So for those of us who just enjoy reading great stories (even better if theyâre fantastical), and donât keep up with all the bookmaking politics, hereâs the scoop.

Apparently the Christian Booksellers Association, or CBA, is getting a shakeup.

The case

Agent Steve Laube, a friend of SpecFaith (and Christian fantasy fans anywhere), first noted this yesterday:

Key staff people in CBA (aka Christian Booksellers Association) are no longer working for the association. In what appears to be a purge, Curtis Riskey, president for 11 years, is no longer working there.

Laube noted that CBA had not announced any transition or put out a press release.

Then Publishers Weekly did some checking and discovered this:

[Dallas-based entrepreneur Edward] Roush is drastically reorganizing the CBAâs staff and services in order to âbuild a trade association that is strong enough to meaningfully help the industry,â according to Deborah Mash, president of CBA Media, a subsidiary of CBA Service Corporation.

“CBA has been a poorly managed debt machine for many years, so Mr. Roushâs efforts to restructure the organization were imperative and unfortunately indicative of many of the problems in the industry as a whole,” Mash said in an email to PW.

Important comical fact: the outgoing president of the CBAâs last name is âRiskey.â

More important fact: the Christian Booksellers Association is long-running professional group that helps member Christian bookstores trade goods, including movies and books.â The CBA was formed in 1950. And lately itâs been struggling, like any business based on physical stores and traditional publishing in the 2010s.

Many news stories and blogs about failing regular bookstores, however, seem to lament the Passing of an Era. Theyâll take shots at Amazon.com, or write clickbait-type articles with titles like âMillennials Are Ruining Mayonnaise and the Library.â

Yet with the Christian book industry, I wonder if some Christians could care less.

The charge

Hereâs what I mean. When I see news about the CBA struggling or about a bookstore chain closing, or one agentâs 2017 predictions of market shrinking, the loudest reaction isnât much like regret. If anything, a lot of people seem to gloat.

Narrowing this to books and then again to fiction books: If the news (rightly or wrongly) comes outââChristian fiction is dyingââand people say, basically âGood riddance,â this arouses my suspicion. I want to know if they had any involvement with this potential crime. I want to put on my best outrageous Hercule Poirot mustache, adopt some hybrid Euro-accent, and drag in folks for questioning.

The suspects

So. Christian fiction appears to be dying. Where were you on the night of X?

âI was watching the latest prestige streaming drama on Netflix,â says the youthful Christian collegian and/or sort-of-hipster academic type. âCritics were really raving about this one. But I donât read Christian fiction. Didnât know it wellâother than the fact that it is corny, sentimental, and bound by silly conservative rules.â

Really. Were you aware that (1) a service like Netflix started out offering abysmal streaming fare, which is an inevitable stage of a new media sourceâs early growth? (2) plenty of Christian fiction, with labels, content restrictions, and all, is actually awesome?

âWell, I just donât prefer that mass-market Christian stuff no oneâs ever heard of. Iâd rather see TV shows that are esoteric and indie, which everyoneâs talking about.â

So. Christian fiction appears to be dying. Where were you on the night of X?

ââChristian fictionâ?â guffaws a Millennial. âThat still a thing? I read some when I was a kid. But it has all those rules. People in those books canât even cuss! Let âem die.â

Stop to consider, my friend, that every medium has its own content restrictions, either as a matter of good taste or service to most of its diverse audience. Sure, on YouTube you can say the F-bomb all you like. But try dropping the N-bomb; itâll blow up in your face.

â[Bomb] that. Reality isnât real unless people are cussing. Iâm all about really real reality with real things. Which means in the real world, everyone cusses all the time.â

So. Christian fiction appears to be dying. Where were you on the night of X?

âI left that behindâget it?âalong with the conservative nonsense that ignores the Bibleâs call to justice,â says the sober young activist Christian ministry leader. âChristian fiction does not actually help us connect with our neighbors. I prefer to engage secular fiction that helps me connect with them.â

So, the purpose of fiction is solely to help us evangelize people? Some Christian fiction also assumes that. You agree? You just think it doesnât evangelize effectively?

