The last article in this series looked at exceptional human beings and their reactions to combat over the long-term in terms of their ability to manage the stresses of warfare without suffering psychological harm. This article looks at the physical effects a life or death struggle has on a person during fighting itself and next weekâs article will go into long-term effects of combat on human beings. (Information below is derived from Lt. Col. Dave Grossman’s book, On Combat. Psychological effects in general, including perceptual distortions, are summarized in an article on Lt. Col. Grossman’s website.)

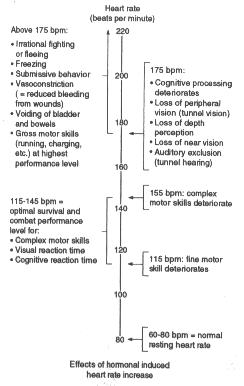

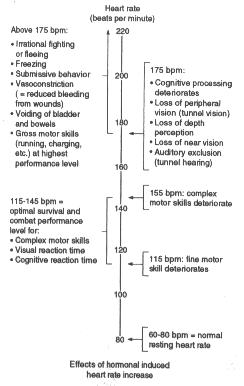

Letâs observe up front that there are inherent difficulties in this kind of study. People going into battle donât usually have heart monitors attached to them. But the available evidence from laboratory experiments shows that when the human heart rate increases from stress alone (as opposed to exercise), certain predictable effects take place:

Note a trend in this chart. A certain level of elevation of the heart rate, between 115-145 bpm, benefits everything a human being can do, except fine motor skills. (If you need to thread a needle, it’s best to be at resting heart rate.) Beyond that heart rate, human performance generally deteriorates, except for gross motor skills and movement, which are best over 160. The heart rate that supports best the activities of, say, swinging a sword with a full adrenaline power boost, generally shuts down the higher brain functions that are good at conducting strategy.

One of the effects of training is to be able to enable a warrior to act appropriately in combat by rote memory, a.k.a, âmuscle memory,â which is especially necessary in physical combat, since higher brain functions tend to shut down.

Another form of training, probably more ancient that the Zen Buddhism that utilizes this approach, teaches a warrior to calm himself or herself, in particular through controlled breathing. Note that an archer needs calmness more than a front-line swordsman. And a bomb-disposal technician needs to be even calmer than an archer.

In stories, human characters who are good at fine motor skills under stress (like bomb disposal) should not be sweating with a pulse throbbing in the neck–the person good at that kind of job will strike others as being unnaturally level-headed, eerily calm, like someone with “ice water in the veins.” Being a berserker works for a swordsman. A berserker bomb disposal technician, or berserker archer–or fighter pilot–is not a realistic character.

The higher heart rate chart only tracks some of the effects combat stress can have on a human being. The following chart is from On Combat, based on a study done on police officers in kill-or-be-killed encounters:

One of the difficulties concerning this chart is it’s hard to fully match it up with the heart rate chart above. It’s not as if police officers in a shootout–or soldiers in combat–are wearing a heart monitor during action. But other studies seem to indicate most of these perceptual changes occur most often when the heart beats over 160 per minute.

Another difficulty with the chart is that not everyone experiences the same effects. I personally (Travis P) have experienced high-stress situations that include both combat and non-combat situations (non-combat including involvement in traumatic accidents). People who read my descriptions of combat will find characters having strange random thoughts in the midst of stress, or making odd, out-of-place observations. According to the chart above, only 26% of people under circumstances like ones I have experienced reported “Intrusive Distracting Thoughtsâ (though perhaps fewer people reported them than actually happened). An example of an âIntrusive Distracting Thoughtâ would be if a rocket exploded less than fifty meters from where youâre standing (for me, on the other side of a concrete wall) and you feel a shock wave impact your body and know according to training you need to run to a nearby bunker, yet the thought passes through your mind, âWhat a pretty blue the sky is today.â Thatâs the last sort of thing youâd expect someone to think in the midst of a life or death situation–but such thoughts actually do occur to some people in the real world during times of extreme stress. Including me.

I personally have also experienced diminished sound, tunnel vision, automatic pilot (where you can act but cannot speak), slow motion time, and a degree of dissociation. I write what I know myself, but studying information like that in the chart above has helped me understand my own reactions are not necessarily the only ones–and are not necessarily typical.

