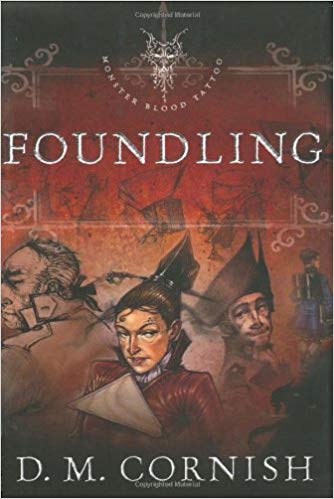

Fiction Friday â Foundling by D. M. Cornish

Foundling

Monster Blood Tattoo, Book 1

by D. M. Cornish

INTRODUCTION—FOUNDLING

Middle Grade/Young Adult Fantasy

“The Half-Continent is a world at war: humans and monsters have been fighting for centuries. Biotechnology supplies light, engine power and even, in some cases, superhuman powers. Our hero, Rossamund, leaves the protected, if not fully comfortable, world of the orphanage where he was raised to start a career as a lamplighter outside the city walls. Early in his travels he is diverted from his true path and we discover the Half-Continent and its inhabitants through his adventures. The world is rendered with thoughtful and convincing detail, complemented by the author’s own illustrations and an extensive set of appendices (the ‘Explicarium.’)

“In truth, Foundling is more of a first act than a first book: characters are introduced, mysteries are suggested, the scene is set; but the arc is not complete.”

FOUNDLING — EXCERPT

MADAM OPERA’S ESTIMABLE MARINE SOCIETY FOR FOUNDLING BOYS AND GIRLS

vinegaroon (noun) also sailor, mariner, seafarer, mare mam, bargeman, jack, limey (for the limes he sucks when out to sea), mire dog, old salt, salt, salt dog, scurvy-dog, sea dog or tar: those who work the might cargoes and rams that tame the monster-plagued mares and ply the many-colored waters of the vinegar seas. Such is the poisonous and caustic nature of the oceans that even the spray of the waves scars and pits a vinegaroon’s skin and shortens his days under the sun.

The great Skold Harold stood his ground. His comrades, his brothers-in-arms, had all fled in terror before the huge beast that stalked their way. This beast was enormous and covered with vicious, venomous spines. The Slothog—the slaughterer of thousands, the smiter of tens of thousands. The gore of the fallen dripped from its grasping claws as it came closer and closer. Struggling beast-handlers were dragged along as the Slothog strained against its leash.

The battle had been long and bloody. Ruined bodies lay all about in ghastly piles that stretched away as far as the eye could see. Harold had fought through it all. His once-bright armor was bruised and dented beyond repair. With great heaviness of heart he checked his canisters and satchels: all his potives were spentâall, that is, but one. It would be his last throw of the dice. He fixed the potive in his sling and, taking up the Empire’s glorious standard, cried, “To me, Emperor’s men! To me! Stand with me now and win yourself a place in history!”

But no one listened, no one halted, no one returned to his side to defend his ancient home.

Alas, now, the Slothog was too close for escape. It paused for a brief and horrible moment. Slavering, it regarded Harold hungrily with tiny, evil eyes. Then, with a bellow it shook off its panicking handlers and charged.

With a cry of his own, lost in the din of the beast, Harold swung up his sling and leaped . . .

“Young Master RossamĂźnd! What rot are yer readin’?’

Fransitart, the dormitory master of Madam Opera’s Estimable Marine Society for Foundling Boys and Girls, stood over RossamĂźnd as he sat in a forlorn little huddle, tucked up in his rickety bunk. A great red welt showed on his let cheek and right down his neck. Gosling had done his work well.

The boy looked sheepishly at Master Fransitart as he pressed the thin folio of paper he had been reading against his chest, creasing pages, bending corners. He had been so taken by the tale that he had not heard the dormitory master’s deliberate step as he had approached RossamĂźnd’s corner down the great length of the dormitory hall.

“It’s one of them awful pamphlets Verline buys for yer, bain’t it, me boy?” Fransitart growled.

It was the old dormitory master who had found him those years ago: found him with inadequate rags and rotting leaves for swaddling, that tattered sign affixed to his tiny, heaving chest. RossamĂźnd knew the dormitory master watched out for him with a care that was beyond both his duty and his typically gruff and removed nature. RossamĂźnd did not pause to wonder why: he simply accepted it as freely as he did Verline’s tender attentions.

The foundling nodded even more sheepishly. The gaudily colored title showed brightly on the cover:

TALES OF DARING FROM THE AGE OF HEROES

He had woken a little earlier, after recovering from his dose of birchet, to find the pamphlet sitting on the old tea chest that served as a bedside table.

X X X X X

AUTHOR BIO—D. M. Cornish

D.M. Cornish was born in time to see the first Star Wars movie. He was five. It made him realize that worlds beyond his own were possible, and he failed to eat his popcorn. Experiences with C.S. Lewis, and later J.R.R. Tolkien, completely convinced him that other worlds existed, and that writers had a key to these worlds. But words were not yet his earliest tools for storytelling. Drawings were.

