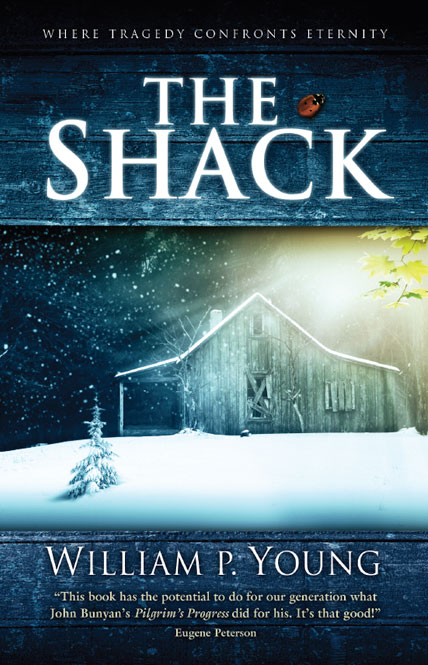

Does The Shack teach that God is a woman or that all humans go to Heaven? Is the book more ârealâ or authentic than other Christian fiction? Has William Paul Youngâs bestselling book, which is now also a film adaptation, been wrongly treated by critics and pastors?

Short answer to all of these triune questions: yes. But perhaps not in the ways you think.

In The Shackâs own spirit of ânot in the ways you think,â letâs explore seven more lies Christians believe about The Shack, asking and answering these questions as fans of both biblical faith and fantastical stories. First, make sure you start with the first six lies here.

Lie 7: âThe Shack has a single false/true view.â No, itâs complicated.

Young continues to identify as the sole author of The Shack. The bookâs actual authorship is a bit more complicated. There was even a lawsuit about it. In the end, author and publisher Wayne Jacobsen also speaks as the bookâs coauthor (with Brad Cummings), stating flatly, âPaul isnât the only author of this story.â So the book was written/edited by committee, and only later picked up for larger distribution by Hachette Book Group.

Young continues to identify as the sole author of The Shack. The bookâs actual authorship is a bit more complicated. There was even a lawsuit about it. In the end, author and publisher Wayne Jacobsen also speaks as the bookâs coauthor (with Brad Cummings), stating flatly, âPaul isnât the only author of this story.â So the book was written/edited by committee, and only later picked up for larger distribution by Hachette Book Group.

This joint authorship, like with some written-by-committee blockbuster movies, may help explain some of the clashing tones and ideas within the story. It helps explain why The Shack sounds so biblical at one moment, as demonstrated in part 1 and as shown here:

- âCreation and history are about Jesus. He is the very center of our purpose, and in him we [I would add: that is, redeemed Christians] are now fully human.â

- âThere has never been a question that what I [God] wanted from the beginning, I will get.â Here Young, et. al. implicitly denies the false âopen theismâ notion, that not even God can foresee future events and is operating with some element of risk.

- The Triune God doesnât need others (including human beings) to be fulfilled. Instead, God lacks nothing, being already âloveâ among His Persons.

⊠But then The Shack offers clashing notions such as that although God always gets what s(he) wants, s(he) either does want to allow evil and suffering for good reasons, and/or is helpless when an evildoer abducts and kills a child.

Moreover, if one author (Jacobsen) says he does reject universalism, but another author (Young) very clearly accepts it, that puts a crucial religious divide at the heart of the story. Unlike the unified God the authors wish to explore, this trinity of human authors is not very well unified. Thus the bookâs narrative voice(s) become unreliable and self-conflicting.

Lie 8: âThe Shack is better fiction.â Itâs often poorly written.

Some fans of The Shack have praised the book as if it is better than most evangelical fare. I began the book at least hoping for good writing. But soon I sensed The Great Sappiness:

[Mack] hit hard, back of the head first, and skidded to a heap at the base of the shimmering tree, which seemed to stand over him with a smug look mixed with disgust and not a little disappointment.

Yes, Mack wanted more, and he was about to get much more than he bargained for.

