Rearranging Icons 5: In The Eye Of The Beholder

(Once again, my remarks in blue, Stephen’s in black)

Stephen,

Response to your last installment. Sorry I didn’t get this to you earlier–busy week at work.

Though this series has brought some varying views, so far we have not disagreed on anything. It seems most readers, too recognize that icons — i.e., symbolic or graphical representation of a larger series of truths or ideals — are inevitable in our lives. Whether we look at the history of the Church, modern-day stories, or the Bible itself, we can’t help finding those simple, recognizable icons that are “implanted” in our minds.

No disagreement, eh? Okay, fight’s on, my friend. 🙂

I think it’s more elegance (expressing a complicated idea concisely) than simplicity, because icons are complex. They distill ideas, information, and emotions into a compact package that can be understood intuitively. If you tried to explain all of that in a speech or essay, it might take hours and dozens of pages.

And it would seem those who are not aware of how this concept works may likely be taken advantage of, by storytellers, artists, and even ad-makers.

It’s an efficient means of communication, and speaks directly to the subconscious. People can and will use those qualities to suit their own agendas, but I’m more interested in the idea that readers can have a richer reading experience and writers can tell richer, deeper stories if they understand how this works.

Your discussion turns to art at this point…

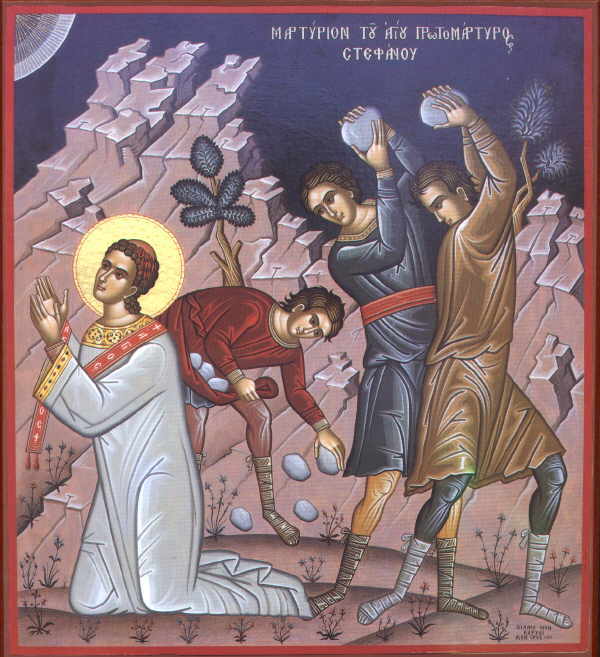

This is by no means unknown to the (Protestant Evangelical) Christian world. We may not have necklaces with Masonic symbols (not sure what you’re referencing here), or simple-lined, flat-colored artwork, like the representations of Jesus Christ that you have included in part 1 and part 3 of this series. But we do have icons.

Yes, but more often than not, we’ve forgotten what they mean. On some level, the icon still communicates, but that communication is hindered when it’s taken out of context. It’s like slapping a facsimile of the Mona Lisa on a bumper sticker. More powerful is the iconography of our architecture. Our churches don’t resemble temples so much as lecture halls or convention centers. Big, white boxes with lots of chairs and a premium audiovisual system. Instead of cathedrals, we have “campuses.”

This brings me to a brief analysis of Thomas Kinkade, fleshing out a modern example of how icons are not bad, only abused. Kinkade paintings, and some fans, may reveal this.

I now see, though, that the better critics fault Kinkade not for imagining the perfect world of the future, when sin and death are over and Christ reigns, but for imagining and imaging a nonexistent “universe.” In the Kinkade-verse, serious sin never existed. Not only do you not have to worry about it now, you never did. I’m not sure how that provides true comfort, and reflections of God’s grace, to viewers.

I’m not buying your premise here. I don’t think Kinkade’s work has anything to do with sin, and I highly doubt he was consciously trying to image a perfect, sinless universe. He painted pretty pictures of pleasant scenes that elicited a restful state of mind. He liked to play around with light on a 2D canvas, and he found a formula that was attractive and appealing—and sold his paintings. I don’t think it’s much more complex than that. Nice pictures for nice Christians. Where it falls down as art, I think, is that it doesn’t communicate much beyond the nice. Art surprises, challenges, even confuses at times. It’s meant to show us the world through new eyes and reveal things we haven’t noticed before by virtue of its creative perspective. A picture can be pretty and enjoyable (or ugly and shocking) without being particularly artistic or meaningful, but its utility, audience, and lifespan are limited.

This may be why people are put off by Kinkade paintings, or novels that have clichéd characters. To them, they’re not “just entertainment” or “just pretty.” Instead they see storytelling and beauty as only means to recognizing that greatest truth: the ultimate Author/Artist, Jesus Christ, the only true combination of Character and Icon.

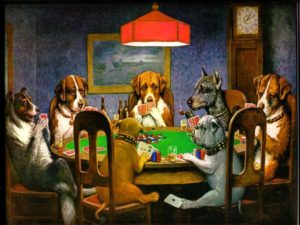

Maybe, but I think it’s probably more about being hacked off that the kids are having chocolate cake for breakfast instead of something more nutritious. Our sense of aesthetic justice is offended. VanGogh dies penniless, but people pay thousands of dollars to create their own private Kinkade galleries, or worse, cover their walls with Velvet Elvis or Dogs Playing Poker. It’s just not fair. Sometimes beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and that perception, to the chagrin of artists and authors across time, is often unfathomable.

Back to stories now…

Epic stories glorify our Author by showing the growth of characters into “icons.”

