Speculative Fiction Writer’s Guide to War, part 10: The Aftermath of Combat

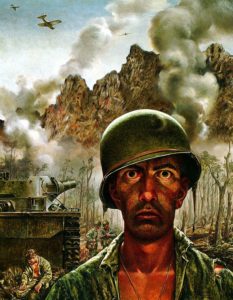

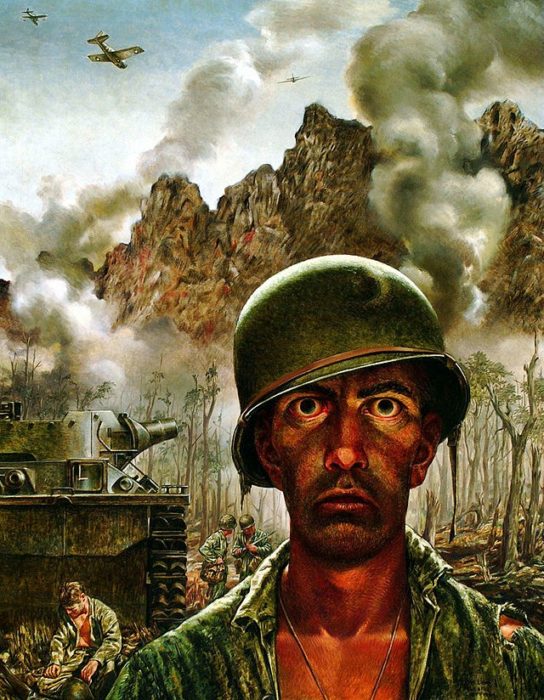

Travis P here. The picture I’ve included above is by Tom Lea, an artist who traveled with US Marines in the Pacific during World War II (this particular painting is called “The Two Thousand Yard Stare”). The image captures better than words ever can one of the effects combat has, a particular example of what the aftermath of combat can be.

I first meant this post to talk about long-term after the fact effects of combat, how it changes the warrior who fights in battle permanently. But I’ve found the actual information on this topic more elusive than I believed it was. So I’m going to broaden the topic a bit to talk about the effects of combat after the fact in general, not just long-term.

Let’s start with the “thousand yard stare.” I read one source that suggested that eyes staring unfocused in the distance is adaptive for survival, because by not focusing on any particular thing, the peripheral vision expands, so any potentially dangerous motion is easily detected. I mention this source more to illustrate that many of the actual realities of why human beings do what they do under various circumstances is in fact still at least partially a matter of speculation. And sometimes a whole lot more than “partially” speculative.

Unlike the source I just quoted, I think it’s more normal to see the thousand yard stare as a product of information overload to the brain. Normal eye movement, normal inquisitive engagement of the environment ceases, because the brain has seen enough and engaged enough. It may be true a person in that state defaults to a form of vision designed to pick up motion, but the primary reason for such a reaction is sensory and emotional overload.

Such a state of staring is usually temporary, as are all the effects of what is now commonly called a “Combat Stress Reaction.” In addition to the stare, troops coming off hard fighting often share the following traits:

Slowing of reaction time

Slowness of thought

Difficulty prioritizing tasks

Difficulty initiating routine tasks

Preoccupation with minor issues and familiar tasks

Indecision and lack of concentration

Loss of initiative with fatigue

Exhaustion

Headaches

Back pains

Inability to relax

Shaking and tremors

Sweating

Nausea and vomiting

Loss of appetite

Abdominal distress

Frequency of urination

Urinary incontinence

Heart palpitations

Hyperventilation

Dizziness

Insomnia

Nightmares

Restless sleep

Excessive sleep

Excessive startle

Hyper-vigilance

Heightened sense of threat

Anxiety

Irritability

Depression

Substance abuse

Loss of adaptability

Attempted suicides

Disruptive behavior

Mistrust of others

Confusion

Extreme feeling of losing control

Obviously not everyone experiences all of these traits. In fact, a number of these reactions cannot be experienced together because they are opposites, e.g. excessive sleep versus insomnia. For most people exposed to combat, a have a number of these reactions (but not all of them) are normal. And for most warriors, the bulk of these effects fade after a few days. The experience of US Military medicine in WWII indicated that a person was in fact more likely to fully recover from “battle fatigue” if after only a short break he returned to his unit and continued to engage in combat. Why this is true is a matter of speculation, but it may be the case that someone who disengages from combat stress can see himself as a permanent failure if not allowed to return to duty with the rest of the “normal” soldiers.

Acute or short-term combat reactions are fairly well understood. Most people experience them at a level that will hamper their ability to continue fighting if under enough combat stress–that amounts to something like 96% to 98% of all combat soldiers if under continuous contact with the enemy for an extended period (6 weeks or more). This figure comes with a very small group of exceptions, as previously noted in the previous post, The Fearless Elite, who show no observable reaction to combat, even of the sort that causes most warriors to become psychological casualties. Yet a reaction to combat stress can exist at a level which affects a warrior without fully paralyzing him or her and is in fact common.

The list of affects above starts to morph into longer-term effects when it lists depression, substance abuse, loss of adaptability, attempted suicides, disruptive behavior, and mistrust of others. These particular traits can become long-term conditions. And acute reactions, from nightmares, to depression, hyper-vigilance, heart palpitations, and more, can occur in someone who has been long removed from combat if something occurs that triggers the memories of warfare. A mild example would be how for a long while after returning from Iraq (where I was subjected to rocket attacks for an extended period), I would “excessively startle” at loud banging noises from firecrackers to slamming doors.