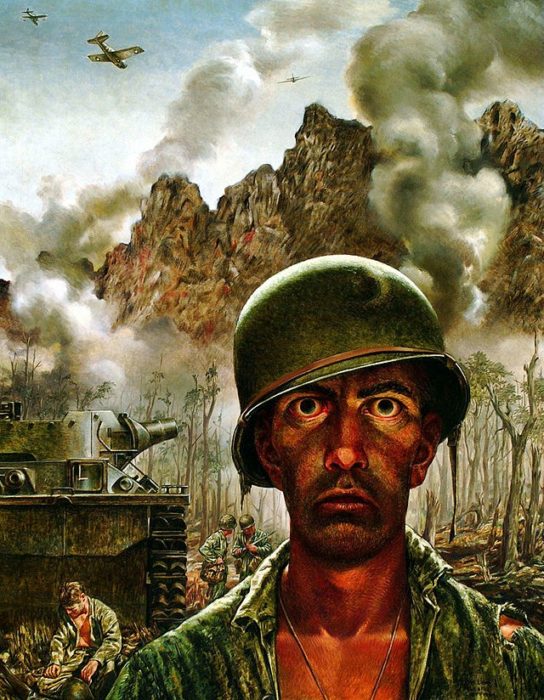

(A crude example of stress tunnel vision–my peripheral vision I remember as more reddish…) Credit: Monderno.com.

Some of these perceptual reactions can be very adaptive. For example, slow motion time, caused by the brain increasing its processing rate, gives the ability to react to something happening much more quickly than a person normally could do. Yet often a person experiencing slow motion time is not able to make a good independent decision and will only usually be able to repeat something learned by rote in training. Lieutenant Colonel Grossman points out that a person can repeatedly train in high stress situations and learn to think and act more rationally, while still reaping the benefits of greater gross motor ability and perceptual benefits such as slow motion time. This is part of the secret of success of special forces units, according to Grossman. They train in high stress so often, they are very nearly fully functional mentally with heart rates over 160–as opposed to not having any increased heart rate at all. (Though very little change in heart rate is probably what happens for certain highly unusual individuals in combat. Though it is simply unknown if naturally elite soldiers have a different set of effects than most people.)

Let me part by pointing out that these are natural human reactions and seem to transcend culture, as best anyone is able to determine. But they are natural reactions, so a speculative fiction story could easily feature artificial manipulation of these effects. Say, designer drugs or a magical spell that let one effect, say slow-motion time, be turned on without the negative side effect of, say, being unable to speak. (Of course these drugs or spells could go horribly wrong somehow.) Clearly a cyborg does not operate by these rules at all and could be completely calm in battle. Which is in fact portrayed often enough in science fiction.

Second, these are natural human reactions. Lord of the Rings Dwarves might go straight to a high heart rate, getting gross motor benefits, while nonetheless being able to think. Elves may stay icy calm, but still be able to fight. Aliens from other worlds might have high stress reactions quite unlike humans altogether. For example, an alien race might have to fight a natural tendency to go into deep hibernation based on a common predator of theirs that would not detect them in that state (which would be far from adaptive when fighting humans).

Overall, combat stress reactions are a reality any fiction writer who portrays combat should be considering. People donât think the same way during combat as they do during situations without stress, though those effects might be different than what youâd anticipate. This topic can provide some especially interesting story opportunities for speculative fiction writers.

Travis C here with a few illustrations of physical combat reactions. I recall a time when I ended up sinking my sailboat with family aboard. Once we were all ashore several people mentioned how calm I sounded over the marine radio: âWe didnât think anything was going wrong until you called MayDay.â Well, thatâs training for you. During months at sea as a submariner we trained in simulated high-stress environments for the kinds of casualties we anticipated might occur, and when they did occur (I have many memories of fires underway and submerged), our teams tended to react appropriately with a combination of rote action while maintaining decision-making capacity.

Working through the physical reactions of characters in combat in the right level of detail can be a challenge. In a world of audio-visual stimuli, the media moguls have given us many beautiful examples of these combat reactions that convey the reality of the warrior coping with his or her natural reactions coupled with training and experience. The film director can cut to scenes of pulsing blood vessels, dilated pupils, cut the sound out or narrow the field of vision, make us experience the pounding chest and heavy breathing. We can experience those reactions through observation. As writers, our job is tougher.

We need to keep the scene moving forward toward its payoff, driving the plot and character development while keeping with a theme and narrative arc. We need to be descriptive in a way that engages and captures the reader. A battle might last hours, or days or weeks of persistent action with random lulls. How many times can we write âHer pulse pounded and vision narrowedâŠâ before losing their attention? Your ability to use tools like metaphors and navigate the dreaded adverb will be challenged in order to show, not tell, whatâs happening.

Letâs look at some popular examples of these combat reactions with some possible writing exercises to go along.

Slowing down the problem

Two movies that show (not tell) the experience of time slowing down are The Matrix and Wanted. The Matrix is likely the more familiar and introduced the world to a unique form of filmmaking and special effects as the digital avatars of the characters wove their way in acrobatic delight while firing near-infinite magazines. Once Neo came to accept his identity and figured out how to do so, he could move as fast as the Agents due to understanding the rules of the program and how to manipulate it.

Credit: YouTube: The Matrix Reloaded (Note that unlike The Matrix, real world slowed time is at a natural maximum about 1/3 speed–which isn’t fast enough to dodge bullets.)

