This post is a dive into a pool of Biblical ideas that at first may not seem to have much to do with speculative fiction. But it really does–if you read or write speculative fiction that features gods and goddesses, demons and devils, magic and spiritualists. What does the Bible say about these things?

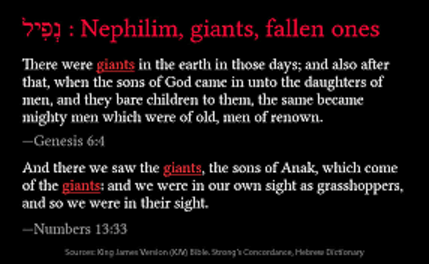

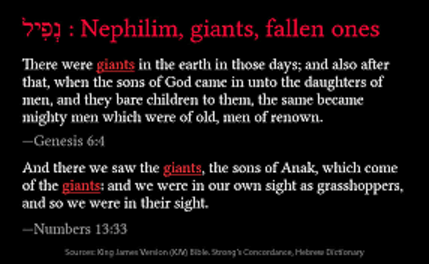

My particular inspiration for this article is a comment my friend Mike Duran made on Facebook (I plan on sharing a link to this article with him). He quoted Dr. Michael Heiser, who in short is saying that demons are the spirits of slain Nephilim referenced in Genesis 6 (and the extra-Biblical book of Enoch). Though I could take the tactic of directly addressing both what Heiser says and why he says it (I believe it has quite a lot to do with his education in ancient Mesopotamian mythology), instead, let me give an overview of what the Bible says about demons–or more broadly, about spirits in opposition to God, whatever we choose to name those spirits. This is something I’ve talked about before, on my own blog, but I’ll do it in a different way here than I’ve done in the past.

Take a favorite Bible translation you have in computer format (or break open your Strong’s Unabridged if you enjoy massive papery tomes) and do a search for the word “gods.” You should be aware up front that not every translation will agree how many times the word appears in the Bible. This has to do not only with some difference in texts, but with the nature of the Hebrew word “Elohim” (××××××) which is a plural word mostly used with single verbs, which is usually applied to the God of Israel, but arguably could apply to other gods as well. Christians traditionally have explained this plural/singular as hinting at the Trinity, while Jews talk of a “plural of majesty,” and the folks who educated Dr. Heiser say the term points to a past when the Hebrews were polytheists–of course such scholars say the Hebrews evolved into monotheists over time (they say so because God is fictional in their minds and therefore could not have revealed his unique nature to Moses or to anybody else) and so “Elohim” referred to the “council of the gods” that Hebrews once believed in because some of their Pagan neighbors had similar ideas. (Which Heiser accepts as a true concept, but gives it a Christian twist.)

Don’t get lost in such minutia right now. I want you to notice something else here, broad observations. First, in the Old Testament there are loads of references to gods in the plural who in context are specifically not the God of Israel. And there very few such references in the New Testament. Quite a number of gods are mentioned by name prior to the New Testament, Ba’al and Asherah only being the top two.

If you skim through the references to “gods,” you’ll see that the gods mentioned in the Old Testament are not said to be fictional at any point. Especially at first, they are simply mentioned in terms of gods you shall not worship–worship is reserved for Jehovah alone. A bit later Scripture says that their idols are worthless, unable to speak, to hear, or to move. They are specifically stated not to have been the creators of the universe, in contrast to Jehovah (Jer. 10:11). But never, not once, does the Old Testament plainly state that there really only is one God and all the rest are fictional (the closest it gets is in saying God is the “God of gods” which could imply other gods are or were subservient to him as angels or several other possible interpretations). Yes, you can plainly see that Israel was only to worship one God, that the rest are weak posers in comparison to God (that only Jehovah is responsible for creation, for example), and that idolatry is idiotic. But that isn’t the same as “the gods are fictional.”

So if that’s true, if the gods are real and are genuine rivals to Jehovah (you won’t see much in terms of kindly tolerance of worship of other gods in the Old Testament) what happened to the gods in between the Old and New Testaments? Why are they mentioned so much in the OT and very little in the NT? What did they do, go on vacation or something?