Summer wildflowers began to color the borders of the trail and the forest as far as he could see. Robins and finches darted after one another among the trees. Squirrels and chipmunks occasionally crossed the path ⊠[deer, flowers, fragrances, anything except city-based imagery that the Bible also favors to describe paradise (Rev. 21), and then âŠ] The dilapidated shack had been replaced by a sturdy and beautifully constructed log cabin, now standing directly between him and the lake, which he could see just above the rooftop. ⊠Smoke was lazily wending its way from the chimney into the late-afternoon sky ⊠A walkway had been built to and around the front porch, bordered by a small white picket fence.

This scene is identical to a Thomas Kinkade painting; The Shack has become The Cottageâą.

This scene is identical to a Thomas Kinkade painting; The Shack has become The Cottageâą.

But The Great Sappiness isnât limited to the settings. Mackâs daughter Missy acts and speaks like an iconic perfect little girl, the kind seen in Sherwood Pictures movies (complete with tragedy like her Courageous counterpart). Ideas also smack of reality-denying sentiment:

- Forgiveness is not a moral exchange between human beings; it is primarily an emotion. Yet somehow you can still feel angry even after âforgivingâ someone. Forgiveness does not even have real effects to restore relationship between people.

- Papa says, âThere is power in what my children declare,â a nod to prosperity gospel and/or American-Christian dream teaching.

- âIt is a tree of life, Mack, growing in the garden of your heart.â

- Also, ten points from Young for severely dated The Matrix references.

Some may object: wait, isnât The Shack more like Christian classics such as âThe Chronicles of Narniaâ that more fully engage deeper ideas and push imagination? Unfortunately, no, The Shack is not like the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, George MacDonald and others Young credits for âcreative stimulation.â Christians may like to drop these names for credit by self-association. But we often do not see why these classic works last while others fade. For example, Lewis believed in the value of old poets and myths to teach us, including the âtrue mythâ of the Bible. Young gets this exactly backward: it is he who will instruct the old myths. He will put them in their place. And alas, despite all the story’s pleas for doctrinal humility, this is perhaps the greatest form of religious arrogance hidden in The Shack.

Therefore, I doubt the book (and movie) will have much cultural impact beyond Christian and nominally Christian audiences. It offers familiar images and tropes of the most shallow kinds of Christian fiction, only turned up to 11, yet offers even less biblical truth than those.

Lie 9: âThe Shack deals honestly with evil and pain.â It denies them.

The Shackâs preference for sentimentalism is clearest when it seeks to address the themes of evil and suffering. This is no false expectation by doctrine police, but the bookâs own mission. Its cover slogan is, âWhen Tragedy Confronts Eternity.â The back cover promises:

The Shackâs preference for sentimentalism is clearest when it seeks to address the themes of evil and suffering. This is no false expectation by doctrine police, but the bookâs own mission. Its cover slogan is, âWhen Tragedy Confronts Eternity.â The back cover promises:

In a world where religion seems to grow increasingly irrelevant The Shack wrestles with the timeless question: “Where is God in a world so filled with unspeakable pain?”

The Shack does not wrestle. It merely gives this question a mere slap on the wrist with a lace-trimmed glove.

Its ill treatment begins with a writing style that hovers over characters and does not go inside. We do not truly feel Mackâs sadness. Verbiage adds distance, not intimacy. His emotions even have their own distinct title, like an album: The Great Sadness.

Mackâs denial of emotions is also bashed into our heads with sentences like, âWith every effort he could muster, he kept himself from falling back into this black hole of emotions.â (Really? So not confronting these negative emotions is bad? Or could this be a bit clearer?)

Perhaps worst of all: Any real impact of these terrible eventsâthat Mackâs daughter is abducted, presumably raped, and murderedâis blunted by the storyâs gross assurances: itâs not as bad as we think, God manifested to Missy to lessen her terror, and spoke to her heart, and Missy even prayed right then for her fatherâs peace. Here and elsewhere, The Shack refuses to show human evil and suffering closer to their realistic worst. Even as the authors teach us that Mackâs denial of emotions = bad, weeping = good, they deny us real reasons to weep. This is The Shack at its most sticky and saccharine, and I felt offended by its entire implication.

