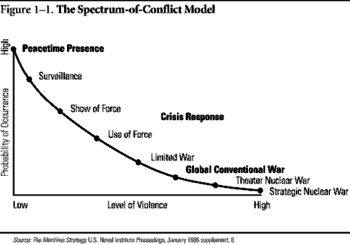

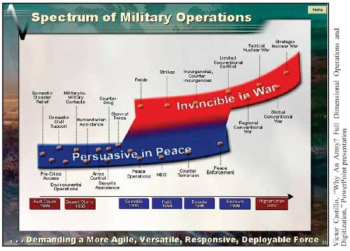

Travis P here. Last time we talked about levels of war (tactical, operational, and strategic) and mentioned a number of different types of war (siege, aerial bombing campaigns, etc). This time weâre looking at something called âSpectrum of Conflict.â In my experience working with engineers, they like diagrams and images. Travis Chapman is no exception, established by the fact heâs provided three diagrams of the concept weâre discussing! To which Iâm actually adding one image I found on my own, the first one below, because I feel it gets across well why the word âspectrumâ gets used for this military topic (from Heritage.org):

Credit: Heritage.org

Just like a spectrum of light has a variety of shades of color, warfare can come across as a spectrum of activities that nations can perform, just like the diagram I just used shows. To make sure everyone understands the concept, let me use the Cold War as an example:

The United States and the Soviet Union, for approximately forty-five years, assumed roles as global adversaries. The two nations each had a section of divided Berlin, each had masses of troops in its own version of Germany (and Korea, though that also involved the Chinese). Each had strategic nuclear weapons capable of killing the majority of the human race, competing with one another as to who would have the most such weapons. Each had a global navy and an active competition in outer space; each extensively spied on one another; each supported revolutions in other nations (often with covert action); and each engaged in smaller wars on the periphery of areas they controlled, with the other side supporting the opposition–in Vietnam and Afghanistan in particular. The closest they ever got to direct war was when Soviet âadvisorsâ to the North Koreans were actually flying MIG jets that US pilots (in South Korea under a United Nations mandate) engaged in aerial combat.

Most Cold War war activities would be in the âgray zoneâ of the diagram Iâve shared. Some covert actions would get into the âirregularâ zone of covert operations. âHybrid warâ Iâll talk about in a bit…and a âlimited conventional warâ is what the USA might call our war in Vietnam. No âtheater conventional warâ (as in, all of Asia, i.e., a theater) happened during the Cold War.

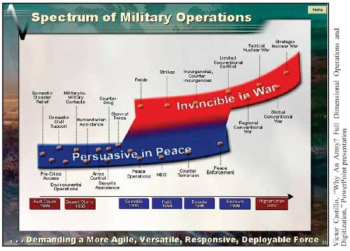

Credit: The Maritime Strategy, U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 1986, via Sam Tangredi at Air University

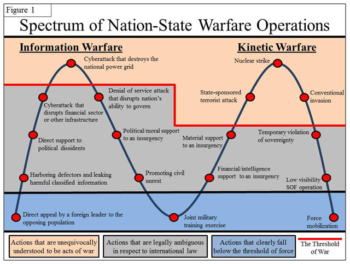

Let me show another diagram (from Air University) that helps illustrate how two modern countries have a variety of possible responses to one another. Note the axis of probability on the vertical versus the violence axis on the horizontal, which shows that under modern-day conditions, less violent actions are more likely to be a nationâs first response over more violent ones:

The reason this is the case for major modern nations (note the chart tops off at âStrategic Nuclear Warâ) is because the entire dynamic of national interactions is different when strategic weapons are around, since we really donât want to blow ourselves up. If we diagrammed Genghis Khanâs spectrum of conflict, it might have only have two points on it–âcall on foes to surrenderâ or âinvade.â (Ahem.) Though even though modern nations generally have more options, most nations over most of the worldâs history have had a variety of actions they could take against other nations. These include such things as a trade embargo or denial of access to strategic areas (like closing off the Soviet fleetâs access to the Mediterranean in the Cold War).

