The Chronicles of Sarco Book 1

By Joshua A. Johnston

INTRODUCTION—Edge Of Oblivion

A Forgotten Past. A Terminal Future.

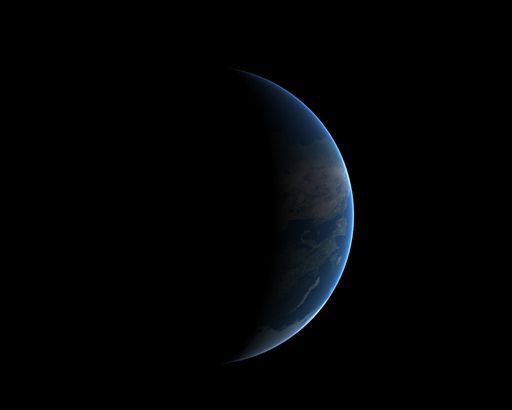

Earth has emerged from a cataclysmic dark age with little knowledge of its past. Aided by the discovery of advanced alien technology, humanity ventures into the stars, joining other sentient races in a sprawling, prosperous interstellar Confederacy.

That peace is soon shattered. Without warning, the Confederacy comes under attack by an unstoppable alien force from the unknown regions. With hopes for civilization’s survival dwindling, Commander Jared Carter is sent to pursue an unlikely lead: a collection of ancient alien religious fragments which mayâor may notâhold the key to their salvation …

EDGE OF OBLIVION — EXCERPT

Prologue

An end, an end is come upon the four corners of the land.

Now is the end come upon thee,

And I will send mine anger upon thee,

And I will judge thee according to thy ways,

And will recompense upon thee all thine abominations.

And mine eye shall not spare thee, neither will I have pity,

But I will recompense thy ways upon thee,

And thine abominations shall be in the midst of thee . . .

An evil, an only evil, behold is come.

An end is come, the end is come: it watcheth for thee; behold it is come.

—Excerpt from a Human religious text, origin unknown

It came as an envoy to the Master’s will.

Across the Deep Reaches it came, bending to the will of the Master . . . and in turn bending all before it to that same will.

The Master declared that it was Malum, and thus it was so.

* * *

Malum’s knowledge was vast. It stored the knowledge of aeons across galaxies: lifetimes, empires, planets, the fabrics of civilization and technology, the knowledge of life and death. Yet it drew on it only insofar as it served the Master. When knowledge was needed, the barriers shifted to make the new relevance the only knowledge in Malum’s existence, the rest as lost as if it had never been known.

The invisible barriers of eternal information shifted, parting to focus in on the constellation of stars that now floated before it. In Malum’s memory words flared to life. Aecron. Ritican. Hazionite. Human. Exo. Confederacy.

Aecron. Homeworld designate Aeroel. Superior intelligence, fragile physiology. Arrogant, unskilled in diplomacy. First in Confederal region to develop interstellar fold technology, used it to observe and intermittently experiment on pre-spaceflight Human and Hazionite homeworlds. Policies changed after attack by extra-regional fleet designate Invaders of 1124. Invader origins not known to Aecrons, though known to Master. Invaders repelled, effected change in Aecron disposition; Aecrons cultivated alliances with other races reaching spacefaring status as defense against future attacks. Aecrons conform to will of Master, unaware.

Ritican. Homeworld designate Ritica. Durable physiology, high tolerance for temperature. Methane respiration. Intelligent, developed interstellar travel after Aecrons but independently of them. Sociology revolves around nonviolent coexistence unless attacked; retaliatory psychology, relentless, brutal. Exemplar” Corridor Wars; Ritican counterattack led to near-genocide of Hazionites. Current Hazionite and Ritican relationship nonviolent but complicated, potential for exploitation. Ritican militia most powerful military force in Confederacy.

Hazionite. Homeworld designate Hazion Prime. Matriarchal society. Olfactory senses allow for enhanced perception of emotion. Moderate intelligence, expansionistic disposition. Fold drive reverse-engineered from Aecron ship wreckage found on homeworld. Invasion of Ritican territory precipitated Corridor Wars; Ritican retaliation resulted in near-annihilation of Hazionites before Human intervention ended conflict. Treaty designate Titan Accords ended Corridor Wars, established Confederacy.

