The Crossover Bug

According to some, Christian fiction authors are making headway in the general market. Granted, much of it appears to be focused on women’s literature—aka romance—and mystery, but it is happening to some degree.

The above linked article asks the question, “Does the mainstreaming of Christian fiction mean a watered-down faith element?”

Abingdon’s Hoort doesn’t expect either secular or CBA publishers to abandon their core readers, believing it to be a “both and” situation. “There will still be future releases for readers who want a clear Gospel message in their novels alongside books that are clean, fun, and inspiring but not overtly religious.”

This will do little, however, to calm the fears of those Evangelicals that such crossovers do mean a watering down of the faith—for those books. So many still expect a Christian author writing Christian fiction to have a clear Gospel message. Just look at the recent Christian films like “God is Not Dead.” No going for the subtle approach there.

Indeed, the article goes onto say that crossing over into the general market has become easier for Christian authors, in part because such traditional restrictions on Christian fiction have eased up.

Sarah Freese, an agent at Wordserve Literary . . . , “While there are still rules and expectations within the CBA [Christian Booksellers Association], more readers are open to Christian fiction that [doesn’t offer] ‘typical Evangelical’ answers.”

For some Evangelicals, that is code-speak for “it won’t have a strong gospel message.”

And you know, they are probably right in some, if not many cases. The question should be, is that a good or bad thing?

The article, when you boil it down, makes the case that this change is happening for two main reasons. One, the advent of self-publishing, especially in ebooks. Two, the faith-influence of Millennials as they become authors.

As the street-cred of indie authors has risen in the last few years as a viable option to publish and reach readers directly, the more it has stretched the expectations of traditional Christian publishing. Unchained from the Christian bookstore audience’s expectations, these authors are free to explore the Faith and its implications for life in ways previously deemed off-limits. As these authors and books successfully find readers, they force the CBA to take those readers into consideration as they decide on what their publishing schedule will look like into the future.

This includes small presses like Enclave Publishing, formerly Marcher Lord Press. Their success in publishing only Christian science fiction and fantasy titles has forced Christian publishers to rethink the viability of those genres, which have traditionally been weak sells in Christian bookstores. Enclave’s titles, at times, have stretched the expectations of what Christian fiction can do and be.

Meanwhile, current Christians readers, especially of the Evangelical stripe, are often unaware of the history of Christian fiction.

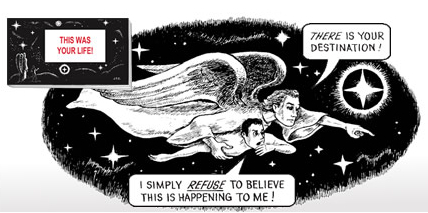

Many don’t know that prior to the 60s and 70s, there wasn’t a Christian fiction market. If you were a Christian and wrote a book involving Christian themes, your only option outside of self-publishing was to get published by a general market publisher. It is why authors like C.S. Lewis and J.R. Tolkien were not published by Christian publishers. There were few, if any, Christian publishers in those days publishing any kind of fiction save gospel tracts like Jack Chick’s—which just may be the forerunner of modern Christian speculative fiction publishing.

As the rise of baby booming Evangelicals influenced the rise of the Christian market, and thus the rise of Christian publishing, so too the influx of Christian Millennials into Christian publishing is bound to change the face of both what Christian fiction looks like and its goals.

These two combined create a synergistic dynamic that shifts Christian fiction back to a more general market style and drives the move toward more Christian authors crossing over into the general market. Incidentally, we’ve seen this same movement happen in Christian music.

Do you think this is a good direction? Why or why not?

I’ve never seen the issue here. I’ve read plenty of stuff in the secular arena that had great Christian messages/thoughts. Gosh, remember the Mitford books? I’m pretty sure they had a secular publisher (Amazon says Penguin Group). The fourth book had the most wonderful picture of a man coming to Christ at Christmas. It remains one of my favorite Christmas stories.

Plenty of believers write for the secular market. But it takes a good writer to articulate Christian beliefs while also giving other points of view a hearing.

I think it’s a positive change. As C.S. Lewis said, “The world does not need more Christian writers–it needs more good writers and composers who are Christian.”

It’s also great when an author can do both (write mainstream AND more overtly Christian books), because their mainstream readers may become more open to picking up one of their “Christian” titles.