To answer that, do a different search. Two different ones, actually. First, search for “demon.” Again, it depends on what Bible translation you use, but you’ll see that there are either no references to demons in the Hebrew Scriptures (a.k.a. Old Testament) or just a few of them, in contrast to a pile of them in the Greek Scriptures (the NT). Likewise, “devil” will show you quite a lot in from the Greek Scriptures but little from the Hebrew.

When you search for “devil,” translations vary–the King James made them all references to “demons” into “devils”– but you will find references to a singular devil (Devil with a big “D”) in other translations and at least in the KJV references to plural “devils.” But you won’t find many or any of these in the OT, just in the NT.

Hmmm. Could the gods and demons/devils be the same thing, just under different names? That idea would certainly explain where the gods went (they just got renamed), but isn’t satisfactory in other ways. We don’t hear of people being possessed by the gods in the OT, yet, demons do a whole lot of possessing and oppressing people in the NT.

Do yet another search. Search for “spirits” (as opposed to “Spirit” in the singular). You’ll find a pile of references that cross over, finally, both Hebrew and Greek Scriptures. In the OT you will see commands forbidding seeking out spirits and references to unclean spirits and the New Testament essentially has the same references, with different emphasis–again, much more on possession than the Hebrew Scriptures ever mention. But still, it’s pretty evident the terminology is similar.

Now try searching for “Satan.” You’ll find that a few Old Testament references exist, ones that some people claim are totally different than who we think of as being Satan today–they say Satan is the “opposer” who presents himself with the other divine beings/angels/sons of God (depending on your interpretation) in the book of Job. But, however, excuse me, ahem, if we are to take the New Testament as coming from God (and if we don’t, we run into real problems considering ourselves Christians) the NT plainly affirms that Satan is the Devil and is the serpent as well (yeah, that serpent, the one in Genesis 3)–please refer to Revelation 12:9.

OK, so the Devil in the singular is Satan according to the Bible, who is talked about quite a bit in the New Testament, and a little bit in the Old Testament, significantly as the tempter of Adam and Eve.

Also, please notice that Satan (a.k.a. “the Dragon”) is said to have angels fighting with him in Revelation 12:7, just a hair away from where I just quoted. It doesn’t matter that the battle in Revelation takes place after the beginning of time. The passage plainly identifies Satan as having his own angels. Not his own Nephilim or half-angels.

If you don’t find Revelation 12:7-9 noteworthy here, please remember that Christian tradition through the centuries also, with little disagreement, agrees that the Devil = Satan = the serpent of Eden. And that Satan was accompanied by a host of (fallen) angels.

Please notice that if we see Satan in Genesis 3, that means he existed before Genesis 6. So Satan is not a product of the rebellion of that happened at that time. Satan certainly seems to be of the same substance of the demons that possess people, since Luke 22:3 states Satan directly possessed Judas Iscariot. And if the big D-devil (Satan) existed prior to Genesis 6, why is it that the angels that follow him would not exist until after that? Hmmm.

I suppose it’s possible that spirits of dead Nephilim added themselves to the body of demons or affiliated with them in some sort of way, but the Devil and the angels who follow him (a.k.a. demons), who surely existed prior to Genesis 6, are more than enough to explain all demonic activity, without reference to Nephilim.

Now, it is true that we don’t really have specifics as to when or why Satan rebelled and took “his angels” (that’s me quoting the Bible there) with him. The traditional interpretations of Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28 referring to Lucifer/Satan have been widely challenged and for once, for reasons that actually make sense (though I think the traditional view of those passages has some value, I agree that people have good reasons to disagree). So we essentially have no solid Biblical information about Satan’s rebellion and the angels he took with him, though it clearly it happened and it clearly happened prior to Genesis 3.