Human. Homeworld designate Earth. Moderate intelligence, skilled in diplomacy and politics. Little surviving recorded Human history prior to 1300 homeworld revolutions antecedent; cataclysm on ancient Earth led to loss of most knowledge through period designate Dark Ages. Cause of Earth cataclysm and loss of Human history unknown to Humans. Fold drive reverse-engineered from Aecron ship wreckage found on homeworld. Human diplomats intervened to end Corridor Wars, create Confederacy. Highly influential in Confederacy; Human language and measurements nor in Confederal commerce and trade.

Exo. Homeworld designate Exo Homeworld. Exo name given by Human diplomats. Exoskeletal physiology, extraordinary durability, capable of short periods of time in open space. Asexual, highly individualistic, oriented predominantly around task completion. Capacity for mechanical, engineering work without equal in Confederacy; intellectual processes are concrete, lacking in artistic or creative function. No formal governance, no family structure.

Confederacy. Capital designate Nevea, Human homeworld system, planet designate Titan. Facilitates interspecies commerce and trade, organizes Confederal Navy to protect sentient merchants from piracy. Maintains some contact with non-allied sentients designate Minor Races: pirate society Ussonian, reclusive Tullasph, multiple pre-spaceflight civilizations.

* * *

Malum absorbed the full knowledge of the Confederacy and its component societies, became as much the knowledge as it was itself. Malum organized the knowledge for the purpose that lay before it, for the knowledge itself was not an end, but a means to the will of the Master.

* * *

First came Gor-Exxus. A Ritican frontier listening post orbiting an aging white dwarf. Isolated, neglected even by pirates. Fifty Riticans present. Most received the assignment as punishment, viewed it with resentment. It was not a vigilant defense, although Malum knew it would not matter either way. This was not a matter of hubris, but fact.

Malum folded in on the listening post, drew near. It sensed the station probing, questioning. It felt the malaise become confusion, the confusion become worry. The station sent a message to other stations.

Malum unleashed its power. The worry turned into terror, then was silenced.

Malum departed, leaving nothing behind.

AUTHOR BIO

Joshua A Johnston was raised on science fiction television and film before being introduced, in his teenage years, to the wider universe of science fiction literature. In addition to his daily work teaching American history and American government, he is an occasional writer on a variety of topics, including video games and parenting. You can find him online at www.joshuaajohnston.com.

Joshua A Johnston was raised on science fiction television and film before being introduced, in his teenage years, to the wider universe of science fiction literature. In addition to his daily work teaching American history and American government, he is an occasional writer on a variety of topics, including video games and parenting. You can find him online at www.joshuaajohnston.com.

Edge Of Oblivion is Christian science fiction published by Enclave Publishing in April 2016. It’s available through Amazon and other fine book distribution centers.

The deeper we feel a connection, the more the story stirs within our hearts and minds a sense of longing, of understanding, of meaning.

The deeper we feel a connection, the more the story stirs within our hearts and minds a sense of longing, of understanding, of meaning. The interesting thing is, all those lives we read about? Theyâre all facets of a prism reflecting our experiences back to us.

The interesting thing is, all those lives we read about? Theyâre all facets of a prism reflecting our experiences back to us.

But more underrepresented are evangelical Christians. There have been and are some TV programs that feature openly Catholic characters (e.g., Father Dowling Mysteries from some time ago and Blue Bloods more recently.) But characters that hold an evangelical perspective, who pray, read their Bible, go to church, believe in Christ as their Savior . . . these characters have been set aside. Once a surprising number of shows had at least the external trappings of the life of a Christian, but no more.

But more underrepresented are evangelical Christians. There have been and are some TV programs that feature openly Catholic characters (e.g., Father Dowling Mysteries from some time ago and Blue Bloods more recently.) But characters that hold an evangelical perspective, who pray, read their Bible, go to church, believe in Christ as their Savior . . . these characters have been set aside. Once a surprising number of shows had at least the external trappings of the life of a Christian, but no more.

Joshua A Johnston was raised on science fiction television and film before being introduced, in his teenage years, to the wider universe of science fiction literature. In addition to his daily work teaching American history and American government, he is an occasional writer on a variety of topics, including video games and parenting. You can find him online at www.joshuaajohnston.com.