Other reactions include a sense that life outside of combat is ridiculously trivial, which is understandable when dealing with life and death in war versus dealing with running errands in regular life. In addition, a person who has experienced extremes of emotion on the battlefield often shows signs of emotions being fused in ordinary life. So a person can rapidly become angry or experience other rapid shifts of emotion. I found myself experiencing some of the sense that ordinary life doesn’t matter much, as well as quicker-than-normal anger.

My reactions, such as they were, faded in me over a period of several years. They do in fact fade for most people, but for many, never very much. True stories of veterans who suffer from nightmares, or who can not be safely awakened unexpectedly in the middle of the night, or who always sit in the corners of restaurants to keep an eye on an entire room due to hyper-vigilance are extremely common.

Note that modern warfare is different from ancient or medieval in the fact it can put stress on a person day and night for extended periods of time. Usually, in the past, warfare was only fought during daylight hours. Yet even though ancient times record less of people being disabled by psychological stresses, the type of stresses that became greatly evident for the first time during World War I, there still exists evidence that combat stress was a “thing,” even in the distant past. Travis C is going to share how both the Iliad and the Odyssey show elements of how war changes warriors, not just in modern interpretations of those texts, but also in the way these accounts were first composed.

II Samuel 20:12 likewise records how people passing by reacted to an Israelite named Amasa who had been disemboweled and left to die along a road (by Joab). The sight stopped them in their tracks to the degree that Amasa had to be pulled off the road and covered with a cloth for people to keep moving. In other words, even in times where people saw more bloodshed than we do, the sight of a disemboweled man painfully wallowing in his own blood wasn’t something people could ignore. They were clearly affected by it, almost certainly horrified.

And historical accounts of medieval behavior, in which knights seem to show very little emotional control, also function as examples. That is, the knights seem to have demonstrated signs of the kind of emotional swings experienced by someone exposed to traumatic stress. Please note that these stresses are not limited to combat–people can experience this from other kinds of trauma, especially when they are exposed to it as children. Please also note that many children in the medieval world were exposed to violent trauma that would have impacted them strongly–and this would also be common in many worlds of epic fantasy.

This situation is a bit like the fact that nearly everyone in Medieval Europe had at least some scarring from smallpox–yet since everyone had it, they simply considered that condition normal. Having eliminated smallpox from the world, today we see such scarring on people as unusual. Likewise, in modern societies that have eliminated much of the gruesomeness of childhood that was common in the past, we see post-traumatic stress reactions as abnormal. Our ancestors took far less notice of people acting in a way we’d associate with post-traumatic stress–most likely because it used to be far more common.

What exactly is the connection between acute combat reactions and long-term post traumatic stress is difficult to say in a broadly meaningful way. Some people have a greater tendency to suffer from long-term problems than others, though why isn’t clear. Note though that a person is not necessarily disabled by continuing to have (a) post-traumatic reaction(s). People can have sudden unexpected reactions to certain smells or sounds or other stimuli that remind them of their combat stress without being paralyzed by such reactions. People can suffer from black moods and have suicidal thoughts and overcome such conditions, especially with help from others who have gone through the same sorts of things. In fact, it’s important for veterans to realize such reactions are to a degree, normal. And that talking to one another, or at times to professionals, about their experiences is healthy and good.

One factor that seems to relate to how soldiers react to combat over the long-term stems from whether people are able to justify their actions in combat to themselves. A person who looks back and feels he acted morally and correctly does much better in dealing with post-traumatic stress than those who look at back at their own behavior and see it as reprehensible. Note the sense of “morality” I’m referencing does not necessarily mean a person is good–a knight judging his actions from a warped view of Christianity may have felt morally justified in killing defenseless Muslims and Jews (say when Jerusalem was taken in the First Crusade)–that doesn’t mean he actually was justified in a broader moral sense. But the ability to feel justified has always helped warriors deal with the aftermath of combat. Those who cannot justify their actions to themselves have a harder time.

Let me emphasize there is a difference between having post-traumatic stress or a post-traumatic stress reaction and having PTSD–Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The disorder occurs when veterans are disabled by their experiences, when their lives are interrupted significantly. A person can have a certain amount of permanent effects from combat–it is normal in fact to have some–while still functioning in life in a normal way. Or mostly normal…

Stories that include combat should at least consider these realities for both human and non-human characters.

Travis C here with some illustrative resources for writers of combat. As Travis P notes, we’re talking about two broad categories of combat impact: physiological and psychological responses in the midst of action or shortly afterwards (often labeled as combat stress response), and the responses that last after a warrior withdraws from combat and returns to “normal” living. I was at a training session for the Coming Home Dialogues which uses the humanities as a means for veterans to process their war experiences and during a poetry-writing exercise one veteran wrote the following conclusion to a poem about “things every soldier should know”:

You don’t come home.

Sounds harsh, but the message was beautiful. The “you” that began a deployment or mission isn’t the same as the one coming back, and while many effects will pass with time, the experience is etched there and for many the effects do not always pass.