âKeep talking. Iâd like to write a blog about how Christian culture is just the worst.â

So. Christian fiction appears to be dying. Where were you on the night of X?

ââChristian ⌠fiction?ââ says the middle-aged mother. âOh. I only read Christian nonfiction about important things. Like about how thereâs actually a secret code about the United States hidden in the book of Isaiah. Or about how small children actually take routine trips to paradise, and unlike the apostle Paul, are permitted to tell what they saw. Or about how Iâm the hero of my own story, girl.â

Would you like to answer further questions with your attorney so you can avoid a possible future charge of perjury? You clearly stated you do not read âChristian fiction,â then proceeded to give several of your favorite examples of the same.

âAm I being detained? If not, then I must go. Iâm late for my fellowship group about the new nonfiction book, Jesus Calling to Heaven is for Real So Wash Your Face.â

So. Christian fiction appears to be dying. Where were you on the night of X?

âChristian fiction,â sniffs the young conservative whippersnapper sort-of Calvinist preacher. âSo weâre talking about that now? I havenât been to a Christian bookstore in years. Itâs full of not only terrible heresy but ridiculous kitsch. The music is carnal. The books are worse. They keep all the important, thick, historic theology books on the back shelf! In the very front they put out only the ridiculous stories for women and children. Itâs all just fiction. All make-believe entertainment. Sure, thatâs fine and maybe thereâs nothing wrong with itâmaybeâbut in a world where the so-called churches are constantly compromising with the truth, we donât need fantasy. We donât need stories. We need Godâs word. And by âGodâs word,â I mean preaching. Only preaching! Like the kind that I do. And like some of my friends do. Meanwhile, all these shallow people who claim to follow the gospel but instead get all distracted by this popular-culture nonsense and think that they can âexegeteâ the world instead of expositing theââ

Sir. I doused you with truth serum when you werenât looking. Who is your audience?

âMy ⌠audience?â

Yes. In your own imaginary world: who listens to you? Real people? Real people who like fiction? People could really benefit in their heads and their hearts from active, creative, Â thoughtful, excellent Christian fictionâthe kind you refuse to support even in theory?

âN ⌠no.â

No what?

âNo, thatâs not my audience.â

Whoâs your imaginary audience, then?

âOther young pastors. Only other young pastors.â

Yep, we really need to scoff at that escapist, non-real-world fiction stuff.

âAnd only people who have the same personality as me, who only prefer nonfiction and doctrine and podcasts about preaching. Say, do you have any more of this truth serum? It’s quite relaxing. Being a young conservative whippersnapper sort-of Calvinist preacher is hard.â

I can imagine it is. (muttering to self) But it may go easier if you didnât spend all your free time blogging against heresies.

âHm? What’s that?”

Nothing.

“How could I ⌠relax? Take a Sabbath rest ⌠that would be really nice âŚâ

As if God didnât make humans to work seven days a week? To spend all our time teaching and evangelizing and whacking heretics? As if we actually do all those important things in anticipation of a day when we rest and enjoy adventures on New Earth under Jesus, our creator and King of all good imagination? Then here. Try this Christian novel.

brave, beautiful heroine. Its attraction is enormous, but a curious pattern emerges among the re-tellings. Even while staying faithful to the facts of the story, many re-tellings shift the dramatic and emotional center from Esther and Mordecai to Esther and Xerxes. The story of Esther is commonly told as a romance, but in the Bible, the relationship that matters most is the one between Esther and Mordecai.

brave, beautiful heroine. Its attraction is enormous, but a curious pattern emerges among the re-tellings. Even while staying faithful to the facts of the story, many re-tellings shift the dramatic and emotional center from Esther and Mordecai to Esther and Xerxes. The story of Esther is commonly told as a romance, but in the Bible, the relationship that matters most is the one between Esther and Mordecai.