Even worse, all of a sudden, this one encounter with “God” fulfills all eschatological hope in Mackâs soul. âHis constant companion, The Great Sadness, was gone. ⊠The Great Sadness would not be part of his identity any longer.â âThe Great Sadness is gone âŠâ To be sure, happy endings should occur in books. But not like this, and not if you promise your book will skip past all that irrelevancy of corny religion and really dig its hands into the worldâs crap. In reality, God does not heal our hearts so quickly. To claim otherwise is to tell a great lie.

What then of existing biblical, historical, and/or philosophical responses to the problem of evil and suffering? The Shack does not care for them. It does not let previous Christian teaching even speak for itself. Bad âseminaryâ answers and book-learninâ lurks in the background, barely even allowed to fling a black cape versus the supposedly better answers Mack is taught in the titular shack. Perhaps the reader can therefore imagine their own villain back there (such as that one pastor/ministry/belief the reader especially despises). But this is not the role of a story that gets real and represents its antagonism brutally. It is the role of propaganda.

Lie 10: âThe Shack doesnât really preach that God is like a woman.â In fact, it really does preach this, but not in the way you think.

Critics like to raise a ruckus over The Shackâs portrayal of God the Father, and God the Holy Spirit, as semi-incarnate non-white women. In response, fans defend the book. Coauthor Jacobsen is among them and un-subtly suggests that âfor some [the criticism] may have been more about âblackâ than âwomanâ âŠâ Nonsense. Serious criticism has nothing to do with âGodâsâ skin tone, but with the notion that the other two Persons of the Triune God are in the habit of imitating Jesus and semi-incarnating as shape-shifting humanoids. But all of Scripture, the true myth Young disregards, shows that the Incarnation is Jesus-specific. âHe is the very image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.â

Young, Jacobsen, and others insist the book doesnât really teach God is a human woman. After all, Papa later shape-shifts into a human male one day because, as (s)he explains, âThis morning youâre going to need a father.â So the defense goes: Thatâs just how God needed to be, to help Mack bypass his own stigmas of God and his human father.

But why is that necessary? The Shack doesnât explain. Nor can it bypass the fact that Mack does not relate as easily to âPapaâ (the Father) or âSarayuâ (the Holy Spirit) but rather to the male person of Jesus, similar to the Bible itself. God has already recognized our need for intimacy with Him, despite His initial holy distance from we his enemies. But He does not respond with female âimagery,â but by preserving His self-identification using exclusively male pronouns and dwelling with us as Jesusâwho is neither Father nor Mother but our Brother.

However, The Shackâs main problem isnât the female characters. The author(s) have deeper intent: to show that there are âwomanlyâ virtues, such as relationships, that are closer to Godâs nature than âmaleâ practices, such as power. The book doesnât deny that women sin. But it does suggest that women finding hope apart from God and in human relationships is at least closer to Godâs ideal, while men usually behave worse:

“The world in many ways would be a much calmer and gentler place if women ruled. There would have been far fewer children sacrificed to the gods of greed and power.”

Mack shook his head and looked up. âSo, I donât really understand reconciliation and Iâm really scared of emotions. Is that about it?â

Papa didnât answer immediately but shook her head as she turned and walked away in the direction of the kitchen. Mack overhead her grunt and mutter, as if only to herself, âMen! Such idiots sometimes.â

This alone might not be bad. But the story offers no female characters who struggle with sin. Women are cast as God-characters or else human icons, such as Mackâs wife, Nan, who rarely speaks, or Missy, who only speaks angelic-evangelical-movie-daughterese.

This alone might not be bad. But the story offers no female characters who struggle with sin. Women are cast as God-characters or else human icons, such as Mackâs wife, Nan, who rarely speaks, or Missy, who only speaks angelic-evangelical-movie-daughterese.