Instead of analyzing the popular media which often captures the physiological responses to some degree (movies can do well as focusing on bodily responses, for instance) and may use story narrative to expose a warrior’s psychological reactions, I’d like to very briefly introduce two resources that helped me work through my own challenges by unpacking two fantasy works of literature: Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Jonathan Shay is a psychologist and counselor of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Two of his popular works are Achilles in Vietnam and Odysseus in America. Each work analyzes the main character of The Iliad and Odyssey respectively and posits that Homer is writing about warrior issues of moral injury and betrayal (Achilles) and the psychological impact of returning home from war (Odysseus). For writers looking to hone their ability to write about warrior culture I can’t recommend each book highly enough.

Credit: www.warnerbros.com/troy

Let’s begin with Achilles. The Greeks have been fighting the Trojans for some time, and Achilles represents the noble, honorable Greek warrior fighting for a just cause. He and his Myrmidon are spectacular in battle, winning many engagements and bringing honor and encouragement to the Greek forces. Then Agamemnon, the king of the Greeks (though not Achilles’ ruler), decides to take back part of Achilles’ rightful war spoils for himself. The movie Troy attempts to capture this moment but fails to fully reveal the cultural and personal affront this is to Achilles. He is enraged at the dishonorable actions of his leadership and is wounded in a moral way: the Greeks no longer serve someone who holds the ethical high ground. In fact, maybe they never did. After losing his brother Patroclus, Achilles goes into a berserk rage as his worldview of rightness and honor comes spiraling down, ultimately leading to his death.

Gavin Hamilton, Achilles Lamenting the Death of Patroclus

www.nationalgalleries.org

The Iliad shows us the warrior’s response to several specific traumas of battle. The death of a close comrade. Wrongful substitution (i.e., survivors guilt). Revenge through a berserk state of mind. The impact of dishonoring the enemy and having the enemy dishonor your own. The destruction of trust in the social and moral order the warrior exists in. A betrayal of what’s right.

The Odyssey represents another interesting case study for writers. If Achilles represents the honorable warrior operating from a worldview of moral rightness, Odysseus represents a different worldview. He is cunning and wily. It is Odysseus who suggests the use of the Trojan horse as a means of breaking through the Trojan forces and winning the war from the inside. Sneak inside, open the gates, kill as many as possible, and the Trojans will break. Prey upon their religious beliefs and lie to them. Odysseus inappropriately takes Achilles’ armor when it should have gone to Ajax. Not exactly honorable conduct.

Once the war is ended the remainder of the Greek forces sail for home after ten long years of sustained combat. Odysseus, King of Ithaca, tries to bring his men home but fails. After ten more long years he washes ashore and becomes a guest of the King of Phaecia. Among the civilian court, trapped in riches and focused on trivial things, Odysseus’ identity is learned and he recounts his tale of wayward misadventures that have cost him his entire army (none of the Ithacans come home except Odysseus).

Shay unpacks the Odyssey in much richer detail than we can do justice to here, but consider the tales of cyclops, sirens, Scylla and other monsters as a metaphor for a returning warrior’s internal challenges to coming home:

- A success warrior’s repertoire of skills looks a lot like a criminal’s. Cunning, critical thinking, adaptability, focus on a task, control of fear, control of violence, capacity to respond skillfully and instantly to danger, disregard for fixed rules if it endangers the mission. Odysseus’ men raid the island of Ismarus and find their warrior training has prepared them for a career as thieves.

- Odysseus’ crew tempt the island of the cyclops for only one apparent reason: to see what would happen. They knew danger lay there, but wanted to see what would happen if they prodded the beast. Returning warriors often find regular life boring and will find ways to create dangerous situations and thrill-seeking even in the midst of peace.

- Odysseus encounters his friend Ajax in the Underworld, and finds within himself “a lack of moral pain, guilt, self-reproach, and self-criticism.” Warriors must wrestle with returning home and often suffer from internal agreements they’ve made, including a relentless search for the truth, an acceptance that anyone close to them will be harmed, and that the losses they suffered are irretrievable. In Shay’s words, “The lone wolf feels at home nowhere.”

Columbia University:

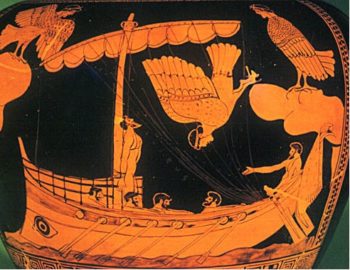

Odysseus and the Sirens, red figure stamnos vase, c. 480-460 BC - It’s often forgotten that the sirens weren’t calling out to the ships’ crews in a sensually seductive manner; they were calling out seductive truths that Odysseus heard nowhere else. They called out selective truths, but truth nonetheless. A warrior will often find themselves on a search for the truth (Why were we really there? What was our true impact? Did ____’s death really matter?) and that struggle may persist for a lifetime.

- To be frank, Odysseus has problems with women. Relationships are challenging to begin with, but combine that with extended time away from one another, limited communications, and the added stress of homecoming expectations and you’ve got a recipe for trouble.

These are but a few examples from each of Homer’s works that describe the challenges a warrior faces when returning home. We recognize the risk of physical injury to the warrior on the field, and can paint a picture of maimed and broken soldiers back in society. The mental tax, the psychological impact of warfare, may not be as well appreciated. We recognize the impacts through secondary effects of the aftermath of combat: the veteran who can’t relate well to others, the warrior who never lets go the memory of a fallen comrade, the pent up anger and frustration if the system has failed them. Good writing will attempt to capture those impacts and show our readers the holistic story of the warrior’s combat experience.