But the two charts Iâve shared so far still donât fully account for all the possible actions that can be a part of war’s spectrum. Here’s another:

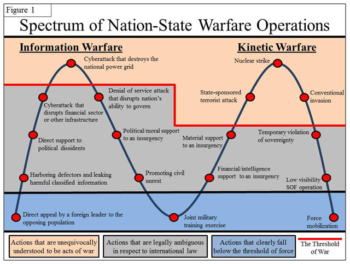

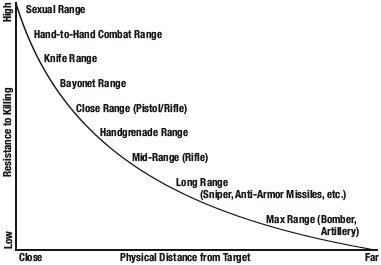

Credit: Victor Castillo, “Why An Army? Full Dimensional Operations and Digitization” from On Point.

Whatâs nice about this chart (from On Point)Â is it shows a wide variety of activities modern nations can engage in–and in all of which the military has a role to some degree–peacetime roles being as important as wartime. (The chart even color codes recent military conflicts according to âredâ or âblueâ action.)

Modern U.S. Army doctrine (âUnified Land Operations,â ADP 3-0) looks at the spectrum of conflict a bit differently. It says all forms of warfare consist of three things, offense, defense, and âstability operationsâ (which means activities a military performs when not in direct combat to maintain peace). Itâs a bit like mentioning a television uses three primary colors in various mixtures to create every shade of color you see. Though whether or not these three colors cover all possibilities is perhaps debatable–for example, the Art of War extensively talks about offense and defense but also mentions peace negotiations as an element of war (Sun Tzu, The Art of War, Ch. 3, 17).

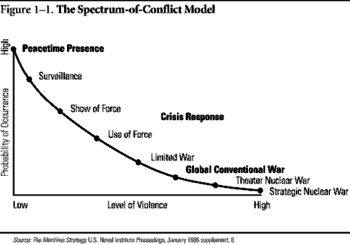

Credit: Jason Rivera at Small Wars Journal

Letâs share one more diagram, because it will help me illustrate âhybrid war,â something I said Iâd talk about but havenât yet (from Small Wars Journal):

The point of this oscillating diagram isnât to talk about hybrid war, itâs to demonstrate that modern nations can and do perform actions that perhaps have hostile intent, but which fall short of war–and also clearly perform acts of war–and also do some things that lie in-between. While this chart is geared towards modern nations, the principle of different actions performed at various levels of hostility would apply to most nations found in speculative fiction.

But letâs look at some of the elements that are very modern on this chart. Like cyberwarfare. Or a nation sponsoring a terrorist attack. These are elements of âhybrid warfare,â which is quite a modern idea. Itâs the everything-including-the kitchen-sink approach. Russia has used variations of hybrid warfare against Georgia and Ukraine–they messed with elections, knocked out electric power, crashed key servers with cyberattacks, shut down the airwaves, put military personnel in civilian clothes and had them conduct strikes (that would seem to be terrorist attacks), funded actual insurgents, and followed up with conventional military attacks. In other words, they did as much damage as possible while maintaining plausible deniability of their involvement, which had the effect of increasing the effectiveness of their regular military when they rolled in.

Futuristic science fiction stories should include hybrid warfare as something that nations (or planets) would at least know about, if not perform. But while these ideas are modern and arenât likely to be going away, letâs not rule out fantasy worlds having their own versions of hybrid warfare. Because story worlds that include the practice of magic could have lots of nasty ways to strike out at an enemy covertly while maintaining plausible deniability. Though of course, not everyone would want to fight a hybrid war, even if they could.

Remember what I said above about Genghis Khan as a bit of joke? (and whatâs not funny about a brutal invasion? Hey...just kidding) Where I said heâd have only two possible actions? That example shows that nations are not just shaped by their technology, what they are capable of doing, but by their culture, what theyâre interested in doing. And it gives a speculative fiction writer some room to be creative with alien and demi-human or magical races. Aliens or demi-humans etc. might have very different ideas about what is and is not legitimately part of a war (or peace) than humans have–and what methods can be considered âfair gameâ in war. And obviously if that race even wants to play fair. Which is something worth considering when thinking about your aliens/demi-humans/magical creatures.

