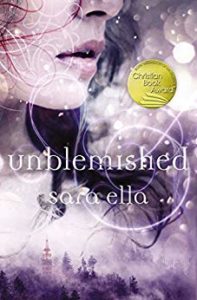

Fiction Friday: Unblemished By Sara Ella

Unblemished

by Sara Ella

INTRODUCTION—Unblemished

Unblemished is the first in the Unblemished Trilogy. Book 2, Unraveling, is a finalist in the 2018 Christy Awards, Young Adult category.

âA breathtaking fantasy set in an extraordinary fairy-tale world, with deceptive twists and an addictively adorable cast who are illusory to the end. Just when I thought Iâd figured each out, Sara Ella sent me for another ride. A wholly original story, Unblemished begins as a sweet melody and quickly becomes an anthem of the heart. And Iâm singing my soul out. Fans of Once Upon a Time and Julie Kagawa, brace yourselves.â âMary Weber, award-winning author of the Storm Siren Trilogy

Eliyana canât bear to look at her own reflection. But what if that were only one Reflectionâone world? What if another world exists where her blemish could become her strength?

Eliyana is used to the shadows. With a birthmark covering half her face, she just hopes to graduate high school unscathed. That is, until Joshua hops a fence and changes her perspective. No one, aside from her mother, has ever treated her like he does: normal. Maybe even beautiful. Because of Joshua, Eliyana finally begins to believe she could be loved.

But one night her mother doesnât come home, and thatâs when everything gets weird. Now Joshua is her new, and rather reluctant, legal Guardian. Add a hooded stalker and a Central Park battle to the mix and youâve gone from weird to otherworldly.

Eliyana soon finds herself in a world much larger and more complicated than sheâs ever known. A world enslaved by a powerful and vile man. And Eliyana holds the answer to defeating him. How can an ordinary girl, a blemished girl, become a savior when she canât even save herself?

UNBLEMISHED — EXCERPT

It canât be true. Iâve known the news for a week, and still it hits me as if Iâm finding out for the very first time.

It canât be true. Iâve known the news for a week, and still it hits me as if Iâm finding out for the very first time.

Elizabeth Ember, Up-and-Coming Artist of the Upper West side, Dies at 34.

The bold headline on the front of the New York Times obituaries blares up at me, a black and white photo of Mom posted beneath. Was it only last month this exact photo adorned another section of the paper? Even with gray skin, her dark hair swept into a messy bun, Momâs organic beauty radiates from the page. Why she hated being photographed, Iâll never understand. I flip the paper upside down. When I die, will my portrait grace the news?

Of course not. My face looks as if a toddler scribbled on it with a red Sharpie while I was asleep. No reporter in his right mind would put my picture in the paper. Not unless it was a Halloween edition.

Mom used to sit in the rooftop garden of our brownstone, a cup of hot Earl Grey in her hands, and gaze out over Manhattan. She adored this city for its energy and symphony of cultures. âItâs always alive, always moving,â sheâd said.

Now, every consolation from a complete stranger invites a fresh wave of sobs. My chest heaves with each one, rising and falling like the steady tumult of the Hudson on a stormy day. I drive back the waves with smiles and nods and deep, controlled breaths, all for the sake of appearances. To be the hostess Mom wouldâve been. The one Iâll never be.

âIâm so sorry for your loss . . .â

Smile.

âSheâll be missed . . .â

Nod.

âIt will be better with time . . .â

Inhale.

âYou know weâre all here for you, dear . . .â

Exhale.

Nothing more than empty words from phony people who canât even look me in the eye as they give their condolences. Can I blame them? I donât enjoy looking at me. Why should they?

My phone vibrates, dancing along the granite countertop in our—my kitchen. The screen lights up, flashing the name and selfie that hurts and comforts in one ping of mixed emotions.

Joshua.

My fingers curl around the orchid-colored case, squeeze. I asked him to stay away, to give me space. Time. He agreed with a solemn ot, giving me what I wanted.

If itâs what I wanted, why do I long to go next door and fall into his arms?

I close my eyes, mentally pushing away the cacophony of voices echoing around our—my home. It doesnât work. This is all just too much.