Lastly, as we’ve pointed out before, these are realities for human combatants. Shifting our view to different races or species, the impacts may be different. How a culture processes the aftermath of combat might play a pivotal role in your story. Maybe there are genetic or physiological differences that make a character work different. The contrast to what is recognized as a human condition will be that much more important.

Many thanks to Travis P for his work on this post. It’s a challenging topic that we’re giving limited coverage on, but such a deep one. For those unfamiliar with The Odyssey and the sirens, from Pucci’s translation:

“Come this way, honored Odysseus, great glory of the [Greeks],.. so that you can listen here to our singing; for no one else has ever sailed past this place in his black ship until he has listened to the honey-sweet voice… for we know everything that the Greeks and Trojans did and suffered in wide Troy. Over all the generous earth we know everything that happens.”

We know everything… To someone seeking answers, to someone hurting for the truth, that feels like the most seductive thing imaginable.

Lastly, as we approach Veterans Day here in the US, I humbly challenge our readers to keep your eyes open for an opportunity not to say “Thank you for your service” (though you certainly can), but instead to ask a veteran, “Can you tell me what it was like?”, and to listen. They may not want to share, and that’s OK, but many will appreciate the opportunity to be heard as much as any expressed gratitude. It’s part of our collective story.

Thanks, Travis. I really appreciate all the effort you put into our collaboration. I’m quite happy with our results thus far.

This resonated with me. I’ve told folks before that the guy that left for Iraq died, and someone else came back instead. Folks don’t understand that, but it’s true. But this new guy feels disjointed and left behind.

I don’t think every story needs to have a serious portrayal. Some stories have a tone that won’t work with. But if one is going for a serious tone, do the right research.

I honestly believe a big part of the issue is that certain behaviors, actions, mindsets, so on, are not what God designed us for. In fact, it’s unnatural to do some behaviors, or even to want to do them. So when we push past that natural resistance, we hurt our selves. That’s apart from the acclimating to one environment, and then being unable to acclimate back, feeling left behind, so on.

Your piece spoke to me, and I appreciated seeing what so many go through, myself included, described with such frankness.

Thank you for capturing something we kind of missed: it does feel frank and serious, and it is, but we can certainly approach it differently through our respective genres and writing voices. I enjoyed Last Flag Flying largely because of Bryan Cranston’s character and his humor; much more aligned with who I am and my personality. Many approaches to it, all of which can be done well and accurately reflect internal realities.

Something I noted from reading Grossman’s On Killing was the evidence that suggests belief/trust in the moral authority of one’s combat actions may effect if, and how quickly, someone recovers from the trauma of war. It made me think about Old Testament examples of actions the Israelite army was commanded to undertake. I haven’t completely worked through my thoughts on that, but this series made me head back to consider it. I agree; we are made in God’s image and internal resistances are part of that.

Thanks for your comments.

Yeah, I agree that not every story needs a realistic tone, but what we’re writing here addresses the specific problem of someone who is trying to strike a realistic tone but doesn’t know how. We are providing, as best as we are able, actual truths that will help those seeking realism to find a better understanding of what “real” looks like.

“After losing his brother Patroclus…” LOLOLOL Patroclus wasn’t his brother. (Maybe in the movie, but not in the original.) Patroclus is widely considered to have been Achilles’ gay lover. That was a Thing in ancient Greece, that you had a wife just to get children, your real emotional connection was supposed to have been with your gay lover. Depending on the culture of the particular city-state, women were often seen as only a degree or so above animals.

Also, I don’t think most translations have the sirens singing anything in particular. I’d have to go back to the text for confirmation, but I’m pretty sure TS Eliot would have included that in a poem if they did. Interesting fanon, tho.

I caught myself a bit delayed, so definitely mea culpa on my part. I believe in the movie Patroclus is a cousin, and and in the poetric representation is a close friend likened to the intimacy of battle buddies nearly like kin. I felt Shay’s focus on the death was more to point out how a moral injury (Achilles’ betrayal by Agamemnon) leaves one lacking resilience to further wounding (lose of a brother/sister in arms) that led to his berserk rage episode. Highly simplified, but a logical progression.

I think I have a Fitzgerald translation, but Fagle (my other go-to) translates as follows:

“Never has any sailor passed our shores in his black craft

until he has heard the honeyed voices pouring from our lips,

and once he hears to his heart’s content sails on, a wiser man.

We know all the pains that Achaeans and Trojans once endured

on the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—

all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all!”

Shay unpacks this and the other Odyssey tales through the lens of a warrior suffering from variations of post-traumatic stress and the challenges of coming home. The temptation for Odysseus, troubled by his actions in Troy and the overall conduct of the campaign, to hear exactly what happened during the conflict and to leave a wiser man… sounds tempting. I can think of many examples of someone coming home and wondering “What happened?” Did I accidentally kill a non-combatant? Did my actions cause the death of a teammate? Did any of it actually matter? Those can become lingering doubts in a person’s mind, crippling them or causing them to neglect other responsibilities in the (fruitless?) pursuit of answers.

I can gush for a while on Shay, but highly recommend Odysseus in America.

Oh, I’m not debating on the emotional affect on Achilles, whether Patroclus was a bro-in-arms or a waifu.

Ok, weighing in on this issue. I did some research to verify what I already thought was true but I wanted to be sure. Hence me responding after a few days.