Travis C here: Hopefully itâs clear that when you hear âwarâ it could mean almost anything. If you are an author, you will need to define what you mean and try to stay consistent. If you are a reader, youâre already mentally doing the analysis to figure out âWhat exactly is going on?â and hoping the author gives you enough detail to draw a conclusion. Even with a sweeping multipart epic like Game of Thrones or The Stormlight Archive, itâs challenging for an author to paint the entire spectrum from peaceful military-to-military training all the way through âNo, really, this is the end!â Armageddon-esque battles.

As an example of a spectrum of conflict at work, Iâd like to use a softball: J.R.R. Tolkienâs world of Middle Earth. Tolkienâs writings are extensive and provide sufficient material to draw from, but for those who havenât enjoyed the pleasure of The Silmarillion, Iâll draw from the Peter Jackson envisioned story as told in each trilogy: The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit (or as I call it, âA Movie About a Book I Once Read Called The Hobbit That I Canât Remember That Well But Thought Would Be Cool In Three MoviesâŚâ) I digress…

Letâs look at the easy side first: Everyone Not Mordor.

What’s this ranger doing Bree? Peacekeeping operations? (Credit: New Line Cinema)

Middle Earth in The Hobbit and early in The Fellowship of the Ring displays many evidences of what weâd consider pre-crisis activities. There is âa shadow growing in the Eastâ, but many people are getting along with their lives just fine. Tolkienâs vision of the Shire is perfect in this regard. What brewing conflict? More importantly, Iâve got to get these garden plots taken care ofâŚ

Through seemingly miraculous means, the good people of Middle Earth unite against the orcs of Angmar and goblins of the Misty Mountains. Some of these forces are clearly prepared for combat (elves & dwarves), and given their long lives they have experience on their side, so weâll assume thereâs some active training happening in the background. The humans of Lake Town appear disorganized yet motivated to defend their own, having suffered the consequence of fighting against Smaug those many years ago.

Fast forward to The Fellowship of the Ring. We see several former allies acting as nations might during a time of peace that anticipates future conflict. As we leave the Battle of the Five Armies, we have an agitated group of elves all intent on vacating Middle Earth (well, many of them). The dwarves have withdrawn to their strongholds. Yet each of the major kingdoms of men realize conflict is coming.

Garrisoned at Osgiliath, Faramirâs efforts to secure the border between Gondor and Mordor have failed. Border security has morphed into a limited war on the Pelennor. (Credit: New Line Cinema)

The most obvious is Gondor. We see evidence that Gondor, more than any other nation, has experienced a progression from the low intensity end of the spectrum. What were initially peacekeeping operations across the river from Osgiliath have now become border defense. Orc raids test the defenses and consume Gondorâs waning resources and attention. Military-to-military ties with Rohan have been broken due to a classic case of âWhere were you whenâŚâ Lord Faramirâs efforts to hold Osgiliath, and his brother Boromir’s actions before that, have clearly escalated from peacekeeping and surveillance of the enemy to shows of force (i.e., having troops garrisoned at the ford) and limited engagements.

As the story progresses we see Gondorâs posture change from light defense to besieged, fully recognizing that Sauronâs timeline for a campaign is much shorter than the Steward anticipated. In the opening battle of the campaign, Sauronâs forces rout the garrison at Osgiliath, then fully circumvallate Gondor. Itâs only through active intervention by unexpected allies that Gondor is saved as full-scale combat operations break open on the Pelennor Fields outside Minas Tirith.

We saw a similar situation in The Two Towers, as Rohanâs roving horse warriors, the Rohirrim, react to increasing threats to their borders by orc raids. As Ăomer (and his cousin before him) try to press King Theoden to escalate their actions, he is met with resistance and ultimately must chose exile to maintain a semblance of border protection. This quickly progresses to the siege at Helmâs Deep and the quick deployment of Rohanâs army to support Gondor.

Now letâs change places to the less-easy, but beautiful, examples of conflict spectrum provided by Isengard and Mordor.

