Fantasy: An Indispensable Way To Understand Ourselves

âThe problem . . . is that whereas adults are readily aware of myths they have outgrown, they are blind to ones that they currently hold to be real.â â Carl Johnson

Like Peter Pan, too many of us enter the âreal worldâ of adulthood and forget how to fly. Our wings are clipped by failing to preserve the imaginative vitality of our childhood. The result is a life that never reaches maturity, for many things about life and ourselves can only be explored through fantasy.

Like Peter Pan, too many of us enter the âreal worldâ of adulthood and forget how to fly. Our wings are clipped by failing to preserve the imaginative vitality of our childhood. The result is a life that never reaches maturity, for many things about life and ourselves can only be explored through fantasy.

Itâs In Our Blood

Fantasy is not merely the result of adults telling children wild stories. In his book, From Two to Five, K. Chukovsky relates a telling story about how the minds of children work. Though it is easy for us to believe that realism is what our children need and that we shouldnât fill their minds with fantasies, the work of scientist E. I. Stanchinskaia tells a different story. From infancy, she kept her son from unrealistic folk tales and fantasies and only read him simple realistic stories taken from the world of reality and nature. She only presented him with things that could be empirically verified.

The Result?

Despite all this, Stanchinskaiaâs son generated his own fantasies. There were imaginary elephants, bears, and friends in his room. The rug he sat on was a ship. He was a reindeer when it snowed, and on and on. Although he had been kept from any hint of fantasy, he acted as though heâd been raised with it. He behaved like any imaginative child would.

Making Reality More Visible

Since fantasy is so embedded in our lives, it is no surprise that by age three, children are able to recognize the difference between an imaginary world and the reality that they live in (Woolley, 1997). After all, the word âfantasy,â which comes from the Classical Greek word âphantasia,â means âto make visible.â Why, then, shouldnât it make our reality more visible, more understandable?

Filling In The In-Between

Fantasy is a result of learning about life through language. Some of our earliest conceptual explorations are with opposites, such as when we find the warm that sits between hot and cold. But what is between life and death or a human and an animal? What we discover in our inventions between these opposites is the stuff of all the fantasy stories and myths in our world, from ghosts to zombies, mermaids to werewolves, elves to talking mice.

Bridging The Gap By Pretending

Fantasy is the outcome of our contemplation on basic life questions: Why and how are we different from other animals? What is death and why? With fantasy, our minds use complex metaphors to bridge the gap across the unknown in order to broaden and inform what we do know.

Fantasy is the outcome of our contemplation on basic life questions: Why and how are we different from other animals? What is death and why? With fantasy, our minds use complex metaphors to bridge the gap across the unknown in order to broaden and inform what we do know.

Thus, when a child pretends he sees or is, he is crucially engaging in understanding himself and his world. Part of his journey of self-discovery involves experiencing different modes of being.

A Fairytale Can Inform Reality

The Scottish philosopher, Alasdair MacIntyre, believed that our lives only make sense to us through the telling of stories. He said that it is through the myths and tales of childhood that we understand how to act in our own dramas and understand our own world.

Essential Help To Navigate A Complex World

The world is more complicated than the pragmatic would have us believe. If it werenât, then why would we need poets, painters, and storytellers? If we believe that empirical knowledge is all our children need to navigate the world, then we are in danger of denying the most important things in the world: the inexpressible things.

The truth is that we need every tool at our disposal to even weakly grasp a meaningful understanding of ourselves and our world. And metaphor—indeed fantasy—is at the top of that list of tools.

– – – – –

Brent King is a freelance writer of Christian fantasy and historical fiction from Lake Oswego, Oregon. His debut novel, The Fiercest Fight, was published in November 2015. Find him on Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Goodreads, and his website.

Brent King is a freelance writer of Christian fantasy and historical fiction from Lake Oswego, Oregon. His debut novel, The Fiercest Fight, was published in November 2015. Find him on Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Goodreads, and his website.

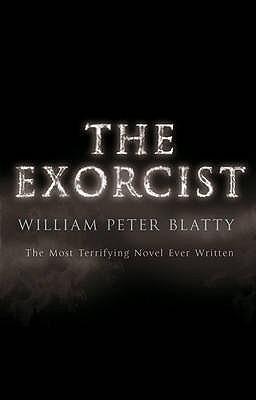

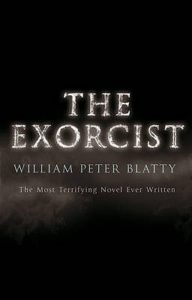

ears ago, I blazed through William Blatty’s The Exorcist. It pretty much blew my mind into a million pieces. I’ve never seen the film and though I already knew the general idea, the book was very nearly a masterpiece.

ears ago, I blazed through William Blatty’s The Exorcist. It pretty much blew my mind into a million pieces. I’ve never seen the film and though I already knew the general idea, the book was very nearly a masterpiece.

Yes, I finally went to see Star Wars: The Force Awakens. I successfully avoided early reviews and spoilers, and as a result, I thoroughly enjoyed the movie experience. Here are my reflections, sanitized to keep away from spoilers so that I don’t ruin the movie for any of you who may not have seen it yet.

Yes, I finally went to see Star Wars: The Force Awakens. I successfully avoided early reviews and spoilers, and as a result, I thoroughly enjoyed the movie experience. Here are my reflections, sanitized to keep away from spoilers so that I don’t ruin the movie for any of you who may not have seen it yet. The main topic came from a discussion I had before I saw the movie. Apparently some Christians were taking a stand against the movie—something I don’t remember from Star Wars number one. Ironically, the friend I was with said her pastor had mentioned it in a recent sermon because of its strong portrayal of good versus evil. In other words, some Christians apparently see the movie as containing questionable elements and some, positive elements.