Turns out Notleia’s laughter is quite premature. Patroclus was not related to Achilles, but according to Homer, he got into some trouble in his youth and was sent over to Achilles’ household. So, he was an unofficial adopted brother to Achilles–an older one at that. So the Travis C’s use of “brother” is an OK approximation. (The movie’s use of “cousin” works, too, more or less.)

Patroclus was considered to be a gay lover after the fact, because that’s how Greeks later interpreted the character. Note though that interpretation came hundreds of years after Homer and nearly 500 years (giving a rough figure) after the time of the actual Trojan War that inspired Homer’s epic poem. Was having homosexual lovers as common in the era of Homer and earlier as it became in Classical Greece? In short, no, it was not as common, in fact, such a thing may have been virtually non-existent in Homer’s time, though it’s hard to be sure (the evidence is simply non-existent for the most part). But it’s noteworthy that no direct evidence exists in Homer’s works themselves that Patroclus and Achilles were lovers.

I would say that Patroclus was simply someone Achilles loved. When cultures become sexually obsessed, they have a hard time conceiving of love without a sexual element. But it really is possible to love someone in a non-sexual way. So the kiss of Judas to Jesus and him having a “beloved disciple” to some people sound like Jesus had a series of gay lovers–but of course in Hebrew culture it was entirely possible for men to express non-sexual love for one another, including overt physical affection.

I would say it’s a shame that non-sexual love among men is so difficult to express in the dominant culture of North America without it being construed as physical, sexual love. But we are not the first culture to see everything through the eyes of sex–the Classical Greeks were pretty dirty-minded, too.

I think that’s one reason I like fantasy stories so much. It’s easier to depict close friendships and camaraderie and have the audience understand that those friendships can be purely platonic. Though of course there are still some really aggressive shippers that can’t accept that certain characters’ relationships are platonic regardless of the circumstances.

There are probably shippers who pair odd couples just for the challenge.

Some definitely do, and I think that can be fun sometimes. I think it tends to be fine when people simply like a couple together, even if it’s a strange one, but when people start acting like a couple IS canon(even though the couple very well might not be) or when they act like the couple NEEDS to be canon, that’s when it can get a bit toxic.

I ship plenty of couples that aren’t canon, but at the same time I realize they aren’t canon and think it’s well within the authors’ rights to keep it that way if they choose.

So the wiki told me when I did some reading (of course after the comment posted).

But if you look at it from the postmodern perspective, the fact that it was an accepted interpretation due to later culture means that Patroclus/Achilles is simultaneously both gay and not-gay. Schrodinger’s BL, if you will. (Also Achilles was totally the uke. If he were once disguised as a girl and no one was able to tell until Odysseus tricked him, that means he was totally an effeminate boytoy who could still kill you harder and faster than anyone in Greece.)

Notleia, thanks for introducing me to Achilles on Skyros. I wasn’t familiar with that story. It seems–yes I’m going the easy route and looking at Wiki–that this story is considerably later than the Iliad. Hundreds of years later, in its fullest form by Roman writers.

And the story centers around Achilles using his ability to disguise as a girl to hide his his affair with Deidamia, another of the “daughters” of the king (a daughter, just as he was thought to be). Yeah, the story doesn’t seem to intend Achilles to be a “boy toy” in the slightest, even though that clearly was a thing in the Roman era. At most it says Achilles was envisioned as a young and exceptionally handsome man…which probably was suggestive to women and gay men alike at the time of the creation of the story. But provides no definite statement that Achilles was gay–in fact, quite the opposite.

Your reference to Schodinger strikes me as pretty clever, by the way. Not that you need me to tell you I think you said something clever, but I’ve often been critical when I thought you weren’t clever, so it seems fair for to me to openly state it when I think you were. Yeah, OK, I can see that people have justification to see Achilles and Patroclus in a certain way.

But I imagine you can see why, in the context of discussing warfare, in which very close non-sexual bonding is common and is an experience I’ve certainly had and which Travis C may have had as well, that your comment on Patrolcus was rather entirely beside our point. And still is beside the point here…because warriors can become unhinged by losing close friends or relatives or close comrades in arms (no “other” relationship is required for that)…as per Travis C’s original point.

This kind of reminds me of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and how in modern times we interpret the story vs now. In the legend, Gilgamesh and Enkidu were described as, more or less, good looking, and in many instances there seems to be a big difference between what that means then and now. Like, here’s something along the lines of older interpretations of Gilgamesh:

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/Hero_lion_Dur-Sharrukin_Louvre_AO19862.jpg/220px-Hero_lion_Dur-Sharrukin_Louvre_AO19862.jpg

And here’s a more modern interpretation of him(as seen in Fate Zero):

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-SM8dEnD70IE/TpMfFakAZaI/AAAAAAAABms/yc-liMZS2wU/s1600/Fate_Zero_ED_02A.jpg

And if I recall correctly, in the legend, another guy (Enkidu) was described as being ‘as beautiful as a woman’ or something like that, but a lot of older carvings/depictions still seem to make him look more along the lines of something in that first picture I linked. Sometimes with old legends it’s difficult to know what to take literally(according to our interpretations).