In The Fellowship of the Ring, we witness the rise of Isengard as Saruman extends his influence and schemes in concert with Mordor. As his tower Orthanc becomes a seat of military power we watch, quite truly, the shaping of Isengardâs forces and resources as Saruman prepares to leave diplomacy and scheming behind and embark upon a conventional war against his enemies. Orc raids, seen in Fellowship, extend into Rohan. Human allies are sought and brought into his armies in what weâd call coalition operations. An information campaign aids Saruman in winning discontented men to his side, and he wields his most effective weapon, Wormtongue, against the only significant threat in the region. Once Theoden is free from his prison, the clock winds down to the Battle of Helmâs Deep and the retaking of Isengard by the Ents.

What we donât see in The Two Towers is a progressive escalation up to the conventional battle. We know Isengard has been active, but itâs not shown on the screen (and not significantly developed in the book). In my opinion, thatâs alright. Tolkien was trying to tell a different story that one of a military escalation of force. Yet, we have seen similar events in our own time, when a nation throws the majority of its eggs in one basket and embarks on a military objective knowing that, if successful, their single credible threat would be eliminated long enough to secure the ultimate purposes of the nation. The risk of failure doesnât outweigh the value of success. Would that Saruman might have sent his forces elsewhere.

Lastly, we have Mordor. Iâd like to go back in time a bit though, and letâs think of how we arrived here. Sauron crafted the Ring and its kin. Nine kings gave their kingdoms and lives in service to Mordor. Thatâs a powerful alliance. Mordorâs strength, while thrown back in the Battle of Dagorlad (the opening sequence to The Fellowship of the Ring), continued to grow in its protected realm.

Sauron observing the Battle of Dagorlad from Mordor, an example of a limited war escalating into a theater war against a combined army of allies. (Credit: LOTR Wikia)

Then we witness the stirring of Sauron as he puts a new plan into motion. The dragon Smaug is tempted to align his strength with Mordor (at least in the cinematic interpretation). The Nine are found again and given back their fell powers. Orcs and goblins have joined forces against men, elves, and the scattered dwarves.

By the time Frodo and Sam enter the picture, we have an active Mordor pressing the borders of Gondor. Sauronâs emissaries have successfully brought Umbar and the Easterlings into alliance. With forces moving in the open, we witness Mordor showing its strength to any who would see.

By The Two Towers we watch Sauronâs campaign against Gondor unfold, going from raids and strikes to a persistent attack against Osgiliath, to the opening movements that signal at least a limited war (taking Osgiliath as a foothold) and ultimately the Battle of Pelennor Fields (Gondor) and later, the Battle of the Morannon (Battle of the Black Gates) when Sauron is overthrown.

Whew.

Hopefully youâve seen a few examples in the canon of Tolkien to quench our literary thirst. Certainly we could make our analysis even deeper, but space limits us here. Tolkien created a world where war escalated quickly yet contained many elements of a spectrum of conflict. Another example might be Brandon Sandersonâs The Stormlight Archive, where we enter a world already deep into a protracted war, with flashbacks that help the reader understand how it reached that stage, with clear progression of military actions, as well as brilliant examples of hybrid warfare that involves information and public opinion among the participants. .

I also hope weâve piqued your interest in the subject. It was always a favorite of mine in my strategy & war classes. I recommend searching for âspectrum of conflictâ to see other examples that may be helpful in how you plan your next book or series with war as a key element. Now back to those X-Y plots and charts Iâve got brewing….

happen and people who do not exist. We all know how real fiction can be, and how stories can accompany us through life, following us through changes that leave old times and old friends behind. Depending upon the time and manner of their entrance into our lives, stories acquire associations with larger things â a carefree summer, a person we knew then, old haunts, even (a thousand Star Wars jokes donât change the truth) a gone childhood. To touch the story is to touch hidden chords.

happen and people who do not exist. We all know how real fiction can be, and how stories can accompany us through life, following us through changes that leave old times and old friends behind. Depending upon the time and manner of their entrance into our lives, stories acquire associations with larger things â a carefree summer, a person we knew then, old haunts, even (a thousand Star Wars jokes donât change the truth) a gone childhood. To touch the story is to touch hidden chords.

