Four professing Christian men, in the Christian writing industry, have been accused of committing abuse of power to different degrees.

Two of them have been previously named and featured here on Speculative Faith.

Publishers Weeklyâs website proclaimed the story last week, although women have already been carefully sharing these accounts around Christian writing and conference circles for years.

It should matter to us where these stories come from. It matters that any man, professing to be a Christian, has been accused of this kind of behavior. It matters that any person who associates his name with Jesus Christ (the literal meaning of Christ-ian is âChristlike personâ) also has his name associated with these evils.

(Sensitivity alert: itâs necessary to describe these acts to understand them.)

- Physical sexual assault

- Begging women for sex

- Proposing sexual hookups by email

- Soliciting sex in exchange for career favors

- Lying and covering up these abuses of power

- Insisting that patterns of abuse are not typical or no big deal.

Just as the torrent of accusations against abusive leaders in entertainment call for prophetic Christian engagement, so do accusations against âour ownâ people require serious attention. And serious consequences. And serious challenge to ourselves, to determine what, if anything, we can do to glorify God, protect victims, and challenge any person who is tempted to abuse his power in creative industries.

Iâve written twelve doâ and donâtâstyle ideas about how Christians may respond to claims of abuse. Part two will release Monday, and part three will release Tuesday.

Note that although these may apply to the articleâs specific situations, Iâm thinking in general terms about how Christians respond to claims of abuse committed by other Christians. But first, some personal housekeeping:

- First, these accusations affect victims of abuse and harassment. Set aside all the doctrinal or professional factors. Real people, mostly women, have gone through a lot to tell their stories. Iâve asked several of them, along with Lorehaven magazine staff and supporters, to give early feedback on this article. They might also arrive here to comment. They might share the article and repeat part of their stories. Take great care and courtesy in response to their openness.

- These accusations affect Speculative Faith. As I stated above, some of the men mentioned have written articles at Speculative Faith. At this point, we wonât take down the articles (see my sixth response in part 2). No oneâs made such a call of us. But, itâs worth noting that if we could have known these individuals were accused of this behavior, we would have, at minimum, declined to publish.

- These accusations affect our spinoff magazine, Lorehaven. Last fall, based on early and partial knowledge about these accusations, we changed the leadership of Lorehaven. Iâm now the sole publisher and editor-in-chief of this web magazine, which aims to help Christian fans find truth in fantastic stories.

With that in mind, letâs explore twelve Christian responses to accusations like these.

1. Listen to abuse victims.

This should go without saying. A lot of this should. But often a Christian who learns of these accusations behaves just like the naĂŻve Christian who hurls a quote of Romans 8:28 in the direction of the grieving parent who just lost her baby in a car wreck. âWell, âall things work together for good âŚâ!â

With the greatest possible respect: these folks must shut up.

Listen to the victim. If this isnât someone you know in person, but whose words you are reading in an article or social media comment, pay attention to her account. Donât talk. Just listen. You can work through your responses later. If you donât yet believe her, maybe because you know or respect the person being accused, maybe you can say, âI listened to what you said and Iâm so sorry you are hurting. Iâm thinking about it and Iâm also praying for you.â Thatâs it.

2. Donât respond with these lines.

Every time I think maybe weâve gotten past this nonsense, I see new examples of it:

âWhy is it always about sex?â

My answer: Nonsense. Itâs not about abuse of sex. Itâs about abuse of power. (If it were about sex, he can get that just by going to the internet and watching porn.)

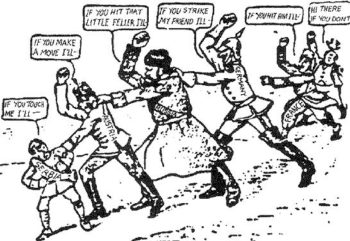

Itâs not just social science that supports this claim. So does the Bible. All sin comes from our abuse of power. Itâs our failure, going all the way back to Genesis 3, to steward our gifts and role as God our Creator intended. Thatâs idolatry. And itâs pride. Pride, which C. S. Lewis called âthe utmost evil,â is an abuse of power.

