I spent the past six days involved in a story-term mission ministry called “No Greater Love” in which men from a variety of places go to New Orleans during Mardi Gras to pass out Gospel tracts and other means of overt and not-as-overt methods of evangelization, including marching down Bourbon Street while carrying a cross in order to symbolize Christ to a generally very hostile party crowd. The trip provided me copious illustrations to talk about spiritual warfare, but for this article I’m going to keep it briefer than I otherwise would (I just got back last night) and will focus on just one aspect of things I observed for the moment. That is, in mingling with Christians from other churches, I met a lot of very sincere and nice believers who believe some rather odd things. Things I’m going to call here spiritual placebos.

Since these practices relate to things Christians do in the real world, they also relate to how Christians might be portrayed in stories. This topic also potentially relates to how spiritual warfare could be depicted in stories.

The placebo effect, for the few readers here who may not be completely familiar with it, refers to treatments with no real medical effectiveness that are generally presented to the patient as having an effect and the simple thought the placebo could help really does in fact help patients to a degree, though not as much as actual medicine (note there have been some studies where patients were told they were receiving placebos and the effect seemed to have happened anyway, for more info reference footnote eight of the linked Wikipedia article on “Placebo”). In fact, medicines are routinely tested against placebos such as sugar pills. If the medication is not more effective than a sugar pill, it doesn’t get official approval–though some medicines that win approval have effects only very slightly better than placebos (anti-depressants in general are only a bit better than placebos).

Placebos Are Not Harmful–But Not Real Medicine, Either

I’m making the somewhat controversial claim that for some Christians, certain spiritual practices act like placebos. I recognize I’m treading on dangerous ground a bit. Critics of Christianity will claim all results that stem from faith come from the placebo effect–it’s all in all in our heads, none of it is real. I certainly don’t want to give them ammunition against all faith. Nor do I mean to say the practices I’m going to talk about are actively evil or from the Devil or something. Though I do think harm can come if people expect more from these practices than they should.

If I don’t think these practices are actually bad, why bring them up? Why not let Christians continue in them if they aren’t harmful? I do have a specific reason for the approach I’m taking. I hope explaining these practices and what the Bible says about them will help Christians grow in maturity and understanding, and in the long run, make them better Christians.

A Scriptural Bias Towards Epistles

I’ve said this before for a different article, but to re-phrase here, I think a proper understanding of the Scriptures divides it into groups of texts. Books that relate history of the Bible show us events that did actually happen, so the miracles they at times reference clearly could happen again. God’s ability to perform miracles certainly has not been reduced over time–though not all periods of history had an equal amount of miracles or direct revelations from God. Some periods had very few (see I Samuel 3:1), others had more. It seems God worked as the situation required or perhaps as a situation allowed.

But as a Christian I know I can learn more about how a Christian should act based on the part of the Bible that is written to Christians, as opposed to parts written for ancient Israelite priests or kings. Which means the epistles more than anything else because apostles wrote them for the direct purpose of providing instructions to churches. The practices of Christian churches should therefore be derived from epistles, though of course informed by the Gospels and history of the Bible and everything else the Bible has to say. But again: the epistles contain the marching orders for the church–that’s their purpose.

So I call something a “placebo” if it’s a Christian practice people believe in that isn’t ever commanded in any epistle. If it’s something people do that the Bible never tells us to do. Which isn’t quite the same as me saying it has no effect at all.

Note I adopt this attitude not based on skepticism per se, but on on a belief in study and that our minds are given to us by God for a good purpose. That yes, while we should be guided by the Holy Spirit, we should also be guided by Scripture and that the Scripture is something we can understand with our minds and apply as we need to. And if the Bible doesn’t tell us to do something in clear terms, the practice of doing it at the very least is doubtful–though it may in fact be wrong or even harmful in some cases.

