An entire book could be written on this topic (perhaps I’ll do that someday) but to keep this as brief as possible, the short reason this is a problem is the Bible has nothing good to say about the practice of magic (neither does extra-Biblical Christian tradition). No translation of Scripture will record the 12 Disciples watching Jesus walk on the water and say, “Wow, that was magical!” Nor is the mana falling from heaven in Israel’s wilderness wanderings described as some kind of powerful spell that Moses used, nor even is his rod described as “magic,” even though Moses had the power granted to him by God to turn it into a serpent at whatever time he chose. No, the Bible describes events like these as “miracles,” or “signs,” or “wonders.”

Supernatural power from God at the parting of the Red Sea. Image credit: Allcreatures.org

A verse in Isaiah (8:19) directly contrasts reliance on God with the use of magic: “When they say to you, ‘Consult the mediums and spiritists who whisper and mutter,’ should not a people consult their God? Should they consult the dead on the behalf of the living?” (That’s the NASB–the King James Version uses the word “wizards” instead of “spiritists.”) Note this verse is specifically talking about necromancy for the purpose of divination in context, but note that the Bible has many examples of non-divination magic, magic also not shown to be directly connected to raising up spirits. This passage points out the fundamental reason why seeking “magic” (as the Bible defines it) is wrong and the reason is not limited to necromancy–it’s wrong because it detracts from seeking God and his power.

Note that the passage in Deuteronomy 18 that E. Stephen Burnett made the focus of his comments (verses 10-11) says: “10 There shall not be found among you anyone who makes his son or his daughter pass through the fire, or one who practices witchcraft, or a soothsayer, or one who interprets omens, or a sorcerer, 11 or one who conjures spells, or a medium, or a spiritist, or one who calls up the dead.” The very first thing this passage references is a Canaanite practice of offering an infant to their gods in an attempt to manipulate their favor–that is, the very first act condemned along with a list of magical practices is actually something the Canaanites would have defined as an act of worship to their gods. This why “seeking supernatural power from sources other than God” is the glue that binds this passage together and which applies to all the specific practices it lists. Yes, at the time of writing of that passage, divination was probably the most common practice of those who sought to work “magic”–but it was by no means the only one. It was not even the first or most important one in this particular passage and as I’ve already shared, magic refers to many other things that have no connection to divination in the Bible, including manipulation of forces of nature by Pharaoh’s men, which looks pretty much like magic in many fantasy stories.

“So why bother putting magic in stories at all?” someone might ask. “If magic can be an issue, why shouldn’t a Christian writer leave it out of stories altogether?” I’d say there are three basic reasons to work out a means to include magic in stories: 1) Fantasy is a popular genre with loads of readers. It makes sense to desire to reach them within their genre expectations from a strictly analytical point of view. Not to mention it can inherently interesting to write fantasy for people who’ve read it–and fantasy normally contains magic. 2) Fantasy has the ability to use analogy or allegory or myth-making to create powerful messages about the world we live in. And what the story calls “magic” can be a key part of any such analogy. C.S. Lewis achieved using the word “magic” that way in the Chronicles of Narnia, in fact. 3) And it so happens to be that magic is a staple of fantasy as much as aliens are a staple of science fiction. You could write the one without including the other, but it would not really represent the genre well for the most part. Or be as interesting.

So, how to proceed? I would say the basic task is to make it plain the magic in the story world is not the same thing as the sorcery the Bible condemns. In order to harmonize with the Bible’s condemnation, a Christian writer must make it plain that the supernatural power referenced in the story is not in fact in opposition to reliance on the Creator God of the Bible. I know of six good ways to do this (and will reference a seventh way):

1. Only the villains have “magic.”Â

This is probably the most straightforward approach. Bad guys use spells, sorcery, incantations, and magic items. Good guys are stuck with either plain items devoid of any magical powers, or have supernatural power openly linked to God and under His control rather than theirs (and which is never described by the term “magic”). The Left Behind series actually shows baddies into witchcraft whereas the good guys, especially the two prophets in Jerusalem, call down supernatural power overtly in the name of God. To take this notion into the realm of fantasy, take this same sort of thing but instead of setting it on Planet Earth, put it in a world of imagination, but one where God is still God, though perhaps under a different name (e.g. Aslan–though note that magic in Narnia is not just reserved for the villains).