A sea of catered dishes covers the kitchen island. Nothing offers comfort like platters of prosciutto and tartlets, right? What is this, a cocktail party? And could it be more obvious these people know nothing about me or Mm? Prosciutto? Really? Gag me. I havenât touched meat in ten years, and Iâm certainly not going to start now.

Beyond the bar, the sunroom with its large bay window, upright piano, ornate fireplace is set up as an art gallery. Momâs recently commissioned dealer, Lincoln Cooper, took care of all the details, despite the setback his recent gallery fire caused him. How very noble of him considering heâs known us less than a month. Where did he find all these people? Do they even know who theyâre mourning, or are their sympathies part of the show?

Easels display oil-pastel renderings and watercolor paintings along with a few of Momâs charcoal sketches. Most of the pieces featured are from her Autumn collection. Lincolnâs idea of staying on theme with the current season. He negotiates prices while admirers speak overtly about the tragedy of such a talented artist dying so young.

âWhat better way to remember Elizabeth than to display and sell her masterpieces at the wake,â heâd said with enthusiasm. âEclectic art is all the rage now.â

I nodded my consent, but I knew better. Lincoln Cooper couldnât care less about paying tribute to Mom. He hardly knew her. All he cares about is his big fat commission. And considering heâs priced each painting well beyond what Mom would approve of, I donât think heâll have trouble getting what he wants. Sheesh. Maybe this is a cocktail party. Let him have his fun. I only want one painting for myself, along with Momâs sketchbooks.

The essence of her surrounds me. In every brushstroke and ebony pencil rub. In the scent of canvas. In the crinkle of brown paper as Lincoln unwraps a new piece to replace one heâs just sold. My lower lip quivers, and I suck it in between my teeth. Mom would want me to be brave now, but how can I be? Sheâll never again sit on our roof and paint he sun rising over Central Park. Never send me down the block to pick up a new box of pencils from Staples or sketch me while I do my homework.

At once I canât breathe. Iâm suffocating, but no one notices. I canât be here anymore. I wonât do this. Sheâs not dead. She canât be.

AUTHOR BIO—SARA ELLA

Not so long ago, SARA ELLA dreamed she would marry a prince (just call her Mrs. Charming) and live in a castle (aka The Plaza Hotel). Though her fairy tale didn’t quite turn out as planned, she did work for Disney–that was an enchanted moment of its own. Now she spends her days throwing living room dance parties for her two princesses and conquering realms of her own imaginings. She believes “Happily Ever After is Never Far Away” for those who put their faith in the King of kings.

Not so long ago, SARA ELLA dreamed she would marry a prince (just call her Mrs. Charming) and live in a castle (aka The Plaza Hotel). Though her fairy tale didn’t quite turn out as planned, she did work for Disney–that was an enchanted moment of its own. Now she spends her days throwing living room dance parties for her two princesses and conquering realms of her own imaginings. She believes “Happily Ever After is Never Far Away” for those who put their faith in the King of kings.

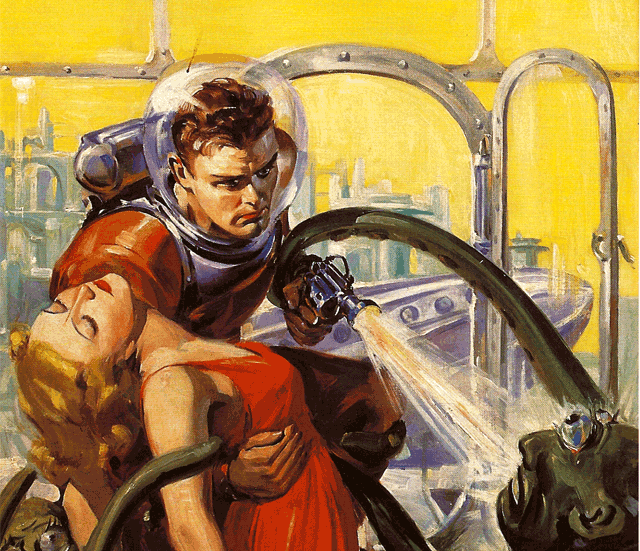

The reigning stereotype of early sci-fi was the young lady, invariably attractive, who was the love interest of the young hero, or the daughter of the old professor, or â this was not rare â both. Often, this young woman played Watson to the menâs Sherlock, asking what the audience doesnât know. Thus the woman provided a method to resolve the eternal writerâs problem of the info-dump, and an infinitely more graceful one than having the hero and the professor tell each other what both already know. More significantly, the young woman is usually the storyâs heart â the heroâs inspiration and the center of his emotion. Often enough, she is the damsel in distress, awaiting rescue. In short, early sci-fi stereotypes fit women into classic ideals of femininity, though it must be noted that this did not wholly sideline women from the action. It was not unusual for the heroâs love interest to accompany him into peril, nor unknown for her to use a weapon when the crisis demanded it.