The main topic came from a discussion I had before I saw the movie. Apparently some Christians were taking a stand against the movie—something I don’t remember from Star Wars number one. Ironically, the friend I was with said her pastor had mentioned it in a recent sermon because of its strong portrayal of good versus evil. In other words, some Christians apparently see the movie as containing questionable elements and some, positive elements. The greatest problem with this understanding is the way it presents life as a duality, as if there are two equal and opposites in the world.

The greatest problem with this understanding is the way it presents life as a duality, as if there are two equal and opposites in the world.

The mist hung from the branches of the ancient trees like threads from a tattered banner, though the last vestiges of sunlight still glimmered on the horizon. Conor Mac Nir shivered atop his horse and tugged his cloak securely around him, then regretted the show of nerves. He had already seen the disdain in the eyes of the king’s men sent to escort him. There was no need to give them reason to doubt his courage as well.

The mist hung from the branches of the ancient trees like threads from a tattered banner, though the last vestiges of sunlight still glimmered on the horizon. Conor Mac Nir shivered atop his horse and tugged his cloak securely around him, then regretted the show of nerves. He had already seen the disdain in the eyes of the king’s men sent to escort him. There was no need to give them reason to doubt his courage as well.

In its main point (to wit: droids are slaves), the article is unconvincing. The assertion that droids are slaves rests on the idea that they are sentient, and the case that they are sentient rests on huge extrapolations from small details. Hence Threepio’s exclamation “Thank the Maker!” is said to prove that droids have their own theology, and Luke’s comment on Artoo’s “devotion” means – why didn’t you think of this? – that droids have free will. Also, the fact that Artoo is told he will “learn respect” means he’s sentient, because otherwise respect “could simply be programmed.”

In its main point (to wit: droids are slaves), the article is unconvincing. The assertion that droids are slaves rests on the idea that they are sentient, and the case that they are sentient rests on huge extrapolations from small details. Hence Threepio’s exclamation “Thank the Maker!” is said to prove that droids have their own theology, and Luke’s comment on Artoo’s “devotion” means – why didn’t you think of this? – that droids have free will. Also, the fact that Artoo is told he will “learn respect” means he’s sentient, because otherwise respect “could simply be programmed.” It is to assume that humanity can create that consciousness in other beings, can in fact create whole races. (Incidentally, this puts a whole new shade of meaning to Threepio’s “Thank the Maker!” Our intrepid author regards this as genuine droid religion – but who is the god of this religion? Because the droids’ maker is Man.)

It is to assume that humanity can create that consciousness in other beings, can in fact create whole races. (Incidentally, this puts a whole new shade of meaning to Threepio’s “Thank the Maker!” Our intrepid author regards this as genuine droid religion – but who is the god of this religion? Because the droids’ maker is Man.)

As the new year gets underway, we often think of January 1 as an opportunity to start afresh. Thus the resolutions: this year I’ll start exercising, this year I’ll get organized, this year I’ll break the habit of procrastinating. It’s admirable to want to better ourselves, to rid ourselves of bad habits, and to start a pattern of healthier, more responsible living.

As the new year gets underway, we often think of January 1 as an opportunity to start afresh. Thus the resolutions: this year I’ll start exercising, this year I’ll get organized, this year I’ll break the habit of procrastinating. It’s admirable to want to better ourselves, to rid ourselves of bad habits, and to start a pattern of healthier, more responsible living.![PowerElementsCharacterDevelopment[1000][1]](http://www.speculativefaith.lorehaven.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/PowerElementsCharacterDevelopment10001-205x300.jpg) By far the greatest number of stories depict characters who exhibit growth. At the beginning the protagonist has a problem or story question that drives her actions forward. But she also has an inner life that dovetails with these outer circumstances. By the end of the story, the character has learned what she needs, made the changes her circumstances require, commits to a new course of action, and thus answers the story problem which confronted her at the beginning.

By far the greatest number of stories depict characters who exhibit growth. At the beginning the protagonist has a problem or story question that drives her actions forward. But she also has an inner life that dovetails with these outer circumstances. By the end of the story, the character has learned what she needs, made the changes her circumstances require, commits to a new course of action, and thus answers the story problem which confronted her at the beginning.

ows the Hardy Boys books (and if you don’t, then you have my pity). Something about those books were very endearing and I gobbled up every single one in my county library system. There is another literary comrade of the Hardy Boys that many people may not know named Tom Swift, Jr. His father, Tom Swift, Sr. was the protagonist of a popular series in the early 20th century, having all sorts of adventures involving his inventions. The second series, centering around his son, was far more high-tech and far-reaching, with Swift, Jr. heading out to space and to the depths of the ocean. Jules Verne would have loved these books.

ows the Hardy Boys books (and if you don’t, then you have my pity). Something about those books were very endearing and I gobbled up every single one in my county library system. There is another literary comrade of the Hardy Boys that many people may not know named Tom Swift, Jr. His father, Tom Swift, Sr. was the protagonist of a popular series in the early 20th century, having all sorts of adventures involving his inventions. The second series, centering around his son, was far more high-tech and far-reaching, with Swift, Jr. heading out to space and to the depths of the ocean. Jules Verne would have loved these books.