In the Epic of Gilgamesh’s case, it sort of seems like ‘beautiful as a woman’ means that level of good looking, not necessarily that Enkidu looked exactly like a woman. Gilgamesh and Enkidu were also very close, and the legend makes it sound more like a brotherhood than romantic thing. But due to how torn up Gilgamesh was about Enkidu’s death, many people probably are biased to think of their relationship as romantic.

This actually got me thinking about my assassin chars a bit. A major motivating belief in their culture is that people, especially their people, should work to be equally adapted to/comfortable with war and peace, comfort and hardship. They of course want to work to make society better, and don’t rush to war, but they try to teach their citizens to handle it when it comes, and preferably without crippling psychological damage.

So, one thing they do is try to teach a lot of assassination skills in fun ways(some acting and undercover skills are cultivated in small part by having assassin apprentices organize and put on plays) Assassins are also encouraged to have hobbies, and those assigning missions are often informed on the hobbies many of the assassins have and keep that in mind when assigning missions. So, let’s say that an assassin is good with music, and especially the violin. That assassin may be sent undercover as a musician.

So, my question would be whether you think things like that could help keep a combatant from feeling like every day things are too mundane or boring. In this case, we have a culture where every day things are purposefully cultivated not only for fun, but for the sake of honing one’s self for combat, and thus every day things, no matter how inconsequential, matter and are useful. They would also have been taught from day one that every day life is significant in balance with hardship and war, and that the every day things should be significant in and of themselves because they can help keep a person sane enough to return to combat later on.

Also, this video has a few of the things you guys might be talking about, in terms of someone having a different perspective after combat and in response to stress and such. This char might be experiencing more/different stresses, but do you think at least some of the mentioned reactions are realistic given Eren’s experiences? Not necessarily in the sense of everyone becoming that way, but at least plausible for some people?

I find your comment a bit difficult to respond to. First of all, since killing human beings IS really so difficult on the psychology of most humans, portrayals of assassins that treat them more or less like regular people is mostly not realistic. Of course, assassins have regular lives apart from what they do, because people have amazing abilities to compartmentalize different aspects of themselves. But those “regular lives” should be affected or tainted by their profession. Most likely.

An assassin is either from the small set of people who are not seriously affected by trauma or would have at least some effects. An assassin would do better overall if he or she felt justified in killing by some sort of moral code. An assassin who works solely for money should not be the same kind of person as one who fights for some higher purpose.

Part of your comment talks about how your assassins are trained. This comes down to nature/nurture questions. How much of what we human beings do is what we are taught to do and how much is because of things innate in human nature? Are there limits beyond which no human can go?

The questions I just asked are applicable in many ways. Can any human fly by flapping arms? (No) Can any human jump two meter straight up? (Yes, but this is rare and depends of circumstances) Can any human run fast enough across water to stay on the surface, like some lizards do? (No) Can any human swim five minutes underwater, while holding his or her breath? (Yes–but this is exceedingly rare) Can any human being be taught to kill? (No, but most can) Can any human being be taught to kill and suffer no affects after killing people? (Yes, but this is quite rare–most people who face life and death struggles are never the same afterwards) Can training balance out a person’s natural tendency to see life and death struggle as inherently more important than everything else in life? (Yes, but only to a degree–there are limits to what training can change)

I think the kind of thinking you need to engage in to write more genuine characters is concerning what are and are not the actual limits of a human being. I hope that makes sense.

Hm…for context I’ll say that, although they get paid for missions sometimes, that usually isn’t their motivating factor, and many assassins also have other careers they sometimes work at part time between training and missions(since they probably can’t do assassiny stuff 24/7). They do have some strong moral codes, and are basically indoctrinated from birth in the idea that it is often immoral to hesitate when it comes to defending something important(whether that be one’s own life or someone else’s) or when defending the safety/interests of the Guild and its allies. But they also have a list of atrocities that they are supposed avoid committing, murder being one of them. So killing a young, defenseless child is likely to mess them up, but if an adult attacks them with fatal intent then they tend to feel justified. Of course, each assassin will react to each incident in a slightly different way.

I agree that killing is normally going to have some type of affect on the average person, so I wasn’t necessarily trying to ask if their training could keep them from being affected at all(Taira, the assassin I mentioned before that was forced to kill that puppy, is somewhat what her culture sees as an ideal assassin, but a lot of killings do affect her in some way or another still).

But I was curious if being indoctrinated to look at every day life as something that hones them for missions/combat might reduce the feeling of daily life being boring/useless. That probably wouldn’t always be a good thing, even if that was the case, since it might make some assassins feel like they can never truly escape their missions and compartmentalize their life, so…I don’t know. Maybe instead what I should be asking is what you think some potential reactions might be to that kind of indoctrination from birth.

I don’t know if that clarifies anything or has any bearing on the answer, but hopefully it helps.

And I’ll try to keep human limits in mind more going forward. I suppose trying to consider the average person’s actual limits and tendencies is one reason why I ask these kinds of questions. I sort of feel like if I was raised in the assassins’ culture of making practically everything in their lives useful in some way(in terms of honing their skills), that would probably reduce the chances of me seeing every day life as useless and boring(depending on exactly what happened to me), since I would actively be forcing myself to see everything as useful. But I’m trying to figure out if that’s more of an Autumn-is-weird thing or if that’s something a lot of people might experience. I don’t think that kind of mindset is something people really try or think about much, though, so I understand if that’s not really something that can be answered.