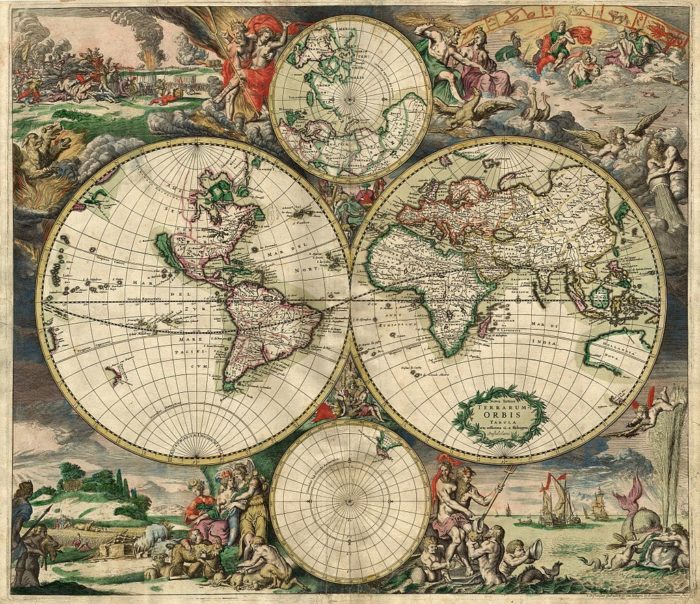

I think those elements and themes are universal, so I want to say speculative fiction is for everyone. But I wonder. Are the day-to-day conditions for people not living in a first world country perhaps too close to the pretend conditions of our speculative fiction. I mean, many don’t have to imagine a government depicted in dystopian, or war shown in epic fantasy or ostracism or alienation portrayed in a science fiction. They live with despotic governments, the dangers of war, unfair treatment based on ethnicity. Why read speculative fiction if you only have to look out your window to see the clash of good and evil.

I think those elements and themes are universal, so I want to say speculative fiction is for everyone. But I wonder. Are the day-to-day conditions for people not living in a first world country perhaps too close to the pretend conditions of our speculative fiction. I mean, many don’t have to imagine a government depicted in dystopian, or war shown in epic fantasy or ostracism or alienation portrayed in a science fiction. They live with despotic governments, the dangers of war, unfair treatment based on ethnicity. Why read speculative fiction if you only have to look out your window to see the clash of good and evil. I have to wonder about that position. I mean, as many have pointed out before, Jesus told stories. The Bible is filled with stories. And at least on two occasions someone in Scripture told a story that would have to be identified as speculative. The Bible, remember, was not originally written to first world cultures. Jesus didn’t come and live during the internet era, or during the industrial revolution.

I have to wonder about that position. I mean, as many have pointed out before, Jesus told stories. The Bible is filled with stories. And at least on two occasions someone in Scripture told a story that would have to be identified as speculative. The Bible, remember, was not originally written to first world cultures. Jesus didn’t come and live during the internet era, or during the industrial revolution.

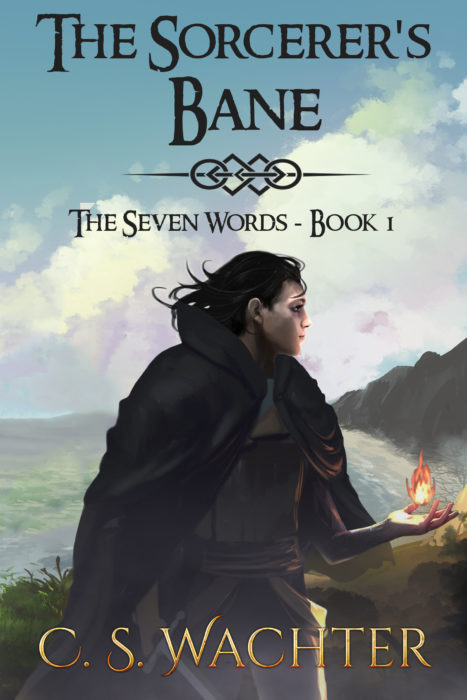

This week we feature C. S. Wachter and her novel

This week we feature C. S. Wachter and her novel

I know there are some stories that feature the prince or the warrior or the soothsayer. There are some centered around the dragon keeper (a nod in particular to Donita Paul and her DragonKeeper Chronicles); still others feature the assassin. These, of course, are professions, and there is a certain amount of work connected to what they do.