Moreover, the storyâs very notion of some virtues as âmaleâ and others as âfemaleâ seem sexist even for a secular reader. Why canât men be natural nurturers? Why canât women be powerful and yet not sin? Is it evil for a woman to feel anger against an abuser? Must a woman or a man be forced into fake âforgivenessâ of an offender who has violated her or committed violence on her? What if we gender-reversed The Shack in which a woman character confronts her rapist in a paradise vision and, despite having no felt or seen evidence that he has repented or that justice has been done, is compelled to âforgiveâ him?

The Shack simply doesnât engage with a rather mind-blowing notion: God, not human beings, can hold all the virtues. He is the embodiment of each one, while on our own, humans reflect these in limited or even corrupted ways. The Shack simply ignores biblical portrayals of Him as both mercy and vengeance, love and hatred (eternally against sin and unrepentant sinners), distant/unapproachable and up close/personal (Emmanuel, God with us).

Lie 11: âThe Shack doesnât promote universalism.â No. It does.

Universalism is the false belief that God will somehow, eventually, redeem all individual humans and will not need to torment some humans for eternity.

The Shack coauthor Jacobsen denies he is a universalist in very plain and helpful terms:

Perhaps the most problematic accusation is that The Shack promotes universalism, the belief that everyone gets salvation in the end. Some who advance this idea quote from Paul Youngâs paper for a think tank written before The Shack. Even today he describes himself as a âhopeful universalistâ. ⊠When [Young] first sent me the manuscript, universalism was a significant component in the resolution of that story. When he asked for my help in publishing the book, I told him I wouldnât work on it if [universalism] was his answer to human suffering. I didnât agree with it and thought it would hamper efforts to reach the audience that would most benefit from the book.

To his credit, Jacobsen contends a more-biblical view of eternal punishment:

I donât have to figure it all out, but trust it to the God I know. However, nothing Jesus, Paul, or John said points me to the conclusion that everyone receives salvation. In fact they warn of significant consequences in the age beyond for refusing Godâs love in this one. I do believe Godâs love is universal and his desire is for everyone to be saved, but that transaction involves a response from us.

But Young is absolutely, in no equivocal terms, a universalist, and equally boldly states:

Are you suggesting that everyone is saved? That you believe in universal salvation?

That is exactly what I am saying!

Hereâs the truth: every person who has ever been conceived was included in the death, burial, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus.

Biblical Christians ought to respond in sober horror and repeat the words of the apostle Paul: âBut even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed.â

But if Jacobsen denies universalism and Young affirms it, what is actually in The Shack?

In a word: universalism.

Unfortunately, The Shack must answer for itself without helpful (and contradictory) input from behind the scenes. And by itself the story does support the heresy of universalism.

I found the universalism part in The Shack.