The reigning stereotype of early sci-fi was the young lady, invariably attractive, who was the love interest of the young hero, or the daughter of the old professor, or â this was not rare â both. Often, this young woman played Watson to the menâs Sherlock, asking what the audience doesnât know. Thus the woman provided a method to resolve the eternal writerâs problem of the info-dump, and an infinitely more graceful one than having the hero and the professor tell each other what both already know. More significantly, the young woman is usually the storyâs heart â the heroâs inspiration and the center of his emotion. Often enough, she is the damsel in distress, awaiting rescue. In short, early sci-fi stereotypes fit women into classic ideals of femininity, though it must be noted that this did not wholly sideline women from the action. It was not unusual for the heroâs love interest to accompany him into peril, nor unknown for her to use a weapon when the crisis demanded it.

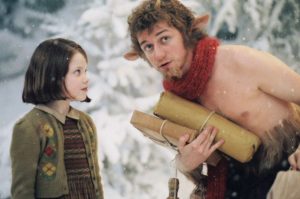

Actually this statement misrepresents Lewis’s position. Certainly, he stated clearly he was not intending to write an allegory when he penned The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. And Lewis thoroughly understood allegory. After all, his first work of fiction was Pilgrim’s Regress, an imitation in style of John Bunyan’s definitive allegory, Pilgrim’s Progress.

Actually this statement misrepresents Lewis’s position. Certainly, he stated clearly he was not intending to write an allegory when he penned The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. And Lewis thoroughly understood allegory. After all, his first work of fiction was Pilgrim’s Regress, an imitation in style of John Bunyan’s definitive allegory, Pilgrim’s Progress.

An author of tales should immediately recognize that a lot of war story writing has been focused on these unusual people. The villains, those who kill and feel nothing for any one–the heroes, who do feel, but are so calm and level-headed they manage to do the right thing even in the worst of scenarios. These are the men of legend and history, these are the Odysseus, the Achilles, the Spartacus, and Audie Murphy figures; the other half represents Genghis Khan, Ashurbanipal, and Joachim Peiper.

An author of tales should immediately recognize that a lot of war story writing has been focused on these unusual people. The villains, those who kill and feel nothing for any one–the heroes, who do feel, but are so calm and level-headed they manage to do the right thing even in the worst of scenarios. These are the men of legend and history, these are the Odysseus, the Achilles, the Spartacus, and Audie Murphy figures; the other half represents Genghis Khan, Ashurbanipal, and Joachim Peiper. Here weâre getting closer to the fantasy and sci-fi writers realm of the fantastical. The race of Sâkrells have an objective to conquer the new human homeworld of Nova Prime. Their weapon? Creatures known as Ursas who can sense fear in the human population. How do humans respond? The Ranger Corps, an elite unit of soldiers selected and conditioned to suppress their fear in order to combat the Ursas (a skill known as ghosting). Itâs with that context we watch a pretty vanilla story about a father-son relationship.

Here weâre getting closer to the fantasy and sci-fi writers realm of the fantastical. The race of Sâkrells have an objective to conquer the new human homeworld of Nova Prime. Their weapon? Creatures known as Ursas who can sense fear in the human population. How do humans respond? The Ranger Corps, an elite unit of soldiers selected and conditioned to suppress their fear in order to combat the Ursas (a skill known as ghosting). Itâs with that context we watch a pretty vanilla story about a father-son relationship. We witness the results of this genetic modification, combined with regimented conditioning, through the franchise, and only in recent years are we seeing the storyline of the movies open up to the possibility of a Stormtrooper breaking out of that mold in the character Finn. Stormtroopers appear fearless against any foe, against any race or species of the galaxy, even against the droid army on Geonosis. Just pull the blaster trigger. Donât think, donât react. Donât respond to fear.