In Wanted, James McAvoy plays an unassuming office worker who is really the son of a supernaturally-gifted assassin. His test to join the guild? Shooting the wings off flies while threatening to be shot himself. We witness his internal reaction as heightened abilities take over and he watches in slow-motion each flyâs wings beat.

Writing prompt: How can you describe a characterâs reaction to internally speeding up their actions and the perception of time slowing? What language might capture a before/after moment? One possible example is a character âseeing the problem throughâ and having time to visualize future actions until success (i.e., Robert Downey Jr. in Sherlock Holmes).

Sight and sound

Hitting the beach. Credit: D-Day Overlord.com

The use of camera lens techniques and audio muting is easy to play with in visual arts like movies, but requires a writer to describe their charactersâ senses working. Travis P described examples of auditory reactions in combat; reducing outside noises to a din, or the opposite as multiple sounds overwhelm a personâs natural processing capacity. Visually we know of narrowing of vision, a possible reaction by the body to shut-out unwanted stimuli and focus a person toward the highest threat. We witnessed these techniques in Saving Private Ryan during the opening scenes as Captain Miller exits his landing craft and hits the beach. Shells going off all around, we watch the dazed vision and hear the persistent ringing as he fights for control of his body.

In movies like Dracula Untold we have examples of magic (or supernatural causes) enhancing those traits to improve a warriorâs effectiveness. Luke Evans plays Count Vlad who makes a deal with a near-immortal vampire to gain strength to defend his people. When he awakes from the transfer of power he is acutely aware of his new abilities, including hearing a spider weaving its web (an example of a distracted thought in the next section). He is able to use these abilities to his advantage, but we also witness the potential side effects of a warrior having enhanced senses (both in creating blindspots as well as his overall cost of gaining such abilities).

Writing prompt: Pick one sense, sight or sound, that your character will experience a combat-related impact to. Imagine what that change will be like on the battlefield. Cover your eyes to slits or ears and describe the difference in words. What does the lack of periphery look like? What fills the void when sound is cut out? What will penetrate that barrier?

Distracted Thoughts

Credit: wot.wikia.com Rand al’Thor

Travis P mentioned the brilliant blue sky. Iâm imagining a light, folky soundtrack playing in the background as mist-formed sheep graze across pastures of blue sky and the sudden return to reality when the moment passes. We often see this reaction, either the unintentional distracted thought or the ability to remain engaged while having distracted thoughts, in an almost comic trope. The expert swordsman fighting off an adversary while looking away and having an unrelated conversation. The completely random line or thought thrown into a fight scene to add levity while showing the distracted response (OK, Iâm guilty of thisâŠ)

Robert Jordanâs Wheel of Time series includes an interesting take on this in the form of a mental candle flame. During his initiation into the warrior role, main character Rand is taught to imagine a flame in his mind that he focuses his attention and energy into as a method establishing control of his physical and emotional reactions in high-stress environments like combat. As this practice becomes more mature he is able to engage opponents while having simultaneous and seemingly unrelated thought trains that the reader follows. Strategy, tactics, relationships: itâs all fair game. In that way the fighting scenes are broken up and we donât have as much run-on fight sequence but we do get more character insight.

Writing prompt: What detail can you provide about your character in the form of a distracted thought? How will you deliver that detail (humor, off-handedness, weightiness, grim, sarcasm)?

These little details add up. They paint a realistic picture of your characters reacting to the stimuli of combat and their natural responses. When you choose to deviate from a humanâs natural reactions, give your reader a reason to believe you. Is it due to a difference in species or race Travis P spoke of? Genetic or supernatural causes? Weâll suspend disbelief up to a point, but you should provide a plausible explanation at some point. Even if itâs the impact of unicorn horn and fairy dust.

quickly juxtaposed by the bureaucratic procedures that surround entering and leaving it. The dead themselves hustle about on humdrum activities â working, traveling, eating and drinking, going to talent shows and arguing with customer service. They do much what they did in life, only they do it without skin. On some level, this is a pleasing incongruity; on another, it is a letdown. Why go to all the trouble to die if life just goes on the same?

quickly juxtaposed by the bureaucratic procedures that surround entering and leaving it. The dead themselves hustle about on humdrum activities â working, traveling, eating and drinking, going to talent shows and arguing with customer service. They do much what they did in life, only they do it without skin. On some level, this is a pleasing incongruity; on another, it is a letdown. Why go to all the trouble to die if life just goes on the same?