Itâs about method

Itâs about method Example 1: In Star Wars, we see several leaders within the Empire react to the power of the Death Star. They see it only as a tool to bend others to their will, and never react to the decimation it causes when leveled against a planet.

Example 1: In Star Wars, we see several leaders within the Empire react to the power of the Death Star. They see it only as a tool to bend others to their will, and never react to the decimation it causes when leveled against a planet. Many readers may be familiar with Brandon Sandersonâs Stormlight Archive. It follows a small cast of characters as they navigate a world on the brink of destruction from ancient powers, all while humanity is fighting amongst itself for power and supremacy. Enter Dalinar Kholin, brother of the king, Brightlord, and Highprince of War of the Alethi armies. He has received visions and knowledge of an ancient path known as The Way of Kings, a code of honor that he attempts to resurrect among the factious Alethi. His son, Adolin, doesnât quite get it, but is strongly influenced by his father. This part of the plot is in stark contrast to Brightlord Sadeas, who basically represents everything we would ever hate about a person (selfish, backstabbing, conniving, spiteful, basically awful in every way).

Many readers may be familiar with Brandon Sandersonâs Stormlight Archive. It follows a small cast of characters as they navigate a world on the brink of destruction from ancient powers, all while humanity is fighting amongst itself for power and supremacy. Enter Dalinar Kholin, brother of the king, Brightlord, and Highprince of War of the Alethi armies. He has received visions and knowledge of an ancient path known as The Way of Kings, a code of honor that he attempts to resurrect among the factious Alethi. His son, Adolin, doesnât quite get it, but is strongly influenced by his father. This part of the plot is in stark contrast to Brightlord Sadeas, who basically represents everything we would ever hate about a person (selfish, backstabbing, conniving, spiteful, basically awful in every way). âI will go up to the six-fingered man and say, âHello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.â

âI will go up to the six-fingered man and say, âHello. My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.â

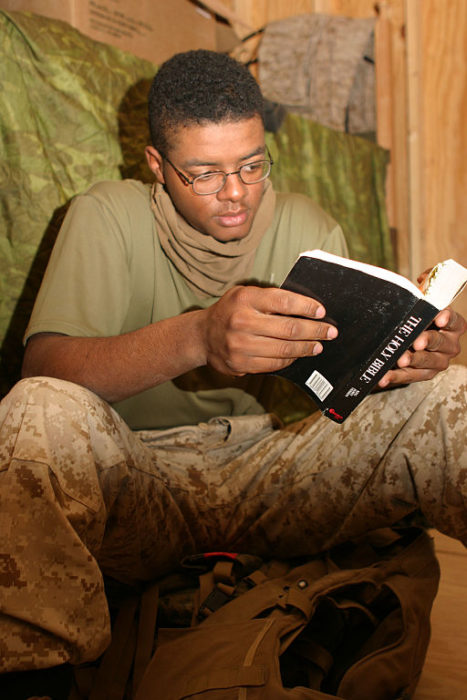

Perhaps the most common use of the Bible is the imaginative use of Biblical characters—demons, angels, the Nephilim. In fact, there are so many books in this category that the genre “Supernatural suspense” has come into being. Here are a few examples. Tosca Lee’s debut novel, which launched her fiction, was Demon: A Memoir. Karen Hancock wrote a science fiction-ish novel that incorporated the Nephilim. Shannon Dittemore wrote her Angel Eyes YA series, featuring very Biblical angels and demons. Kathryn Mackel wrote Hidden, an eerie story about chained fallen angels who break free.

Perhaps the most common use of the Bible is the imaginative use of Biblical characters—demons, angels, the Nephilim. In fact, there are so many books in this category that the genre “Supernatural suspense” has come into being. Here are a few examples. Tosca Lee’s debut novel, which launched her fiction, was Demon: A Memoir. Karen Hancock wrote a science fiction-ish novel that incorporated the Nephilim. Shannon Dittemore wrote her Angel Eyes YA series, featuring very Biblical angels and demons. Kathryn Mackel wrote Hidden, an eerie story about chained fallen angels who break free. I know of a few true allegories in the vein of Pilgrim’s Progress that have recently seen publication. One such is Walter Cantrell’s Disciple’s Quest series. In these books, the author puts Scripture in his own words from time to time, and also uses verses taken from the King James Version.