We witness the results of this genetic modification, combined with regimented conditioning, through the franchise, and only in recent years are we seeing the storyline of the movies open up to the possibility of a Stormtrooper breaking out of that mold in the character Finn. Stormtroopers appear fearless against any foe, against any race or species of the galaxy, even against the droid army on Geonosis. Just pull the blaster trigger. Donât think, donât react. Donât respond to fear.

It’s fun to think about, and it’s certainly within the realm of God’s power to preside over infinite worlds, but in the end, it doesn’t matter. This reality is the only one I will ever know, and in this reality, I am a sinner saved by grace. Questioning the very fabric of reality unravels the sweater into nothingness, and questioning something doesn’t change its state of being. Someone says, “What if we’re all just plugged into the Matrix? What if we’re just one possible variation of infinite possibilities?” etc. etc. Well, what if this actually is reality and it’s the only one? And since that’s the more likely conclusion, let’s just go with that. Even if I did somehow find out that there were other versions of me in other versions of the universe, it wouldn’t affect my life here nor God’s sovereignty over all creation, because all of those other universes would still be created by Him.

It’s fun to think about, and it’s certainly within the realm of God’s power to preside over infinite worlds, but in the end, it doesn’t matter. This reality is the only one I will ever know, and in this reality, I am a sinner saved by grace. Questioning the very fabric of reality unravels the sweater into nothingness, and questioning something doesn’t change its state of being. Someone says, “What if we’re all just plugged into the Matrix? What if we’re just one possible variation of infinite possibilities?” etc. etc. Well, what if this actually is reality and it’s the only one? And since that’s the more likely conclusion, let’s just go with that. Even if I did somehow find out that there were other versions of me in other versions of the universe, it wouldn’t affect my life here nor God’s sovereignty over all creation, because all of those other universes would still be created by Him.

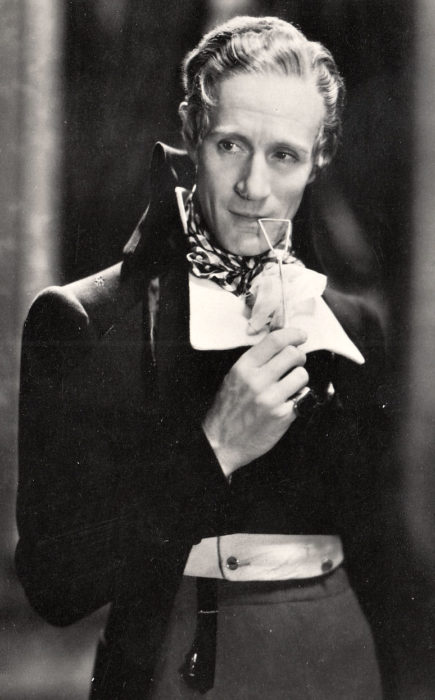

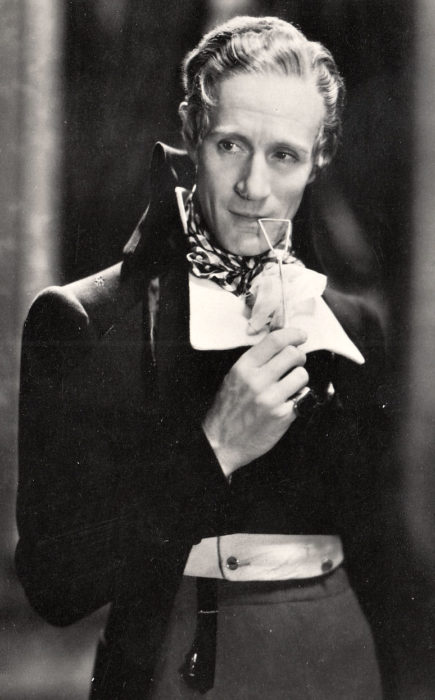

I donât have a favorite hero, because I canât commit to a favorite anything. But I think Sir Percy Blakeney is often overlooked.

I donât have a favorite hero, because I canât commit to a favorite anything. But I think Sir Percy Blakeney is often overlooked. When The Legend of Tarzan released in 2016, I drooled in the theater and babbled all the way home like the nerd I was.