The king’s gardener spoke the secret language of all growing things. She knew the songs of the morning flowers and spoke the poems of the weeks. She spent long afternoons in conversation with the trees. From “the Triumph of the Peasant King,” A Scrim Legend

The king’s gardener spoke the secret language of all growing things. She knew the songs of the morning flowers and spoke the poems of the weeks. She spent long afternoons in conversation with the trees. From “the Triumph of the Peasant King,” A Scrim Legend A hummingbird spun into the air beside her, its shining green body hanging to the right of her face. It chirped three times, then zipped to her left, its small, dark eyes studying her before disappearing toward the pineapple sage. The citrusy fragrance of the roses hung heavy across this part of the path. She took little half breaths, and it felt close to natural. The bees hummed as they visited the flowers. A squirrel hung off a sunflower by its hind lets, plucking seeds out of the wide circle of the flower’s face with its forepaws. This garden never quite seemed to follow the seasons . . . sunflowers blooming in spring instead of summer, roses year-round, frogs singing in the evenings no matter the weather. It was an oasis of near-magic in their suburban lot. Madeline used to build fairy houses along the “shore” of the fountain when she was a kind, using bark, leaves, and flowers to make tiny homes for make-believe friends.

A hummingbird spun into the air beside her, its shining green body hanging to the right of her face. It chirped three times, then zipped to her left, its small, dark eyes studying her before disappearing toward the pineapple sage. The citrusy fragrance of the roses hung heavy across this part of the path. She took little half breaths, and it felt close to natural. The bees hummed as they visited the flowers. A squirrel hung off a sunflower by its hind lets, plucking seeds out of the wide circle of the flower’s face with its forepaws. This garden never quite seemed to follow the seasons . . . sunflowers blooming in spring instead of summer, roses year-round, frogs singing in the evenings no matter the weather. It was an oasis of near-magic in their suburban lot. Madeline used to build fairy houses along the “shore” of the fountain when she was a kind, using bark, leaves, and flowers to make tiny homes for make-believe friends. Whether it’s writing fantasy and science fiction novels, or writing spiritual books (yes, Christian spiritual books), I am passionate about creating books which are entertaining and change the lives of my readers for the better.

Whether it’s writing fantasy and science fiction novels, or writing spiritual books (yes, Christian spiritual books), I am passionate about creating books which are entertaining and change the lives of my readers for the better.

In many respects, we’re witnessing in the US the change in the Thanksgiving Day celebration from a major holiday to a minor one. The presence of Thanksgiving or harvest day celebrations seem more apt to be important to a culture if the people are in tune with the growth cycle. As our urban society has become divorced from the way food gets to our table, we seem less thankful and more inclined to take for granted the food we eat.

In many respects, we’re witnessing in the US the change in the Thanksgiving Day celebration from a major holiday to a minor one. The presence of Thanksgiving or harvest day celebrations seem more apt to be important to a culture if the people are in tune with the growth cycle. As our urban society has become divorced from the way food gets to our table, we seem less thankful and more inclined to take for granted the food we eat.

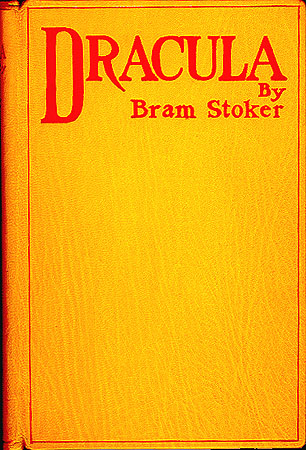

When I joined Jonathan Harker, rolling into Transylvania for the first time, I had this bizarre sense: that Dracula might be like one of those old genre books that you suspect doesnât have a lot of genre in it. Itâs a silly suspicion, but I had it. What if the book barely had any vampires? What if it were just some dry pseudo-historical tale, and in fact the modern vampireâcape, fangs, and allâis a modern mutation?

When I joined Jonathan Harker, rolling into Transylvania for the first time, I had this bizarre sense: that Dracula might be like one of those old genre books that you suspect doesnât have a lot of genre in it. Itâs a silly suspicion, but I had it. What if the book barely had any vampires? What if it were just some dry pseudo-historical tale, and in fact the modern vampireâcape, fangs, and allâis a modern mutation? Iâm no late-19th-century Gothic literature scholar, so I donât know how much Stokerâs style and themes followed or diverged from expectations of the era. But I do know that even 120-plus years later, Dracula and especially his three vampire henchwomen were described as overtly sensual and sexualized.

Iâm no late-19th-century Gothic literature scholar, so I donât know how much Stokerâs style and themes followed or diverged from expectations of the era. But I do know that even 120-plus years later, Dracula and especially his three vampire henchwomen were described as overtly sensual and sexualized.

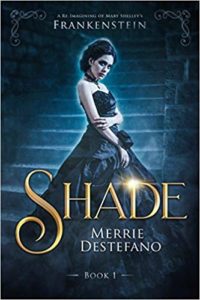

Frankenstein meets Dracula in this Gothic retelling of Mary Shelley’s classic tale.

Frankenstein meets Dracula in this Gothic retelling of Mary Shelley’s classic tale.