I know there are some stories that feature the prince or the warrior or the soothsayer. There are some centered around the dragon keeper (a nod in particular to Donita Paul and her DragonKeeper Chronicles); still others feature the assassin. These, of course, are professions, and there is a certain amount of work connected to what they do. Star Trek, the original, included the same elements, (though, of course, the worker red shirts are inevitably the ones who die in a crisis). The spin-off series maintained that same bit of worldbuilding. Miles was the transporter chief and his wife a botanist. Deanna Troi was the ship’s counselor and Beverly Crusher, the chief medical officer.

Star Trek, the original, included the same elements, (though, of course, the worker red shirts are inevitably the ones who die in a crisis). The spin-off series maintained that same bit of worldbuilding. Miles was the transporter chief and his wife a botanist. Deanna Troi was the ship’s counselor and Beverly Crusher, the chief medical officer. Jill Williamson’s By Darkness Hid opens with the protagonist getting up early to feed the animals. It was his job as a slave. However, he quickly advances to become a squire, and off he goes on his quest.

Jill Williamson’s By Darkness Hid opens with the protagonist getting up early to feed the animals. It was his job as a slave. However, he quickly advances to become a squire, and off he goes on his quest.

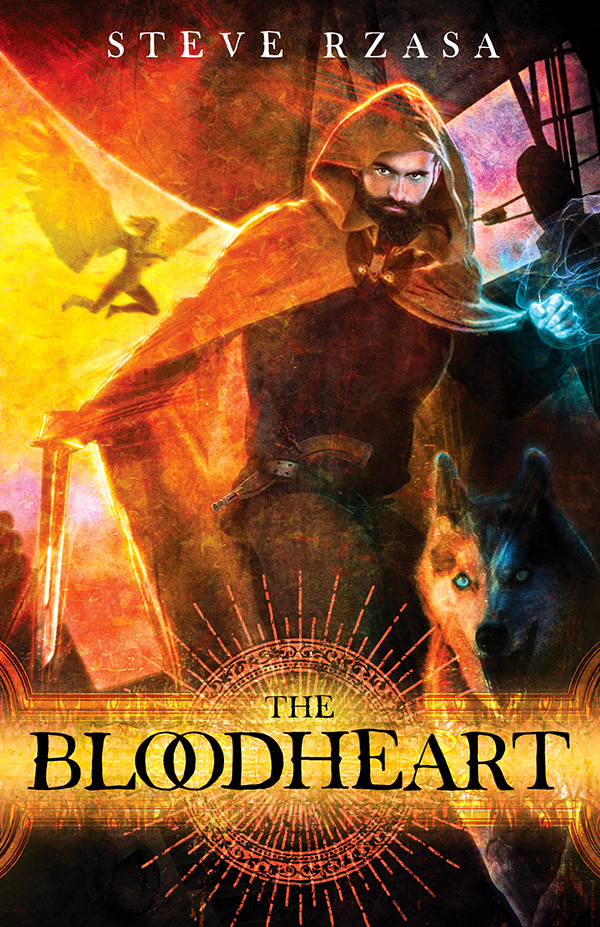

This week we feature Steve Rzasa and his novels

This week we feature Steve Rzasa and his novels

My characters in stories like The Face of the Deep series or the Vincent Chen novellas are Christians who are familiar with persecution. They interact every day with those who do not believe, so theological discussions take place. They read Scripture and go to church or, in the case of the Rescue Ops crew in Broken Sight, have chaplainâs services aboard their starship light-years from Earth.

My characters in stories like The Face of the Deep series or the Vincent Chen novellas are Christians who are familiar with persecution. They interact every day with those who do not believe, so theological discussions take place. They read Scripture and go to church or, in the case of the Rescue Ops crew in Broken Sight, have chaplainâs services aboard their starship light-years from Earth.