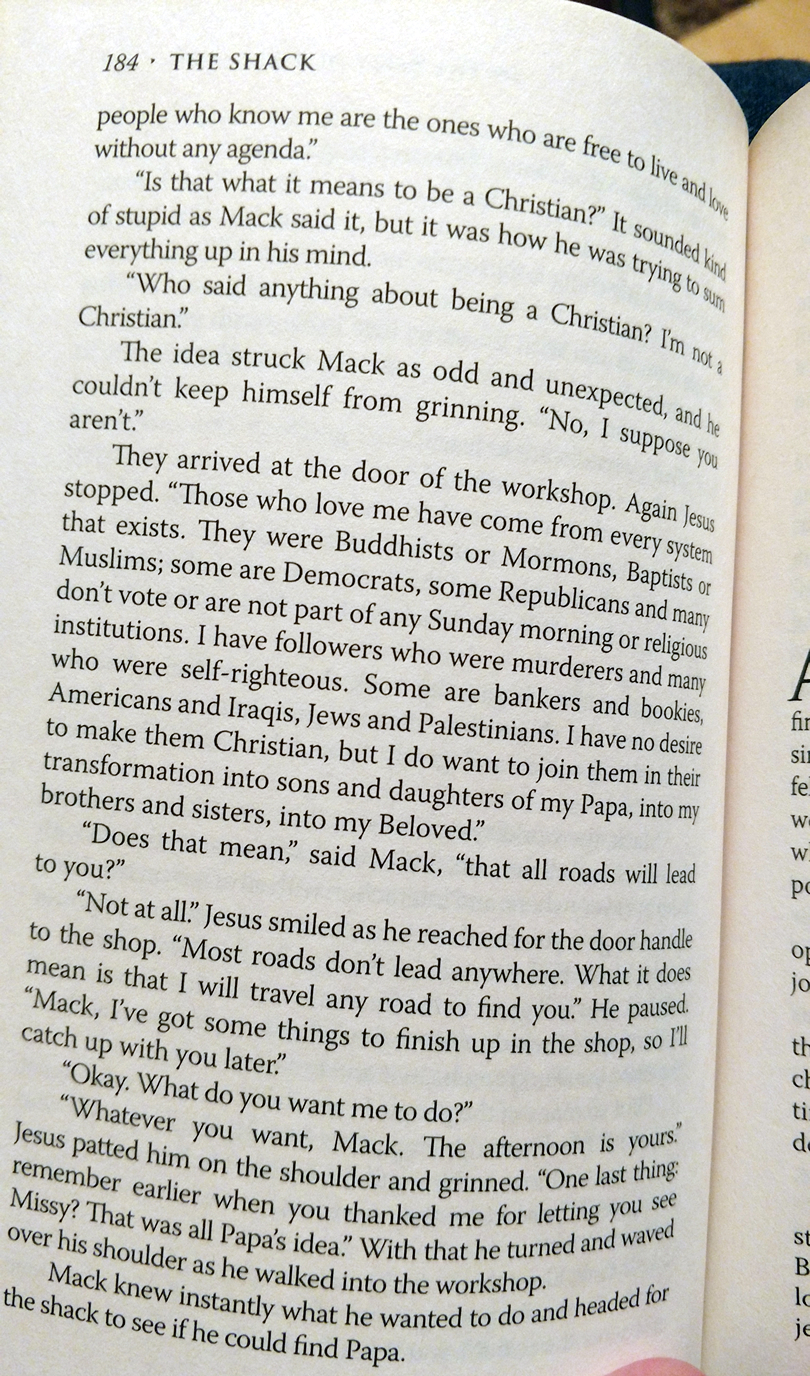

However, itâs clear from what we read that at least two authors wanted to have the story go both ways. Ultimately they seem to have settled on a political compromise. âJesusâ tells a surprised Mack (Mack spends a lot of time surprised), âWho said anything about being a Christian? Iâm not a Christian,â as if this proves anything. To The Shackâs credit, he then offers a list of various religions and sins previously practiced by his followers. But then:

âI have no desire to make them Christian, but I do want to join them in their transformation into sons and daughters of my Papa, into my brothers and sisters, into my Beloved.â

âDoes that mean,â said Mack, âthat all roads will lead to you?â

âNot at all.â Jesus smiled as he reached for the door handle to the shop. âMost roads donât lead anywhere. What it does mean is that I will travel any road to find you.â

Again, The Shack is not simply fiction. One canât resort to that rebuttal. It is a sermon, with âsaid Mackâ and other attributions inserted to make it dialogue. The author(s) want you to adopt this belief. And this belief is universalism. No, all roads wonât lead to Jesus, and Jesus has imposed limits on His own grace (what they are is up for debate), and most roads also wonât lead simply to nothing. Many will lead to Hell, the place God prepared for everlasting torment for the devil and his angels, and for unrepentant human rebels. If Christians write stories like this about where other religious âroadsâ lead, and do not care to mention the threat of Godâs wrath, they are complicit in universalism. They are hurting and hating, not loving, their neighbors by allowing and promoting such a false teaching.

What I say next, I say carefully but firmly: Damn it to hell. May God grant these false teachers repentance, so that someday in the New Earth we can together laugh about all this.

Lie 12: âIf you enjoyed The Shack, youâre a bad Christian.â Tastes vary.