The Bible tells us to pray. So we ought to pray. It also mentions music and congregational worship and Communion and even miraculous gifts. Among many other things. But there are other things it never says we ought to do. Such as:

Anointing Oil

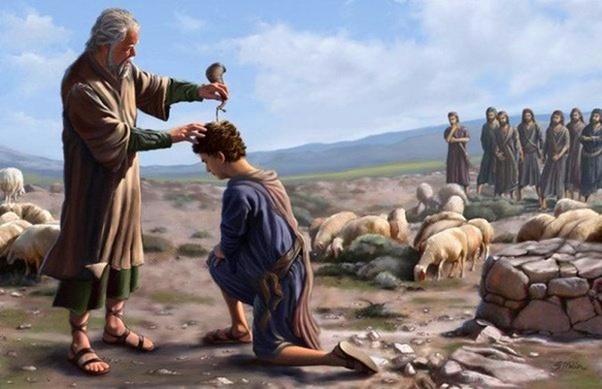

The use of oil in the Bible has symbolic meaning of blessing and special appointment. All priests had oil poured on them as part of their appointment to the ministry and at times kings were anointed, as was a prophet anointed at least once in the case of Elijah anointing Elisha. Oil was also used in the temple service as part of the offering system including in ceremonial cleansing (please pardon the lack of Scriptural references at the moment).

Oil was so important in Biblical culture that one who received the oil was seen as especially blessed to the degree that “Messiah” means “one anointed with oil” and “Christ” is based on the Greek word meaning the same thing. Jesus is the one especially anointed–that’s how important the act of pouring oil on someone is in the culture and history of the Bible.

Samuel anointing David as future king of Israel. Image source: Quora

However, is anointing with oil ever commanded in the epistles? Yes, once, in James 5:14, in which it’s associated with what the elders of a church should do for someone sick and needing healing. This one passage has been looked at in many different ways and I’m not going to wade into the details at the moment to say which view is right. But let’s note there are no other commands to use anointing oil in the epistles.

So when I met a man, quite a nice person, who said he’d asked his pastor to anoint him with oil before coming to the mission trip with No Greater Love because, “Anointing is powerful,” I didn’t say anything. He was entitled to ask for that if he wanted. It would have been especially appropriate if he saw it as a sign of the pastor appointing him to a special ministry because that would echo a lot of Old Testament history. But it seemed the man felt the oil itself was somehow special. And I’d say it wasn’t or we’d be clearly told to use it in a Biblical epistle in all such cases.

Another very nice man, along the same lines, said all of us who came for the trip need to be anointed with oil so we could get the power of God for what we were doing. The leaders of the camp didn’t take time out for all of us to do that, but it was interesting the idea that the man expressed there. He wanted anointing, not because any of us were sick, but as a means of empowerment. But anointing oil for power is not only not mentioned in the epistles, it’s not mentioned in Acts, either. A book with plenty of examples of God working in powerful ways.

I think it’s safe to say thinking of anointing or anointing oil as especially powerful is a spiritual placebo. Not harmful except if you rely on it too much, but not helpful in and of itself either.

Plead the Blood of Jesus

Yes, the blood of Jesus is powerful according to Scripture (re: verses like Romans 5:9). But does anyone in the Bible actually say “I plead the blood of Jesus” in a prayer? Nope. Not once. And no epistle commands believers to pray that way.

Yet there are Christians who pray that phrase as if doing so makes the prayer extra-powerful. Does it? Well, if a person believes the phrase is important I can imagine God honoring its use–God is merciful like that. But God never commanded it or ordered it. Any effect the phrase has therefore must be something rather similar to a placebo. Maybe it makes some people feel better, but the actual effect as in moving God more than praying without the phrase is nil.

Where the Sole of Your Foot Treads

There are people who take the example of Joshua, in which God tells him wherever he walks he would conquer as a prescription for how Christians should pray (Joshua 1:3). Specifically for the ministry I was involved in, there were men who walked down Bourbon Street in the morning and prayed over the ground they walked on. Which is fine. There’s no harm in praying over what will happen on every single bit of a piece of terrain. But some people phrased their action a bit differently: that they were claiming the territory for Jesus and marking the place they walked as holy ground.

If that were something that’s important, Paul or another apostle would have laid it out in an epistle. Something like, “Walk the streets of places you proclaim the Good News to claim them for the Lord and pray without ceasing as you do so.” But that’s not there. Nor is there an example even of Paul or any other apostle walking all the streets of, say, Ephesus, to claim them for the Lord. Hey, not even Joshua walked all the streets of the cities he conquered according to what the Bible plainly states. He simply went from one city to another and his men went through all the streets.

So if you want to walk down a street with the thought that you want God to do great things there, by all means, think and pray that. But your feet hitting the ground is not some special act. You are not Joshua and if God had meant for it to be super-important for us to walk around places to claim them, God would have told us in plain terms to do so. Because God is pretty straightforward with telling us the things we really need to know!

