As a speculative writer thinking about worldbuilding, I’m reminded of one of my favorite shows of all time: Mystery Science Theater 3000. I think itâs the same appeal that draws people to laugh at videos of people falling down—itâs funny to watch, but I also know that it could easily happen to me.

That is, I can laugh along with the Satellite of Love crew at the ineptitude of B-movie directors who canât seem to avoid glaring plot holes, nonsensical âscientificâ explanations, and even monsters with visible puppet strings—all the while knowing that I could fall into similar story-killing traps in the next scene I write.

One of the reasons we love great speculative fiction is that it immerses us in a fantastic world that feels real. And when weâre enjoying a great book, movie, or show, we no longer notice the couch weâre sitting on, the sound of the faucet dripping, or the cat walking on top of us to get our attention. Weâre experiencing the story along with the characters in an almost trance-like state—what fiction theorist John Gardner describes as âthe fictional dream.â

What keeps bad B-movies from being engaging are all the careless mistakes that disrupt that dream—unmotivated character actions, poorly executed dialogue, unconvincing monsters, and anything else that pulls the audience out of the moment and makes them say, âHey, wait a minute!â

Unfortunately, these kinds of illusion-killing mistakes are also common for fantasy and science fiction writers—those who have bravely taken on the complex task of inventing a new world from scratch. While itâs impossible to think through every scientific implication of intergalactic space travel or magical agriculture, worldbuilders should at least pay attention to the things readers will notice—such as rudimentary physics, basic logic, and normal character psychology.

Here are some common worldbuilding errors that can shatter the dream experience:

Extreme environments that arenât well thought-through

Iâll admit, being a fantasy writer has sucked some of the fun out of enjoying pop culture. For example, hereâs what happened after watching the famous âLet It Goâ sequence from Disneyâs Frozen:

Iâll admit, being a fantasy writer has sucked some of the fun out of enjoying pop culture. For example, hereâs what happened after watching the famous âLet It Goâ sequence from Disneyâs Frozen:

Other people: âOh my goodness, that was fantastic! The artistry! The message! I feel so free and validated!â

Me: âOK ⌠but what does Elsa eat in the ice palace?â

Unexplained ice magic emanating from a Norwegian princessâs hands I can accept as part of the fairy tale. But running off to a barren mountain, making a shelter out of ice, and then expecting to survive there with no access to vegetation or even canned goods? Now Iâm distracted from the story.

A writer who creates a speculative world with unusual settings needs to think through physical realities, even if theyâre never overtly explained. This is vital in extreme environments such as lava planets, space stations, or dystopian versions of Earth with dramatically different climates. These are all great settings in theory and can work well. But if the writer canât explain where people grow food or where they go to the bathroom, theyâve failed worldbuilding on a basic level.

An inhospitable environment can be used in speculative fiction, of course, with a bit of creative problem solving. For example, Foundation by Isaac Asimov starts out on Trantor, the capital of the Galactic Empire, a planet that is 100% urbanized. Where can a planet of metal and asphalt grow enough food to support its population of 45 billion? Essentially it canât. Trantor has to depend on agricultural imports from the planets they rule over. If this sounds like a precarious political arrangement, it is, and now things are getting interesting.

No societal implications for magic or technology

If youâve created a world with a game-changing discovery or pervasive magical power, one of your first jobs is to figure out all the irritating and mundane ways people would ruin it for everyone.

For example, if a scientific lab announced that they had discovered a method for practical, affordable teleportation, here are the first two things that would happen:

#1. Someone would demonstrate it on TV/the Internet/the Hive Mind/etc. A genius in a lab coat would give an impassioned speech about how much better the world will now be, all the ways we will save on transportation energy, connect families across the globe, and so forth. It will be a crowning achievement of mankind and very inspiring.

#2. A common criminal would steal the technology, transport themselves into a bank vault, and rob thousands of people blind. Bootleg versions of teleporters would quickly hit the black market. Pandemonium would ensue as security systems are now essentially useless. No one would be safe. Panic. Chaos. The government would step in and create a stringent military state. And someone in a lab coat will lament, âThis is why humanity canât have nice things.â

The point is, you canât introduce cheap teleportation to society and not have issues with theft and espionage and murder. You canât give people time travel and not expect everyone to go back and steal Cleopatraâs jewelry or try to kill Hitler.