Note also that one OT passage that contains both the term “devil” (in the KJV) and “gods” and equates them–“devils” (or demons) are “gods!” (Deut 32:17) And note also that one of the few New Testament references to “gods” equates them with demons as well, saying things sacrificed to idols are sacrificed to demons (I Cor. 10:20).

So if we are going to take the Bible seriously, it seems the case is closed on where the gods went–the ancient gods are in fact demons. As to why they acted differently in New Testament times, I’m not sure, but another look at the Old Testament might clear things up a bit.

What exactly is the difference in the Old Testament between worshiping gods other than God and calling up spirits anyway? Doesn’t calling up spirits seems like a different sort of thing–and also, doesn’t it sound like it relates to the New Testament term “unclean spirit” (a.k.a. “demon”)?

But actually, there isn’t much difference between calling up spirits and calling on gods in the OT. Both things are forbidden in Israelite worship, both things are seen as substitutes for seeking God, and both things involve seeking spiritual forces. There is an actual difference in that going to meet the gods at a temple site might (perhaps) be a classier affair than consulting a spiritualist in the dead of night. But really, at the temple of the gods, the ancient Pagans expected to communicate with their gods via priests and priestesses. Whereas a medium might call up someone more “familiar” (heh heh)–a friend or relative. But both the work of the spiritualist and the work of the temple priests were considered “magic” under the Old Testament law, both were forbidden, and both were seen as substituting something else for what properly belongs to Jehovah (see Isaiah 8:19 concerning spiritualists).

And that realization, that the Pagan spiritualists and the Pagan temple worshipers were actually doing essentially the same thing in a different context gives light to why magic is forbidden in the Old Testament. Because as that term was used in the Bible, it always meant seeking spiritual power other than God.

It’s like a form of treason.

The gods of Olympus, by Giulio Romano

This fact is part of the reason why I object relatively little or not at all to stories that contain magic without any specific cause linked to it, like Harry Potter. While I do object to, say, Percy Jackson, in which the gods are characters in the story and the protagonist is a demigod. It’s the inclusion of other gods and Pagan rituals seeking power outside of God that was the dividing line for the Old Testament and is a dividing line for me as well. Not the use of power per se.

So why would the Bible care about that? What’s the big deal about seeking gods (/spirits/demons)?

It’s because the gods are not fictional–oh, specific myths about them are fiction, but there is a genuine spiritual power behind the host of Pagan deities that exist and have existed. They have not gone on vacation, either, though they have interacted with humanity in different ways over time in accordance with our own belief systems.

They seem more than happy to reappear in our culture in the guise of gods yet again–if you haven’t heard, modern Neo-Pagan religions are growing dramatically. And in fact, references to gods in fiction also seem to be growing more and more common.

So what happened to all the gods?

Nothing. They are still around. Following our culture as it changes, willing to act demonic if need be, but looking for opportunities to be worshiped once again…

also afterwardâwhen the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown.â The Nephilim are mentioned once more, as the terrifying inhabitants of Canaan (in reality, the ancestors of the prodigiously-sized Anakites; whether they have any connection with such groups as the Rephaites is more than I can say).

also afterwardâwhen the sons of God went to the daughters of men and had children by them. They were the heroes of old, men of renown.â The Nephilim are mentioned once more, as the terrifying inhabitants of Canaan (in reality, the ancestors of the prodigiously-sized Anakites; whether they have any connection with such groups as the Rephaites is more than I can say).

While I’d love to toot my publisher’s horn, I want to focus on this nebulous term “edgy Christian fiction” and what it means today compared to what it meant just a few years ago. When one hears the term “edgy,” it usually means “hip” or “cool” or “trendy.” People often correlate “edgy” with “cutting edge,” the latest, most fashionable thing in this or that industry.

While I’d love to toot my publisher’s horn, I want to focus on this nebulous term “edgy Christian fiction” and what it means today compared to what it meant just a few years ago. When one hears the term “edgy,” it usually means “hip” or “cool” or “trendy.” People often correlate “edgy” with “cutting edge,” the latest, most fashionable thing in this or that industry.