However: all of this does not mean all fans of The Shack should necessarily feel guilty!

However: all of this does not mean all fans of The Shack should necessarily feel guilty!

Some critics of The Shack may imply that all its fans are compromisers or universalists. This is simply not the case. After all, I read the book. Iâm not a heretic or a universalist. If you read the book, and you know that youâre not, then youâre not. Let no one tell you otherwise.

As I concluded in lie 6, you may feel very helped by the book. If so, great. Thank God for that. He can indeed use anything to work His will. Even false teaching. Even cancer.

You donât need to throw away or burn your copy of The Shack.

However, please also consider this wisdom from Shannon McDermott:

Human feelings, no matter how spiritual they may seem, are not incontrovertible proof of Godâs work; Godâs work is not necessarily a seal of approval on His instruments. Maybe God has used The Shack, as people say, but you know, He used Pharaoh, too.

That The Shack makes you feel (correctly) that God is love doesnât mean that it isnât wrong in other respects; neither does it make significant errors all right. And itâs not enough to feel rightly about God; we need to think rightly about Him, too. Even the feeling that God is love, without any feeling that He is also majestic and terrifyingly holy, leaves us stranded a long way from home.

Also keep in mind that Christiansâ tastes will vary. Even apart from The Shackâs overall bad theology, I did not like the book. Many others will feel the same. But I can certainly see its appeal to Christians whoâve struggled with legalistic upbringings. If youâve been starved for the image and themes of a loving, embracing God, naturally this book will meet that needâat least at first. But go âfurther up and further in.â Chase the stream to the Bibleâs real truth of our perfectly loving and perfectly just King, who shows true mercy and justice alike.

Lie 13: âYou defeat The Shack fans only by preaching.â Wrong.

Finally, if youâre a doctrine-wonk like I am, and kind of like to pick on The Shack and other false teaching, may I urge you: chill out a bit. Mind your place. Literally, mind your place.

Imagine being in church, hearing a sermon error, and standing up to disagree. Thatâs rude.

Now imagine walking into a library meeting room. Here, several people are reading a book and discussing it. You ignore the circle, the chairs, the cookies. You bring in a lectern and portable speaker. You set it up, and commence to preach. Is this appropriate? No. Itâs rude!

Many (not all) critics of The Shack are right to engage with the book as if itâs a sermon, because it is. However, they are wrong to try to engage with the book only as preachers.

If people are sitting around reading or discussing a book, then this is a book club. You canât be preacher today. You must first be a human being in a book club. So follow the book club rules. That means you read the book (always a plus) and first, listen. Do your best to make people feel you are listening. Listen not only to the book but to its fans. Find the bookâs good points, if you can. And always emphasize with peopleâs positive responses, while also acknowledging that God can use anything, even lies and cancer, to draw people to Himself.

Share your feelings too. Donât be the clichĂ©d Bad Male who Canât Connect with His Feelings and Thatâs Bad. After all, when you only talk in âfacts,â that leaves a legitimate opening for people to accuse you of simply âfearingâ other ideas.

On the way, actually engage the bookâreally engage with it. I commend the âpopologeticsâ method by Ted Turnau, which I have occasionally followed in this two-part article:

- Whatâs the story?

- What kind of world are we exploring?

- What is good, true, and beautiful about this story-world?

- What is bad, false, and ugly about this story-world, denying us the storyâs promises?

- How does the actual Gospel of Jesus Christ fulfill good promises the story canât keep?

Point 4 is especially valuable, because The Shack values its own sermons over story, offers conflicting âtruthsâ as well as mainly sentimental and fleeting beauties, at best flirts with damnable and false teaching, and violates Godâs true love and justice (which are far more fulfilling). Before we even go to the Bible to compare The Shack with Godâs own revelation, we find The Shack simply cannot fulfill its own promises to offer a better story about Him.