2. Rename miracles and prophets as “magic” and “wizards.”

Take a person who acts like a prophet of the Old Testament, but call him or her something other than “prophet.” Create situations similar to Moses parting the Red Sea or Elijah lighting the sacrifice to God with fire from heaven, but don’t call it prophecy or a miracle or a sign or a wonder. Call it “magic” or “sorcery” instead and those who them “wizards” who call upon the equivalent of the name of God in the story. By linking the activity you’re calling “magic” clearly to the Creator God in the story, you’re making it plain that you’ve simply changed the functional definition of “magic” within the context of your story world. Doing this would take advantage of the fact that fantasy readers expect magic in a tale, but turns their expectation on its head so the story magic works the opposite from how the Bible negatively uses the word. Therefore, done correctly, such wizards would really point back to prophets and their sorcery powers back to God’s power (by whatever name He is presented in the story). Readers who are not Bible-savvy may not immediately notice that the story points back to a Biblical way of seeing the supernatural, even though that’s what it would do. By the way, L. B. Graham, Christian author of fantasy, has used this approach in some of his books.

3. Treat “magic” as an allegory for the workings of God.

I’m thinking especially of how C.S. Lewis used the term “Deep Magic” as a description of what the “Emperor-beyond-the-sea” had written in the stone table where Aslan was sacrificed (in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe). It stated that the White Witch was entitled to kill every traitor and if anyone denied her that right, then all of Narnia would perish in fire and water. But an even deeper magic said that if a willing innocent victim was killed in the place of a traitor, then the Stone Table would crack and death would be overcome. Clearly this references how Christians see Christ dying on the cross for sin, but is phrased as “magic.” A story could call other acts of God or properties of God that parallel what we know to be true, “magic.” Wizardry of this sort would not in fact allow characters to use spells (because “magic” is part of the structure of the universe) and as such might call for the addition of another method of dealing with “sorcery” (one that does allow spells). Though I can imagine a fantasy story without spells at all in which all references to “magic” are simply to acts of God in allegorical form.

4. Treat magic as a form of undiscovered science.

I have imagined in stories I’ve written that magic is a kind of physics that operates in other universes but which is undetectable here. I conceived of magic as a form of power that flows though the multiverse not unlike how electricity flows through a circuit. For universes closest to the source, this power is readily available. The power is subject to manipulation by acts of the will and spoken words (so the use of this power resembles spells), but other universes drain most of the power by the time it hits our universe, so it has never been discovered in our world. In universes that have active magic, wizards are like scientists who study the properties of the invisible and learn how to use it, like how scientists learn to manipulate the forms of energy and matter we know about. Like science, such power can be used for either good or evil and like technology, there are unexpected residual wastes that can be harmful.Â

Other novelists have invented other means in which “magic” is either science by another name (as I’ve done myself in the “Time of Magic” referenced in Medieval Mars) or have stated magic is an undiscovered science. Note that making sorcery equal science may create a story universe very similar to ones written from a non-Christian perspective, of the sort that have wizards and spells. But the difference is the kind of story that creates magical power which can be used in a neutral sense isn’t really supernatural power anymore. It’s the power derived from the ordinary physical world as much as photography, internal combustion engines, and atomic power is. What is called “magic” really should be considered part of the natural order in such stories.

It still would be possible for a character to seek supernatural power in an illicit way in such a story world by knowingly circumventing whatever understanding of God he or she had, which would amount to the sin of witchcraft, i.e. trying gain supernatural power without God. Which in that story universe would be a separate thing from the use of magic as in science by another name or in another form.

5. Blend the lines between the supernatural and natural into a strange universe.

What I just suggested in effect blends the supernatural and natural by making acts that would appear to be supernatural merely natural acts, merely the acts of a type of science instead. But I’m suggesting here goes the opposite way.Â

A recent example of a Christian writer using “strange universe magic.” Image copyright: C.E. White

Instead of giving everything a natural explanation, nothing has one. Everything is off-the-rails strange and nothing can be said to be a deliberate attempt to achieve the supernatural without God because everything (or most everything) is already supernatural from the point of view of planet Earth as we know it. I’m thinking of Alice in Wonderland or The Wizard of Oz type story universes, where scarecrows and rabbits talk, where changing your size is a matter of what you eat and drink, and tornadoes will transport a house to another land without killing its occupants.In this kind of strange universe, magic is so worked into the fabric of everything that it isn’t special and using it is as natural as walking and breathing. Then that sort of magic does not relate to the Biblical condemnation of people seeking the supernatural without God. Though such a story can shut out God by never mentioning Him and can act as a sort of allegory for witchcraft, it certainly does not have to be. A story universe like this can just as soon mention God in various ways, even though the classic examples I mentioned do not.