âWow, but he never did that sort of thing to me!â

My answer: Congratulations. No, really. It sounds like God protected you by some means, either because you were not that personâs âtypeâ or because you were not vulnerable in this area. Very often, abusers target women who already struggle with poor self-image, or depression, or previous abuse, or thoughts of suicide.

Target, groom, push, defend, push more, suggest itâs her idea, lather, rinse, repeat.

If youâre strong, use your strength to support that vulnerable woman. As a Christian who is emotionally or spiritually strong in a particular area, that is your sober duty.

âWell, the way women dress these days âŚâ

I actually saw someone say this. Itâs an old and bad notion. It brings to mind the disciplesâ mechanical cause/effect view in John 9:2 of âsomeoneâs sin always causes human suffering.â This is not a thing godly Christians say to people suffering abuse, any more than we would say, âWell, he should have been buckled inâ to the parent of a child killed in a car accident. That argument presumes there is something to the notion of âladies who dress modestly wonât be sexually harassed.â If I had space here, Iâd fiercely contest that notion also. Itâs false, and fails to account for a manâs responsibility.

âNone of us are perfect.â

Repetitions of this confuse me. At best, theyâre awkward attempts to change the topic, and redirect to safer, thousand-foot views of general âmistakesâ and human âbrokennessâ rather than specific acts of human evil. At worst, theyâre an attempt to ignore these potent and terrifying biblical truths: that each of us is guilty of sin, and sin brings Godâs judgment and damnation to Hell, and sometimes we must confront specific sins against specific people and make tough decisions how to respond. That goes triple when the power-abusers will, if unchecked, hurt even more people.

âNone of us are perfect (so whatâs for dinner?)â is not how Jesus replied when facing specific instances of power abuse, or the reality of sin in every human heart.

âMaybe she started it.â

This utterly fails to take into account the power dynamics of the relationship: pastor/church member, mentor/conference newbie, publisher or agent/writer. In any relationship like this, itâs the leader who is more accountable, not the follower.

âIf men and women could just avoid each other âŚâ

This is often called âThe Mike Pence Rule,â although the concept was first associated with Billy Graham and Iâd prefer the late evangelist keep it. In certain contexts, such as those involving a fearful or spiritually weak man, avoiding one-on-one meetings might be wise. But at best this is a remedial solution, not an ultimate solution.

The Bible talks about treating âolder women as mothers, and younger women as sisters, with absolute purityâ (1 Timothy 5:2, NIV). It does not encourage us to avoid one another based on fear, and does not lay out a Billy Graham/Mike Pence rule.

Now, in my case, I have spent lots of time in virtual âone-on-oneâ rooms, with several women, preparing this very article. In my editorial roles at Speculative Faith and Lorehaven, I simply must do thatâitâs my job and itâs their job! However, my wife and I also have guidelines in place for similar purposes as the Rule. She has my passwords, and we frequently talk about the results of these discussions. Thus, in a world thatâs confused and fearful about how the heck men and women can avoid nonsense while also getting things done and respecting/loving one another as spiritual family, we can take precautions while not going overboard.

âYouâre forgiven, [name of accused].â

Itâs not our place to say this. Literally, this is like saying, âMan, your sins are forgiven youâ (Luke 5:20). When even the Pharisees have better theologyâthat God alone can forgive Person Aâs sins against Person B (Luke 5:21)âweâre in trouble.

Nor is it our place to flock first to an accused personâs defense to assure him of Godâs love and forgiveness (now or in the future). This presumes far too much about the accused personâthat he is (1) already saddled with enough guilt as it is, (2) caught up with his real repentance to the victim (or usually, a group of victims), (3) a member of a local church that has begun a biblical process of rebuking and restoring him (1 Cor. 5), (4) is already hearing from some imaginary force of nasty Bad Cop Christians that heâs a terrible, terrible sinner, freeing us up to be the Good Cops, (5) an actual member of Christâs body and therefore included in the warnings and promises of those who share our faithâa fact we technically cannot prove or disprove based merely on a long-distance or professional relationship with him.