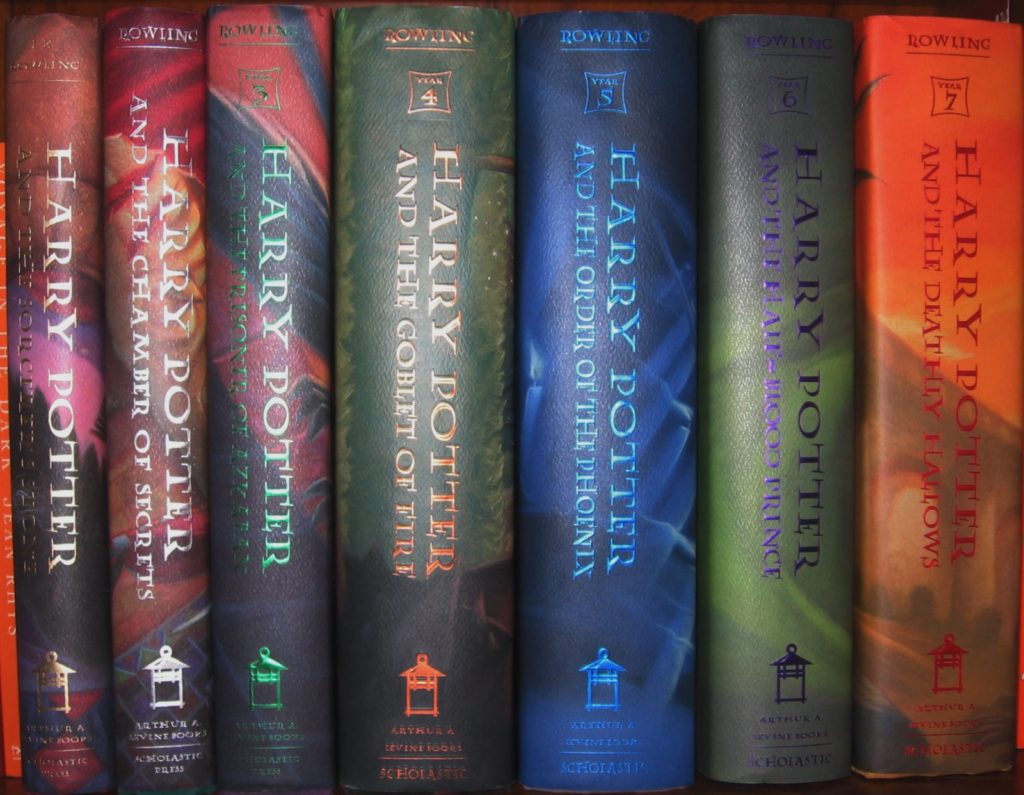

Like basketball, quidditch is a popular sport. The athletes that make a team automatically achieve higher status, and the stars earn the admiration of fans. Also like basketball, quidditch is played at schools, and by young people in “pick up” games.

Like basketball, quidditch is a popular sport. The athletes that make a team automatically achieve higher status, and the stars earn the admiration of fans. Also like basketball, quidditch is played at schools, and by young people in “pick up” games.  Quidditch differs from basketball in some ordinary ways, too. The game requires seven players on a side, not five. The captain of each team also operates as the coach, and only he may call a time out. Quidditch utilizes three balls, not one. Bludgers are designed to knock players off their brooms. The quaffle is the ball used to score points, much as a basketball is used to score by being shot through a hoop. Finally, the snitch, the smallest of the balls, is the key to quidditch. When a seeker of either team captures the snitch, the match is over.

Quidditch differs from basketball in some ordinary ways, too. The game requires seven players on a side, not five. The captain of each team also operates as the coach, and only he may call a time out. Quidditch utilizes three balls, not one. Bludgers are designed to knock players off their brooms. The quaffle is the ball used to score points, much as a basketball is used to score by being shot through a hoop. Finally, the snitch, the smallest of the balls, is the key to quidditch. When a seeker of either team captures the snitch, the match is over.  I could continue enumerating the ways basketball and quidditch are alike or different, but the key when it comes to J. K. Rowling’s worldbuilding is that she used something familiar—whether “football,” rugby, dodgeball, or basketball—and made something new, not simply by mixing the various sports, but by making magic a key component.