Addressing the Devil in Prayer

Some Christians I rubbed shoulders with informed the Devil as they were praying that he was bound, that he was under the blood of Jesus that he had no more power anymore.

OK, well, we know Jesus talked to Satan when He was tempted and addressed demons when commanding them out of people. But are we ever told to address the Devil in prayer? Nope. Philippians 4;6 and lots of other places tell us to pray to God, but never gives us instructions on how to talk to the Devil.

Passages on facing attacks from Satan, of which there are a number of clear examples (e.g. I Peter 5:7-8) never mention talking to the Devil or the need to directly “bind him” with our words. Look folks, God is good and will give us what we need to know. If we needed to talk to Satan, he’d tell us. But he didn’t.

Is it harmful to address Satan directly? If your faith is in God and you submit to the Lord, God’s power will make Satan flee. So you can mention Satan in prayer but at the moment be thinking of what God will do to him. So God can honor that.

But if you’re thinking you have the power to drive away Satan based on your own merit–well, I’d call that “no bueno.” But I think people who pray that way would agree that you have to know the power comes from God.

So why pray that way at all? It isn’t especially powerful or God would have told us to do it.

Binding Sickness

As mentioned in the previous section, prayers that mention the Devil that I heard also tended to say that he was “bound” or claimed the power to “bind” Satan. That’s based on Matthew 12:29 in which Jesus stated a strong man has to be bound (tied up) before you can steal his goods as a way of explaining his power over Satan to cast out demons. By the way, I have no problem with calling on God to bind Satan as in reduce his power. That makes sense–even if directly addressing the Devil to inform him he’s bound isn’t something the Bible tells us to do.

But how about binding illness? Doesn’t that imply illness is like a demon, that it has will and can act on its own? That maybe illness actually is a demon? That by binding it you claim some kind of special power over sickness?

The Bible references multiple reasons for illness that I won’t spell out here but never states that every illness comes directly from Satan. In fact, John 11:4 and some other passages state that a particular illness happened for “the Glory of God”–not because Satan wanted it to.

And back to the epistles–do we see examples of illness being bound or a command given to bind illnesses? Nope. None.

Can God understand that you really mean healing when you talk about binding sickness? Sure. But why not simply pray it the way that makes sense–“God, please heal” instead of “in the name of Jesus I bind this sickness”? The latter is supposed to be more powerful, but it isn’t. At most, it can make people feel better. Like a placebo.

Conclusion

Again, I don’t mean to say these practices are of the Devil or that they necessarily are harmful. But why wander into doing things that God never commanded Christians to do? Isn’t what we’ve clearly been told to do good enough?

Readers, I recognize the tone of this article could be seen as especially critical of my fellow believers in Christ. I don’t mean to be–but I do mean to suggest people ought to trust the Bible and what it says more and the practices they’ve observed among other Christians less, especially those things not spelled out in Scripture.

I also don’t mean to make people feel picked on here. There is freedom in Christ to do specific things God has never commanded anyone to do if you feel so led as long as those things aren’t specifically sinful. The problem is if you feel that people who don’t practice the same way as you must be in the wrong. As in, “this guy never pleads the blood of Jesus, so his prayers must be worthless.”

I hope this makes sense and is helpful. May God bless you as you read.

By Mirtika Schultz

By Mirtika Schultz

I’ve actually met Kara, even worked on the SoCal Christian Writing Conference with her for a couple years. Further, I did a little editing for her a year or so ago. I can say, she is a remarkable young writer, a hard worker, willing to help others, and excited about speculative fiction. She’s a member of a number of Facebook speculative writing communities, including

I’ve actually met Kara, even worked on the SoCal Christian Writing Conference with her for a couple years. Further, I did a little editing for her a year or so ago. I can say, she is a remarkable young writer, a hard worker, willing to help others, and excited about speculative fiction. She’s a member of a number of Facebook speculative writing communities, including  The truth about Neverland is far more dangerous than a fairy tale.

The truth about Neverland is far more dangerous than a fairy tale.

Shouldn’t there be statues to great men? Or museums? Or, at least, oral traditions telling of the history of the world?

Shouldn’t there be statues to great men? Or museums? Or, at least, oral traditions telling of the history of the world?