Thatâs a lot to presume, especially over the internet. So letâs not presume that.

3. Reconsider whether victims must forgive the accused.

Here I must be very careful, and acknowledge that early feedback to this article included hearty disagreement with this concept. Iâll choose to proceed this way.

When Christian A accuses Christian B of abuse, others often give two responses.

Response One (Vengeance) says, âWhat an evil person. Never forgive him.â Some Christians may imply that the accused is outside Godâs grace, or will go to Hell. (Pagansâor Christians who behave like pagansâdo even worse then they gather and say things like, âLetâs ruin his career and send him death threats over Twitter.â)

Response Two (Cheap Grace) says, âYou need to forgive him immediately. Then you act like the sin never happened, because âlove keeps no record of wrongs,â and also, âJesus said to forgive anyone seventy times seven.â To do otherwise denies grace.â

I suggest that both these responses show extreme notions of cheap condemnation or cheap grace, and both fail to capture the complexity of the biblical picture.

Further complicating the picture is this: Christians often use the word âforgivenessâ as a shorthand to describe several biblical concepts. These include the concepts of (1) fighting the urge to become bitter or resentful, (2) fighting the urge to slander and take revenge on the offender, (3) reflecting that God in his grace has saved us from the chiefmost offense of prideful idolatry against him, (4) overlooking the offense of a brotherâmeaning someone (perhaps a family member) in otherwise good relationship with us, who has a besetting sin that heâs already fighting, (5) leaving the offense to God (Romans 12:19) and trusting him to avenge the wrong.

Here is a hard yet biblical saying: If victims of sinful abuse donât want anything to do with these biblical ideas, then theyâre in the wrong. They must consider âforgivingâ this abuse, and healing to a point of wanting to offer this forgiveness. There is no room for the Christian to harbor resentment and choose the way of vengeance, either against an abusive nonbeliever or a believer who falls into abusiveness.

Therefore, insisting âIâll never forgive himâ is not an option for the Christian. People who have stated this may fall to the Dark Side very quickly. According to Jesus, they imperil their own claim to live in light of Godâs forgiveness of them (Matt. 6: 14â15).

Recommended in case you have ever needed to ask or give forgiveness.

However, I do not believe that Christians should use the word âforgivenessâ to refer to this biblical choice of rejecting vengeance and only wanting to forgive offenders. I donât say this only because the word âforgiveâ has been used so often, along with â⌠and forget,â to silence victims and make them feel terrible for being wounded. I say this because biblically, the word forgiveness describes, as Chris Brauns says:

a commitment by the offended to pardon graciously the repentant from moral liability and to be reconciled to that person, although not all consequences are necessarily eliminated.

Among Christians, this real forgiveness is always a mutual arrangement between offender and victim. And it will always leads to actual reconciliation, if not in the present day, then in the future after Jesus has returned to make all things new.

Scripture, however, never calls us to âforgiveâ a person who has not repented.

This does not contradict Christâs insistence that we forgive our brothers âseventy-seven times,â that is, offering unlimited forgiveness. (Most recall Christâs words from Matt. 18: 21â22, but see the parallel text in Luke 17: 3â4, in which itâs clear Jesus is talking about situations in which the offending brother is first offering repentance.)

Nor does this contradict the Bibleâs assuranceâwhich many Christians believeâthat any Christian is eternally secure. Godâs word assures us that âno one can snatchâ someone out of Christâs hand (John 10: 28â29). Yes, thatâs true, and yet we cannot ignore biblical warnings such as âNo one born of God makes a practice of sinningâ (1 John 3: 8â9). The Bible also teaches that real faith will inevitably show the fruit of good works (Eph. 2: 8â10), and that people who have âtasted the heavenly giftâ can fall away (Hebrews 6: 4â8). Such warnings are part of the way God corrects and preserves his people, and cheap grace would get in the way of that.