The writer has to think through likely societal implications and then either embrace the chaos, or else create logical guidelines why this wouldnât happen. Maybe the knowledge is limited to a select few, and the creators have to guard it from falling into the wrong hands. Or maybe the power is only available to those with special ability or rare magical tools.

Vaguely motivated conflicts

Why is the Dark Nation trying to destroy all that is good and beautiful in the Happy Valley? Well, because theyâre evil, thatâs why! And thatâs what evil people do! They hate flowers and clean water and simple folk, and they love coal dust and terror.

The problem with this common fictional scenario is that first, itâs overused, and second, it doesnât make a lot of sense. Sure, there may be sadists and psychopathic individuals who enjoy evil for its own sake, but it’s unlikely that a whole people group will buy into it.

Think about it: most of us want to consider ourselves good—or at least brave or proactive or strong—and we create several layers of justification to prove to ourselves that we are not bad people. (And if we are mean, we’re only mean to people who have it coming anyway!)

For that reason, much of evil group behavior is motivated by goals that sound noble: progress; purity; heritage; revenge for a legitimate past wrong; whatâs only fair. The problem surfaces when these virtues, real or imagined, take precedence over morality and ethical treatment of others. The subtler the swap is, the more people will fall for it. Fear of authority can also motivate people to go along with evil behavior or at least turn a blind eye to abuses. And once someoneâs gotten in too far and realized theyâve crossed a moral line, they may be unwilling to admit it and turn back.

A villain group should have an understandable perspective—probably not enough to excuse their cruelty or war crimes, but something we can at least grasp. Maybe itâs even something we can relate to in an uncomfortable way, forcing us to re-examine our own viewpoints.

Donât underestimate the power of a well-told story

If all of these pitfalls make worldbuilding sound too complicated, take heart: the point is not to create a world that actually could be real, but one that feels real in the context of excellent storytelling.

For example, the Harry Potter universe definitely feels very real to millions of fans across the globe. But even J.K. Rowling has let slip some inconsistencies that make you scratch your head if you think about them—such as how can the entire wizarding community function when everyone has only a fifth-grade education in mathematics, writing, and other Muggle subjects? Are there really enough jobs at the Ministry of Magic and whimsical broom shops for all those Hogwarts graduates? And why would they give the ability to time-travel to a thirteen-year-old girl but never use it again?

But you never really ask these questions during the course of the novels, because Rowling is such a good storyteller that these more technical questions never occur to you. We are fully engaged in the moment, and the dream stays intact.

A writer doesnât have to be perfect in their worldbuilding, just careful. If the rest of the world is well-developed and the plot is compelling enough, it hides the occasional (and unavoidable) gaps. The audience stays solidly within the dream that the writer weaves, never noticing that in a few places, if you pull back the curtain, you can see the puppet-strings.

Main photo courtesy of David Marcu. Ice photo courtesy of Sergey Pesterev.

Bio:

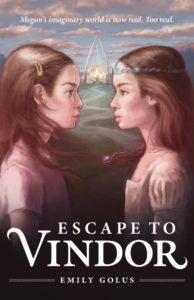

Emily Golus has been dreaming up worlds since before she could write her name. A New England transplant now living in the Deep South, Golus is fascinated by culture and the way it shapes how individuals see the world around them. Her fantasy works are filled with diverse and complex people who are unwillingly united in times of great danger.

Emily Golus has been dreaming up worlds since before she could write her name. A New England transplant now living in the Deep South, Golus is fascinated by culture and the way it shapes how individuals see the world around them. Her fantasy works are filled with diverse and complex people who are unwillingly united in times of great danger.

Golus aims to write stories that engage, inspire, and reassure readers that the small choices of everyday life matter. In addition to her first two fantasy novels, Escape to Vindor (winner of the 2018 Selah Award) and its upcoming sequel, she writes about world-building and what it truly means to be a storymaker. Explore her fantasy creations at WorldofVindor.com, and read her blog at EmilyGolusBooks.com.