Joshua A Johnston was raised on science fiction television and film before being introduced, in his teenage years, to the wider universe of science fiction literature. In addition to his daily work teaching American history and American government, he is an occasional writer on a variety of topics, including video games and parenting. You can find him online at www.joshuaajohnston.com.

As Christians, we often find it too easy to avoid dark fiction.

As Christians, we often find it too easy to avoid dark fiction. Iâd like to challenge that notion and suggest we can, and should, be willing to read stories that donât fit the prescribed model of clean fiction. Not because we enjoy the guilty pleasure or want to vicariously participate in the immorality, but because it presents truth.

Iâd like to challenge that notion and suggest we can, and should, be willing to read stories that donât fit the prescribed model of clean fiction. Not because we enjoy the guilty pleasure or want to vicariously participate in the immorality, but because it presents truth. The biggest problem I see with so-called clean fiction is the subtle mistruth it presents by offering us artificial stories.

The biggest problem I see with so-called clean fiction is the subtle mistruth it presents by offering us artificial stories. What is the comfort of sunshine without the gloom of shadow?

What is the comfort of sunshine without the gloom of shadow?

So the ideas C. S. Lewis espoused, even ones taken out of context, apparently, ought not be tolerated. Was Lewis giving offense? Or are those who disagree with him simply offended because they find his conclusions in contradiction to their own?

So the ideas C. S. Lewis espoused, even ones taken out of context, apparently, ought not be tolerated. Was Lewis giving offense? Or are those who disagree with him simply offended because they find his conclusions in contradiction to their own? I’ve long said that Christians are not to be offensive in the way we speak, but the Bible itself says the message of the gospel is offensive to those who are perishing. To tell people they are sinners, is offensive. To say that some are saved and some are not, is to appear in the eyes of our culture to be discriminatory. To be hateful. To hold a position that ought not to be tolerated.

I’ve long said that Christians are not to be offensive in the way we speak, but the Bible itself says the message of the gospel is offensive to those who are perishing. To tell people they are sinners, is offensive. To say that some are saved and some are not, is to appear in the eyes of our culture to be discriminatory. To be hateful. To hold a position that ought not to be tolerated.

Bethany A. Jennings, whose name you might recognize because she’s won a few Spec Faith Writing Challenges, is a YA science-fiction and fantasy author, and a chronic night owl. She is endlessly passionate about the power of speculative fiction, both to shape hearts and cultures and to unveil hidden realities. Bethany can be found wrangling her toddlers, running Twitter events, or inventing new kinds of sandwiches—but no matter where she is, worlds and stories are dancing in her head. Born a southern California girl, she now lives in New Hampshire with her husband and four children, zero pets, and a large collection of imaginary friends (a.k.a. her fictional characters). In addition to her fiction writing, she is a freelance editor, blogger, and the organizer of #WIPjoy, a seasonal online event for authors.

Bethany A. Jennings, whose name you might recognize because she’s won a few Spec Faith Writing Challenges, is a YA science-fiction and fantasy author, and a chronic night owl. She is endlessly passionate about the power of speculative fiction, both to shape hearts and cultures and to unveil hidden realities. Bethany can be found wrangling her toddlers, running Twitter events, or inventing new kinds of sandwiches—but no matter where she is, worlds and stories are dancing in her head. Born a southern California girl, she now lives in New Hampshire with her husband and four children, zero pets, and a large collection of imaginary friends (a.k.a. her fictional characters). In addition to her fiction writing, she is a freelance editor, blogger, and the organizer of #WIPjoy, a seasonal online event for authors.

Plus it needs to add a punch that needs to grab us by the collar and refuse to let go.

Plus it needs to add a punch that needs to grab us by the collar and refuse to let go. I think the best opening lines raise questions. My personal favorite from the lists above is the one about Szeth.

I think the best opening lines raise questions. My personal favorite from the lists above is the one about Szeth.

Perhaps the Harry Potter phenomena or the vampire fixation were passing fads. But perhaps they are reading experiences that are helping to shape the thinking of a generation. Shouldn’t Bible-believing Christians see that as our job?

Perhaps the Harry Potter phenomena or the vampire fixation were passing fads. But perhaps they are reading experiences that are helping to shape the thinking of a generation. Shouldn’t Bible-believing Christians see that as our job?