In fact, this is affirmed by the very biblical teaching that God himself does not forgive people who do not repent. Hell is not full of forgiven people who simply refused to repent after God forgave them. (The very fact that Jesus said the Father will not forgive people who donât forgive [Matt. 6: 14â15] shows that God does not forgive everyoneâand that no Christian is outside Godâs warnings about holiness.)

This is also affirmed by biblical teachings that reflect human frustration with power-abusers who get away with it. See the imprecatory Psalms, or Revelation 6:10:

They cried out with a loud voice, âO Sovereign Lord, holy and true, how long before you will judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?â

Yes, Scripture calls on us to be willing to forgive and to love our enemies. But loving enemies does not mean we gloss over their pattern of offenses against others, or even ourselves. By Godâs standards (and often by the civil-law standards of our own regions, which I havenât even touched on in this piece) we must confront the behavior. And if the person does not repent, we cannot (yet) properly forgive him.

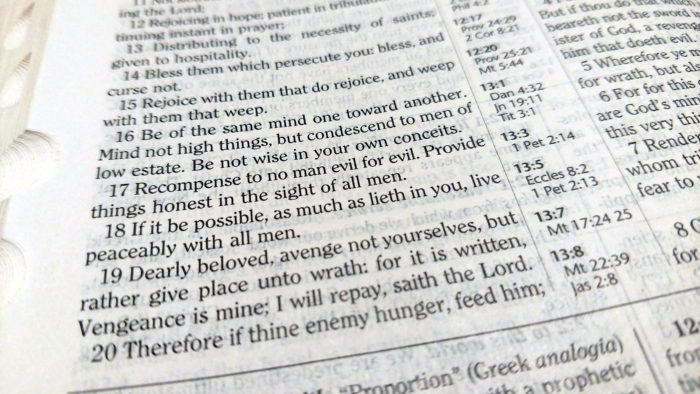

Every time I contend for this view, someone presumes Iâm automatically excusing grudges or bitterness, or justifying the person who abuses this truth to withhold a willingness to forgive an enemy. Not so. Iâm simply saying we ought to use words properly, as God does. And God has given us a great phrase to use for what we mean by âletting go of the offense.â Instead of the word forgiveness (which, again, means an exchange between two willing parties), Paul says leave it. But finish the apostle Paulâs sentence: âLeave it to the wrath of Godâ (Romans 12:19). He does not say this is merely a feeling, or even a personal choice. He says this is based on the entirely practical truth that we trust God as the avenger. If your enemy is a Christian who refused to repent, God will discipline him. If your enemy turns out to have been a fake Christian, God will avenge the wrong and punish this enemy for eternity.

“Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord” (Romans 12:19, KJV).

If Iâve been abused, I ought to want to forgive the abuser as soon as possible. But this is not simply a case of offense between brothers, spouses, or church members. Instead, this is a case of egregious sin, when one professing Christian for years has shown a pattern of acting more like the devil than like a true follower of Jesus.

At the very least, such a person needs to demonstrate true willingness to repent, which will require facing consequences (including potential loss of leadership positions and careers). The rewards, however, will be great indeed. He will have received real forgiveness (all the better if itâs nearly instant) from the persons he has wronged. That pattern of sin will no longer interfere with his relationship with God and claim to faith.

In any case, victims of abuse, and those who love them, must cling to the gospel, in which Jesus forgives people who repent. Donât let people imply you must be more spiritual than God. But pray hard and train hard so you can forgive the offender as soon as possible. Meanwhile, try to leave itâthe offenseâto God, and find healing not through fake âforgivenessâ but because you know the chief Avenger.

4. Donât make judgments about salvation.

Two very difficult facts arise when weâre talking about professing Christians who are reputably accused of patterns of bad behavior like this: (1) that real Christians do terrible things, up to and including acts of fornication and abuse of power, (2) that God is the final judge of a personâs faith and pardoner of his sins.