When The Legend of Tarzan released in 2016, I drooled in the theater and babbled all the way home like the nerd I was. As an author, I love telling stories about heroes we could hope to emulateânot because they are unrealistically flawless, but because they face dark times by clinging to integrity and stepping out in courage.

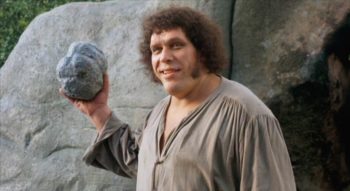

As an author, I love telling stories about heroes we could hope to emulateânot because they are unrealistically flawless, but because they face dark times by clinging to integrity and stepping out in courage. One of my favorite heroes is a bit unconventional. It’s Fezzik the giant from The Princess Bride. He’s not someone who is normally thought of as a hero, but I think he is because of a few specific reasons.

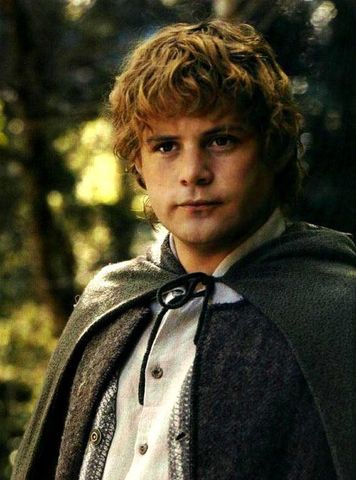

One of my favorite heroes is a bit unconventional. It’s Fezzik the giant from The Princess Bride. He’s not someone who is normally thought of as a hero, but I think he is because of a few specific reasons. Our entertainment is filled with a particular type of reluctant heroâthose âchosen onesâ who understand their high callings in life but just want to be normal, for heaven’s sake. And while I love those Harry Potters and Frodos in my fantastical stories, my hands-down favorite male character breaks that mold.

Our entertainment is filled with a particular type of reluctant heroâthose âchosen onesâ who understand their high callings in life but just want to be normal, for heaven’s sake. And while I love those Harry Potters and Frodos in my fantastical stories, my hands-down favorite male character breaks that mold.

I think writers of Amish fiction might have a place in their stories for “weak” women. They may have strength of character or spiritual depth that far outstrips the men in their lives. I’m not well schooled in the genre, so I don’t know for sure, but after reading IB’s article, I got to wondering whether or not women can relate to the women in Amish fiction more than they can relate to “two-dimensional, plastic characters who walks about like trained prize-fighter in stilettos?”

I think writers of Amish fiction might have a place in their stories for “weak” women. They may have strength of character or spiritual depth that far outstrips the men in their lives. I’m not well schooled in the genre, so I don’t know for sure, but after reading IB’s article, I got to wondering whether or not women can relate to the women in Amish fiction more than they can relate to “two-dimensional, plastic characters who walks about like trained prize-fighter in stilettos?” I suppose the real challenge for writers is to fairly represent characters of various stripes. All our female lead characters don’t have to be girls that can hold their own with the guys on the team. Nor do they all have to be vulnerable victims that need a man’s protection. Maybe we can get away from the stereotypes of both extremes and write women characters who are, you know, like real women are.

I suppose the real challenge for writers is to fairly represent characters of various stripes. All our female lead characters don’t have to be girls that can hold their own with the guys on the team. Nor do they all have to be vulnerable victims that need a man’s protection. Maybe we can get away from the stereotypes of both extremes and write women characters who are, you know, like real women are.

I am old now. I still live on the same farm where I grew up, the same farm where my mother’s accident took place, the same farm that burned for days after the angels fell. My father rebuilt the farm after the fire, and it was foreign to me then, a new house trying to fill an old space. The trees he planted were all fragile and small, and the inside of the barns spelled like new wood and fresh paint. I think he was glad to start over, considering everything that summer had taken from us.

I am old now. I still live on the same farm where I grew up, the same farm where my mother’s accident took place, the same farm that burned for days after the angels fell. My father rebuilt the farm after the fire, and it was foreign to me then, a new house trying to fill an old space. The trees he planted were all fragile and small, and the inside of the barns spelled like new wood and fresh paint. I think he was glad to start over, considering everything that summer had taken from us. AUTHOR BIO—SHAWN SMUCKER

AUTHOR BIO—SHAWN SMUCKER