I think deliberately training people concerning the value of so-called ordinary things would herd them in the direction of appreciating ordinary things more. I don’t know how much exactly. I haven’t witnessed that kind of training on professional assassins.

My purpose in talking about limits was to get you to think along the lines that while humans can be trained to do many things, there are limits to what training can accomplish. I said all of that with the idea of getting you to consider that your characters will be greatly influenced by their training, yet certain aspects of their experience will seem to run into natural human limits.

The good news is I suspect no one really knows a definitive answer to your question. So you have freedom to make things up–all I’m calling you to do is really think about what human beings are actually like as you make them up. 🙂

Yeah, I’ll just have to work with it I guess. It’ll probably be a few years before I actively start writing on that particular story again, so hopefully I’ll come up with more ways to apply human limits to this by then. 🙂

Great article. Soon after I read it, the Firefly series theme song came up in my playlist and I thought what an excellent example it was for capturing some of the issues discussed in this article. The song doesn’t reference war directly (though the series does) but the sentiments are clearly ones expressed by a returned veteran.

Take my love, take my land

Take me where I cannot stand

I don’t care, I’m still free

You can’t take the sky from me.

Take me out to the black

Tell them I ain’t comin’ back

Burn the land and boil the sea

You can’t take the sky from me.

Leave the men where they lay

They’ll never see another day

Lost my soul, lost my dream

You can’t take the sky from me.

I feel the black reaching out

I hear its song without a doubt

I still hear and I still see

That you can’t take the sky from me.

Lost my love, lost my land

Lost the last place I could stand

There’s no place I can be

Since I’ve found Serenity

And you can’t take the sky from me.

source: https://www.lyricsondemand.com/tvthemes/fireflylyrics.html

Yeah, Firefly’s song is definitely from a Veteran’s point of view, a veteran affected by warfare for life. But also shows that being affected doesn’t necessarily mean being defeated or destroyed. “You can’t take the sky from me.”

Because we need some Uncle Kurt Vonnegut also, too:

“So this book is a sidewalk strewn with junk, trash which I throw over my shoulders as I travel in time back to November eleventh, nineteen hundred and twenty-two.

I will come to a time in my backwards trip when November eleventh, accidentally my birthday, was a sacred day called Armistice Day. When I was a boy […] all the people of all the nations which had fought in the First World War were silent during the eleventh minute of the eleventh hour of Armistice Day, which was the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

It was during that minute in nineteen hundred and eighteen, that millions upon millions of human beings stopped butchering one another. I have talked to old men who were on battlefields during that minute. They have told me in one way or another that the sudden silence was the Voice of God. So we still have among us some men who can remember when God spoke clearly to mankind.

Armistice Day has become Veterans’ Day. Armistice Day was sacred. Veterans’ Day is not.

So I will throw Veterans’ Day over my shoulder. Armistice Day I will keep. I don’t want to throw away any sacred things.

What else is sacred? Oh, Romeo and Juliet, for instance.

And all music is. ”

— Breakfast of Champions (1973)

Armistice Day was sacred because it ended the largest war the world had ever seen. Yet, within just over 20 years, the world had an even BIGGER war. That’s why Armistice Day got eclipsed and transformed into Veteran’s Day (in the United States, that is). Which Vonnegut should have understood as someone who fought in WWII (and maybe he actually did).

We are not done with wars. We are not done with human evil. I wish we were. But we aren’t–there will still be veterans, long after all memories of WWI have faded. Actually, that’s not much of a prophecy, since it’s virtually happened already.

I suppose Vonnegut was longing for an end to war that people cherished on Armistice Day. I don’t fault him for that, but that’s an end that just isn’t coming as long as humans remain human.

Vonnegut as a veteran himself had a right to be a cynical as he wanted to be about remembering the sacrifice of veterans. But I feel justified in tossing that sentiment over my shoulder in the same way he felt justified in doing with Veteran’s Day…I don’t need Vonnegut’s cynicism on this issue. It does me no favors–nor does it really help anyone. In my honest opinion.

Vonnegut had a whole bunch of quotable things to say about (anti-)war. I think him worth reading, especially since he has an enjoyably weird, sci-fi angle to most of his work.

But the people who quote him (who are most likely liberals) in context to the general stupid cruelty of war. Most of these other opinions are about how cruelly pointless Vietnam, Afghanistan, or Iraq was/is. (More than likely, Saudi Arabia was the most responsible for the 9/11 attacks, except they are our friends who give us access to oil and its ~moneeey~~~)

I think this type of anti-war opinion (that does have a lot of veteran adherents) does actually have a point, especially in a society where waaaaaay too many veterans are homeless or medically disadvantaged without effective systems in place to handle them.

Or the part where [Republicans] will natter about the costs of Medicare for All or free community college but don’t spare half a thought for the costs of dropping the Mother of All Bombs [or stationing troops at the border because scary brown people] because they’re too preoccupied with solving all their dysfunctions with big guns and big booms (that do nothing to actually solve the underlying problems.)

The thing I think liberals miss about the cruelty of war–or at least I think they miss it–is that it isn’t stupid. Oh, not that wars don’t contain stupidities–they have vast numbers of idiotic things in them.

