What this means: the hero/plot, characters, and world run on Biblical ârulesâ â not necessarily Godâs âwill of commandâ or revealed will, but His sovereign will (e.g., sin brings consequences, we donât always have answers this side of Heaven, He is God).

- What this doesnât mean: every character finds God or finds answers to every question.

- What this means: the author is knowingly telling the story according to Biblical ârules.â

- What this doesnât mean: the author is clearly a professing Christian (but Iâm not aware of a case in which a non-Christian author wanted to write a specifically Christian story).

That is, the hero and plot reflects Christ and the Gospel,

-

"The Avengers" has a basically Christian worldview, true heroism, and self-sacrifice. But is it a "Christian story"?

What this means: the hero in some sense is a Christ-figure, and sin and grace are seen.

- What this doesnât mean: any hero, even if he sacrifices himself, counts as a Christ-figure.

- Example: the alternate gospel âstoryâ of Mormonism, a fantastic tale with other planets and everything, is not the original Gospel. This goes beyond intra-Church debates over baptism or âCalvinismâ vs. âArminianism,â for the Mormon concept of Jesus and His mission, the Gospel, is skewed to the point of being a false âJesusâ and false âgospelâ (Galatians 1: 6-9). For more, see here.

the characters reflect real people,

- As in reality, characters behave like actual humans, not one-dimensional clichés. They show the Biblical truth that man is sinful, yet can be redeemed, and that even sinful people can do good, even if they have bad motives (Matt. 7:11).

and the story-world and style reflect reality and God’s truth, wonders, and creativity.

- What this means: in such a story, God is âseen,â even if He seems hidden. Heâs shown in a way that nature itself reveals Him. âHis invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made. So they are without excuse.â (Romans 1:20)

- What this doesnât mean: God and His nature are seen just as clearly as He is revealed in the Bible. Scripture is final, only-certain revelation from God Himself. So no speculative novel need also try to act like the final, most-comprehensive word on the subject.

- What this means: the story includes truth, not always accessible or resolved or seen, but always present â even behind the scenes, even just out of reach.

- What this does not mean: beauty in style and craft donât matter if the story has truth.Truth without beauty is a lie. Beauty without truth is ugliness.

3. Bonus: why read newer Christian speculative stories?

Becky later asked this question:

Iâm beginning to wonderâwe have a lot of writers who stop by, and readers who read general speculative fiction, but do we also have visitors who read âChristian speculative fictionââthe books we have here in the Spec Faith library, the books many of our guest bloggers write?

Iâve also begun to wonder if Christian readers are reading anything besides classic fantasy â works by Lewis, Tolkien, MacDonald, etc. â and secular speculative novels. Recently I had to razz a friend from church who was only recently pushed into reading The Hunger Games. His reason: it wasnât Lewis or Tolkien, so why read anything else?

Iâd rephrase his question, and not only because this brother happens to lead the singing at my church: it isnât by Isaac Watts or Charles Wesley, so why sing any other song?

Rather, God should be worshiped with âa new song,â played excellently (Psalm 33:3).

And if worship is more than singing, and it is, we must also enjoy new stories for His glory.

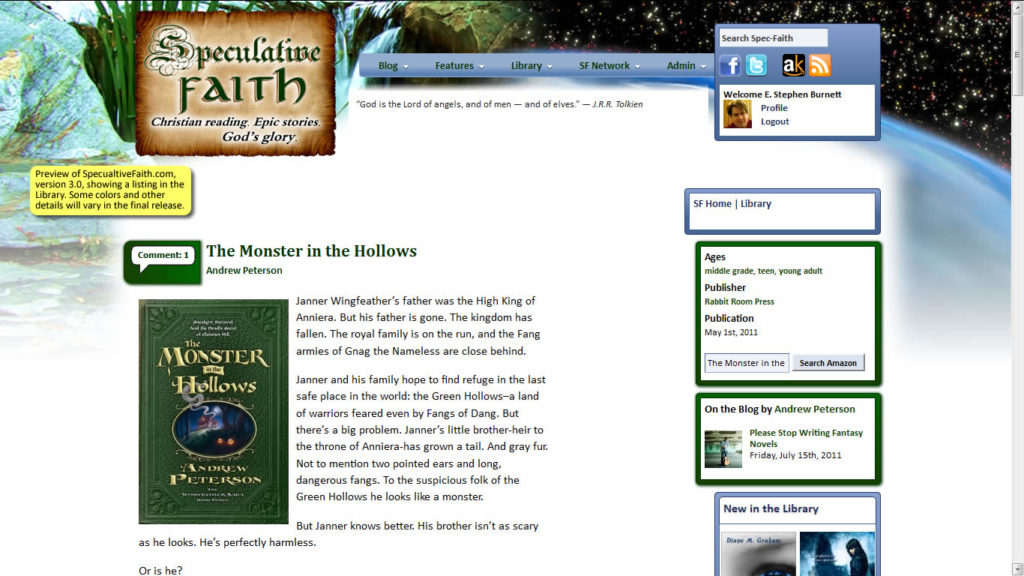

Browse our Library shelves. On June 1, weâll launch an upgraded Speculative Faith, with new cross-reference options, organization, and featured reviews. Itâs the best way we know to find new authors and novels, similar titles, and fantastically unique means of worshiping God â not only with classic fantasy or secular books, but with Christian speculative stories.

