On Culture And Giving Offense Or Being Offensive

To be honest, I wanted to write a piggy-back post to the one Travis Perry wrote last Thursday because I think his evaluation of Christians and the way we interact with our culture is both fascinating and thought-provoking. But ultimately, I agree with his conclusions and don’t know if I have anything significant to add. So I thought I’d bring back an article from a couple years ago (with appropriate editorial revisions) that also addresses Christian influence on culture.

In today’s culture being offensive seems to be cause for intolerance.

A number of years ago I read a portion of an address the former provost of Stanford University delivered to the board of trustees of that school. In it, he decried the trend toward intolerance in an academic environment. I found the article because one of my Facebook friends posted a response published in Slate.

If you are unfamiliar with Slate, here’s the Wikepedia description:

Slate is an online liberal / progressive magazine that covers current affairs, politics and culture in the United States. . . It has a generally liberal editorial stance.

Given that piece of information, it’s clear what angle the article took in responding to the charge that academic institutions, Stanford University specifically, have become too intolerant. The Slate article, in fact, is titled “In Praise Of Intolerance.”

Yes, you read that correctly: intolerance. The goal, according to Alan Levinovitz, the author of the article, is truth. To make the point, he references hatred and the Holocaust, then says this:

Likewise, biologists reject creationism not because it is intolerant of evolution, but because it is wrong. The same is true when immunologists reject vaccine skepticism. White supremacists, creationists, and vaccine skeptics refer to their exclusion from higher education and mainstream media as a form of intolerance. And theyâre right—academic institutions are intolerant of their views. Yet we can all agree that Stanford neednât change its hiring practices. Those who strive to stamp out these dangerous views are intolerant, but justly so. (from “In Praise Of Intolerance”—Emphasis mine).

So, creationism, according to Mr. Levinovitz, is an intolerant view. An offense, you might say. Because the charge in these institutions of higher education is along these lines: students are offended when a Christian organization like Interversity, requires those in student leadership to be Christians. Because, you see, requiring Christian organizations to be run by Christians is apparently discriminatory.

Christian student groups have been allowed back onto University of California campuses, but new legislation in the state government came up some time later affecting private colleges and universities in the area of transgender issues. The bill was withdrawn, but the point is clear: as a culture, we are, in the name of tolerance, moving more and more toward intolerance.

Ironically, the U. S. Constitution, the document considered to be the Law of the land, contains an amendment insuring that those of us who hold opinions others find intolerant or offensive, still have a right to speak.

But Mr. Levinovitz would seem to take the view that those holding “wrong ideas” ought not be allowed to publish them or to voice them in a public place like a university campus.

The longtime best-selling book of Christian apologetics—C.S. Lewisâ Mere Christianity—calls for religious nationalism (âall economists and statesmen should be Christiansâ) and argues that God wants men to be the head of the household. These are popular ideals, but they are poisonous and deserve fierce resistance, not complacent tolerance. (Ibid.)

So apparently, the ideas C. S. Lewis supposedly espoused (because much of what the author claims, was taken out of context) ought not be tolerated. The implication is that Lewis and his books ought not be tolerated.

So apparently, the ideas C. S. Lewis supposedly espoused (because much of what the author claims, was taken out of context) ought not be tolerated. The implication is that Lewis and his books ought not be tolerated.

Was Lewis giving offense? Or are those who disagree with him simply offended because they find his conclusions in contradiction to their own?

The question is, how soon will Lewis be ousted from university bookstores? Will students be able to find copies of the Narnia books or his space trilogy in their libraries? Or in any library, if Mr. Levinovitz’s ideas about intolerance become widely accepted?

And what about the books of today. Should writers strap on the veneer of the tolerant in order to have a chance to be published in the general market? Just recently I heard about a wonderful manuscript that speaks to some of our western society’s raw wounds regarding racism. Can that story break through the barriers of traditional publishing? Unlikely, given the sensitivity with which publishers approach such books.

Christian publishers have their sensitivities, too. They want clean fiction, stories that are not negative toward Christianity, that have an element of faith. These publishers would perhaps be seen as intolerant of stories that contain scenes of promiscuity and language laced with profanity.

Ought general market publishers have tolerance toward, say, transgender issues, but not toward pro-life issues? I suppose those that own those publishing companies can choose which ideas to support and which to label as an offense.

The real question is this: are Christians ready to be marginalized further? Are we preparing to share the gospel regardless of how offensive the culture finds it or how offended people claim to be?

I’ve long said that Christians are not to be offensive in the way we speak, but the Bible itself says the message of the gospel is offensive to those who are perishing. To tell people they are sinners, is offensive. To say that some are saved and some are not, is to appear in the eyes of our culture to be discriminatory. To be hateful. To hold a position that ought not to be tolerated.

I’ve long said that Christians are not to be offensive in the way we speak, but the Bible itself says the message of the gospel is offensive to those who are perishing. To tell people they are sinners, is offensive. To say that some are saved and some are not, is to appear in the eyes of our culture to be discriminatory. To be hateful. To hold a position that ought not to be tolerated.

The point is, the more Christians withdraw from the culture, the more we fail to engage the offensive questions publicly, the less likely we will be to do so at all in another twenty years.

Are we to outshout those who say the kinds of things Mr. Levinovitz said—that creationism is wrong and not to be tolerated? That’s not the most effective approach, I don’t think, and it’s not the one the Bible endorses.

We are to make disciples, Jesus said before He left earth. We are to go into all the world and preach the gospel. But we are also to live as salt and light.

So I wonder, are Christian novels today shining light? Yes, I realize we, the actual, physical people who follow Christ, are to be salt and light. But how do we show our light if not by what we do and say and think and write? How do we influence and affect the culture around us, giving flavor and providing the preservative power of the gospel, if not by our stories?