6. Treat magic as an innate special ability in analogy to spiritual gifts.

This approach in some ways is a subset of #5, but can also employ notions of #4 as well. It might seem logically contradictory for a story to be both more and less scientific in its approach to the supernatural at the same time, but the author I know who uses this method makes both work. Kat Heckenbach starting in Finding Angel treats the power of magic as a gift that an individual has, given from beyond herself or himself. As such, her approach runs parallel to what the Bible has to say about spiritual gifts, almost forming an allegory of them. Yet since working the supernatural is just a natural ability, she in effect makes the supernatural more common and ordinary as per point #5. But at times she gives specific descriptions of how someone’s ability affects matter or energy in terms someone who has studied science on planet Earth would recognize. Which goes back to #4. In truth, Kat’s approach is unique, but her basic idea of making magic an inherent gift the magic user possesses can well harmonize with a worldview that does not include witchcraft in the Biblical sense of the term.

Dragging magic God condemns into an examination of God’s gifts. Image credit: ohippo.com

Note though that Pagans too have imagined that someone could be born with an innate ability to perform magic that does not really require casting of spells in the ordinary sense. Obviously, if they link such an inherent ability to their gods and goddesses, this would be a portrayal of magic the Bible would condemn. (It’s even possible to corrupt this idea in other ways, as to imagine Christians should be using astrology, tarot, ouija, or other forms of divination the Bible would condemn to find out their “spiritual gift from God”.)

7. Downplay the Biblical objection in the first place.

This approach seventh would be to either ignore altogether what the Bible says about magic or claim it only references a specific kind of attempt to gain supernatural power without God. I have heard people use the verse I quoted in Isaiah to claim the Bible does not condemn all magic, it only condemned necromancy, that is, trying to interact with or raise the dead. Or as I mentioned, some claim that Deuteronomy 18 only references divination or the point of Isaiah 8 amounts to divination as well. So as long as you stay away from these specific kinds of magic, the thinking goes, you’re clear. Which is why I gave examples outside of Isaiah and Deuteronomy. In fact, the Bible condemns far more that just necromancy and divination. It takes a broad shot at seeking supernatural power apart from God as a whole, though we need to understand by study what that really means.

I don’t recommend approach #7. I think one of the things that distinguishes an overtly Christian writer of speculative fiction is the attempt to work these issues out by some means or other. Not to ignore them. It does not mean conformity to just one way of thinking and it doesn’t mean it’s impossible to be creative or imaginative. (Kat certainly was creative in her solution.)

The value of the entertainment factor is apparent simply by looking at how many people attend or watch football on any given weekend, versus the number of people who visited a local museum. Or perhaps, church.

The value of the entertainment factor is apparent simply by looking at how many people attend or watch football on any given weekend, versus the number of people who visited a local museum. Or perhaps, church. Nevertheless, a number retained the goal to pass along values to the next generation. Consequently Pilgrim’s Progress became popular, but so did stories by Charles Dickens and even a children’s series about

Nevertheless, a number retained the goal to pass along values to the next generation. Consequently Pilgrim’s Progress became popular, but so did stories by Charles Dickens and even a children’s series about

And so, as I build these improved editions of my backlist and forge onward to writing new novels, I walk a hazy line in the realm of themes. I must tread carefully between offering the theme of hope: âYouâre not stuck. Small steps in the right direction are valid. And God can use you even if youâre a serious work-in-progressâ and indulging my characters some easy preaching. Itâs nervous work to weave inspiring character transformation into an engaging story, especially when an author canât control whether readers who catch a whiff of a Judeo-Christian worldview in a book will sound the Preach Alarm.