Shannon Dittemore has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and a focus on youth and young adult ministry. The daughter of one preacher and the wife of another, she spends her days imagining things unseen and chasing her two children around their home in Northern California. Angel Eyes is her first novel.

Shannon Dittemore has an overactive imagination and a passion for truth. Her lifelong journey to combine the two is responsible for a stint at Portland Bible College, performances with local theater companies, and a focus on youth and young adult ministry. The daughter of one preacher and the wife of another, she spends her days imagining things unseen and chasing her two children around their home in Northern California. Angel Eyes is her first novel.

People, perhaps moviemakers themselves, were trying to do some mad science in the middle of Spielberg-esque, or perhaps Roland Emmerich-esque, Big-City America. Their reasoning was this: if colliding weather fronts during severe storms can spawn tornadoes, why not come up with some way to combat them by generating our own weather fronts of hot or cold air? So they did. (I think my brain filled this in, as behind-the-scenes.) Naturally, things began to go awry. Instead of fighting against naturally spawned funnel clouds, whatever technologies these mad scientists had developed â ironically â themselves spawned the tornadoes.

People, perhaps moviemakers themselves, were trying to do some mad science in the middle of Spielberg-esque, or perhaps Roland Emmerich-esque, Big-City America. Their reasoning was this: if colliding weather fronts during severe storms can spawn tornadoes, why not come up with some way to combat them by generating our own weather fronts of hot or cold air? So they did. (I think my brain filled this in, as behind-the-scenes.) Naturally, things began to go awry. Instead of fighting against naturally spawned funnel clouds, whatever technologies these mad scientists had developed â ironically â themselves spawned the tornadoes.

But when I asked, Whedon was reluctant. He only wanted to hang out and chat, no interviews. So after each of my repeated requests, he ignored me and simply continued talking to himself â all the time with his best attempt at snappy clever dialogue â while holding up his hands to imagine and block out his next series of shots.

But when I asked, Whedon was reluctant. He only wanted to hang out and chat, no interviews. So after each of my repeated requests, he ignored me and simply continued talking to himself â all the time with his best attempt at snappy clever dialogue â while holding up his hands to imagine and block out his next series of shots. Morgan Freeman, the Stately Courageous President! He was there (along with another guy who looked like him?), holding up his hands, and kindly reassuring the world that all was not lost. We will rebuild, he intoned. The human spirit cannot be vanquished. And so hope will arise from the ashes.

Morgan Freeman, the Stately Courageous President! He was there (along with another guy who looked like him?), holding up his hands, and kindly reassuring the world that all was not lost. We will rebuild, he intoned. The human spirit cannot be vanquished. And so hope will arise from the ashes.

Last week

Last week

Letâs face it, the digital book age is here and it is here to stay. Yes, thereâs something awesome about having a real book in your hands. Yes, they probably will never go away. But they will diminish. They will eventually become the minority of the book industry. (Wait, I think they may already have. Must check the facts.) And as the digital book age progresses, the technology will also progress.

Letâs face it, the digital book age is here and it is here to stay. Yes, thereâs something awesome about having a real book in your hands. Yes, they probably will never go away. But they will diminish. They will eventually become the minority of the book industry. (Wait, I think they may already have. Must check the facts.) And as the digital book age progresses, the technology will also progress. Keven Newsome is a graduate student at the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, where he is pursuing a Master of Arts in Theology specializing in Supernatural Theology. He writes stories that portray the Supernatural and Paranormal with an accurate Biblical perspective. He is the author of Winter, a thriller published by Splashdown Darkwater. He currently lives in New Orleans, LA with his wife and their two children.

Keven Newsome is a graduate student at the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, where he is pursuing a Master of Arts in Theology specializing in Supernatural Theology. He writes stories that portray the Supernatural and Paranormal with an accurate Biblical perspective. He is the author of Winter, a thriller published by Splashdown Darkwater. He currently lives in New Orleans, LA with his wife and their two children.

My mission is not to deny all those reasons for enjoying stories, but to suggest that they result from what I term the chief end of Story. This is based on what the Westminster Shorter Confession says is âmanâs chief end,â as

My mission is not to deny all those reasons for enjoying stories, but to suggest that they result from what I term the chief end of Story. This is based on what the Westminster Shorter Confession says is âmanâs chief end,â as

Just as any kind of house, no matter how âpostmodernâ its outside architecture, is built on a foundation of physical laws, so any good story, no matter how âpostmodern,â is built on the basis of the Christian worldview.

Just as any kind of house, no matter how âpostmodernâ its outside architecture, is built on a foundation of physical laws, so any good story, no matter how âpostmodern,â is built on the basis of the Christian worldview.