The question, in the end, is this: are we an offense to those around us or are they responding to the truth of God’s word (either positively or negatively), lived out in what we Christians do and say and write?

Post Script: I’m adding this video that I just say (a little over 5 minutes long) which also addresses these same issues:

Iâm in good company when it comes to rejections. I weathered that storm while searching for a publisher for the Tales of Faeraven series. It was hard to ignore the warning bandied about in literary circles: âChristian fantasy is a hard sell.â Knowing when to heed the collective wisdom and when to ignore it is a matter for prayer. I wonât say that I didnât question my course or wish for an easier path, but I couldnât ignore the unction to find a publisher for Tales of Faeraven.

Iâm in good company when it comes to rejections. I weathered that storm while searching for a publisher for the Tales of Faeraven series. It was hard to ignore the warning bandied about in literary circles: âChristian fantasy is a hard sell.â Knowing when to heed the collective wisdom and when to ignore it is a matter for prayer. I wonât say that I didnât question my course or wish for an easier path, but I couldnât ignore the unction to find a publisher for Tales of Faeraven. Janalyn Voigt is a multi-genre novelist who has books available in the western historical romance and epic fantasy genres. Her unique blend of adventure, romance, suspense, and whimsy creates worlds of beauty and danger for readers. An inspirational, motivational, and practical speaker, Janalyn has presented at the Northwest Christian Writersâ Renewal Conference and Inland Northwest Christian Writers Conference. She has also spoken for local writing groups, book events, and libraries. Janalyn is represented by Wordserve Literary and holds memberships in American Christian Fiction Writers and Northwest Christian Writers Association.

Janalyn Voigt is a multi-genre novelist who has books available in the western historical romance and epic fantasy genres. Her unique blend of adventure, romance, suspense, and whimsy creates worlds of beauty and danger for readers. An inspirational, motivational, and practical speaker, Janalyn has presented at the Northwest Christian Writersâ Renewal Conference and Inland Northwest Christian Writers Conference. She has also spoken for local writing groups, book events, and libraries. Janalyn is represented by Wordserve Literary and holds memberships in American Christian Fiction Writers and Northwest Christian Writers Association.

2019 ACFW Carol Award for best young adult novel

2019 ACFW Carol Award for best young adult novel 2019 ACFW Carol Award for best speculative novel

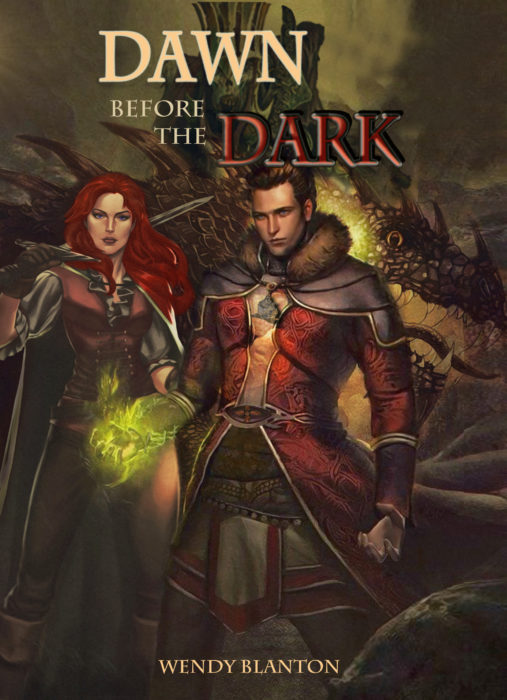

2019 ACFW Carol Award for best speculative novel 2019 ACFW Carol Award for best debut novel

2019 ACFW Carol Award for best debut novel

I love the “how did that happen” stories, which I think are seldom presented in the case of dystopian worlds. Those novels usually start with an overbearing totalitarian government in charge, controlling the populace and creating havoc with their policies. Consequently, I think Jill Williamson has a brilliant idea—go back and look at what happened that created the Safe Lands and the authoritarian world that was the basis for that series.

I love the “how did that happen” stories, which I think are seldom presented in the case of dystopian worlds. Those novels usually start with an overbearing totalitarian government in charge, controlling the populace and creating havoc with their policies. Consequently, I think Jill Williamson has a brilliant idea—go back and look at what happened that created the Safe Lands and the authoritarian world that was the basis for that series. BUT, Jill Williamson is promoting the new book, the prequel, THIRST, which launches November 21. I hardly have to point out that this date will allow you to purchase a copy for a Christmas gift for anyone you know who has a love for fantasy. Plus, Jill is making available some swag. You can think of this as her own book box, available on a limited basis. Here’s what she said in her newsletter:

BUT, Jill Williamson is promoting the new book, the prequel, THIRST, which launches November 21. I hardly have to point out that this date will allow you to purchase a copy for a Christmas gift for anyone you know who has a love for fantasy. Plus, Jill is making available some swag. You can think of this as her own book box, available on a limited basis. Here’s what she said in her newsletter: Hardcover:

Hardcover:

At least two of these books in this last category are speculative at some level, where as Matt Mikalatos’s novel is unashamedly a fantasy.

At least two of these books in this last category are speculative at some level, where as Matt Mikalatos’s novel is unashamedly a fantasy.

This at once makes me feel two emotions.

This at once makes me feel two emotions.

Mark Carver

Mark Carver  Finally there’s the issue of our guiding image for Heaven. Revelation 21 presents this image as a glorious golden city that “[comes] down out of heaven from God” (Revelation 21:2). Mark Carver

Finally there’s the issue of our guiding image for Heaven. Revelation 21 presents this image as a glorious golden city that “[comes] down out of heaven from God” (Revelation 21:2). Mark Carver