Golus aims to write stories that engage, inspire, and reassure readers that the small choices of everyday life matter. In addition to her first two fantasy novels, Escape to Vindor (winner of the 2018 Selah Award) and its upcoming sequel, she writes about world-building and what it truly means to be a storymaker. Explore her fantasy creations at WorldofVindor.com, and read her blog at EmilyGolusBooks.com.

You can also find her on Instagram and on Facebook. In addition, you can read an introduction and excerpt to Golus’s award-winning debut novel, Escape to Vindor, posted in an earlier Spec Faith Fiction Friday article.

Iâll admit, being a fantasy writer has sucked some of the fun out of enjoying pop culture. For example, hereâs what happened after watching the famous âLet It Goâ sequence from Disneyâs Frozen:

Iâll admit, being a fantasy writer has sucked some of the fun out of enjoying pop culture. For example, hereâs what happened after watching the famous âLet It Goâ sequence from Disneyâs Frozen:

Emily Golus has been dreaming up worlds since before she could write her name. A New England transplant now living in the Deep South, Golus is fascinated by culture and the way it shapes how individuals see the world around them. Her fantasy works are filled with diverse and complex people who are unwillingly united in times of great danger.

Emily Golus has been dreaming up worlds since before she could write her name. A New England transplant now living in the Deep South, Golus is fascinated by culture and the way it shapes how individuals see the world around them. Her fantasy works are filled with diverse and complex people who are unwillingly united in times of great danger. Golus aims to write stories that engage, inspire, and reassure readers that the small choices of everyday life matter. In addition to her first two fantasy novels, Escape to Vindor (winner of the 2018 Selah Award) and its upcoming sequel, she writes about world-building and what it truly means to be a storymaker. Explore her fantasy creations at

Golus aims to write stories that engage, inspire, and reassure readers that the small choices of everyday life matter. In addition to her first two fantasy novels, Escape to Vindor (winner of the 2018 Selah Award) and its upcoming sequel, she writes about world-building and what it truly means to be a storymaker. Explore her fantasy creations at

This was not my first reaction to I Can Only Imagine, by the way. Though the movie has some of the corniness typical of Christian films, I was moved by the basic story of a son separated from his father and rebuilding that relationship with him, of a father turning to God, and a song partially inspired by that relationship. Though part of the reason that story resonated with me so strongly is my father drank. My father beat me severely only once, but he was recklessly dangerous for a child to be around apart from anything he did directly (I lost a finger as a child under his supposed supervision of wood cutting). He also was often absent while my parents were married and after their divorce, years would pass by without me hearing from him.

This was not my first reaction to I Can Only Imagine, by the way. Though the movie has some of the corniness typical of Christian films, I was moved by the basic story of a son separated from his father and rebuilding that relationship with him, of a father turning to God, and a song partially inspired by that relationship. Though part of the reason that story resonated with me so strongly is my father drank. My father beat me severely only once, but he was recklessly dangerous for a child to be around apart from anything he did directly (I lost a finger as a child under his supposed supervision of wood cutting). He also was often absent while my parents were married and after their divorce, years would pass by without me hearing from him.

In a discussion of imagination and world creation, CS Lewis aptly stated that âno merely physical strangeness or merely spatial distance will realize that idea of otherness which we are always trying to grasp in a story about voyaging through space: you must go into another dimension. To construct plausible and moving âother worldsâ you must draw on the only real âother worldâ we know, that of the spirit.â

In a discussion of imagination and world creation, CS Lewis aptly stated that âno merely physical strangeness or merely spatial distance will realize that idea of otherness which we are always trying to grasp in a story about voyaging through space: you must go into another dimension. To construct plausible and moving âother worldsâ you must draw on the only real âother worldâ we know, that of the spirit.â

thousands. Clans, tribes, kinship groups: all have been societies unto themselves, holding political power and social organization within a web of kinship. Common ancestry, real or invented, is an effective way of forging identity and unity, and a tenacious one. Even today, ethnic violence is often a reversion to tribal divisions, whose bonds prove stronger than overlying national identities.

thousands. Clans, tribes, kinship groups: all have been societies unto themselves, holding political power and social organization within a web of kinship. Common ancestry, real or invented, is an effective way of forging identity and unity, and a tenacious one. Even today, ethnic violence is often a reversion to tribal divisions, whose bonds prove stronger than overlying national identities.