They can, but there aren’t many examples of characters, as compared to the total population, who actually manage this. And that’s okay. The community of characters we can rightly call icons in the truest sense of the word should be an elite group. In the less-than-immortal words of Syndrome, “When everybody’s super, nobody will be.” Trying to make our characters icons will be an exercise in futility for most of us, and probably not nearly as helpful as depicting characters who are fighting to become better people, and failing nearly as often as they succeed. The icon is a point of reference, a target, a bar set a few inches above our personal best. So, as you said…

A character is a human figure, shown, described and/or followed in an artwork, song, movie, play, or novel. Unlike icons, a character is not ideal. He or she is “real world,” with all the limitations, likely even sins, that we would expect.

Fair enough, but I don’t quite agree with this:

A character is trying to be an icon, an image of the Greater, but hasn’t yet arrived. This leads to a story’s plot. Heroes (and even villains) have not yet achieved their goals.

From the character’s point-of-view, I don’t see this happening very often. Characters are mostly trying to just live their life, or survive to see another sunrise. Their personal growth is something they don’t realize until near the end of their story, though that journey is visible to the reader and part of what keeps us engaged.

Thus, a novel that has little to no plot, but presents fake characters that have not yet really gone through this process (e.g., the Perfect Wife or Husband) strikes us as absurd.

Yes, populating a story with Barbie and Ken dolls isn’t very interesting, and certainly not realistic.

Icons are for ideals, and the Ideal God. Not for us. Not for characters who “image” us.

Okay, this begins to touch on something important, I think. In one sense, you’re right—we can’t make ourselves perfect images of God, nor can we fashion “iconic” characters through the force of our own talent and will. Human beings become conformed to the image of God through His power and grace and our cooperation with His work in our lives. We’ve already discussed how all Christians serve as icons of Christ, even imperfectly. Some progress farther on the journey than others in this life. A few may serve as models and exemplars, heroes and heroines of the faith for those of us who follow, long after their death.

But there’s also another dimension for characters in a story: the audience gets a vote. Characters don’t land on the bookshelf as freshly-minted icons on the day of publication. Millions of readers, over years, and even centuries, make that decision in consensus. Odysseus, Romeo and Juliet, Oliver Twist, Aslan, Frodo…we can all rattle off a list of famous literary characters that few would dispute are iconic, but they all started out as characters in a story no one but the author had seen. When people read the stories, these characters spoke to something profound and enduring within them. People talked about the stories and the characters, and shared them with their friends. Over time, the characters grew in stature and significance as they touched more and more lives. Just hearing their names is enough to trigger a flood of thoughts and emotions.

That might have gone overlong. But it’s an in-depth topic to explore! What do you think about exploring specific examples, by name, in our next two columns — one apiece — with the help of readers, before we likely wrap up by part 6?

Sounds good, though I think I’m going to post this as part 5, then maybe you can follow with your specific example and I’ll finish with mine.

Best Wishes,

Fred

Our churches don’t resemble temples so much as lecture halls or convention centers. Big, white boxes with lots of chairs and a premium audiovisual system. Instead of cathedrals, we have “campuses.”

I’ve been having that exact thought ever since returning from a spring break trip to London. Having seen Westminster Abbey, St George’s Cathedral in Windsor–even the small Holy Trinity Church in Oxford, where C.S. Lewis is buried–modern churches seem so much less. To quote my essay I wrote for a class:

I think back to the churches I’ve regularly attended (….) Three churches from three denominations in three separate states, but the building have a certain sameness, like Old Country Buffet or Pizza Hut; different layouts, same content. After all, we worship the same God–why confuse people by making his houses different?

Of course, if a cathedral was built today, people would (rightly?) decry the huge expense as self-glorification instead of caring for the poor. But our God is a god of beauty and wonder–why are his houses so ugly?

Wow, that’s a trip I’d love to take some day.

There are plenty of practical considerations that factor into the construction of any given church building, and, of course, what actually goes on inside (and outside) the building is far more important than the niceties of its design.

I’m not advocating a return to medieval European architecture, though a lot of it is awe-inspiring and I think there are some things we could re-learn from it about blending beauty, function, and symbolism. My point here is to provide an example of yet another icon that delivers an unspoken message about how we approach God and what is important to us, an icon that could stand a little more prayerful thought and consideration.

It’s easy to say, “The Church is people, not a building,” and forget that the places we build to gather the Church tell a story of their own, both to us and to the outside world. Have we built to encourage an atmosphere of worship, or to facilitate something else? Does our worship space inspire us to take out our pencils, start a mosh pit, order a cappuchino, or fall on our knees? I think that’s a question worth asking. The answers will vary.

Just about anything churches spend money on will at some time be played against the poor, as if it’s an either-or proposition: Build a church, or help the poor. Pay the pastor, or help the poor. Run the furnace, or help the poor. It’s a false dilemma. As to cost, I don’t think it costs any more to exercise additional care in this area and add a little meaningful beauty than to ignore it, and both poor and rich benefit.

And that’s about how I feel on that subject.

And, as you said, characters aren’t necessarily good, which means when they become an icon, said icon is not necessarily suggesting anything positive. I don’t consider Odysseus, Romeo & Juliet, Han Solo, Rhett Butler, or Indiana Jones especially positive.

I don’t know about “rightly.” I think motives can be pure even when decorating the house. Oddly, a friend and I were talking about that on Sunday, discussing how we’re both a bit mixed emotionally when it comes to coffee shops and bookstores in church. She said, really, in the end, her primary hesitation is when she sees business meetings clearly going on 15 minutes before service starts.

One thing, really quick:

Fred, you’re a storm trooper. I absolutely loved the breakdown you did of art in the eye of the beholder. Great stuff.

[…] likely wrap up this series next week. Here, I’ll reply to Fred’s Tuesday column, with his comments indented. It seems like we’re closing in on a Grand Theory of Fiction […]