I know of a few true allegories in the vein of Pilgrim’s Progress that have recently seen publication. One such is Walter Cantrell’s Disciple’s Quest series. In these books, the author puts Scripture in his own words from time to time, and also uses verses taken from the King James Version.

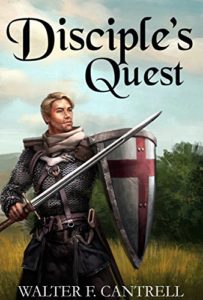

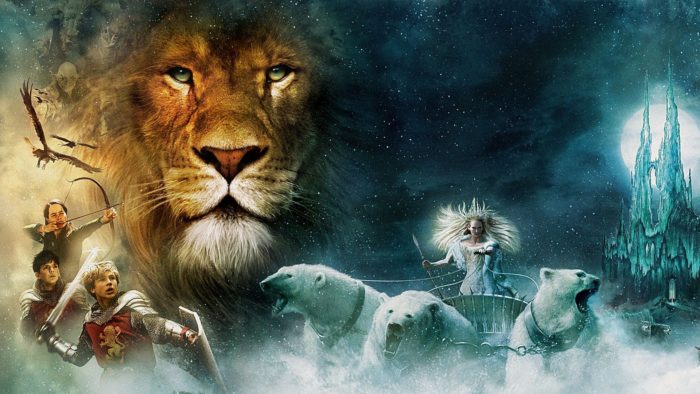

Who among you loved The Voyage of the Dawn Treader film? Yes, I see those three hands. The film itself sunk. But Will Poulter as Eustace Clarence Scrubb totally deserved this role. (And a better story.) Alas, by now eight years have passed, and Poulter is too old to return to the magical land of Narnia.

Who among you loved The Voyage of the Dawn Treader film? Yes, I see those three hands. The film itself sunk. But Will Poulter as Eustace Clarence Scrubb totally deserved this role. (And a better story.) Alas, by now eight years have passed, and Poulter is too old to return to the magical land of Narnia.

As an author of speculative fiction, I find myself wondering, where is Ben Kenobi? Where is Gandalf? Where are the wise mentors with the power to make a difference, as well as the willingness to sacrifice themselves in defense of the helpless? If writers abandon such archetypal figures, what will be the consequence?

As an author of speculative fiction, I find myself wondering, where is Ben Kenobi? Where is Gandalf? Where are the wise mentors with the power to make a difference, as well as the willingness to sacrifice themselves in defense of the helpless? If writers abandon such archetypal figures, what will be the consequence? Certainly, there are adults who misuse their power to manipulate, control, and abuse. But the idea that everyone is a user with ulterior motives does nothing to help those young people who live under such tyranny every day. What they really need is the reassurance that there are people who can and will come to their rescue. Instead, we have offered them the cynicism of despair.

Certainly, there are adults who misuse their power to manipulate, control, and abuse. But the idea that everyone is a user with ulterior motives does nothing to help those young people who live under such tyranny every day. What they really need is the reassurance that there are people who can and will come to their rescue. Instead, we have offered them the cynicism of despair. Rebecca D. Bruner is the author of six books, including Welcome, Earthborn Brother, a YA science fiction novel from Splashdown Books, My Fairy Godfather, a collection of short stories, and The Pre-Med and the Frog Prince, a twisted fairy tale. Her non-fiction book, A Wife of Valor: Your Strategic Importance in God’s Battle Plan, was a finalist in the Excellence in Editing Award competition in 2017. Rebecca has two grown children who make her very proud. She lives in Arizona with her husband and two cats. Connect with her online at her

Rebecca D. Bruner is the author of six books, including Welcome, Earthborn Brother, a YA science fiction novel from Splashdown Books, My Fairy Godfather, a collection of short stories, and The Pre-Med and the Frog Prince, a twisted fairy tale. Her non-fiction book, A Wife of Valor: Your Strategic Importance in God’s Battle Plan, was a finalist in the Excellence in Editing Award competition in 2017. Rebecca has two grown children who make her very proud. She lives in Arizona with her husband and two cats. Connect with her online at her