D.M. Cornish was born in time to see the first Star Wars movie. He was five. It made him realize that worlds beyond his own were possible, and he failed to eat his popcorn. Experiences with C.S. Lewis, and later J.R.R. Tolkien, completely convinced him that other worlds existed, and that writers had a key to these worlds. But words were not yet his earliest tools for storytelling. Drawings were.

He spent most of his childhood drawing, as well as most of his teenage and adult years as well. And by age eleven he had made his first book, called “Attack from Mars.” It featured Jupitans and lots and lots of drawings of space battles. (It has never been published and world rights are still available.)

He studied illustration at the University of South Australia, where he began to compile a series of notebooks, beginning with #1 in 1993. He had read Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast novels, The Iliad, and Paul Gallico’s Love of Seven Dolls. Classical ideas as well as the great desire to continue what Mervyn Peake had begun but not finished led him to delineate his own world. Hermann Hesse, Kafka and other writers convinced him there were ways to be fantastical without conforming to the generally accepted notions of fantasy. Over the next ten years he filled 23 journals with his pictures, definitions, ideas and histories of his world, the Half-Continent.

It was not until 2003 that a chance encounter with a children’s publisher gave him an opportunity to develop these ideas further. Learning of his journals, she bullied him into writing a story from his world. Cornish was sent away with the task of delivering 1,000 words the following week and each week thereafter. Abandoning all other paid work, he spent the next two years propped up with one small advance after the other as his publisher tried desperately to keep him from eating his furniture.

And so Rossamund’s story was born – a labor of love over twelve years in the making.

There are other stories about women, however. Despite its setting in Greek mythology, Wonder Woman is one of the most deeply Christian films Iâve seen in years. Itâs a major-studio movie, and I donât know if the director claims any sort of faith. But its themes of duty, strength, and love drove me to aspire to a more life-changing Christianity. Furthermore, it portrays femininity as complex: a fierce, protective compassion willing to fight to make the world better. Weâre not used to seeing such deep, profound truths about who women can be, and it left me openly weeping in the theater.

There are other stories about women, however. Despite its setting in Greek mythology, Wonder Woman is one of the most deeply Christian films Iâve seen in years. Itâs a major-studio movie, and I donât know if the director claims any sort of faith. But its themes of duty, strength, and love drove me to aspire to a more life-changing Christianity. Furthermore, it portrays femininity as complex: a fierce, protective compassion willing to fight to make the world better. Weâre not used to seeing such deep, profound truths about who women can be, and it left me openly weeping in the theater.

The “wrong” I’m referring to in the title is related to the poll I posted a week ago as part of my post “

The “wrong” I’m referring to in the title is related to the poll I posted a week ago as part of my post “ 4) One last observation: many of the authors and titles that came up in the comments are . . . old. Or older. I think it’s fine to read Chesterton or MacDonald or O’Connor, but if Christian speculative fiction can have the impact on culture that I think it can, we need to be reading what’s coming out today. Who’s read Paul Regnier (science fiction) or Emily Golus (young adult fantasy) or Nadine Brandes (dystopian)? More importantly, who’s writing reviews and letting people know on social media sites what books they ought to be reading?

4) One last observation: many of the authors and titles that came up in the comments are . . . old. Or older. I think it’s fine to read Chesterton or MacDonald or O’Connor, but if Christian speculative fiction can have the impact on culture that I think it can, we need to be reading what’s coming out today. Who’s read Paul Regnier (science fiction) or Emily Golus (young adult fantasy) or Nadine Brandes (dystopian)? More importantly, who’s writing reviews and letting people know on social media sites what books they ought to be reading?

The races, super-intelligent and practically immortal, are about equal in ability but polar opposites in nature. Multiple galaxies are not big enough for the both of them, and the benevolent aliens, thinking long-term, hatch a plan: They will find some promising planet and, over the course of thousands of generations, âdevelopâ a new race to outstrip their rivals and finally take the place of Guardians of Civilization.

The races, super-intelligent and practically immortal, are about equal in ability but polar opposites in nature. Multiple galaxies are not big enough for the both of them, and the benevolent aliens, thinking long-term, hatch a plan: They will find some promising planet and, over the course of thousands of generations, âdevelopâ a new race to outstrip their rivals and finally take the place of Guardians of Civilization.

Let me be honest about something else: as a creative person, I am connected with many other creative types on social media. Yet hardly a day goes by when I don’t come across something that makes me think, “Ugh! How can you like that?” This thought often enters my mind when I see something related to the extreme side of the horror genre, such as torture porn, splatterpunk, cannibal horror, etc.

Let me be honest about something else: as a creative person, I am connected with many other creative types on social media. Yet hardly a day goes by when I don’t come across something that makes me think, “Ugh! How can you like that?” This thought often enters my mind when I see something related to the extreme side of the horror genre, such as torture porn, splatterpunk, cannibal horror, etc. enjoy watching helpless victims get fictitiously but realistically tortured on screen or in a book.

enjoy watching helpless victims get fictitiously but realistically tortured on screen or in a book.