And so, as I build these improved editions of my backlist and forge onward to writing new novels, I walk a hazy line in the realm of themes. I must tread carefully between offering the theme of hope: âYouâre not stuck. Small steps in the right direction are valid. And God can use you even if youâre a serious work-in-progressâ and indulging my characters some easy preaching. Itâs nervous work to weave inspiring character transformation into an engaging story, especially when an author canât control whether readers who catch a whiff of a Judeo-Christian worldview in a book will sound the Preach Alarm.

Friday, in response to our Spec Faith

Friday, in response to our Spec Faith  A number of years ago Peace Like A River by Leif Enger made a great splash (no pun here), even winning awards and reaching best-selling status. To be honest with you, I didn’t like the book. At all. It had some good features, truly, but that didn’t change the fact that I didn’t like it. Yet I have to say, it made me think. I couldn’t walk away without wrestling a bit with a theme of the book: does God involve Himself in the personal and specific affairs of men?

A number of years ago Peace Like A River by Leif Enger made a great splash (no pun here), even winning awards and reaching best-selling status. To be honest with you, I didn’t like the book. At all. It had some good features, truly, but that didn’t change the fact that I didn’t like it. Yet I have to say, it made me think. I couldn’t walk away without wrestling a bit with a theme of the book: does God involve Himself in the personal and specific affairs of men?

Mind you, I never wrote, âRain will forgive this personâ or âThis is the scene where so-and-so forgives Rainâ while I was plotting Stormrise. Rather, the forgiveness expressed in these scenes is a natural outgrowth of the character arcs, according to my views on forgiveness. In each instance, a character can choose whether to forgive or not. And I believe choosing forgiveness is the stronger (though not necessarily the likely) path.

Mind you, I never wrote, âRain will forgive this personâ or âThis is the scene where so-and-so forgives Rainâ while I was plotting Stormrise. Rather, the forgiveness expressed in these scenes is a natural outgrowth of the character arcs, according to my views on forgiveness. In each instance, a character can choose whether to forgive or not. And I believe choosing forgiveness is the stronger (though not necessarily the likely) path. BIO—

BIO—

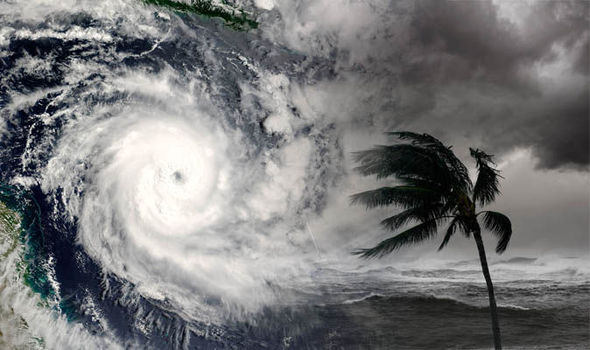

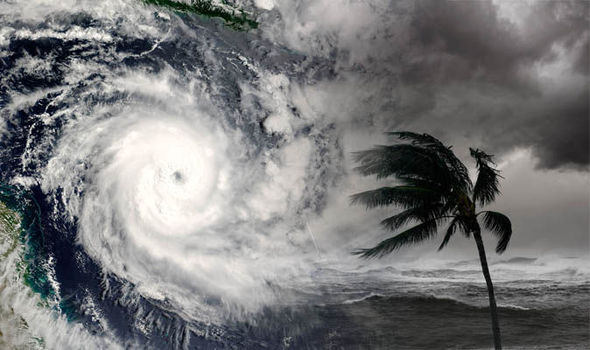

If you’ve been paying attention the 24-hour news cycle, you might get the idea that humanity is to blame for any natural upheavals, especially as it relates to the weather. The talking heads ponder how industrialization directly correlates to strong storms such as Dorian. The world’s average temperature has increased over the last several decades and the debate remains about the causes and effects. There is no question that we should take care of the world as its stewards (Gen. 1:28) but the ideological battle rages on about whether we are responsible for the turmoil we see around us.

If you’ve been paying attention the 24-hour news cycle, you might get the idea that humanity is to blame for any natural upheavals, especially as it relates to the weather. The talking heads ponder how industrialization directly correlates to strong storms such as Dorian. The world’s average temperature has increased over the last several decades and the debate remains about the causes and effects. There is no question that we should take care of the world as its stewards (Gen. 1:28) but the ideological battle rages on about whether we are responsible for the turmoil we see around us.