But the attitude that “violence never solved anything” that many liberals espouse is simply untrue. Wars in fact “solve” (or better said, resolve) a lot of problems–I mean the solutions are bloodcurdling usually and often turn out unexpectedly, but they are real. To give some examples, German groups that used to be isolated and at times persecuted in Eastern Europe, that Hitler tried to unite, are no longer there. Problem solved/resolved. The desire to fight Communism in Vietnam was poorly organized from many points of view–and it led to the United States pulled out leaving a weak puppet non-Communist government in charge. The Communists invade and re-united Vietnam, deciding what the entire country would become. Problem resolved. The United States and allies did better in South Korea, which today is a modern, prosperous country, while North Korea is a totalitarian hellhole. The fate of South Korea at least was “solved” in a way the USA wanted.

Oh, we can bemoan that human beings can’t work all this out by negotiation. But that isn’t essentially because we are stupid. It’s because we are sinful–as a whole our race is (not me or you specifically), arrogant, hateful, and xenophobic. Liberals who deny the existence of God (not all liberals do that of course) and the reality of sin, offer NOTHING to solve this problem but optimism. Whimsical hope in progress and innate human goodness (HA) and deconstruction of patriarchy and loads of other horse manure that has absolutely no hope of solving anything. True peace starts within each and every human heart–and these hearts are best reached one at a time by the glorious gospel of Christ. Oh, there are plenty of nice people who don’t believe in Christ and plenty of nasty people who say they do. But that’s smokescreen. The power of repentance, in seeing oneself differently (metanoeo in NT Greek) affects even those who do not have faith in Christ. But the Holy Spirit is not a figment of my imagination. The spirit actually is real, really does make changes beyond what mere repentance and thinking of self differently can perform, and really IS found all over the globe, as the world’s best documented set of ancient texts records an otherwise obscure Jewish laborer telling a bunch of otherwise obscure Jews, who had no idea how big the world even was, let alone that their message would be preached all across it. Which is something that Satan, who also is not a figment of my imagination (as much as “clever” people may chuckle about that) tries to get people like you to stop thinking about. Maybe by some lop-eared textual analysis that someone you know with a B.A. in Biblical languages can pick apart without even working up much of a sweat. Yeah, that’s me, but it isn’t because I’m so brilliant, it’s because most of the stuff thrown at the Bible is inherently weak, with only a relative few notable exceptions that don’t really deal with the meat of the Biblical text. These criticisms are floated on a set of academic reputations more than actual logic.

But you buy it–and not just you, many others. Well, it frees you of all responsibility to the Bible text, doesn’t it? How convenient.

This may seem like a rant, but it isn’t. I feel for you, whoever you really are. As I’ve already said to you, you very evidently were raised in a kind of Christian cocoon that you learned to question and now are all snarky about Christianity. Yet the things you have learned since are themselves also weak sauce, intellectually lame-brained, totally incapable of, for example, bringing lasting peace to the human race…though of course your new paradigm sounds much more sophisticated than the one you used to know. I call on you to question your new paradigm with the thoroughness you applied to what you were raised with–you will find (I believe) that what you first had been taught about Christianity was largely true, even if for quite different reasons than the people who taught you as a child thought. (Note that God does not require his own to have brilliant comprehension of all things–God knows the human race and calls us as we ARE–not as we ideally could be. That he works to grow later, bit by bit.)

To back away from what I was just saying for a bit–as dismissive as I am of the notion that wars never solve anything, it is also true that people respond with violence when they stand to gain nothing from it. Yes, that happens too. But your “too preoccupied with solving all their dysfunctions with big guns” is silly. Sure, some people may be like that. But it’s pseudo-psychology to claim that war in general is caused by psychological dysfunction. War is ultimately caused by SIN, even though I believe there’s such a thing as a justified war, and even though there’s also such a thing as an evil war that actually helps those who fight it gain an advantage at the expense of other human beings (an act being rational does not inherently excuse it form being evil). And being evil to some degree or other is a problem all humans have, Republicans and Democrats alike. Including you. So instead of poking at the sins of others, which even the Pharisees at the time of Jesus found easy to do, how are you working out your own issues and creating your own internal peace?

Me, I turn to Christ. You could claim that Jesus does not in fact provide for me to be a more peaceful man than I otherwise would be. But I know from experience you would be wrong about that.

Vonnegut may be clever. I don’t know. I haven’t read him. But what you quoted him saying seemed to indicate he had no idea what is really true about life. Many things are far more sacred, far more important, than Romeo and Juliet. As cool and interesting as that story was.

You can do better than read Vonnegut. Much better.

Something that I’ve seen with war, and a lot of political decisions in general, is that there seems to be a bit of a ‘hindsight is 20/20’ thing going on. Like, around when politicians are making the decision, many people in the public will seem to be for it(from my childhood memories, people reacted like that to September 11), or even criticize politicians for not going to war. But after the war goes on long enough and everyone gets tired of it, people start to deride the war and act like it’s a silly waste as if everyone knew it was a bad idea to begin with. And then it seems that more information comes out with time. More information(and even perspectives) than what politics had to begin with. So it’s easy for us to look back and call decisions stupid, but at the time, those were probably the best decisions many of those politicians felt like they could make.

Also, the border thing notleia mentioned kind of reminds me of something I’ve been turning over a bit in my head lately. Like, there’s tons of people streaming in from Mexico and other countries, and I don’t know how I’d feel if Mexico, etc. tried to force their people to stay, but on a deeper level, I wonder how Mexico’s government and people feel about so many of their citizens leaving, or what they try to do about it. Or if they try to do anything about it at all and why or why not.