Thatâs highly inconvenient for us. It means that we donât get to decide who is and is not a legitimate Christian (now or future) because it is ultimately Godâs place to judge. It means that we live in light of perfect future justice that may not take place until eternity. It might mean that we end up letting the guilty âgo freeâ in this age, or might end up spreading untruths about an accused person. God will sort it all out. He will uncover all nasty truths weâve hidden and fix all the lovely lies weâve spread.

Knowing this, we deal with accusations as best we can, in the various settings to which weâre calledâwhich includes local churches and other Christian groups.

On Monday, weâll explore four more responses to abuse accusations, and how Christians might address ethics and abuse reports in churches versus other organizations, such as Christian writersâ conferences.

This week we feature Christopher D. Schmitz and his novel Wolf of the Tesseract in Lorehaven Book Clubs. Stop by the flagship book club on Facebook to learn more about these stories.

This week we feature Randall Allen Dunn and his novel The Red Rider in

This week we feature Randall Allen Dunn and his novel The Red Rider in

Contests can help, no doubt. When a book wins an award at

Contests can help, no doubt. When a book wins an award at  So here’s what I’m asking. Have you read any speculative fiction in 2018? If so, what book or books? How would you rate them? If they are titles you could recommend, pass them along to us. And then put that same recommendation somewhere else on the internet. Maybe write a review for Amazon or B&N, mention it in a group on FB, put up a review on your blog. You know, anywhere that other readers might see what you think about this good book.

So here’s what I’m asking. Have you read any speculative fiction in 2018? If so, what book or books? How would you rate them? If they are titles you could recommend, pass them along to us. And then put that same recommendation somewhere else on the internet. Maybe write a review for Amazon or B&N, mention it in a group on FB, put up a review on your blog. You know, anywhere that other readers might see what you think about this good book.

This week we feature Aidan Russell and his novel

This week we feature Aidan Russell and his novel

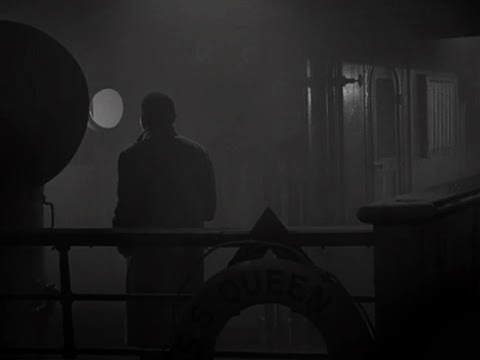

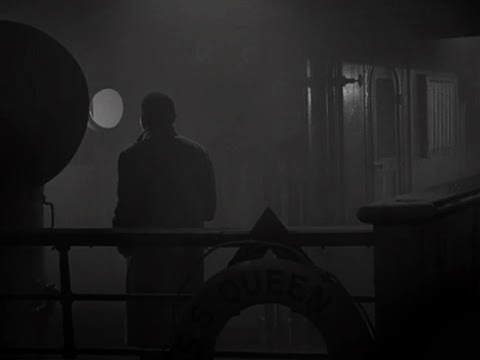

where people carry on civil conversation despite the silent, hanging dread of being stalked by German U-boats. Our protagonist is the most afraid of all, and with reason: he cannot remember getting on the ship, knows nothing but his name and birthplace and an awful sense of familiarity coupled with a crippling dread. âJudgement Nightâ follows the Twilight Zone pattern â tiresome elsewhere, but not here â of a bewildered person growing more and more distraught until he finally understands the trap snapping over him.

where people carry on civil conversation despite the silent, hanging dread of being stalked by German U-boats. Our protagonist is the most afraid of all, and with reason: he cannot remember getting on the ship, knows nothing but his name and birthplace and an awful sense of familiarity coupled with a crippling dread. âJudgement Nightâ follows the Twilight Zone pattern â tiresome elsewhere, but not here â of a bewildered person growing more and more distraught until he finally understands the trap snapping over him.