I could continue enumerating the ways basketball and quidditch are alike or different, but the key when it comes to J. K. Rowling’s worldbuilding is that she used something familiar—whether “football,” rugby, dodgeball, or basketball—and made something new, not simply by mixing the various sports, but by making magic a key component.

think of what Ravi Zacharias called his radio program: “Let My People Think.”

think of what Ravi Zacharias called his radio program: “Let My People Think.”

In the fictional world of 2073, cities comprise the largest economic centers of the worldâs nineteen providences. Outworlds are inhabited by non-citizens. Some are defectors who gave up their citizenship for more personal freedom. The largest and most organized of these outworlds is The Network, a series of six communities formerly known as states. They have become illegally self-governing. However, the Network is the largest provider of food for the cities. They have been allowed to exist in return for a tithe of goods. However, their growth threatens the concept of a global government.

In the fictional world of 2073, cities comprise the largest economic centers of the worldâs nineteen providences. Outworlds are inhabited by non-citizens. Some are defectors who gave up their citizenship for more personal freedom. The largest and most organized of these outworlds is The Network, a series of six communities formerly known as states. They have become illegally self-governing. However, the Network is the largest provider of food for the cities. They have been allowed to exist in return for a tithe of goods. However, their growth threatens the concept of a global government. Winner of the 2012 Selah Award and Carol Award finalist LINDA WOOD RONDEAU writes to demonstrate our worst past, surrendered to God becomes our best future. After a long career in human services, Linda now resides in Jacksonville, Florida. Readers may visit her web site at

Winner of the 2012 Selah Award and Carol Award finalist LINDA WOOD RONDEAU writes to demonstrate our worst past, surrendered to God becomes our best future. After a long career in human services, Linda now resides in Jacksonville, Florida. Readers may visit her web site at

It wouldnât even make sense to claim The Shack has only lies or heresy. Wise Christians who believe in biblical truth have always also believed the most effective and believable lies are those mixed with truth. Thatâs why the apostles teach us to practice discernment. This means sorting truth from error, because the two are often mixed up in complex ways.

It wouldnât even make sense to claim The Shack has only lies or heresy. Wise Christians who believe in biblical truth have always also believed the most effective and believable lies are those mixed with truth. Thatâs why the apostles teach us to practice discernment. This means sorting truth from error, because the two are often mixed up in complex ways.

The road took a sudden turn between two high buildings. Just beyond, a dazzling display caught my eye. A giant cardboard cutout in the likeness of a man in a business suit and sunglasses. Bolded letters declared him as âGenius billionaire playboy philanthropist.â

The road took a sudden turn between two high buildings. Just beyond, a dazzling display caught my eye. A giant cardboard cutout in the likeness of a man in a business suit and sunglasses. Bolded letters declared him as âGenius billionaire playboy philanthropist.â

The fact is, pop culture, and Disney right along with others, has been pushing agendas that clash with God’s moral standards for as long as there has been pop culture. Perhaps we have unconsciously believed that fairy tales were safe places, that the taint of sin would not spoil a happily-ever-after story told to children. After all, fairy tales came into being in part as cautionary stories to lead children into right moral thinking.

The fact is, pop culture, and Disney right along with others, has been pushing agendas that clash with God’s moral standards for as long as there has been pop culture. Perhaps we have unconsciously believed that fairy tales were safe places, that the taint of sin would not spoil a happily-ever-after story told to children. After all, fairy tales came into being in part as cautionary stories to lead children into right moral thinking. We expose deeds of darkness, I think, by pouring light on them. When we hold up Christ, when we show Him as the One who rescued us from the kingdom of darkness, the distinction between the two is clear. Mordor or Gondor? Aragorn or Sauron? The White Witch or Aslan?

We expose deeds of darkness, I think, by pouring light on them. When we hold up Christ, when we show Him as the One who rescued us from the kingdom of darkness, the distinction between the two is clear. Mordor or Gondor? Aragorn or Sauron? The White Witch or Aslan?